The European Union, Its Overseas Territories and Non-Proliferation: the Case of Arctic Yellowcake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nebraska Unicameral and Its Lasting Benefits, 76 Neb

Nebraska Law Review Volume 76 | Issue 4 Article 6 1997 The eN braska Unicameral and Its Lasting Benefits Kim Robak Nebraska Lieutenant Governor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation Kim Robak, The Nebraska Unicameral and Its Lasting Benefits, 76 Neb. L. Rev. (1997) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol76/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Kim Robak* The Nebraska Unicameral and Its Lasting Benefits TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................... 791 II. Background ........................................... 793 III. Why and How the Unicameral Works ................. 799 A. Organization ...................................... 800 B. Process ........................................... 802 C. Partisanship ...................................... 804 D. The Lobby ........................................ 804 IV. Why a Nonpartisan Unicameral Is Superior to a Bicameral System ..................................... 805 A. Duplication ....................................... 805 B. Representative and Open Process .................. 809 C. Nonpartisanship .................................. 810 D. Leadership ........................................ 812 E. Lobby ............................................. 814 F. Balance -

Internationale Übereinkünfte

7.3.2014 DE Amtsblatt der Europäischen Union L 68/1 II (Rechtsakte ohne Gesetzescharakter) INTERNATIONALE ÜBEREINKÜNFTE BESCHLUSS DES RATES vom 2. Dezember 2013 über den Abschluss des Protokolls zur Änderung des Übereinkommens über das öffentliche Beschaffungswesen (2014/115/EU) DER RAT DER EUROPÄISCHEN UNION — HAT FOLGENDEN BESCHLUSS ERLASSEN: gestützt auf den Vertrag über die Arbeitsweise der Europäischen Artikel 1 Union, insbesondere auf Artikel 207 Absatz 4 Unterabsatz 1 in Verbindung mit Artikel 218 Absatz 6 Buchstabe a Ziffer v, Das Protokoll zur Änderung des Übereinkommens über das öffentliche Beschaffungswesen wird hiermit im Namen der Eu auf Vorschlag der Europäischen Kommission, ropäischen Union genehmigt. nach Zustimmung des Europäischen Parlaments, Der Wortlaut des Protokolls ist diesem Beschluss beigefügt. in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe: Artikel 2 Der Präsident des Rates wird die Person(en) bestellen, die befugt (1) Nach Maßgabe des Artikels XXIV Absatz 7 Buchstaben b ist (sind), im Namen der Union die Annahmeurkunde gemäß und c des WTO-Übereinkommens über das öffentliche Absatz 3 des Protokolls und im Einklang mit Artikel XXIV Beschaffungswesen (Government Procurement Agreement — Absatz 9 des GPA von 1994 zu hinterlegen, um die Zustim GPA von 1994) wurden im Januar 1999 Verhandlungen mung der Union, durch das Protokoll gebunden zu sein, zum über die Überarbeitung des GPA von 1994 eingeleitet. Ausdruck zu bringen ( 1 ). (2) Die Verhandlungen wurden von der Kommission in Ab stimmung mit dem nach Artikel 207 Absatz 3 des Ver Artikel 3 trags über die Arbeitsweise der Europäischen Union ein Das Protokoll ist dahingehend auszulegen, dass es keine Rechte gerichteten Besonderen Ausschuss geführt. oder Pflichten begründet, die vor den Gerichten der Union oder der Mitgliedstaaten unmittelbar geltend gemacht werden kön (3) Am 15. -

Ix Viii the World by Income

The world by income Classified according to World Bank estimates of 2016 GNI per capita (current US dollars,Atlas method) Low income (less than $1,005) Greenland (Den.) Lower middle income ($1,006–$3,955) Upper middle income ($3,956–$12,235) Faroe Russian Federation Iceland Islands High income (more than $12,235) (Den.) Finland Norway Sweden No data Canada Netherlands Estonia Isle of Man (U.K.) Russian Latvia Denmark Fed. Lithuania Ireland U.K. Germany Poland Belarus Belgium Channel Islands (U.K.) Ukraine Kazakhstan Mongolia Luxembourg France Moldova Switzerland Romania Uzbekistan Dem.People’s Liechtenstein Bulgaria Georgia Kyrgyz Rep.of Korea United States Azer- Rep. Spain Monaco Armenia Japan Portugal Greece baijan Turkmenistan Tajikistan Rep.of Andorra Turkey Korea Gibraltar (U.K.) Syrian China Malta Cyprus Arab Afghanistan Tunisia Lebanon Rep. Iraq Islamic Rep. Bermuda Morocco Israel of Iran (U.K.) West Bank and Gaza Jordan Bhutan Kuwait Pakistan Nepal Algeria Libya Arab Rep. Bahrain The Bahamas Western Saudi Qatar Cayman Is. (U.K.) of Egypt Bangladesh Sahara Arabia United Arab India Hong Kong, SAR Cuba Turks and Caicos Is. (U.K.) Emirates Myanmar Mexico Lao Macao, SAR Haiti Cabo Mauritania Oman P.D.R. N. Mariana Islands (U.S.) Belize Jamaica Verde Mali Niger Thailand Vietnam Guatemala Honduras Senegal Chad Sudan Eritrea Rep. of Guam (U.S.) Yemen El Salvador The Burkina Cambodia Philippines Marshall Nicaragua Gambia Faso Djibouti Federated States Islands Guinea Benin Costa Rica Guyana Guinea- Brunei of Micronesia Bissau Ghana Nigeria Central Ethiopia Sri R.B. de Suriname Côte South Darussalam Panama Venezuela Sierra d’Ivoire African Lanka French Guiana (Fr.) Cameroon Republic Sudan Somalia Palau Colombia Leone Togo Malaysia Liberia Maldives Equatorial Guinea Uganda São Tomé and Príncipe Rep. -

The Value of Nature in the Caribbean Netherlands

The Economics of Ecosystems The value of nature and Biodiversity in the Caribbean Netherlands in the Caribbean Netherlands 2 Total Economic Value in the Caribbean Netherlands The value of nature in the Caribbean Netherlands The Challenge Healthy ecosystems such as the forests on the hillsides of the Quill on St Eustatius and Saba’s Mt Scenery or the corals reefs of Bonaire are critical to the society of the Caribbean Netherlands. In the last decades, various local and global developments have resulted in serious threats to these fragile ecosystems, thereby jeopardizing the foundations of the islands’ economies. To make well-founded decisions that protect the natural environment on these beautiful tropical islands against the looming threats, it is crucial to understand how nature contributes to the economy and wellbeing in the Caribbean Netherlands. This study aims to determine the economic value and the societal importance of the main ecosystem services provided by the natural capital of Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba. The challenge of this project is to deliver insights that support decision-makers in the long-term management of the islands’ economies and natural environment. Overview Caribbean Netherlands The Caribbean Netherlands consist of three islands, Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba all located in the Caribbean Sea. Since 2010 each island is part of the Netherlands as a public entity. Bonaire is the largest island with 16,000 permanent residents, while only 4,000 people live in St Eustatius and approximately 2,000 in Saba. The total population of the Caribbean Netherlands is 22,000. All three islands are surrounded by living coral reefs and therefore attract many divers and snorkelers. -

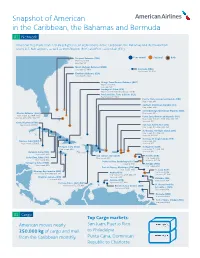

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network American flies more than 170 daily flights to 38 destinations in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda from seven U.S. hub airports, as well as from Boston (BOS) and Fort Lauderdale (FLL). Freeport, Bahamas (FPO) Year-round Seasonal Both Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Marsh Harbour, Bahamas (MHH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA Bermuda (BDA) Year-round: JFK, PHL Eleuthera, Bahamas (ELH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA George Town/Exuma, Bahamas (GGT) Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Santiago de Cuba (SCU) Year-round: MIA (Coming May 3, 2019) Providenciales, Turks & Caicos (PLS) Year-round: CLT, MIA Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic (POP) Year-round: MIA Santiago, Dominican Republic (STI) Year-round: MIA Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (SDQ) Nassau, Bahamas (NAS) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD Punta Cana, Dominican Republic (PUJ) Seasonal: DCA, DFW, LGA, PHL Year-round: BOS, CLT, DFW, MIA, ORD, PHL Seasonal: JFK Grand Cayman (GCM) Year-round: CLT, MIA San Juan, Puerto Rico (SJU) Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD, PHL St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands (STT) Year-round: CLT, MIA, SJU Seasonal: JFK, PHL St. Croix, US Virgin Islands (STX) Havana, Cuba (HAV) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA Seasonal: CLT Holguin, Cuba (HOG) St. Maarten (SXM) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, PHL Varadero, Cuba (VRA) Seasonal: JFK Year-round: MIA Cap-Haïtien, Haiti (CAP) St. Kitts (SKB) Santa Clara, Cuba (SNU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT, JFK Pointe-a-Pitre, Guadeloupe (PTP) Camagey, Cuba (CMW) Seasonal: MIA Antigua (ANU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Fort-de-France, Martinique (FDF) Year-round: MIA St. -

St. Lucia Earns Junior Chef Award at Taste Of

MEDIA CONTACTS: KTCpr Theresa M. Oakes / [email protected] Leigh-Mary Hoffmann / [email protected] Telephone: 516-594-4100 #1101 **high resolution images available** BAHAMAS WINS TEAM, BARTENDER, PASTRY TOP HONORS; PUERTO RICO TAKES CHEF CATEGORY; ST. LUCIA EARNS JUNIOR CHEF AWARD AT TASTE OF THE CARIBBEAN 2015 MIAMI, FL (June 15, 2015) – The Bahamas National Culinary Team won three of the five top categories at the Taste of the Caribbean culinary competition this past weekend earning honors as Caribbean National Team of the Year and individual honors to Marv Cunningham, Bahamas for Caribbean Bartender of the Year and four-time winner Sheldon Tracey Sweeting, Bahamas, for Caribbean Pastry Chef of the Year. Jonathan Hernandez, Puerto Rico was crowned Caribbean Chef of the Year and Edna Butcher, St. Lucia, was named Caribbean Junior Chef of the Year. "Congratulations to all of the Taste of the Caribbean participants, their national hotel associations, team managers and sponsors for developing 10 Caribbean national culinary teams to compete at our annual culinary event," said Frank Comito, director general and CEO of the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association (CHTA). "Your commitment to culinary excellence in our region is very much appreciated as we showcase the region’s culinary and beverage offerings. Congratulations to all of the winners for a job well-done," Comito added. Presented by CHTA, Taste of the Caribbean featured cooking and bartending competitions between 10 Caribbean culinary teams from Anguilla, Bahamas, Barbados, Bonaire, British Virgin Islands, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Lucia, Suriname and the U.S. Virgin Islands with the winners being named the "best of the best" throughout the region. -

Het Koninkrijk Tegen Het Licht

Het Koninkrijk tegen het licht Rechtsvergelijkend onderzoek in opdracht van de Tweede Kamer der Staten- Generaal naar de staatsrechtelijke overzeese verhoudingen in het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden, de Franse Republiek, het Koninkrijk Denemarken en het Verenigd Koninkrijk van Groot-Brittannië en Noord-Ierland prof. mr. H.G. Hoogers mr. G. Karapetian april 2019 INHOUDSOPGAVE Inleiding en aanleiding tot het onderzoek 3 Hoofdstuk 1 Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden 7 §1. Inleiding 7 §2. Een smalle rechtsband 8 §3. Democratische vertegenwoordiging 9 §4. Sociaaleconomische verhoudingen 10 §5. Financiën 11 §6. Defensie en openbare orde 11 §7. De beslechting van geschillen 13 Hoofdstuk 2 De Franse Republiek 16 §1. Inleiding 16 §2. Les collectivités territoriales: DrOM, COM en Nieuw-Caledonië 17 §3. Democratische vertegenwoordiging 21 §4. Sociaaleconomische verhouding en financiën 22 §5. Defensie en openbare orde 23 §6. De beslechting van geschillen 23 §7. Conclusie 24 Hoofdstuk 3 Het Koninkrijk Denemarken 25 §1. Inleiding; de structuur van het Deense Rijk 25 §2. De rechtsband tussen Denemarken en de beide andere Rijksdelen 29 §3. Democratische vertegenwoordiging 30 §4. Sociaaleconomische verhoudingen 31 §5. Financiën en openbare orde 31 §6. Defensie 31 §7. De beslechting van geschillen 32 §8. Conclusie 33 Hoofdstuk 4 Het Verenigd Koninkrijk van Groot-Brittannië en Noord-Ierland 35 §1. Inleiding 35 §2. Veertien Constituties voor veertien British Overseas Territories 37 §3. Democratische vertegenwoordiging 39 §4. Sociaaleconomische verhouding en financiën 41 §5. Defensie en openbare orde 42 §6. De beslechting van geschillen 42 §7. Conclusie 43 Hoofdstuk 5. Conclusies 44 §1. De structuur van de staatkundige relaties 44 §2. Democratische vertegenwoordiging 46 §3. -

Tekst Zrewidowanego Porozumienia

ISSN 1977-0766 Dziennik Urzędowy L 68 Unii Europejskiej Tom 57 Wydanie polskie Legislacja 7 marca 2014 Spis treści II Akty o charakterze nieustawodawczym UMOWY MIĘDZYNARODOWE 2014/115/UE: ★ Decyzja Rady z dnia 2 grudnia 2013 r. dotycząca zawarcia Protokołu zmieniającego Porozu mienie w sprawie zamówień rządowych . 1 Protokół zmieniający Porozumienie w sprawie zamówień rządowych . 2 Cena: 10 EUR Akty, których tytuły wydrukowano zwykłą czcionką, odnoszą się do bieżącego zarządzania sprawami rolnictwa i generalnie zachowują ważność przez określony czas. Tytuły wszystkich innych aktów poprzedza gwiazdka, a drukuje się je czcionką pogrubioną. PL 7.3.2014 PL Dziennik Urzędowy Unii Europejskiej L 68/1 II (Akty o charakterze nieustawodawczym) UMOWY MIĘDZYNARODOWE DECYZJA RADY z dnia 2 grudnia 2013 r. dotycząca zawarcia Protokołu zmieniającego Porozumienie w sprawie zamówień rządowych (2014/115/UE) RADA UNII EUROPEJSKIEJ, PRZYJMUJE NINIEJSZĄ DECYZJĘ: uwzględniając Traktat o funkcjonowaniu Unii Europejskiej, Artykuł 1 w szczególności jego art. 207 ust. 4 akapit pierwszy w związku z art. 218 ust. 6 lit. a) ppkt (v), Protokół zmieniający Porozumienie w sprawie zamówień rządo wych zostaje niniejszym zatwierdzony w imieniu Unii Europej skiej. uwzględniając wniosek Komisji Europejskiej, Tekst Protokołu jest załączony do niniejszej decyzji. uwzględniając zgodę Parlamentu Europejskiego, Artykuł 2 a także mając na uwadze, co następuje: Przewodniczący Rady wyznacza osobę lub osoby umocowane do złożenia instrumentu akceptacji w imieniu Unii, jak okre (1) Negocjacje dotyczące rewizji Porozumienia w sprawie ślono w ust. 3 Protokołu oraz zgodnie z art. XXIV ust. 9 GPA zamówień rządowych (w ramach GPA z 1994 r.) zostały z 1994 r., w celu wyrażenia zgody Unii Europejskiej na zwią zainicjowane w styczniu 1999 r. -

Aruba Country Profile Health in the Americas 2007

Aruba Netherlands Antilles Colombia ARUBA Venezuela 02010 Miles Aruba Netherlands Oranjestad^ Antilles Curaçao Venezuela he island of Aruba is located at 12°30' North and 70° West and lies about 32 km from the northern coast of Venezuela. It is the smallest and most western island of a group of three Dutch Leeward Islands, the “ABC islands” of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. T 2 Aruba is 31 km long and 8 km wide and encompasses an area of 180 km . GENERAL CONTEXT AND HEALTH traction of 2.4% is projected (Table 1). While Aruba has made DETERMINANTS considerable progress toward alleviating poverty, available data suggest that income inequality is still considerably larger than in Aruba’s capital is Oranjestad,and the island divides geograph- countries with comparable income levels. ically into eight districts: Noord/Tanki Leendert,Oranjestad-West, According to the Centrale Bank van Aruba, at the end of 2005, Oranjestad-East, Paradera, Santa Cruz, Savaneta, San Nicolas- inflation stood at 3.8%, compared to 2.8% a year earlier. Mea- North, and San Nicolas-South. The average temperature is 28°C sured as a 12-month average percentage change,the inflation rate with a cooling northeast tradewind. Rainfall averages about accelerated by nearly 1% to 3.4% in 2005, reflecting mainly price 500 mm a year, with October, November, December, and January increases for water, electricity, and gasoline following the rise in accounting for most of it. Aruba lies outside the hurricane belt oil prices on the international market. At the end of 2005, the and at most experiences only fringe effects of nearby heavy trop- overall economy continued to show an upward growth trend ical storms. -

The EU and Its Overseas Entities Joining Forces on Biodiversity and Climate Change

BEST The EU and its overseas entities Joining forces on biodiversity and climate change Photo 1 4.2” x 10.31” Position x: 8.74”, y: .18” Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Azores Madeira French Guadeloupe Canary Guiana Martinique islands Reunion Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Anguilla British Virgin Is. Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores Aruba Wallis Bonaire French & Futuna Caraçao Ascension Polynesia Mayotte BIOT (British Indian Ocean Ter.) St Helena Scattered New Islands Caledonia Pitcairn Tristan da Cunha Amsterdam St-Paul South Georgia Crozet Islands TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises) Iles Sandwich Falklands Kerguelen (Islas Malvinas) BAT (British Antarctic Territory) Adélie Land Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs) Anguilla The EU overseas dimension British Virgin Is. Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique Aruba French Guiana Wallis Bonaire French & Futuna Caraçao Ascension Polynesia Mayotte BIOT (British Indian Ocean Ter.) St Helena Reunion Scattered New Islands Caledonia Pitcairn Tristan da Cunha Amsterdam St-Paul South Georgia Crozet Islands TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises) Iles Sandwich Falklands Kerguelen (Islas Malvinas) BAT (British Antarctic Territory) Adélie Land ORs OCTs Anguilla The EU overseas dimension British Virgin Is. A major potential for cooperation on climate change and biodiversity Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. -

Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, Saba and the European Netherlands Conclusions

JOINED TOGETHER FOR FIVE YEARS BONAIRE, SINT EUSTATIUS, SABA AND THE EUROPEAN NETHERLANDS CONCLUSIONS Preface On 10 October 2010, Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba each became a public entitie within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In the run-up to this transition, it was agreed to evaluate the results of the new political structure after five years. Expectations were high at the start of the political change. Various objectives have been achieved in these past five years. The levels of health care and education have improved significantly. But there is a lot that is still disappointing. Not all expectations people had on 10 October 2010 have been met. The 'Committee for the evaluation of the constitutional structure of the Caribbean Netherlands' is aware that people have different expectations of the evaluation. There is some level of scepticism. Some people assume that the results of the evaluation will lead to yet another report, which will not have a considerable contribution to the, in their eyes, necessary change. Other people's expectations of the evaluation are high and they expect the results of the evaluation to lead to a new moment or a relaunch for further agreements that will mark the beginning of necessary changes. In any case, five years is too short a period to be able to give a final assessment of the new political structure. However, five years is an opportune period of time to be able to take stock of the situation and identify successes and elements that need improving. Add to this the fact that the results of the evaluation have been repeatedly identified as the cause for making new agreements. -

Peer Review Report Phase 2 Implementation of the Standard In

Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information GLOBAL FORUM ON TRANSPARENCY AND EXCHANGE for Tax Purposes OF INFORMATION FOR TAX PURPOSES PEER REVIEWS, PHASE 2: ARUBA This report contains a “Phase 2: Implementation of the Standards in Practice” review, as well as revised version of the “Phase 1: Legal and Regulatory Framework review” already released for this country. The Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes is the Peer Review Report multilateral framework within which work in the area of tax transparency and exchange of information is carried out by over 120 jurisdictions which participate in the work of the Phase 2 Global Forum on an equal footing. The Global Forum is charged with in-depth monitoring and peer review of the implementation Implementation of the Standard of the standards of transparency and exchange of information for tax purposes. These standards are primarily refl ected in the 2002 OECD Model Agreement on Exchange of in Practice Information on Tax Matters and its commentary, and in Article 26 of the OECD Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital and its commentary as updated in 2004, which has ARUBA been incorporated in the UN Model Tax Convention. Peer Review Report Phase 2 Implementation of the Standard in Practice The standards provide for international exchange on request of foreseeably relevant information for the administration or enforcement of the domestic tax laws of a requesting party. “Fishing expeditions” are not authorised, but all foreseeably relevant information must be provided, including bank information and information held by fi duciaries, regardless of the existence of a domestic tax interest or the application of a dual criminality standard.