Florence Nelson Kennedy FASHION ILLUSTRATOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

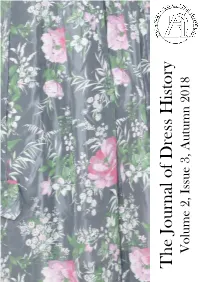

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

2017-2018 Updated Fashion Design

Fashion Design The Hoot Addendum #4 This addendum replaces the Fashion Design section (pages 231 – 238) of the 2017-18 The Hoot. Revised December 1, 2017 BACK TO CONTENTS | 231 FASHION DESIGN Innovation in fashion design results from a rigorous process of developing and editing ideas that address specific design challenges. Students in our program work alongside expert, professional faculty and guest mentors, who are current and visible designers, to become educated and practiced in all aspects of the design process. Throughout their experience, students produce original designs and develop collections for their portfolio. In their Junior and Senior year, students have the opportunity to work in teams to create unique designs under the guidance of mentors, emulating professional designers and following the industry's seasonal schedule. Recent mentors for the Junior and Senior class have included Anthropologie, Urban Outfitters, Nike, Roxy, Armani Exchange, BCBG, Trina Turk, Ruben & Isabel Toledo, and Bob Mackie. Junior and Senior designs are featured at the annual Scholarship Benefit and Fashion Show at the Beverly Hilton. FASHION DESIGN WITH AN EMPHASIS IN COSTUME DESIGN Students may choose to pursue an emphasis in Costume Design. With a focus on new directions in character development for film, television, live performance, concept art, and video, students emerge from the Costume Design Emphasis track as relevant, creative professionals prepared for the future direction of this exciting field. Under the guidance of critically-acclaimed costume design professionals and leading costume houses, students will produce original designs and dynamic illustrations, combining traditional and digital methods, for their portfolios. Costume Design mentors have included: Disney, Cirque du Soleil, Theadora Van Runkle, Betsy Heimann, Western Costume, Bill Travilla, and Bob Mackie. -

A Study of Fashion Art Illustration

Journal of Fashion Business Vol. 6, No. 3. pp.94~109(2002) A Study of Fashion Art Illustration Kang, Hee-Myung and Kim, Hye-Kyung* Lecturer, Doctoral, Dept. of Fashion Design, Dongduk Women’s University Professor, Dept. of Fashion Design, Dongduk Women’s University* Abstract The advent of the information age, advancement of the multi-media, and proliferation of internet are all ushering-in a new era of a cyber world. The artistic expression is unfolding into a new genre of a new era.. In the modern art, the boundary between the fine art and the applied art is becoming blurred, and further, distinction of fine art from popular art is also becoming meaningless. The advancement of science and technology, by offering new materials and visual forms, is contributing to the expansion of the morden art’s horizon. As fashion illustration is gaining recognition as a form of art which mirrors today’s realities, it has also become increasingly necessary to add variety and newness. Fashion illustration is thus becoming the visual language of the modern world, capable of conveying artistic emotion, and at the same time able to effectively communicate the image of fashion to the masses. The increasing awareness of artistic talent and ingenuity as essential components of fashion illustration is yielding greater fusion between fashion illustration and art &technology. This has resulted in the use of the advanced computer technology as a tool for crafting artistic expressions, such as fashion illustration, and this new tool has opened-up new possibilities for expressing images and colors. Further, the computer-aided fashion illustration is emerging as a new technique for expression. -

The Language of Clothes: Curriculum Evalua Tion of Four Fashion Design and Merchandising Programs in Canada

THE LANGUAGE OF CLOTHES: CURRICULUM EVALUA TION OF FOUR FASHION DESIGN AND MERCHANDISING PROGRAMS IN CANADA JUDI DORMAAR B.A., University of Lethbridge, 1993 A Project Submitted to the Faculty of Education of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF EDUCATION Lethbridge, Alberta February 2003 111 Abstract A high level of educational attainment carries both economic and social benefits. The popularity of continuing education programs and adult high school completion programs attest to people's interest in educational development and to the growing importance of education, skills and training in today's workplace. In general, higher levels of educational attainment are associated with improved labour market outcomes. Employment rates increase and unemployment rates decrease with higher levels of education. Education in the area of Fashion Design and Merchandising is one such area that is continuing to grow and MUST grow to keep up with the dynamics of our society. Fashion in the global market and in Canada today is big business. Its component parts - the design, production and distribution of fashion merchandise - form the basis of a highly complex, multibillion-dollar industry. It employs the greatly diversified skills and talents of millions of people, offers a multitudinous mix of products, absorbs a considerable portion of consumer spending and plays a vital role in the country's economy. Almost every country in the world depends on the textile and apparel sectors as important contributors to their economy. In Canada, more and more people will need an increasing amount of training and retraining throughout their careers. -

Wfw19-Magazine-2

Apr/May 2019 WINCHESTER FASHION WEEK Complimentary #WFW19 Programme of Talks Workshops Showcases Shopping Experiences #INDIEWINCH EDIT Winchester’s fashion independents on Instagram Sponsored by Brought to you by @WinFashionWk A CELEBRATION OFwinchesterfashionweek.co.uk STYLE FREE FILM SCREENING The University of Winchester is proud to sponsor Winchester Fashion Week 2019 and to host a special free screening of an acclaimed fashion documentary that delves behind the scenes of 2015’s China-themed Met Gala, the fashion world’s most dynamic annual event. THE FIRST MONDAY IN MAY Hello & Welcome, e are delighted to warmly welcome you to the ninth annual Winchester Fashion Week coordinated by Winchester Business Improvement District (BID). W It’s lovely to meet you. Let’s start with the introductions… We are Sarah and Hannah from Winchester BID, who have worked together to produce and promote this year’s event. We are proud to present a fresh, new theme and programme for Winchester Fashion Week – A Celebration Of Style (WFW19). This includes in store shopping experiences, workshops, talks and showcases, as well as catwalk shows and a fashion fair. This year, we have revised and developed WFW19 to celebrate style in the city. We have introduced a new brand that pays homage to its heritage with a focus on sustainability, local charity and the city’s circular economy throughout the event. This year, we have revised and developed the 6 day event, which we see as a great way to bring local businesses together with some exciting collaborations, interesting presentations and to showcase all things new on offer in Winchester, whilst building subjects like sustainability, local charity and the city’s circular economy into the proceedings. -

101 CC1 Concepts of Fashion

CONCEPT OF FASHION BFA(F)- 101 CC1 Directorate of Distance Education SWAMI VIVEKANAND SUBHARTI UNIVERSITY MEERUT 250005 UTTAR PRADESH SIM MOUDLE DEVELOPED BY: Reviewed by the study Material Assessment Committed Comprising: 1. Dr. N.K.Ahuja, Vice Chancellor Copyright © Publishers Grid No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduce or transmitted or utilized or store in any form or by any means now know or here in after invented, electronic, digital or mechanical. Including, photocopying, scanning, recording or by any informa- tion storage or retrieval system, without prior permission from the publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by Publishers Grid and Publishers. and has been obtained by its author from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the publisher and author shall in no event be liable for any errors, omission or damages arising out of this information and specially disclaim and implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Published by: Publishers Grid 4857/24, Ansari Road, Darya ganj, New Delhi-110002. Tel: 9899459633, 7982859204 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Printed by: A3 Digital Press Edition : 2021 CONTENTS 1. Introduction to Fashion 5-47 2. Fashion Forecasting 48-69 3. Theories of Fashion, Factors Affecting Fashion 70-96 4. Components of Fashion 97-112 5. Principle of Fashion and Fashion Cycle 113-128 6. Fashion Centres in the World 129-154 7. Study of the Renowned Fashion Designers 155-191 8. Careers in Fashion and Apparel Industry 192-217 9. -

Curriculum Vitae

IRINA TEVZADZE Fashion Design ● Fine Art 750 S Ash Ave., Apt 8039, Tempe, AZ 85281, USA. Tel: 1.573.777-2554 E-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] Web: www.irinatevzadze.com Summary: Irina Tevzadze is a designer, interdisciplinary artist and educator with more than 20 years of experience. As a fashion designer, she creates and has internationally showcased numerous collections of womenswear, childrenswear, accessories and uniforms and she has also designed collections for high-profile European fashion houses. As an artist, she works in a broad variety of traditional and digital media and her works have been exhibited and sold worldwide. In higher education, Ms. Tevzadze has taught undergraduate fashion and art courses, advised students and guided and supervised their submissions to prestigious fashion competitions. Education: MFA – 1998, BFA (Honors Diploma) – 1994 Department of Decorative and Applied Arts and Department of Design Tbilisi State Academy of Art, Tbilisi, Georgia Based on thorough research and cross-cultural synthesis, completed and defended several creative projects which presented innovative ideas and developed a methodology for forecasting future trends in fashion. This methodology was based on creative and innovative inter-connection of various shapes and forms, body postures, movement and motion, introduction of new color palettes and contemporary surface designs and patterns. Professional Experience: INTERDISCIPLINARY ARTIST, ILLUSTRATOR & DESIGNER – 1992 to present CO-FOUNDER and CREATIVE DIRECTOR – 2005 to present “sakartvelo.com” LLC, Tbilisi, Georgia Co-founded design and communication consulting company and oversees the creative for the company’s commercial projects; worked on corporate and personality branding projects, designed clients’ corporate identity visuals and developed communication strategies; led design and development of company products and supervised their production. -

Marangoni /Life Mutation Start /The Real Transformation

SHORT COURSES & STUDY ABROAD SEMESTER COURSES MARANGONI /LIFE MUTATION START /THE REAL TRANSFORMATION 2 3 /INDEX 7 MARANGONI 36 INTERIOR /LIFE MUTATION /DESIGN 9 THE INTERNATIONAL COLLECTION 37 INTERIOR DESIGN /OF HIGH-END, PRESTIGIOUSLY /FOR PROFESSIONALS LOCATED, MULTICULTURAL SCHOOLS 38 PRODUCT 11 A HISTORY /DESIGN /IN FASHION, DESIGN & ART 39 DIGITAL 13 MARANGONI /GRAPHIC DESIGN /DNA 40 ART IN /FASHION 15 EIGHT CAPITALS /ALWAYS AT THE CENTRE OF STYLE 41 FASHION /PHOTOGRAPHY 17 THE FIRST STEP TO EXPERTISE /A SHORT COURSE 42 FASHION & /THE CITIES 18 FASHION /DESIGN 44 STUDY ABROAD /Undergraduate Semester Courses 19 INTERIOR & /PRODUCT DESIGN 45 FASHION /DESIGN Semester 20 STYLING PHOTOGRAPHY /FOR SOCIAL MEDIA 46 FASHION DESIGN & /WOMENSWEAR Semester 21 STYLE YOURSELF /MY FASHION PROFILE 47 FASHION DESIGN & /ACCESSORIES Semester 22 T-SHIRT DESIGN /AN ARTWORK 48 FASHION STYLING & /CREATIVE DIRECTION Semester 23 THE MADE IN ITALY /MIX OF FASHION, 49 FASHION STYLING & DESIGN & ART /VISUAL MERCHANDISING Semester FASHION 24 DISCOVER THE 50 /HAUTE COUTURE /BUSINESS Semester CAPITAL OF FASHION 51 FASHION BUSINESS & /BUYING Semester 25 EXPLORE TRENDS /FROM STREET TO LUXURY 52 FASHION BUSINESS /COMMUNICATION & MEDIA Semester 26 ACCESSORIES /DESIGN 53 INTERIOR /DESIGN Semester 27 TREND /FORECASTING 54 PRODUCT FASHION VISUAL /DESIGN Semester 28 /MERCHANDISING 55 VISUAL /DESIGN Semester 29 FASHION /DESIGN 56 MULTIMEDIA /ARTS Semester 30 FASHION IMAGE & /STYLING 57 ART HISTORY & /CULTURE Semester 31 FASHION /BUSINESS 58 STUDY ABROAD /Postgraduate (Graduate) Semester Courses 32 FASHION IMAGE & /BUSINESS 59 FASHION BUYING & /MERCHANDISING Semester 33 FASHION FOLLOWERS /SOCIAL MEDIA & BLOGGING 60 FASHION BUSINESS & /MARKETING Semester 34 FASHION /BUYING 61 ADVANCED /INTERIOR DESIGN Semester 35 MARKETING /FOR LUXURY 62 CONTACTS & /CREDITS 4 5 MARANGONI /LIFE MUTATION There are some experiences in life that lead to a radical transformation, a life mutation, where what comes after is lightyears ahead of what preceded it. -

Redefining the High Art of Couture: Fashion Illustration Goes Modern

Redefining the High Art of Couture: Fashion Illustration Goes Modern exhibition curated by Decue Wu Tuesday, April 30, 2013 Fashion illustration has a long history and has played a critical role in the fashion industry. In the past, fashion illustrations were the main avenue for presenting the glamorous fashion concepts of designers. The illustrators added their own elements into their illustrations while showing the designerʼs vision. Meanwhile, fashion illustrators also documented the fashion show as editorial illustrations for magazines, newspapers and other publications. Yves Saint Laurent drawing designs. 1957 Tuesday, April 30, 2013 Cover illustration by Benito, 1921, for Vogue, February 15, 1921. Cover illustration by Benito, 1929, for Vogue, August 1929. Tuesday, April 30, 2013 Exhibition Précis: Redefining the High Art of Couture: Fashion Illustration Goes Modern is an exhibition that asserts that fashion illustration is a fine art. The focus is on the fashion illustrations of notable contemporary fashion illustrators, including David Downton (1959), Gladys Perint Palmer, Tanya Ling (1966), Francois Berthoud (1961), Mats Gustafson (1951), Zoë Taylor (1982), Jean-Philippe Delhomme (1959) and Howard Tangye (1979). Approximately two to four illustrations showcase the remarkable artistic talents of each artist. This exhibition is meaningful because it dispels the idea that fashion illustration is merely a functional tool for a fashion house— one used either to instruct tailors or to be manipulated as a marketing-and-sales device in fashion magazines or blogs. Instead, these exquisite drawings lift fashion illustration to its rightful place—as a high-art form worthy of acquisition by a museum or a private collector. -

D8 Fashion Show Letter

D8 4-H CLOTHING & TEXTILES EVENTS District Contest Information Date: Tuesday, April 17, 2018 Location: Bell County Expo Center 301 W Loop 121, Belton, TX 76513 www.bellcountyexpo.com Time: • See attached schedule. • The Fashion Show & Duds to Dazzle Contests will be held on the same day. 4-H members may participate in both events. They will be judged in Fashion Show first, then compete in Duds to Dazzle. • The concession stand will be open to purchase food for lunch or snacks. • The schedule is TENTATIVE until entries are received and processed. Deadlines: Please see your County Extension Agent for registration requirements and deadline. http://counties.agrilife.org/ Senior Paperwork for Senior Fashion Show (Buying, Construction, Natural Fiber) must be uploaded Paperwork: on 4-H Connect by the deadline. Junior and Paperwork for Junior and Intermediate Fashion Show participants will not be judged prior Intermediate to the day of the Fashion Show. Participants will bring two copies of their paperwork with Paperwork: them to the contest. Storyboards: In addition to the registration on 4-H Connect by March 23 the Storyboard must be physically in the McLennan County Extension Office by Tuesday, March 27 at 10 am. • All Storyboards must be received by this date. They must be PHYSICALLY in the McLennan County Extension Office by this date and time. Consider working with surrounding counties to make a plan to deliver them. They will most likely not withstand shipping. • If you want to deliver them to Stephenville, make sure they are received by Monday, March 26 so Laura can take them to Waco. -

PROGRAMS of STUDY

PROGRAMS of STUDY FIDM’S curriculum is intense, concentrated, and rewarding. The college prepares students to enter the global industries of Fashion, Visual Arts, Interior Design, and Entertainment. Our graduates enter the market as highly trained professionals, ready to make a contribution. We offer Associate of Arts, A.A. Professional Designation, A.A. Advanced Study, Bachelor’s, and Master’s Degree programs designed to enhance a variety of educational backgrounds. Every program leads to a degree. Our curriculum has been developed, and is continually updated, to reflect the needs of each industry served by our majors. PROGRAMS OF STUDY 23 Associate of Arts Acceptance to the Professional Degree Programs Designation Program is contingent upon: Associate of Arts Programs are designed U.S. Students: for students who have a high school diploma 1. Possession of a U.S. regionally accredited or the recognized equivalent. These programs Associate, Bachelor’s, or Master’s degree. offer the highly specialized curriculum of 2. Associate of Applied Science degrees or a specific major, as well as a traditional non-accredited degrees will be evaluated liberal arts/general studies foundation: to verify that a sufficient number of – Apparel Industry Management liberal arts requirements have been met – Beauty Industry Merchandising & Marketing to gain acceptance into the Associate of – Digital Media* Arts Professional Designation degree – Fashion Design* programs. – Fashion Knitwear Design* International Students: – Footwear Design & Development* 1. A certified International degree equivalent – Graphic Design* to a U.S. accredited Associate, Bachelor’s, – Interior Design* or Master’s degree. – Jewelry Design* 2. TOEFL score of 183 (computer based) – Merchandising & Marketing or 65 (Internet based) –OR– successful – Merchandise Product Development passing of FIDM’s Essay and English – Social Media Placement Exam. -

Irina Press Release 1-31-13

FFPR Fran Fried 29 Chandler Dr. Prospect, CT 06712 203-695-9238 [email protected] World-class fashion design in Connecticut: New England Fashion+Design Association in SoNo and coming to Hartford SOUTH NORWALK, CT – There’s no need to head into New York to learn fashion design when you soon will have two places in Connecticut. New England Fashion+Design Association has been located in the South Norwalk Metro-North railroad station (at 25B Monroe St.) since 2006, And now, director and co-founder Irina Simeonova has announced a Fashion Lab Summer Camp, to take place June 25-Aug. 2 in Hartford (at 75 Charter Oak Ave.). At NEF+DA, aspiring designers of all ages can learn what it takes to express themselves and create works for the runway or everyday wear, to go on to jobs in the fashion world, to launch their own businesses, or to get a world-class design background before heading to college. And the Fashion Lab Summer Camp will offer lessons in illustrating, pattern making and design. “There are many people here who don’t want to travel,” Irina said. “They’re intimidated by the big city, but they desperately want to change their lives. You don’t have to be in New York. We do go to New York for fabric trips and meet people. But I can give them New York here.” Students of all ages, from children to seniors, can take a variety of programs to study fashion illustration, pattern making and sewing – learning how to transform the visions strutting in their heads and apply them to pen and ink, to fabric and to sewing machines.