Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, Saba and the European Netherlands Conclusions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Eustatius (Statia)

St. Eustatius (Statia) Overview: Sint Eustatius, also known as Statia, is one of the islands which make up the Netherlands Antilles. Over its long history, it changed hands more than 20 times. The island has remained in Dutch hands since 1816. Vocanic in origin, and quite rugged along the coastal areas, it was once one of the busiest and most powerful commercial ports in the Caribbean. As a result of the British blockade during America's Revolutionary War, most goods destined for the new colonies flowed into St. Eustatius. It was not uncommon to see hundreds of supply ships off Oranjestad. When that war ended and mail and supplies were sent directly to the new United States, the economy of St. Eustatius changed dramatically. According to tradition, it was the first foreign port to salute (1776) the American flag. Tourism is the major industry today, and the island is a favorite destination for scuba diving aficionados and nature lovers. Territory: Highest point = Mt. Mazinga, 1,968 ft. (602m) St. Eustatius is hilly with a central flat plain. Sandy beaches are rare. Geographically, the island is saddle- shaped, with the 602 meter-high Mount Mazinga, colloquially called the Quill (a dormant volcano) to the southeast and the smaller pair Signal Hill/Little Mountain and Boven Mountain to the northwest. The bulk of the island's population lives in the "dip" between the two areas, which crosses the center of the island. The island is just 5 miles long and 2 miles wide; area: 21 sq. km. Location: It is in the northern, Leeward Islands portion of the West Indies, some distance southeast of the Virgin Islands. -

State of Nature in the Dutch Caribbean: Saba and the Saba Bank

State of Nature in the Dutch Caribbean: Saba and the Saba Bank Open sea and deep sea (EEZ) Figure 1: Habitats of Saba (Verweij & Mücher, 2018) Wageningen Research recently published fields underwater, Saba is rich with a variety an alarming report on the state of nature of different habitats. Unfortunately, the for the three Dutch Caribbean islands recent Wageningen Research report shows (Bonaire, Saba and St. Eustatius), com- that many of these areas, both above missioned by the Ministry of Agriculture, and below water, are showing signs of Nature and Food Quality. All 33 experts degradation. that worked on this report concluded that the “Conservation status 1 of the Governments are beginning to understand biodiversity in the Caribbean Netherlands that managing nature goes beyond just is assessed as moderately unfavorable to protecting natural assets, but can also very unfavorable”. help promote positive economic growth (Ministry of Economic Affairs, 2013). Saba and St. Eustatius are two special mu- Protecting the environment means pro- nicipalities which make up the Caribbean tecting the services they provide such as Netherlands leeward islands. Saba con- natural coastal protection and recreational sists of the main island, Saba, and a large use for locals and tourists (de Knegt, 2014). submerged carbonate platform, the Saba TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Bank. The Saba Bank is the largest national Biodiversity) recently valued the annual park in the Kingdom of the Netherlands total economic value of nature on Saba at (Saba Bank: 268.000 hectares; Wadden 28.4 million USD (Cado van der Lely et al., Sea 240.000 hectares), and has some of the 2014). -

Plum Piece Evidence for Archaic Seasonal Occupation on Saba, Northern Lesser Antilles Around 3300 BP Corinne L

Journal of Caribbean Archaeology Copyright 2003 ISSN 1524-4776 Plum Piece Evidence for Archaic Seasonal Occupation on Saba, Northern Lesser Antilles around 3300 BP Corinne L. Hofman Menno L.P. Hoogland Recent investigations on the island of Saba, northern Lesser Antilles, revealed evidence of preceramic occupation in the northwestern part of the island at an elevation of approxinately 400 m above sea level. The inland location of dense midden deposits in a tropical forest environment makes the Plum Piece site unique for studying the preceramic occupation of the Antilles, a period that is otherwise mainly known from coastal settings. The recovered artifacts and the radiocarbon dates support an attribution to the Archaic period of the preceramic Age. The nature of the tools and the restricted number of exploited food sources suggest a temporary, probably seasonal, occupation of the site for a unique activity. _____________________________________ Archaeological investigations on the island coastal exploitation in which shellfish of Saba, northern Lesser Antilles (Figure 1) predominates. The species collected are related during the summers of 2001 and 2002 revealed to the exploitation of specific coastal evidence of preceramic occupation at the site of environments, varying from mangroves to Plum Piece in the northwestern part of the island shallow-water and shallow-reef habitats. dating from approximately 3300 BP. Prior to these investigations a preceramic date of 3155± The atypical location of the site of Plum 65 BP had been obtained from the Fort Bay area Piece in the tropical forest area of Saba at an in the northeastern sector of Saba (Roobol and elevation of 400 m above sea level provides Smith 1980). -

(OECD) 2018 Progress Report on Preferential Regimes Has Found the Curaçao Tax Regimes Not to Be Harmful

Newsflash OECD report on Curaçao tax regimes The Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) 2018 Progress Report on Preferential Regimes has found the Curaçao tax regimes not to be harmful. The OECD released a new publication on January 29, 2019, called “Harmful Tax Practices - 2018 Progress Report on Preferential Regimes”. The results show that jurisdictions have delivered on their commitment to comply with the standard on harmful tax practices, including their guarantee that preferential regimes align taxation with substance. The 2018 Progress Report on Preferential Regimes contains new conclusions on 57 regimes based on the assessment of preferential tax regimes comprising more than 120 member jurisdictions of the Inclusive Framework. Curaçao tax regimes Curaçao has amended three preferential regimes considered to be harmful (the exempt company regime, the export facility and the economic zone), and it has introduced the innovation box regime. The Forum on Harmful Tax Practices (FHTP) has assessed the amendments and the conclusion was as follows: the Curaçao Investment Company is not harmful, the innovation box is not harmful, the economic zone is out of scope, and the export regime has been abolished. The Curaçao Investment Company The exempt company has been replaced with the Curaçao Investment Company, which has been assessed to be “not harmful”. This means amendments have been taken into account to ensure the removal of harmful features. The report also mentions that substance requirements are in place and that no grandfathering is provided. The Innovation Box Regime The Innovation Box Regime was designed in compliance with FHTP standards and has been assessed to be “not harmful”. -

Ix Viii the World by Income

The world by income Classified according to World Bank estimates of 2016 GNI per capita (current US dollars,Atlas method) Low income (less than $1,005) Greenland (Den.) Lower middle income ($1,006–$3,955) Upper middle income ($3,956–$12,235) Faroe Russian Federation Iceland Islands High income (more than $12,235) (Den.) Finland Norway Sweden No data Canada Netherlands Estonia Isle of Man (U.K.) Russian Latvia Denmark Fed. Lithuania Ireland U.K. Germany Poland Belarus Belgium Channel Islands (U.K.) Ukraine Kazakhstan Mongolia Luxembourg France Moldova Switzerland Romania Uzbekistan Dem.People’s Liechtenstein Bulgaria Georgia Kyrgyz Rep.of Korea United States Azer- Rep. Spain Monaco Armenia Japan Portugal Greece baijan Turkmenistan Tajikistan Rep.of Andorra Turkey Korea Gibraltar (U.K.) Syrian China Malta Cyprus Arab Afghanistan Tunisia Lebanon Rep. Iraq Islamic Rep. Bermuda Morocco Israel of Iran (U.K.) West Bank and Gaza Jordan Bhutan Kuwait Pakistan Nepal Algeria Libya Arab Rep. Bahrain The Bahamas Western Saudi Qatar Cayman Is. (U.K.) of Egypt Bangladesh Sahara Arabia United Arab India Hong Kong, SAR Cuba Turks and Caicos Is. (U.K.) Emirates Myanmar Mexico Lao Macao, SAR Haiti Cabo Mauritania Oman P.D.R. N. Mariana Islands (U.S.) Belize Jamaica Verde Mali Niger Thailand Vietnam Guatemala Honduras Senegal Chad Sudan Eritrea Rep. of Guam (U.S.) Yemen El Salvador The Burkina Cambodia Philippines Marshall Nicaragua Gambia Faso Djibouti Federated States Islands Guinea Benin Costa Rica Guyana Guinea- Brunei of Micronesia Bissau Ghana Nigeria Central Ethiopia Sri R.B. de Suriname Côte South Darussalam Panama Venezuela Sierra d’Ivoire African Lanka French Guiana (Fr.) Cameroon Republic Sudan Somalia Palau Colombia Leone Togo Malaysia Liberia Maldives Equatorial Guinea Uganda São Tomé and Príncipe Rep. -

The Value of Nature in the Caribbean Netherlands

The Economics of Ecosystems The value of nature and Biodiversity in the Caribbean Netherlands in the Caribbean Netherlands 2 Total Economic Value in the Caribbean Netherlands The value of nature in the Caribbean Netherlands The Challenge Healthy ecosystems such as the forests on the hillsides of the Quill on St Eustatius and Saba’s Mt Scenery or the corals reefs of Bonaire are critical to the society of the Caribbean Netherlands. In the last decades, various local and global developments have resulted in serious threats to these fragile ecosystems, thereby jeopardizing the foundations of the islands’ economies. To make well-founded decisions that protect the natural environment on these beautiful tropical islands against the looming threats, it is crucial to understand how nature contributes to the economy and wellbeing in the Caribbean Netherlands. This study aims to determine the economic value and the societal importance of the main ecosystem services provided by the natural capital of Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba. The challenge of this project is to deliver insights that support decision-makers in the long-term management of the islands’ economies and natural environment. Overview Caribbean Netherlands The Caribbean Netherlands consist of three islands, Bonaire, St Eustatius and Saba all located in the Caribbean Sea. Since 2010 each island is part of the Netherlands as a public entity. Bonaire is the largest island with 16,000 permanent residents, while only 4,000 people live in St Eustatius and approximately 2,000 in Saba. The total population of the Caribbean Netherlands is 22,000. All three islands are surrounded by living coral reefs and therefore attract many divers and snorkelers. -

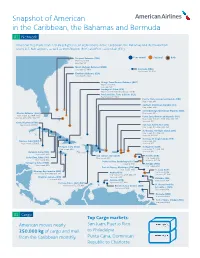

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network American flies more than 170 daily flights to 38 destinations in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda from seven U.S. hub airports, as well as from Boston (BOS) and Fort Lauderdale (FLL). Freeport, Bahamas (FPO) Year-round Seasonal Both Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Marsh Harbour, Bahamas (MHH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA Bermuda (BDA) Year-round: JFK, PHL Eleuthera, Bahamas (ELH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA George Town/Exuma, Bahamas (GGT) Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Santiago de Cuba (SCU) Year-round: MIA (Coming May 3, 2019) Providenciales, Turks & Caicos (PLS) Year-round: CLT, MIA Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic (POP) Year-round: MIA Santiago, Dominican Republic (STI) Year-round: MIA Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (SDQ) Nassau, Bahamas (NAS) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD Punta Cana, Dominican Republic (PUJ) Seasonal: DCA, DFW, LGA, PHL Year-round: BOS, CLT, DFW, MIA, ORD, PHL Seasonal: JFK Grand Cayman (GCM) Year-round: CLT, MIA San Juan, Puerto Rico (SJU) Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD, PHL St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands (STT) Year-round: CLT, MIA, SJU Seasonal: JFK, PHL St. Croix, US Virgin Islands (STX) Havana, Cuba (HAV) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA Seasonal: CLT Holguin, Cuba (HOG) St. Maarten (SXM) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, PHL Varadero, Cuba (VRA) Seasonal: JFK Year-round: MIA Cap-Haïtien, Haiti (CAP) St. Kitts (SKB) Santa Clara, Cuba (SNU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT, JFK Pointe-a-Pitre, Guadeloupe (PTP) Camagey, Cuba (CMW) Seasonal: MIA Antigua (ANU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Fort-de-France, Martinique (FDF) Year-round: MIA St. -

St. Lucia Earns Junior Chef Award at Taste Of

MEDIA CONTACTS: KTCpr Theresa M. Oakes / [email protected] Leigh-Mary Hoffmann / [email protected] Telephone: 516-594-4100 #1101 **high resolution images available** BAHAMAS WINS TEAM, BARTENDER, PASTRY TOP HONORS; PUERTO RICO TAKES CHEF CATEGORY; ST. LUCIA EARNS JUNIOR CHEF AWARD AT TASTE OF THE CARIBBEAN 2015 MIAMI, FL (June 15, 2015) – The Bahamas National Culinary Team won three of the five top categories at the Taste of the Caribbean culinary competition this past weekend earning honors as Caribbean National Team of the Year and individual honors to Marv Cunningham, Bahamas for Caribbean Bartender of the Year and four-time winner Sheldon Tracey Sweeting, Bahamas, for Caribbean Pastry Chef of the Year. Jonathan Hernandez, Puerto Rico was crowned Caribbean Chef of the Year and Edna Butcher, St. Lucia, was named Caribbean Junior Chef of the Year. "Congratulations to all of the Taste of the Caribbean participants, their national hotel associations, team managers and sponsors for developing 10 Caribbean national culinary teams to compete at our annual culinary event," said Frank Comito, director general and CEO of the Caribbean Hotel and Tourism Association (CHTA). "Your commitment to culinary excellence in our region is very much appreciated as we showcase the region’s culinary and beverage offerings. Congratulations to all of the winners for a job well-done," Comito added. Presented by CHTA, Taste of the Caribbean featured cooking and bartending competitions between 10 Caribbean culinary teams from Anguilla, Bahamas, Barbados, Bonaire, British Virgin Islands, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Lucia, Suriname and the U.S. Virgin Islands with the winners being named the "best of the best" throughout the region. -

Preliminary Checklist of Extant Endemic Species and Subspecies of the Windward Dutch Caribbean (St

Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos, P.A.J. Bakker, R.J.H.G. Henkens, J. A. de Freitas, A.O. Debrot Wageningen University & Research rapport C067/18 Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos1, P.A.J. Bakker2, R.J.H.G. Henkens3, J. A. de Freitas4, A.O. Debrot1 1. Wageningen Marine Research 2. Naturalis Biodiversity Center 3. Wageningen Environmental Research 4. Carmabi Publication date: 18 October 2018 This research project was carried out by Wageningen Marine Research at the request of and with funding from the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality for the purposes of Policy Support Research Theme ‘Caribbean Netherlands' (project no. BO-43-021.04-012). Wageningen Marine Research Den Helder, October 2018 CONFIDENTIAL no Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Bos OG, Bakker PAJ, Henkens RJHG, De Freitas JA, Debrot AO (2018). Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species of St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and Saba Bank. Wageningen, Wageningen Marine Research (University & Research centre), Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Keywords: endemic species, Caribbean, Saba, Saint Eustatius, Saint Marten, Saba Bank Cover photo: endemic Anolis schwartzi in de Quill crater, St Eustatius (photo: A.O. Debrot) Date: 18 th of October 2018 Client: Ministry of LNV Attn.: H. Haanstra PO Box 20401 2500 EK The Hague The Netherlands BAS code BO-43-021.04-012 (KD-2018-055) This report can be downloaded for free from https://doi.org/10.18174/460388 Wageningen Marine Research provides no printed copies of reports Wageningen Marine Research is ISO 9001:2008 certified. -

Ocha-Rolac-Caribbeanoverview-20200622.Pdf (English)

THE CARIBBEAN General overview As of March 2019 MONTSERRAT BAHAMAS BAHAMAS 16 15 18 8 BIRD ISLAND Independent CARICOM CDEMA UN Resident 2 CUBA 1 states members Participating StateTURKSs AND CAICOS ISLCooANDSrdinators 3 5 CAYMAN ISLANDS CUBA HAIDOMINICANTI REPUBLIC BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS NAVASSA ISLTURKSAND AND CAICOS ISLANDS MEXICO JAMAICA PUERTO RICO ANGUILLA UNITED STATES VIRGIN ISLANDS BELIZE SAINT KITTS AND NEVISANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 15 5 4 25 MONTSERRAT Territories CARICOM associate Countries and territories GUADELOUPE UNITEDGUA TESTMAATESLA OF AMERICA CDEMA BIRD ISLAND 4 members covered by RCs DOMINICA HONDURAS sub-hubs MARTINIQUE EL SALVADOR SAINT LUCIA SAINT VINCENT AND THE GRENADINESBARBADOS NICARAGUA ARUBA CGENERALAYMAN ISLANDS INFORMATION CURBOANÇAIRE,AO SINT EUSTATIUSIndependent AND SABAGRENADA Income levels: High Middle Low HAITI DOMINICAN REPUBLIC ARUBA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BERMUDA TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO BRITISH VIRGIN ISL. 1 COSTA RICA NAVASSA ISLAND 5 ANGUILLA 3 JAMBAAICAHAMAS CURAÇAO BONAIRE PUERTO RICO ST. MARTIN PANAMA ST. MAARTEN U.S. VIRGIN ANTIGUA AND VENEZUELA ISLANDS BARBUDA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA TURKS AND CAICOS ISLANDS GUYANA ST. KITTS AND NEVIS BELIZE TURKS AND CAICOS ISLANDS BAHAMAS COLOMBIA GUADELOUPE CUBA 4 SURINAME MONTSERRAT BAHAMAS BRAZIL DOMINICA ECUADOR CUBA TURKS AND CAICOS ISLANDS MARTINIQUE CAYMAN ISLANDS SAINT LUCIA CAYMAN ISLANDS HAITI CUBA HAIDOMINICANTI REPUBLIC BRDOMINICANITISH VIRGIN IS REPUBLICLANDS SAINT VINCENT NAVASSA ISLTURKSAND AND CAICOS ISLANDS MEXICO JAMAICA PUERTO RICO ANGUILLA AND -

The European Union, Its Overseas Territories and Non-Proliferation: the Case of Arctic Yellowcake

eU NoN-ProliferatioN CoNsortiUm The European network of independent non-proliferation think tanks NoN-ProliferatioN PaPers No. 25 January 2013 THE EUROPEAN UNION, ITS OVERSEAS TERRITORIES AND NON-PROLIFERATION: THE CASE OF ARCTIC YELLOWCAKE cindy vestergaard I. INTRODUCTION SUMMARY There are 26 countries and territories—mainly The European Union (EU) Strategy against Proliferation of small islands—outside of mainland Europe that Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD Strategy) has been have constitutional ties with a European Union applied unevenly across EU third-party arrangements, (EU) member state—either Denmark, France, the hampering the EU’s ability to mainstream its non- proliferation policies within and outside of its borders. Netherlands or the United Kingdom.1 Historically, This inconsistency is visible in the EU’s current approach since the establishment of the Communities in 1957, to modernizing the framework for association with its the EU’s relations with these overseas countries and overseas countries and territories (OCTs). territories (OCTs) have focused on classic development The EU–OCT relationship is shifting as these islands needs. However, the approach has been changing over grapple with climate change and a drive toward sustainable the past decade to a principle of partnership focused and inclusive development within a globalized economy. on sustainable development and global issues such While they are not considered islands of proliferation as poverty eradication, climate change, democracy, concern, effective non-proliferation has yet to make it to human rights and good governance. Nevertheless, their shores. Including EU non-proliferation principles is this new and enhanced partnership has yet to address therefore a necessary component of modernizing the EU– the EU’s non-proliferation principles and objectives OCT relationship. -

St.!Eustatius! Children’S!Rights!In!The!Caribbean!Netherlands! Karin!Kloosterboer! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! May!2013! ! !

Child on Sint Eustatius Children’s rights in the Caribbean Netherlands Karin Kloosterboer ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Child!on!St.!Eustatius! Children’s!rights!in!the!Caribbean!Netherlands! Karin!Kloosterboer! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! May!2013! ! ! ! ! Foreword! You!have!before!you!Child&on&St.&Eustatius.&Children’s&rights&in&the&Caribbean&Netherlands:! a!UNICEF!study!into!the!situation!of!children!growing!up!on!the!tropical!island!of!St.! Eustatius,!and!one!that!is!innovating!and!exceptional!for!several!reasons.! ! This!study!is!the!first!to!shed!light!on!all!aspects!of!the!lives!of!children!in!the!Caribbean! Netherlands.!!Child&on&St.&Eustatius!outlines!the!correlations!between!various!factors:! family!situation,!education,!health!and!health!care,!safety,!leisure!time,!participation,! housing!conditions,!and!financial!situation.!Alongside!this!report,!there!are!also!separate! reports!about!Saba!and!Bonaire.! ! ! This!is!also!a!pioneering!study!in!that!it!actually!surveyed!the!people!who!are!at!stake:!the! children!who!grow!up!on!the!islands.!Other!than!that,!the!study!also!drew!heavily!on!input! from!numerous!experts!who!play!a!role!in!children’s!lives!on!the!islands.!The!hearts!and! minds!of!these!–!often!inspired!–!professionals!contain!a!huge!wealth!of!information! about!both!children’s!lives!and!possibilities!for!improvement!of!their!lives.! ! This!study!paints!a!detailed!picture!that!the!researchers!have!subsequently!assessed! based!on!the!United!Nations!Convention!on!the!Rights!of!the!Child.!After!ratifying!this!