A Study of the Web Sites of Canadian Wineries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author' s Permission) p CLASS ACTS: CULINARY TOURISM IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR by Holly Jeannine Everett A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2005 St. John's Newfoundland ii Class Acts: Culinary Tourism in Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract This thesis, building on the conceptual framework outlined by folklorist Lucy Long, examines culinary tourism in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. The data upon which the analysis rests was collected through participant observation as well as qualitative interviews and surveys. The first chapter consists of a brief overview of traditional foodways in Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as a summary of the current state of the tourism industry. As well, the methodology which underpins the study is presented. Chapter two examines the historical origins of culinary tourism and the development of the idea in the Canadian context. The chapter ends with a description of Newfoundland and Labrador's current culinary marketing campaign, "A Taste of Newfoundland and Labrador." With particular attention to folklore scholarship, the course of academic attention to foodways and tourism, both separately and in tandem, is documented in chapter three. The second part of the thesis consists of three case studies. Chapter four examines the uses of seal flipper pie in hegemonic discourse about the province and its culture. Fried foods, specifically fried fish, potatoes and cod tongues, provide the starting point for a discussion of changing attitudes toward food, health and the obligations of citizenry in chapter five. -

Regulatory and Institutional Developments in the Ontario Wine and Grape Industry

International Journal of Wine Research Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article OrigiNAL RESEARCH Regulatory and institutional developments in the Ontario wine and grape industry Richard Carew1 Abstract: The Ontario wine industry has undergone major transformative changes over the last Wojciech J Florkowski2 two decades. These have corresponded to the implementation period of the Ontario Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) Act in 1999 and the launch of the Winery Strategic Plan, “Poised for 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Pacific Agri-Food Research Greatness,” in 2002. While the Ontario wine regions have gained significant recognition in Centre, Summerland, BC, Canada; the production of premium quality wines, the industry is still dominated by a few large wine 2Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of companies that produce the bulk of blended or “International Canadian Blends” (ICB), and Georgia, Griffin, GA, USA multiple small/mid-sized firms that produce principally VQA wines. This paper analyzes how winery regulations, industry changes, institutions, and innovation have impacted the domestic production, consumption, and international trade, of premium quality wines. The results of the For personal use only. study highlight the regional economic impact of the wine industry in the Niagara region, the success of small/mid-sized boutique wineries producing premium quality wines for the domestic market, and the physical challenges required to improve domestic VQA wine retail distribution and bolster the international trade of wine exports. Domestic success has been attributed to the combination of natural endowments, entrepreneurial talent, established quality standards, and the adoption of improved viticulture practices. -

Media Kit the Wines of British Columbia “Your Wines Are the Wines of Sensational!” British Columbia ~ Steven Spurrier

MEDIA KIT THE WINES OF BRITISH COLUMBIA “YOUR WINES ARE THE WINES OF SENSATIONAL!” BRITISH COLUMBIA ~ STEVEN SPURRIER British Columbia is a very special place for wine and, thanks to a handful of hard-working visionaries, our vibrant industry has been making a name for itself nationally and internationally for the past 25 years. “BC WINE OFTEN HAS In 1990, the Vintner’s Quality Alliance (VQA) standard was created to guarantee consumers they A RADICAL FRESHNESS were drinking wine made from 100% BC grown grapes. Today, BC VQA Wines dominate wine sales AND A REMARKABLE in British Columbia, and our wines are finding their way to more places than ever before, winning ABILITY TO DEFY over both critics and consumers internationally. THE CONVENTIONAL CATEGORIES OF TASTE.” The Wines of British Columbia truly are a reflection of the land where the grapes are grown and the exceptional people who craft them. We invite you to join us to savour all that makes the Wines of STUART PIGOTT British Columbia so special. ~ “WHAT I LOVE MOST ABOUT BC WINES IS THEY MIMIC THE PLACE, THEY MIMIC THE PURITY. YOU LOOK OUT AND FEEL THE AIR, TASTE THE WATER AND LOOK AT THE LAKE AND YOU CAN’T HELP BUT BE STRUCK BY A SENSE OF PURITY AND IT CARRIES OVER TO THE WINE. THEY HAVE PURITY AND A SENSE OF WEIGHTLESSNESS WHICH IS VERY ETHEREAL AND CAPTIVATING.” ~ KAREN MACNEIL DID YOU KNOW? • British Columbia’s Vintners Quality Alliance (BC VQA) designation celebrated 25 years of excellence in 2015. • BC’s Wine Industry has grown from just 17 grape wineries in 1990 to more than 275 today (as of January 2017). -

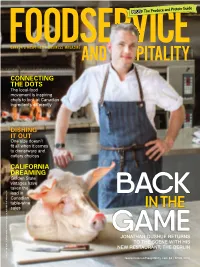

Connecting the Dots

CONNECTING THE DOTS The local-food movement is inspiring chefs to look at Canadian ingredients differently DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to dinnerware and cutlery choices CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden State vintages have taken the lead in Canadian table-wine sales JONATHAN GUSHUE RETURNS TO THE SCENE WITH HIS NEW RESTAURANT, THE BERLIN CANADIAN PUBLICATION MAIL PRODUCT SALES AGREEMENT #40063470 CANADIAN PUBLICATION foodserviceandhospitality.com $4 | APRIL 2016 VOLUME 49, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2016 CONTENTS 40 27 14 Features 11 FACE TIME Whether it’s eco-proteins 14 CONNECTING THE DOTS The 35 CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden or smart technology, the NRA Show local-food movement is inspiring State vintages have taken the lead aims to connect operators on a chefs to look at Canadian in Canadian table-wine sales host of industry issues ingredients differently By Danielle Schalk By Jackie Sloat-Spencer By Andrew Coppolino 37 DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit 22 BACK IN THE GAME After vanish - all when it comes to dinnerware and ing from the restaurant scene in cutlery choices By Denise Deveau 2012, Jonathan Gushue is back CUE] in the spotlight with his new c restaurant, The Berlin DEPARTMENTS By Andrew Coppolino 27 THE SUSTAINABILITY PARADIGM 2 FROM THE EDITOR While the day-to-day business of 5 FYI running a sustainable food operation 12 FROM THE DESK is challenging, it is becoming the new OF ROBERT CARTER normal By Cinda Chavich 40 CHEF’S CORNER: Neil McCue, Whitehall, Calgary PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY [NEIL M OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE FOODSERVICEANDHOSPITALITY.COM FOODSERVICE AND HOSPITALITY APRIL 2016 1 FROM THE EDITOR For daily news and announcements: @foodservicemag on Twitter and Foodservice and Hospitality on Facebook. -

Wine Tourism Insight

Wine Tourism Product BUILDING TOURISM WITH INSIGHT WINE October 2009 This profile summarizes information on the British Columbia wine tourism sector. Wine tourism, for the purpose of this profile, includes the tasting, consumption or purchase of wine, often at or near the source, such as wineries. Wine tourism also includes organized education, travel and celebration (i.e. festivals) around the appreciation of, tasting of, and purchase of wine. Information provided here includes an overview of BC’s wine tourism sector, a demographic and travel profile of Canadian and American travellers who participated in wine tourism activities while on pleasure trips, detailed information on motivated wine travellers to BC, and other outdoor and cultural activities participated in by wine travellers. Also included are overall wine tourism trends as well as a review of Canadian and US wine consumption trends, motivation factors of wine tourists, and an overview of the BC wine industry from the supply side. Research in this report has been compiled from several sources, including the 2006 Travel Activities and Motivations Study (TAMS), online reports (i.e. www.winebusiness.com), Statistics Canada, Wine Australia, (US) Wine Market Council, Winemakers Federation of Australia, Tourism New South Wales (Australia) and the BC Wine Institute. For the purpose of this tourism product profile, when describing results from TAMS data, participating wine tourism travellers are defined as those who have taken at least one overnight trip in 2004/05 where they participated in at least one of three wine tourism activities (1) Cooking/Wine tasting course; (2) Winery day visits; or (3) Wine tasting school. -

Quantification Économique Des Externalités Liées Aux Intrants Agricoles De La Viticulture Au Canada Et Au Québec

QUANTIFICATION ÉCONOMIQUE DES EXTERNALITÉS LIÉES AUX INTRANTS AGRICOLES DE LA VITICULTURE AU CANADA ET AU QUÉBEC. Par Sophie Bélair-Hamel Essai présenté au Centre universitaire de formation en environnement et développement durable en vue de l’obtention du grade de maître en environnement (M.Env.) Sous la direction de Monsieur Martin Comeau MAÎTRISE EN ENVIRONNEMENT UNIVERSITÉ DE SHERBROOKE Septembre 2017 SOMMAIRE Mots clés : viticulture, agriculture, biologique, conventionnelle, externalités, quantification, économique, pesticide, intrant de synthèse Au Québec comme au Canada, l’agriculture est très présente, autant par son histoire que par son influence économique, sociale et culturelle. Dans le contexte actuel, l’industrie agricole est importante comme secteur économique du pays, mais elle se doit d’intégrer des pratiques plus durables afin de protéger la société et l’environnement. Cet essai compare deux types d’agriculture, soit conventionnel et biologique. L’objectif principal de l’essai est de quantifier économiquement les externalités environnementales et sociales liées aux intrants agricoles en viticulture au Canada et au Québec. Pour ce faire, les impacts environnementaux, sociétaux et économiques des activités agricoles conventionnelles et biologiques ont été analysés et décrits. Puisque l’agriculture englobe plusieurs cultures, il s’avère important de différencier les pratiques propres à la viticulture et sa consommation d’intrants agricoles. Puisque l’industrie vinicole du Québec comporte des activités agricoles et des activités de transformation, ces deux volets ont été analysés séparément quant à leurs activités économiques. La quantification économique des externalités viticoles canadienne s’est inspirée en grande partie sur l’étude de l’ITAB publiée en 2016, ainsi que sur de nombreuses études scientifiques internationales. -

President's Report

FISCAL 2018: 2nd PRESIDENT'S REPORT QUARTER REVIEW In what is clearly a vindication of Celebrate the Wines of British Columbia's growing potential as British Columbia a wine industry, both of collective reviews the work of the success and viability, Andrew Peller BC Wine Institute Ltd.'s $95 million-dollar purchase of during each quarter of three prestigious BC wineries, with a the fiscal year. subsequent $25 million investment over the next five years, can only be This 2nd quarter described as bullish for our industry as review covers activities a whole. that occurred during Miles Prodan July, August and These three wineries own 250 acres of BC vineyards, produce September 2017. 125,000 cases of wine, and recorded sales of $24.5 million in 2016. A publicly-run company headquartered in Ontario, Peller In this issue Estate Ltd. is welcoming these wineries into its existing portfolio President's Report of premium BC VQA wines that includes Sandhill Wines, Red Rooster Winery, and Conviction Wines (formerly Calona Message from BCWI Vineyard's BC VQA Artist Series Brand). The proprietors and Marketing Director company are no strangers to BC and remains one of the most Message from BCWI experienced producers of BC VQA Wine. Media Relations Manager It is inevitable that some will cry foul over a perceived takeover Market Dashboard of iconic 'estate' wineries considered among the forbearers of our BC VQA Wine industry by an organization that by its history Marketing Events and successes is simply categorized as 'large'. Realistically, Report however, this is a designation used only by the BC Wine Media Report Institute to ensure good governance and fair representation on Social Media Report its Board and bears no relevance to the commitment to our industry. -

Wedding Food & Beverage Wedding Entrées

wedding food & beverage 2021-22 wedding entrées Garlic Rosemary Chicken Whole chicken cut into 9-piece segments and slow roasted in a rosemary BBQ sauce. Braised Pork Shoulder Pork shoulder braised for 14-hours in our signature spice rub, Old Yale Sasquatch Stout, and house made BBQ sauce. Beef Tenderloin Tenderloin medallions pan seared and finished in the oven with a red wine reduction. Baked Salmon Filet Salmon baked with your choice of pineapple citrus salsa or creamy leek sauce and toasted almonds. Carved Honey Ham Baked honey glazed ham with a sweet grainy mustard. Blackened Chicken Grilled chicken breasts with your choice of Cajun creole or creamy spinach Florentine. Prime Rib Slow roasted prime rib with a red wine and herb au jus. Eggplant and Falafel Stuffed Peppers Roasted red peppers stuffed with eggplant, falafel, sautéed vegetables, and a tomato herb sauce. Black Bean and Chickpea Croquettes Black beans, corn, chickpeas, vegetables, and herbs hand pressed lightly breaded and then fried served with roasted tomato salsa. Ratatouille Layers of roasted vegetables slow roasted in tomato sauce. wedding food & beverage 2021-22 salads Seven-Leaf Mixed Heritage Greens with Assorted Dressings Caesar Salad with Fresh Asiago & Roasted Garlic Dressing Homestyle Potato Salad Greek Pasta Salad Salad Caprese Roasted Vegetable Salad with Balsamic Reduction Quinoa & Mixed Seven Bean Salad in an Herb Vinaigrette Fresh Dinner Rolls (included) starches Rainbow Potato with Herbes De Provence Olive Oil Roasted Rosemary Garlic Rainbow Potatoes Baked -

Culinary Chronicles

Culinary Chronicles The Newsletter of the Culinary Historians of Canada AUTUMN 2010 NUMBER 66 “Indian method of fishing on Skeena River,” British Columbia Dominion Illustrated Monthly, August 4, 1888 (Image courtesy of Mary Williamson) ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Contents President’s Message: We are now the In a Circular Line It All Comes Back Culinary Historians of Canada! 2 Vivien Reiss 16, 18 Members’ News 2 An Ode to Chili Sauce Indigenous Foodways of Northern Ontario Margaret Lyons 17, 18, 21 Connie H. Nelson and Mirella Stroink 3–5 Book Reviews: Speaking of Food, No. 2: More than Pachamama Caroline Paulhus 19 Pemmican: First Nations’ Food Words Foodies: Democracy and Distinction Gary Draper 6–8 in the Gourmet Foodscape Tea with an Esquimaux Lady 8 Anita Stewart 20 First Nation’s Ways of Cooking Fish 9 Just Add Shoyu Margaret Lyons 21 “It supplied such excellent nourishment” Watching What We Eat Dean Tudor 22 – The Perception, Adoption and Adaptation Punched Drunk Dean Tudor 22–23 of 17th-Century Wendat Foodways by the CHC Upcoming Events 23 French Also of Interest to Members 23 Amy Scott 10–15 About CHC 24 Lapin Braisé et Têtes de Violon 15 2 Culinary Chronicles _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ President’s Message: We are now the Culinary Historians of Canada! Thank you to everyone who voted on our recent resolution to change the Culinary Historians of Ontario to the Culinary Historians of Canada. This important decision deserved a vote from the whole membership, and it was well worth the effort of distributing and counting ballots. Just over 60% of members cast their ballots, favouring by a wide margin of 4:1 to change the organization's name. -

President & CEO Message

FISCAL 2020: FIRST QUARTERLY REVIEW IN THIS ISSUE Celebrate the Wines of British Columbia President & CEO Message reviews the work of the BC Wine Institute Marketing Director Report during each quarter of the fiscal year. Communications Director Report Media Report Summary This first quarterly review covers activities Quarterly Sales Report that occurred during April, May and June Marketing Events Manager Report 2019. Content Marketing Manager Report Wine Competition Results President & CEO Message The first quarter of a new fiscal year is an especially busy time and BCWI’s Fiscal 2020 Q1 was no exception. It is a time for reporting last year’s efforts and progress headway on the current year’s objectives. Regarding the former, this past year saw continued success for the BC wine industry highlighted fiscal year (March 2019) with litres market share for of BC VQA Wine sold in the province at an all-time high of 19.25 per cent - up 3.37 per cent (56,000 cases) over the previous year. More importantly, that growth continues to be relatively evenly distributed across all distribution channels with an average increase of 10.13 per cent except LRS which was down 3.14 per cent over last year. At the same time, headwinds are becoming evident with the overall BC market for wine (e.g. imports, etc.) down -1.48 per cent (135,000 cases) with many issues beyond our direct control including; continue restricted interprovincial trade; international trade challenges and litigation; innovation and growth in the refreshment beverage category and pending legalization of cannabis-infused products. -

Canada's Wine Associations

Take a Tour: Canada’s Wine Associations NATIONAL Canadian Vintners Association – www.canadianvintners.com The Canadian Wine Institute was created in 1967 and renamed in 2000 to the Canadian Vintners Association (CVA) to better reflect the growth of this dynamic industry. Today, CVA represents over 90% of all wine produced in Canada, including 100% Canadian, Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) wines and International-Canadian Blended (ICB) wine products. Its members are also engaged in the entire wine value chain: from grape growing, farm management, grape harvesting, research, wine production, bottling, retail sales and tourism. CVA holds the trademarks to Vintners Quality Alliance, Icewine and Wines of Canada. Stated Mission: To provide focused national leadership and strategic coherence to enable domestic and international success for the Canadian wine industry. PROVINCIAL BRITISH COLUMBIA British Columbia Wine Institute – www.winebc.org The British Columbia Wine Institute (BCWI) was created by the Provincial Government to give the wine industry an industry elected voice representing the needs of the BC wine industry, through the British Columbia Wine Act in 1990. In 2006, BCWI members voted to become a voluntary trade association with member fees to be based on BC wine sales. Today, BCWI plays a key role in the growth of BC’s wine industry and its members represent 95% of total grape wine sales and 94% of total BC VQA wine sales in British Columbia. Stated Mission: To champion the interests of the British Columbia wine industry and BC VQA wine through marketing, communications and advocacy of its products and experiences to all stakeholders. Additional British Columbia wine-related organizations: British Columbia Wine Authority – www.bcvqa.ca The British Columbia Wine Authority (BCWA) is an independent regulatory authority to which the Province of British Columbia has delegated responsibility for enforcing the Province’s Wines of Marked Quality Regulation, including BC VQA Appellation of origin system and certification of 100% BC wine origins. -

BRITISH COLUMBIA WINE AUTHORITY Unit #3, 7519 Prairie Valley Rd., Summerland BC, V0H 1Z4 Phone: 250-494-8896 Toll Free: 1-877-499-2872 Fax: 250-494-9737 ______

BRITISH COLUMBIA WINE AUTHORITY Unit #3, 7519 Prairie Valley Rd., Summerland BC, V0H 1Z4 Phone: 250-494-8896 Toll Free: 1-877-499-2872 Fax: 250-494-9737 _______________________________________________________________ LABELLING GUIDELINES (Updated November 29, 2018) Guidelines for the Labelling of British Columbia BC VQA Wines The following labelling guidelines have been compiled by the British Columbia Wine Authority based on the “Wines of Marked Quality Regulation, Approved and Ordered July, 27, 2018”, in order to provide wineries with appropriate guidance and further descriptions for the labelling of BC VQA wines. This guideline will only target certain sections of the Regulation, for complete information please refer to the “Wines of Marked Quality Regulation”. This guide is not intended to replace the Regulation and, if there is any conflict between the guidelines and the Regulation, the Regulation governs. Please contact to British Columbia Wine Authority directly if you have any labelling question which is not addressed in these guidelines. Label Reviews All wineries must submit a label to the British Columbia Wine Authority for review and pre-approval. There is no charge for this. These reviews will provide wineries with definitive guidance concerning compliance of proposed labels with the Regulation. All labels must receive an approval prior to the product receiving its final BC VQA designation. The BCWA strongly suggests that labels be sent in prior to final printing (as a proof) for preliminary approval. This will save you time and money. Please e-mail a PDF or other electronic format to [email protected], do not send faxes. While these reviews may also take into account the labelling requirements of other Federal and Provincial laws (such as CFIA), the British Columbia Wine Authority’s opinion concerning the application of such other laws is not binding on other regulatory agencies that may administer such other laws.