Prehistoric Cultural Developments on Bonaire, Netherlands Antilles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

World Heritage Paper 14 ; Caribbean

PM_Caraïbe14_CD NEW me 13/07/05 16:09 Page 1 Présentation des pays de la Caraïbe et des protections légales Presentation of the Caribbean Annexes countries and legal protections Presentación de los países del Caribe y de las protecciones legales Les cultures préhispaniques des Caraïbes insulaires et les musées et sites associés à ces cultures (Lennox Honychurch) Page 3 Pre-Hispanic Cultures of the Insular Caribbean and Museums and Sites Page 21 Associated with these Cultures (Lennox Honychurch) 2 Bahamas (Gail Saunders) 3 Page 39 El patrimonio cultural del Parque Nacional del Este, República Dominicana (Adolfo López Belando) 4 Page 41 República Dominicana: las primeras fundaciones coloniales españolas de la isla de Santo Domingo (José Gabriel Atiles Bido) 5 Page 49 Archaeological Investigations in Saint Kitts and Nevis Page 55 (Larry Armony) 6 Guadeloupe: les Roches Gravées des Petites Antilles un patrimoine commun (Henri Petitjean Roget et Gérard Richard) 7 Page 59 Proposition de la Martinique pour des candidatures au Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO (Lyne-Rose Beuze) 8 Page 63 Aspects complémentaires pour une possible candidature de St. Pierre au Patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO (Benoît Bérard) 9 Page 69 Curaçao & Bonaire : Indian Rock Drawings 0 Page 73 (Lionel Janga) Aruba (Harold J.Kelly) Page 77 La législation française en archéologie Page 85 (Olivier Kayser) 2 Caribbean Area Rock Art Evaluation Project : Preparation for World Page 89 Heritage Site Nomination (Daniel Mattson) 3 El Patrimonio Arqueológico Aborigen Cubano: protección y -

Ix Viii the World by Income

The world by income Classified according to World Bank estimates of 2016 GNI per capita (current US dollars,Atlas method) Low income (less than $1,005) Greenland (Den.) Lower middle income ($1,006–$3,955) Upper middle income ($3,956–$12,235) Faroe Russian Federation Iceland Islands High income (more than $12,235) (Den.) Finland Norway Sweden No data Canada Netherlands Estonia Isle of Man (U.K.) Russian Latvia Denmark Fed. Lithuania Ireland U.K. Germany Poland Belarus Belgium Channel Islands (U.K.) Ukraine Kazakhstan Mongolia Luxembourg France Moldova Switzerland Romania Uzbekistan Dem.People’s Liechtenstein Bulgaria Georgia Kyrgyz Rep.of Korea United States Azer- Rep. Spain Monaco Armenia Japan Portugal Greece baijan Turkmenistan Tajikistan Rep.of Andorra Turkey Korea Gibraltar (U.K.) Syrian China Malta Cyprus Arab Afghanistan Tunisia Lebanon Rep. Iraq Islamic Rep. Bermuda Morocco Israel of Iran (U.K.) West Bank and Gaza Jordan Bhutan Kuwait Pakistan Nepal Algeria Libya Arab Rep. Bahrain The Bahamas Western Saudi Qatar Cayman Is. (U.K.) of Egypt Bangladesh Sahara Arabia United Arab India Hong Kong, SAR Cuba Turks and Caicos Is. (U.K.) Emirates Myanmar Mexico Lao Macao, SAR Haiti Cabo Mauritania Oman P.D.R. N. Mariana Islands (U.S.) Belize Jamaica Verde Mali Niger Thailand Vietnam Guatemala Honduras Senegal Chad Sudan Eritrea Rep. of Guam (U.S.) Yemen El Salvador The Burkina Cambodia Philippines Marshall Nicaragua Gambia Faso Djibouti Federated States Islands Guinea Benin Costa Rica Guyana Guinea- Brunei of Micronesia Bissau Ghana Nigeria Central Ethiopia Sri R.B. de Suriname Côte South Darussalam Panama Venezuela Sierra d’Ivoire African Lanka French Guiana (Fr.) Cameroon Republic Sudan Somalia Palau Colombia Leone Togo Malaysia Liberia Maldives Equatorial Guinea Uganda São Tomé and Príncipe Rep. -

1 UNESCO Regional Office for Culture in Latin America and the Caribbean Places of Memory for the Slave Route in the Latin Caribb

UNESCO Regional Office for Culture in Latin America and the Caribbean Places of Memory for the Slave Route in the Latin Caribbean Site Registration Form I- IDENTIFICATION: I-1: Entry: 002 I-2: Code: ABW.s.01 I-3: National Code: AT 081 I-4: Present name: Sport Hall ASU Santa Cruz site I-5: Historic name: - II- GENERAL INFORMATION: II-1: Location: II-1- a: Country: Aruba II-1- b: Province: II-1- c: Municipality: Santa Cruz II-2: Uses: II-2- a: Original use: Amerindian village centre II-2- b: Present use: fallow land II-3: Classification: II-4: Category of Protection: II-5: Function- testimony: Cultural Landscape (See IV-1) World Heritage Landing Port Cultural Route (See IV-2) Masterpiece Slave Market Population Settlement (See IV-3) Biosphere Reserve Place of confinement Agro-industrial compound (See IV-4) National Monument X Dwelling site Building (See IV-5) Local Monument Site of production X Site (See IV-6) X Other: Archeol. Museum Site AT081 Site of resistance II-6: The property is on the National Tentative List: Yes X No Refuge of maroons II-7: Accessibility: II-8: Ownership: Burial place X Accessible State Shipwreck Not easily accessible Private Religious-ceremonial site Inaccessible Mixed Route Other: Multipurpose II-8: Level of accessibility: X Free Restricted Exclusive III- INTANGIBLE CULTURAL MANIFESTATIONS ASSOCIATED TO THE PROPERTY: III-1: Characterization of the bearer community: Pre-Columbian Caquetio population. III-2: Type of intangible heritage manifestation: Oral traditions and expressions: Performing arts: X Social uses, rituals and festivities: X Knowledge and uses related to nature and the Universe: X Traditional crafts techniques: III-2-a: Describe the nature, periodicity and predominant characteristics of the manifestations at present: The proposed archaeological site is located in the center of the central pre-Columbian Caquetio village of Aruba. -

The Value of Nature in the Caribbean Netherlands

The Economics of Ecosystems The value of nature and Biodiversity in the Caribbean Netherlands in the Caribbean Netherlands 2 Total Economic Value in the Caribbean Netherlands The value of nature in the Caribbean Netherlands The Challenge Healthy ecosystems such as the forests on the hillsides of the Quill on St Eustatius and Saba’s Mt Scenery or the corals reefs of Bonaire are critical to the society of the Caribbean Netherlands. In the last decades, various local and global developments have resulted in serious threats to these fragile ecosystems, thereby jeopardizing the foundations of the islands’ economies. To make well-founded decisions that protect the natural environment on these beautiful tropical islands against the looming threats, it is crucial to understand how nature contributes to the economy and wellbeing in the Caribbean Netherlands. This study aims to determine the economic value and the societal importance of the main ecosystem services provided by the natural capital of Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba. The challenge of this project is to deliver insights that support decision-makers in the long-term management of the islands’ economies and natural environment. Overview Caribbean Netherlands The Caribbean Netherlands consist of three islands, Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba all located in the Caribbean Sea. Since 2010 each island is part of the Netherlands as a public entity. Bonaire is the largest island with 16,000 permanent residents, while only 4,000 people live in St Eustatius and approximately 2,000 in Saba. The total population of the Caribbean Netherlands is 22,000. All three islands are surrounded by living coral reefs and therefore attract many divers and snorkelers. -

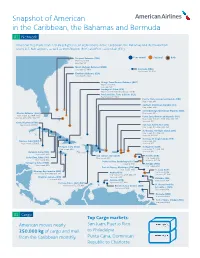

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network American flies more than 170 daily flights to 38 destinations in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda from seven U.S. hub airports, as well as from Boston (BOS) and Fort Lauderdale (FLL). Freeport, Bahamas (FPO) Year-round Seasonal Both Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Marsh Harbour, Bahamas (MHH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA Bermuda (BDA) Year-round: JFK, PHL Eleuthera, Bahamas (ELH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA George Town/Exuma, Bahamas (GGT) Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Santiago de Cuba (SCU) Year-round: MIA (Coming May 3, 2019) Providenciales, Turks & Caicos (PLS) Year-round: CLT, MIA Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic (POP) Year-round: MIA Santiago, Dominican Republic (STI) Year-round: MIA Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (SDQ) Nassau, Bahamas (NAS) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD Punta Cana, Dominican Republic (PUJ) Seasonal: DCA, DFW, LGA, PHL Year-round: BOS, CLT, DFW, MIA, ORD, PHL Seasonal: JFK Grand Cayman (GCM) Year-round: CLT, MIA San Juan, Puerto Rico (SJU) Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD, PHL St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands (STT) Year-round: CLT, MIA, SJU Seasonal: JFK, PHL St. Croix, US Virgin Islands (STX) Havana, Cuba (HAV) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA Seasonal: CLT Holguin, Cuba (HOG) St. Maarten (SXM) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, PHL Varadero, Cuba (VRA) Seasonal: JFK Year-round: MIA Cap-Haïtien, Haiti (CAP) St. Kitts (SKB) Santa Clara, Cuba (SNU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT, JFK Pointe-a-Pitre, Guadeloupe (PTP) Camagey, Cuba (CMW) Seasonal: MIA Antigua (ANU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Fort-de-France, Martinique (FDF) Year-round: MIA St. -

St. Lucia Earns Junior Chef Award at Taste Of

MEDIA CONTACTS: KTCpr Theresa M. Oakes / [email protected] Leigh-Mary Hoffmann / [email protected] Telephone: 516-594-4100 #1101 **high resolution images available** BAHAMAS WINS TEAM, BARTENDER, PASTRY TOP HONORS; PUERTO RICO TAKES CHEF CATEGORY; ST. LUCIA EARNS JUNIOR CHEF AWARD AT TASTE OF THE CARIBBEAN 2015 MIAMI, FL (June 15, 2015) – The Bahamas National Culinary Team won three of the five top categories at the Taste of the Caribbean culinary competition this past weekend earning honors as Caribbean National Team of the Year and individual honors to Marv Cunningham, Bahamas for Caribbean Bartender of the Year and four-time winner Sheldon Tracey Sweeting, Bahamas, for Caribbean Pastry Chef of the Year. Jonathan Hernandez, Puerto Rico was crowned Caribbean Chef of the Year and Edna Butcher, St. Lucia, was named Caribbean Junior Chef of the Year. "Congratulations to all of the Taste of the Caribbean participants, their national hotel associations, team managers and sponsors for developing 10 Caribbean national culinary teams to compete at our annual culinary event," said Frank Comito, director general and CEO of the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association (CHTA). "Your commitment to culinary excellence in our region is very much appreciated as we showcase the region’s culinary and beverage offerings. Congratulations to all of the winners for a job well-done," Comito added. Presented by CHTA, Taste of the Caribbean featured cooking and bartending competitions between 10 Caribbean culinary teams from Anguilla, Bahamas, Barbados, Bonaire, British Virgin Islands, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Lucia, Suriname and the U.S. Virgin Islands with the winners being named the "best of the best" throughout the region. -

Constraints on Structual Borrowing in a Multilingual Contact Situation

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons IRCS Technical Reports Series Institute for Research in Cognitive Science 5-1-2005 Constraints on Structual Borrowing in a Multilingual Contact Situation Tara S. Sanchez University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports Part of the Linguistics Commons Sanchez, Tara S., "Constraints on Structual Borrowing in a Multilingual Contact Situation" (2005). IRCS Technical Reports Series. 4. https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports/4 University of Pennsylvania Institute for Research in Cognitive Science Technical Report No. IRCS-05-01 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ircs_reports/4 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Constraints on Structual Borrowing in a Multilingual Contact Situation Abstract Many principles of structural borrowing have been proposed, all under qualitative theories. Some argue that linguistic conditions must be met for borrowing to occur (‘universals’); others argue that aspects of the socio-demographic situation are more relevant than linguistic considerations (e.g. Thomason and Kaufman 1988). This dissertation evaluates the roles of both linguistic and social factors in structural borrowing from a quantitative, variationist perspective via a diachronic and ethnographic examination of the language contact situation on Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao, where the berian creole, Papiamentu, is in contact with Spanish, Dutch, and English. Data are fro m texts (n=171) and sociolinguistic interviews (n=129). The progressive, the passive construction, and focus fronting are examined. In addition, variationist methods were applied in a novel way to the system of verbal morphology. The degree to which borrowed morphemes are integrated into Papiamentu was noted at several samplings over a 100-year time span. -

The European Union, Its Overseas Territories and Non-Proliferation: the Case of Arctic Yellowcake

eU NoN-ProliferatioN CoNsortiUm The European network of independent non-proliferation think tanks NoN-ProliferatioN PaPers No. 25 January 2013 THE EUROPEAN UNION, ITS OVERSEAS TERRITORIES AND NON-PROLIFERATION: THE CASE OF ARCTIC YELLOWCAKE cindy vestergaard I. INTRODUCTION SUMMARY There are 26 countries and territories—mainly The European Union (EU) Strategy against Proliferation of small islands—outside of mainland Europe that Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD Strategy) has been have constitutional ties with a European Union applied unevenly across EU third-party arrangements, (EU) member state—either Denmark, France, the hampering the EU’s ability to mainstream its non- proliferation policies within and outside of its borders. Netherlands or the United Kingdom.1 Historically, This inconsistency is visible in the EU’s current approach since the establishment of the Communities in 1957, to modernizing the framework for association with its the EU’s relations with these overseas countries and overseas countries and territories (OCTs). territories (OCTs) have focused on classic development The EU–OCT relationship is shifting as these islands needs. However, the approach has been changing over grapple with climate change and a drive toward sustainable the past decade to a principle of partnership focused and inclusive development within a globalized economy. on sustainable development and global issues such While they are not considered islands of proliferation as poverty eradication, climate change, democracy, concern, effective non-proliferation has yet to make it to human rights and good governance. Nevertheless, their shores. Including EU non-proliferation principles is this new and enhanced partnership has yet to address therefore a necessary component of modernizing the EU– the EU’s non-proliferation principles and objectives OCT relationship. -

The EU and Its Overseas Entities Joining Forces on Biodiversity and Climate Change

BEST The EU and its overseas entities Joining forces on biodiversity and climate change Photo 1 4.2” x 10.31” Position x: 8.74”, y: .18” Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Azores Madeira French Guadeloupe Canary Guiana Martinique islands Reunion Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique French Guiana Reunion Outermost Regions (ORs) Anguilla British Virgin Is. Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores Aruba Wallis Bonaire French & Futuna Caraçao Ascension Polynesia Mayotte BIOT (British Indian Ocean Ter.) St Helena Scattered New Islands Caledonia Pitcairn Tristan da Cunha Amsterdam St-Paul South Georgia Crozet Islands TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises) Iles Sandwich Falklands Kerguelen (Islas Malvinas) BAT (British Antarctic Territory) Adélie Land Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs) Anguilla The EU overseas dimension British Virgin Is. Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. Guadeloupe Canary islands Martinique Aruba French Guiana Wallis Bonaire French & Futuna Caraçao Ascension Polynesia Mayotte BIOT (British Indian Ocean Ter.) St Helena Reunion Scattered New Islands Caledonia Pitcairn Tristan da Cunha Amsterdam St-Paul South Georgia Crozet Islands TAAF (Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises) Iles Sandwich Falklands Kerguelen (Islas Malvinas) BAT (British Antarctic Territory) Adélie Land ORs OCTs Anguilla The EU overseas dimension British Virgin Is. A major potential for cooperation on climate change and biodiversity Turks & Caïcos Caïman Islands Montserrat Sint-Marteen Sint-Eustatius Greenland Saba St Pierre & Miquelon Azores St-Martin Madeira St-Barth. -

Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, Saba and the European Netherlands Conclusions

JOINED TOGETHER FOR FIVE YEARS BONAIRE, SINT EUSTATIUS, SABA AND THE EUROPEAN NETHERLANDS CONCLUSIONS Preface On 10 October 2010, Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba each became a public entitie within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In the run-up to this transition, it was agreed to evaluate the results of the new political structure after five years. Expectations were high at the start of the political change. Various objectives have been achieved in these past five years. The levels of health care and education have improved significantly. But there is a lot that is still disappointing. Not all expectations people had on 10 October 2010 have been met. The 'Committee for the evaluation of the constitutional structure of the Caribbean Netherlands' is aware that people have different expectations of the evaluation. There is some level of scepticism. Some people assume that the results of the evaluation will lead to yet another report, which will not have a considerable contribution to the, in their eyes, necessary change. Other people's expectations of the evaluation are high and they expect the results of the evaluation to lead to a new moment or a relaunch for further agreements that will mark the beginning of necessary changes. In any case, five years is too short a period to be able to give a final assessment of the new political structure. However, five years is an opportune period of time to be able to take stock of the situation and identify successes and elements that need improving. Add to this the fact that the results of the evaluation have been repeatedly identified as the cause for making new agreements. -

The African Telatelist

The African Telatelist Newsletter 189 of the African Telately Association – March 2014. ___________________________________________________________________________ Bonaire (C.Edwards) Bonaire (/bɒ ˈ nɛ ər/; Dutch: Bonaire, Papiament u: Boneiru) is a Caribbean island that, with the uninhabited islet of Klein Bonaire nestled in its western crescent, forms a special municipality (officially public body) of the Netherlands. Together with Aruba and Curaçao it forms a group referred to as the ABC islands of the Leeward Antilles, the southern island chain of the Lesser Antilles. The name Bonaire is thought to have originally come from the Caquetio word 'Bonay'. The early Spanish and Dutch modified its spelling to Bojnaj and also Bonaire, which means "Good Air". Coat of Arms Bonaire's capital is Kralendijk. Original inhabitants Bonaire's earliest known inhabitants were the Caquetio Indians, a branch of the Arawak who came by canoe from Venezuela in about 1000 CE. Archeological remains of Caquetio culture have been found at certain sites northeast of Kralendijk and near Lac Bay. Caquetio rock paintings and Location of Bonaire (circled in Red) petroglyphs have been preserved in caves at Spelonk, Onima, Ceru Pungi, and Ceru Crita- Coordinates: 12°9′N 68°16′W Cabai. The Caquetios were apparently a very tall people, for the Spanish name for the ABC Bonaire was part of the Netherlands Antilles until Islands was 'las Islas de los Gigantes' or 'the the country's dissolution on 10 October islands of the giants. 2010, when the island (including Klein Bonaire) became a special municipality within the country European arrival of the Netherlands. In 1499, Alonso de Ojeda arrived in Curaçao and a neighbouring island that was almost certainly Bonaire.