Dance and Modernization in Late Twentieth Century Montreal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opening Remarks

Opening Remarks Lawrence Adams was Amy Bowring’s revered mentor; his example has guided and encouraged her to tackle, with determination and purpose, assorted pursuits in dance. As Research Co-ordinator at Dance Collection Danse, Amy has been working with the organization, on contract, for five years. Many of you may know Amy through some of the projects in which she has been involved, and also as founder of the Society for Canadian Dance Studies which can boast a solid and active membership under her direction. First introduced to Dance Collection Danse in 1993 as a student undertaking research through York University’s dance programme, Amy’s passion for dance history triggered her interest in becoming seriously involved with DCD. After completing her BA in Fine Arts, Amy earned an MA in journalism from the University of Western Ontario. She is copy editor for The Dance Current magazine, has written various dance articles and encyclo- pedia entries, and is researching and writing a book on the 1948-1954 Canadian Ballet Festival phenomenon. And, to add more ingredients to the mix, she is a whiz at the computer! As Dance Collection Danse undergoes its planning process for upcoming and future activities, you can expect to see Amy’s involvement with DCD increase. To work with someone who is dedicated and skilled is a blessing, but to have someone on board who is also mindful and gracious is the best. The Editoral Committee and Board of Directors of Dance Collection Danse have dedicated this issue to Lawrence Adams, whose contribution to Canadian dance makes him deserving of .. -

Rapport Annuel 18/19

RAPPORT ANNUEL 2018-2019 SOMMAIRE TABLE OF CONTENTS LES GRANDS BALLETS 4 LES GRANDS BALLETS MOT DU PRÉSIDENT 6 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT HISTORIQUE DES GRANDS BALLETS 8 HISTORY OF LES GRANDS BALLETS LES GRANDS BALLETS EN CHIFFRES 12 LES GRANDS BALLETS AT A GLANCE SAISON 2018-2019 16 2018-2019 SEASON MUSIQUE ET CHANT 18 MUSIC AND SONG LE BALLET NATIONAL DE POLOGNE 21 THE POLISH NATIONAL BALLET RAYONNEMENT INTERNATIONAL 23 INTERNATIONAL CELEBRITY LA FAMILLE CASSE-NOISETTE 26 THE NUTCRACKER FAMILY CENTRE NATIONAL DE DANSE-THÉRAPIE 28 NATIONAL CENTRE FOR DANCE THERAPY LES STUDIOS 30 GALA-BÉNÉFICE 2018 35 2018 ANNUAL BENEFIT GALA LES JEUNES GOUVERNEURS 36 THE JEUNES GOUVERNEURS COMMANDITAIRES ET PARTENAIRES 38 SPONSORS AND PARTNERS REMERCIEMENTS 39 SPECIAL THANKS Photo: Sasha Onyshchenko • Danseuse / Dancer: Maude Sabourin DANSEURS 45 DANCERS 3 LES GRANDS BALLETS FAIRE BOUGER LE MONDE. AUTREMENT. Depuis plus de 60 ans, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens de Montréal sont une compagnie de création, de production et de diffusion internationale qui se consacre au développement de la danse sous toutes ses formes, en s’appuyant sur la discipline du ballet classique. Les danseuses et danseurs des Grands Ballets, sous la direction artistique d’Ivan Cavallari, interprètent des chorégraphies de créateurs de référence et d’avant-garde. Les Grands Ballets, reconnus pour leur excellence, leur créativité et leur audace, sont pleinement engagés au sein de la collectivité et rayonnent sur toutes les scènes du monde. MOVING THE WORLD. DIFFERENTLY. For over 60 years, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens de Montréal has been a creation, production and international performance company devoted to the development of dance in all its forms, while always staying faithful to the spirit of classical ballet. -

Un Studio En L'honneur De Fernand Nault

Communiqué de presse Pour diffusion immédiate Un studio en l’honneur de Fernand Nault Montréal, le 13 février 2012 — L’École supérieure de ballet du Québec salue l’héritage de Fernand Nault, pionnier de la danse au Québec, et rebaptisera un studio de danse en son honneur le 13 mars prochain. Celui qui a chorégraphié le fameux Casse-Noisette que présentent les Grands Ballets Canadiens à l’approche de Noël, tous les ans depuis 1964, a travaillé avec plusieurs générations de danseurs. Il a également fait sa marque à l’École supérieure, où il a notamment été directeur de 1974 à 1976. « J’ai eu la chance de côtoyer cet artiste généreux, d’une grande ouverture, raconte Anik Bissonnette, maintenant directrice artistique de l’École supérieure de ballet du Québec. Lorsque je reprenais un rôle dans l’un de ses ballets, il me donnait l’impression qu’il le créait de nouveau, spécialement pour moi. » Le studio Fernand-Nault sera décoré avec des photographies d’archives retraçant le parcours du danseur, du maître de ballet et du chorégraphe qu’il a été. « Nous souhaitons préserver le passé pour mieux construire l’avenir. Nous sommes persuadés que cette figure inspirante encouragera nos élèves à poursuivre leur rêve de devenir danseur professionnel », affirme Alix Laurent, directeur général de l’École supérieure de ballet du Québec. « Il a toujours traité les jeunes comme des danseurs professionnels, et je pense que c’est pour cela que les jeunes l’aimaient autant », dit André Laprise, fiduciaire du Fonds chorégraphique Fernand Nault, partenaire de cette commémoration. -

Dis/Counting Women: a Critical Feminist Analysis of Two Secondary Social Studies Textbooks

DIS/COUNTING WOMEN: A CRITICAL FEMINIST ANALYSIS OF TWO SECONDARY SOCIAL STUDIES TEXTBOOKS by JENNIFER TUPPER B.Ed., The University of Alberta, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF CURRICULUM STUDIES; FACULTY OF EDUCATION; SOCIAL STUDIES SPECIALIZATION We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 1998 ©Copyright: Jennifer Tupper, 1998 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Curriculum Studies The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date October ff . I 9 92? 11 ABSTRACT Two secondary social studies textbooks, Canada: A Nation Unfolding, and Canada Today were analyzed with regard to the inclusion of the lives, experiences, perspectives and contributions of females throughout history and today. Drawing on the existing literature,-a framework of analysis was created comprised of four categories: 1) language; 2) visual representation; 3) positioning and; 4) critical analysis of content. Each of these categories was further broken into a series of related subcategories in order to examine in depth and detail, the portrayal of women in these two textbooks. -

Interiors by Coleman Lemieux & Compagnie

INTERIORS by Coleman Lemieux & Compagnie An NAC co-production STUDY GUIDE National Arts Centre, Dance 2008–2009 Season Cathy Levy Producer, Dance Programming This study guide was prepared by Coleman Lemieux & Compagnie, DanceWorks education consultant Laurence Siegel and NAC Outreach Coordinator Renata Soutter for the National Arts Centre Dance Department, October 2008. This document may be used for educational purposes only. INTERIORS STUDY GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS About the NAC ……………………………………………… 1 Dance at the NAC ……………………………………………... 2 Theatre Etiquette ………………………………………….…. 3 Interiors Artistic Team and Synopsis .……………………. 4 What students can expect ………………………………..…… 5 About the Company …………………………………….. 7 About the Artistic Directors …………………….………………. 8 About the Dancers …………………………………….. 9 An interview with Laurence Lemieux …………………….. 10 Appreciating Contemporary Dance …………………….. 12 How to watch a performance ……….………….… 13 Pre- and post-performance activities ……………….……. 14 Bibliography/internet sites of interest …………………..… 18 1 Canada’s National Arts Centre Officially opened on June 2, 1969, the National Arts Centre was one of the key institutions created by Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson as the principal centennial project of the federal government. Built in the shape of a hexagon, the design became the architectural leitmotif for Canada's premier performing arts centre. Situated in the heart of the nation's capital across Confederation Square from Parliament Hill, the National Arts Centre is among the largest performing arts complexes in Canada. It is unique as the only multidisciplinary, bilingual performing arts centre in North America and features one of the largest stages on the continent. Designed by Fred Lebensold (ARCOP Design), one of North America's foremost theatre designers, the building was widely praised as a twentieth century architectural landmark. -

Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation

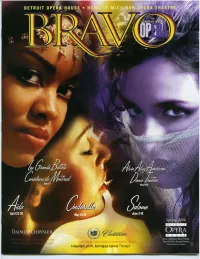

2006 Spring Opera Season is sponsored by Cadillac Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre LaSalle Bank salutes those who make the arts a part of our lives. Personal Banking· Commercial Banking· Wealth Management Making more possible LaSalle Bank ABN AMRO ~ www. la sal lebank.com t:.I Wealth Management is a division of LaSalle Bank, NA Copyright 2010,i'ENm Michigan © 2005 LaSalle Opera Bank NTheatre.A. Member FDIC. Equal Opportunity Lender. 2006 The Official MagaZine of the Detroit Opera House BRAVO IS A MICHI GAN OPERA THEAT RE P UB LI CATION Sprin",,---~ CONTRI BUTORS Dr. David DiChiera Karen VanderKloot DiChiera eason Roberto Mauro Michigan Opera Theatre Staff Dave Blackburn, Editor -wELCOME P UBLISHER Letter from Dr. D avid DiChiera ...... .. ..... ...... 4 Live Publishing Company Frank Cucciarre, Design and Art Direction ON STAGE Bli nk Concept &: Design, Inc. Production LES GRAND BALLETS CANADIENS de MONTREAL .. 7 Chuck Rosenberg, Copy Editor Be Moved! Differently . ............................... ... 8 Toby Faber, Director of Advertising Sales Physicians' service provided by Henry Ford AIDA ............... ..... ...... ... .. ... .. .... 11 Medical Center. Setting ................ .. .. .................. .... 12 Aida and the Detroit Opera House . ..... ... ... 14 Pepsi-Cola is the official soft drink and juice provider for the Detroit Opera House. C INDERELLA ...... ....... ... ......... ..... .... 15 Cadillac Coffee is the official coffee of the Detroit Setting . ......... ....... ....... ... .. .. 16 Opera House. Steinway is the official piano of the Detroit Opera ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER .. ..... 17 House and Michigan Opera Theatre. Steinway All About Ailey. 18 pianos are provided by Hammell Music, exclusive representative for Steinway and Sons in Michigan. SALOME ........ ... ......... .. ... ... 23 President Tuxedo is the official provider of Setting ............. .. ..... .......... ..... 24 formal wear for the Detroit Opera House. -

Cultural Diplomacy and Nation-Building in Cold War Canada, 1945-1967 by Kailey Miller a Thesis Submitt

'An Ancillary Weapon’: Cultural Diplomacy and Nation-building in Cold War Canada, 1945-1967 by Kailey Miller A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in History in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2015 Copyright ©Kailey Miller, 2015 Abstract This dissertation is a study of Canada’s cultural approaches toward the Communist world – particularly in the performing arts – and the ways in which the public and private sectors sought to develop Canada’s identity during the Cold War. The first chapter examines how the defection of Igor Gouzenko in 1945 framed the Canadian state’s approach to the security aspects of cultural exchanges with the Soviet Union. Chapters 2 to 4 analyse the socio-economic, political, and international context that shaped Canada's music, classical theatre, and ballet exchanges with communist countries. The final chapter explores Expo ’67’s World Festival of Arts and Entertainment as a significant moment in international and domestic cultural relations. I contend that although focused abroad, Canada’s cultural initiatives served a nation-building purpose at home. For practitioners of Canadian cultural diplomacy, domestic audiences were just as, if not more, important as foreign audiences. ii Acknowledgements My supervisor, Ian McKay, has been an unfailing source of guidance during this process. I could not have done this without him. Thank you, Ian, for teaching me how to be a better writer, editor, and researcher. I only hope I can be half the scholar you are one day. A big thank you to my committee, Karen Dubinsky, Jeffrey Brison, Lynda Jessup, and Robert Teigrob. -

La Musique De Pierre Mercure À L'affiche De Spectacles De Danse

Document generated on 09/29/2021 4:42 a.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines La musique de Pierre Mercure à l’affiche de spectacles de danse Pierre Mercure’s music accompanies the dance Claudine Caron Musique automatiste ? Pierre Mercure et le Refus global Article abstract Volume 21, Number 3, 2011 Much of Pierre Mercure’s catalogue remains a mystery since many manuscripts are untraceable and tapes lost. Focusing on dance productions URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1006357ar that included his works, this article seeks to retrace their history based on DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1006357ar photographs, performance programs and newspaper articles. From this corpus we see how Mercure brought new thinking to composition through the years. See table of contents He took his writing in new directions, recasting the conventional concert format by using the tools and techniques of electroacoustic music. His works incorporated dancers and technical equipment along with special lighting and collaborators from the fine arts. In company with the Refus global artists, Publisher(s) Pierre Mercure was clearly a vital factor in the dissemination and reception of Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal contemporary music in Québec. ISSN 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Caron, C. (2011). La musique de Pierre Mercure à l’affiche de spectacles de danse. Circuit, 21(3), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.7202/1006357ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

2 Peaking with Verbal and Emotional Refinement, Gentle Calm, and A

( peaking with verbal and emotionalrefinement, gentle calm, and a modesty that nevertheless does not conceal great inner aepth, Fernand Nault tells the story ofh1s life. In his narrative,the events follow from one another, naturally and smoothly. They seem almost to arise by chance. But make no mistake: a career this exceptional cannot be the result of pure coincidence. A tremendouspassion, to which he has always been totally receptive, has made possible what initially seemed to be impossible, to belong in the realm of dreams. The Quebec of the 1930s, and the rest of Canada, for that matter, was a wasteland as far as ballet was concerned. There was no professional company anywhere, few touring companies, a mere handful of ballet schools, and a deep-rooted prejudice against dancers. Moreover, dance in general was the su6ject of a religious prohibition. How, in such surroundings, could a teenager from a poor family in Montreal1s Hochelaga-Maisonneuve districtdevelop such a taste for dancing that he wanted to make it his career? "I was strongly influenced by my grandmother. She loved social dancing and did a lot of it, even at tfie expense of her reputation. I also haa a fondness for the theatre:putting on a make-believe mass was theatre to me !'1 A French film, V etoi1e de Valencia, in which Birgit Helm danced a tango, was the trigger.It was love at first sight. While he could afford five cents to go to the movies, young Fernand did not have the means to pay for dancing lessons. Then he met Raoul Leblanc, a flower seller at the Hochefaga-Maisonneuve market, and a tap dancer. -

GGPAA Gala Program 2015 English

NatioNal arts CeNtre, ottawa, May 30, 2015 The arts engage and inspire us A nation’s ovation. We didn’t invest a lifetime perfecting our craft. Or spend countless hours on the road between performances. But as a proud presenting sponsor of the Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards, we did put our energy into recognizing outstanding Canadian artists who enrich the fabric of our culture. When the energy you invest in life meets the energy we fuel it with, Arts Nation happens. ’ work a O r i Explore the laureates’’ work at iTunes.com/GGPAA The Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards The Governor General’s Performing Arts Recipients of the National arts Centre award , Awards are Canada’s most prestigious honour which recognizes work of an extraordinary in the performing arts. Created in 1992 by the nature in the previous performance year, are late Right Honourable Ramon John Hnatyshyn selected by a committee of senior programmer s (1934–2002), then Governor General of from the National Arts Centre (NAC). This Canada, and his wife Gerda, the Awards are Award comprises a commemorative medallion, the ultimate recognition from Canadians for a $25,000 cash prize provided by the NAC, and Canadians whose accomplishments have a commissioned work created by Canadian inspired and enriched the cultural life of ceramic artist Paula Murray. our country. All commemorative medallions are generously Laureates of the lifetime artistic achievement donated by the Royal Canadian Mint . award are selected from the fields of classical The Awards also feature a unique Mentorship music, dance, film, popular music, radio and Program designed to benefit a talented mid- television broadcasting, and theatre. -

University Musical Society

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY Les Grands Ballets Canadians COPPELIA(1870) Saturday Evening, October 17, 1992, at 8:00 Sunday Afternoon, October 18, 1992, at 3:00 Power Center for the Performing Arts Ann Arbor, Michigan Choreography: Enrique Martinez after Marius Petipa Music: Leo Delibes Sets and Costumes: Peter Home Costumes Design Collaborator: Lydia Randolph Lighting: Nicholas Cernovitch Act I A village square The action evolves around Coppelia, the beautiful but enigmatic young daughter of Dr. Coppelius. Swanilda suspects her fiance, Frantz, of harboring a secret love for Coppelia. The burgermeister announces that tomorrow he will distribute dowries to the engaged couples of the village and urges Swanilda to wed Frantz. But possessed by jealousy, Swanilda breaks off the engagement. Night falls and the crowd disperses. As Coppelius leaves his house, he is jostled by a group of young men and drops his key. Swanilda finds the key and enters the forbidden house with her friends. Frantz, too, is attempting to enter the house when Coppelius returns unexpectedly. Act II Coppelius' workshop peopled with curious figures The young women overcome their initial timidity and boldly make their way through the house. Swanilda quickly discovers to her joy that Coppelia is only a mechanical doll. At this point, Coppelius suddenly appears and chases out the intruders, all but Swanilda who, hidden behind the curtain, takes the place of Coppelia. Coming upon Frantz, who has finally gotten into the house, Coppelius makes him drink a potion intended to pull the young man's vital force from his body and transfer it to the doll. -

20 Years of Inspiration

20 years of inspiration The arts engage and inspire us 20 years of inspiration National Arts Centre | Ottawa | May 5, 2012 20 years of inspiration Welcome to the 20th anniversary Governor General’s In 2007 the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) Performing Arts Awards Gala! joined the Awards Foundation as a creative partner, and agreed to produce a short film about each Award The Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards recipient (beginning with the 2008 laureates). After (GGPAA) were created in 1992 under the patronage of the late Right Honourable Ramon John Hnatyshyn premiering at the GGPAA Gala, these original and (1934–2002), 24th Governor General of Canada, engaging films are made available to all Canadians and his wife Gerda. on the Web and in a variety of digital formats. The idea for the GGPAA goes back to the late 2008 marked the launch of the GGPAA Mentorship 1980s and a discussion between Peter Herrndorf Program, a unique partnership between the Awards (now President and CEO of the National Arts Centre) Foundation and the National Arts Centre that pairs and entertainment industry executive Brian Robertson, a past award recipient with a talented artist in both of whom were involved at the time with the mid-career. (See page 34.) Toronto Arts Awards Foundation. When they “The Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards approached Governor General Hnatyshyn with are the highest tribute we can offer Canadian artists,” their proposal for a national performing arts awards said Judith LaRocque, former Deputy Minister of program, they received his enthusiastic support. Canadian Heritage and former Secretary to the “He became a tremendous fan of the artists receiving Governor General, in an interview on the occasion the awards each year, the perfect cheerleader in the of the 15th anniversary of the Awards.