Sustainable Queensland Volume 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submission to Infrastructure Australia and Believes That the National Network Links in Queensland Need to Be Upgraded to Four-Star Ausrap Status

RACQ SUBMISSION TO INFRASTRUCTURE AUSTRALIA This submission covers: Issues Paper 1 - Australia’s Future Infrastructure Requirements; and Issues Paper 2 – Public Private Partnerships. The Royal Automobile Club of Queensland Limited October 2008 Page 1 of 16 20/10/2008 Summary The RACQ congratulates the Australian Government on the initiative to establish Infrastructure Australia and the undertaking to develop a long-range plan that prioritises infrastructure requirements based on transparent and objective criteria. The intention to establish nationally consistent Public Private Partnership (PPP) guidelines will also reduce bidding costs and encourage competition in the market. With the high cost of infrastructure, congestion, safety and environmental impacts, it is important that sound policy and project decisions are made. These need to move beyond the current electoral cycle and the debate between roads and public transport, toward a long term vision of a sustainable, integrated and resilient transport system that meets all future needs. This submission provides comments on policy issues associated with the funding of roads and details the five priority projects that RACQ believes should be implemented by Infrastructure Australia. These include: 1. Cooroy to Curra Bruce Highway deviation 2. Toowoomba Bypass 3. North West Motorway 4. Brisbane Rail Upgrade 5. Four-star National Network in Queensland Introduction Representing almost 1.2 million Queensland motorists, the RACQ congratulates the Australian Government on the initiative to establish Infrastructure Australia and the undertaking to develop a long-range plan that prioritises infrastructure requirements based on transparent and objective criteria. The intention to establish nationally consistent Public Private Partnership (PPP) guidelines will also reduce bidding costs and encourage competition in the market. -

Chapter 11 June 10

Department of Transport and Main Roads Fauna Sensitive Road Design Manual Technical Document Volume 2: Preferred Practices 11. TERMINOLOGY AND ABBREVIATIONS A..........................................................................................................................................1 B..........................................................................................................................................2 C..........................................................................................................................................2 D..........................................................................................................................................3 E ..........................................................................................................................................4 F ..........................................................................................................................................5 G..........................................................................................................................................5 H..........................................................................................................................................6 I ...........................................................................................................................................6 J ..........................................................................................................................................6 -

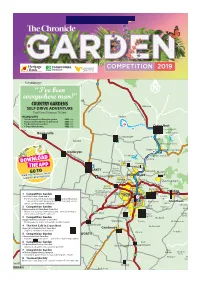

I've Been Everywhere Man!

es ltop Cr Hil Sk yline D r 85 Y A Mount G AND HIGHW y St o ynoch ombungee Rd K oundar B W ENGL NE A3 M c S h a n e Ballard D Mount r er Morris Rd z an Kynoch G d St edfor B Ganzers Rd Hermitage Rd Hermitage Rd Hermitage Rd es St op Cr y St Hillt attle Cranley w Goombungee Rd inch Rd Sk oundar n ee yline D B Gr r gent P u N 85 85 ys Ct t Bedwell St er e Ct Gleeson Cr es r eb illiam Ct v cle Y Kelly St W A ho Mc P er St Lila D y r ophia C ophia Burnview Ave Walsh St w Ryans Dr S es D yle St o T Mount Coonan St D G or St AND HIGHW e y St ch o Kyno ombungee Rd v Ella Ct Mor e A r ounda t St yc alim St B C o W ENGL Binda Dr B St Willo NE w A ve v oll A attle e Nic A3 w M P c rinc r S h n ee Ballard Alpine Ct a Mount n e St r G Gregory St Hhal St e D r derick D Hogg St Hogg St Ro Kynoch er Morris Rd Hendy St Seppelt St Perry St z an Felix St Chopin St r G air St d St Cotswold F J ohn Ct t St edfor an St Mabel St Pedersen St B r o Jonathan St r Hermitage Rd P Ganzers Rd Mor unc old Hills D Hermitage Rd Hermitage Rd Hills D Montana St Holb Kate St Mount St t St otsw r Cranley er St David St C y St Lofty D Hamzah er Bingar Katim Ct attle arr ossan St r T w F anda D Go t alinga St ir ombungeeon RdSt inch Rd M oundar een al St B r a St Macr r Abif St G ine D Hawk St wnlands at Ct y St gent P W e St Do y St estiv et St F u N 85 aminer D or St inch Rd r ollege eac gandy St C eah T T Mar P L c Mus Civil Ct y Ct Sherr Clar ys Ct t Bedwell St Barlow St Bur y St r e tin St e Ct Makepeace St gent P r Gleeson Cr ent es Mole St r v eb illiam Ct Maureen -

I. Financial Arrangements of the Project

12/10/2019 Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 To the Committee Secretary, Re: The Management of the Inland Rail project by the Australian Rail Track Corporation and The Commonwealth Government I am the President of the Inner Downs Inland Rail Action Group. Our group represents property owners located on the Inner Downs. Our goal is to bring about awareness of Inland Rail and to have the Inland Rail re-routed to a line that has less impact on community, prime farming land and the environment. I. Financial arrangements of the project The costing for the Inland Rail project is flawed because it has been calculated utilising outdated data, former route selection and construction design. The false business plan is flawed with financial inaccuracies including freight types and charges, not to mention 24 hour service agreement. Treating this project as an equity injection is not sustainable. The contingency percent was not included in the total costing for the project. There will be serious cost blowouts in most sections of the project which is reinforced by Ernest and Young stating that the Inland Rail Project would cost $16 000 000 000. The design and engineering of the Inland Rail project has been modified due to the complexity of the terrain. Most citizens would consider costing to then be revised, unlike ARTC. The organizations’ employees have reported on numerous occasions that it still is within budget parameters. It is not surprising that landowners are skeptical of the response. -

Chapter 5: Road Infrastructure

5 Road Infrastructure 5.1 A substantial proportion of AusLink funding is being applied to the improvement of Australia’s main road networks. In this chapter the Committee examines road connections, in areas other than port precincts, brought to its attention during this inquiry – either in evidence or during site visits – where funding of road improvements was demonstrated to be a priority. 5.2 As with rail links in the last Chapter, where the road issues relate directly to a port, they have been dealt with in Chapter 3. 5.3 It is obviously vital for the main highways to be brought up to an acceptable international standard. However, the Committee received evidence from a wide range of sources indicating that there are bottlenecks and “missing links” in other parts of the freight transport system, that are holding back its overall expansion and efficiency. 5.4 In many areas, the infrastructure needed is a section of road that is not covered by either funding from the AusLink program, or by State government funding. The chapter highlights some of these areas, where a project would make a marked difference to the efficiency, and/or safety, of the freight network and, in some instances, the GDP of a region. 5.5 This Chapter also refers to some problems of inconsistency between states and territories and the regulations they apply to freight transport by road. 134 Road Weight Limits 5.6 The question of increasing allowable road weight limits and axle loadings was raised by a number of participants in the inquiry. The difficulties caused by varying regulations between states were also raised. -

Darling Downs Regional Recovery Action Plan

DARLING DOWNS REGIONAL RECOVERY ACTION PLAN A MESSAGE FROM The Queensland Government has committed more THE PREMIER THE HONOURABLE ANNASTACIA PALASZCZUK MP than $8 billion to support COVID-19 health and AND economic recovery initiatives across the State. THE TREASURER THE HONOURABLE CAMERON DICK MP The COVID-19 pandemic has touched everyone and communities $500M $90M in the Darling Downs have not been in electricity and water bill for jobs and skills, including immune to its effects. relief, with a $200 rebate for funding for the Back to Work, households, and a $500 rebate Skilling Queenslanders for Work The Darling Downs Regional for eligible small business and and Reef Assist programs Recovery Action Plan builds on our sole traders immediate commitment to keeping the region moving through extra support for businesses, workers and households – from payroll tax waivers to electricity bill relief. Our recovery approach recognises that local industries such as agribusiness and tourism will continue to play a central role in the region’s economy. It also seeks to harness emerging opportunities $400M $267M land tax relief for property building boost to support home for future growth and to create long-term sustainable local jobs. owners which must be passed owners, ‘tradies’ and construction, We are investing in existing industries and new technologies. This onto tenants in the form of rent including a $5,000 regional home includes an agricultural technology and logistics hub in Toowoomba, relief building grant new feedlot facilities in Allora and a digital connectivity program across the Darling Downs. The Toowoomba Bypass which opened in September 2019, is expected to contribute more than $2.4 billion to the Toowoomba economy. -

Connecting SEQ 2031 an Integrated Regional Transport Plan for South East Queensland

Connecting SEQ 2031 An Integrated Regional Transport Plan for South East Queensland Tomorrow’s Queensland: strong, green, smart, healthy and fair Queensland AUSTRALIA south-east Queensland 1 Foreword Vision for a sustainable transport system As south-east Queensland's population continues to grow, we need a transport system that will foster our economic prosperity, sustainability and quality of life into the future. It is clear that road traffic cannot continue to grow at current rates without significant environmental and economic impacts on our communities. Connecting SEQ 2031 – An Integrated Regional Transport Plan for South East Queensland is the Queensland Government's vision for meeting the transport challenge over the next 20 years. Its purpose is to provide a coherent guide to all levels of government in making transport policy and investment decisions. Land use planning and transport planning go hand in hand, so Connecting SEQ 2031 is designed to work in partnership with the South East Queensland Regional Plan 2009–2031 and the Queensland Government's new Queensland Infrastructure Plan. By planning for and managing growth within the existing urban footprint, we can create higher density communities and move people around more easily – whether by car, bus, train, ferry or by walking and cycling. To achieve this, our travel patterns need to fundamentally change by: • doubling the share of active transport (such as walking and cycling) from 10% to 20% of all trips • doubling the share of public transport from 7% to 14% of all trips • reducing the share of trips taken in private motor vehicles from 83% to 66%. -

Invest Toowoomba

INVEST TOOWOOMBA Your regional gateway to business growth Trade and Investment Queensland presents investors with the opportunity to be a part of a growth story. The confluence of an economy hungry for productivity growth and a region taking the initiative to define its future through infrastructure, agricultural and technology investment makes Toowoomba a uniquely attractive, affordable and quality investment proposition. It’s the base for businesses driving innovation, with room to grow. Contents QUEENSLAND, AUSTRALIA .......................................................................................................................................1 WHY TOOWOOMBA? ..................................................................................................................................................2 TOOWOOMBA FAST FACTS .......................................................................................................................................3 YOUR GUIDE TO TOOWOOMBA INVESTMENT INDUSTRIES ...................................................................................4 TOOWOOMBA HIGHLIGHTS ......................................................................................................................................6 Dynamic industries ................................................................................................................................................6 Strong growth economy .........................................................................................................................................6 -

Toowoomba Bypass

TOOWOOMBA BYPASS TOOWOOMBA, Location Toowoomba, Australia Client Queensland Department of QUEENSLAND, Transport and Main Roads AUSTRALIA Project Value A$1.6 billion Builder Ferrovial and ACCIONA joint Financial adviser venture Project investor Architects Parsons Brinkerhoff and Aurecon joint venture Services Broadspectrum Financial Close August 2015 Completion Date September 2019 Awards Best Road/Highway Project, 2020 Engineering News-Record Global Best Projects Awards Most Innovative National Road Infrastructure Project, 2019 BUILD Infrastructure Awards Silver, Best Transport Project, 2017 PPP Awards Best Road Project, 2016 Partnerships Awards Road Deal of the Year, 2015 PFI Awards Asia Pacific Deal of the Year, 2015 IJGlobal The Toowoomba Bypass is a 41-kilometre bypass which runs to the north of Toowoomba from the Warrego Highway to the Gore Highway via Charlton and was one of Queensland’s highest priority road infrastructure projects. The project will assist in reducing travel time across the Toowoomba range by up to 40 minutes. It will redirect trucks from local roads in Toowoomba’s central business district and enhance freight efficiencies. Plenary is part of the Nexus Infrastructure consortium contracted by the Queensland Government to finance, operate and maintain the project for 25 years. The road partially opened to traffic in December 2018 and was fully completed and operational by September 2019. © Plenary Group 2021 TOOWOOMBA BYPASS Contract terms Design, build, finance and TOOWOOMBA, maintain for 25 years QUEENSLAND, Project -

Toowoomba's House Prices Climb by Sherele Moody 21St January 2017 September Quarter's Activities Were Slow Compared to Previous Sales Periods

Toowoomba's house prices climb by Sherele Moody 21st January 2017 September quarter's activities were slow compared to previous sales periods. "It's a reflection that there are fewer people who are willing and able to buy properties at the moment,” Mr Snow said. "There is a hint of tentativeness from buyers. "I believe there is a sense of caution from buyers generally, they probably don't know why they're being cautious but there is a sense HOUSE buyers are waking because of the low turnover of caution. from their winter and of properties in the three spring slumber as months. "We've had a very positive Toowoomba's market and active October and Highfields had the highest moves towards a November and I would be quarterly media price with "positive and active” expecting the last quarter of that suburb's median sitting summer, the region's 2016 to show good numbers on $525,000. property leader says. of sales. East Toowoomba recorded The city's house prices lifted "We had a very good final a quarterly median of but unit prices dropped in quarter of 2015 and I'm $430,000, Centenary the three months to looking forward to seeing Heights hit $367,000, South September 31. that happen at the end of Toowoomba's median was 2016.” Real Estate Institute of $359,250 and Kearneys Queensland property Spring's median was Mr Snow said the region's statistics reveal the region's $355,000. rental vacancy rate was median house price rose sitting around 3%. Advertisement 1.5% to $350,000 and the A total of 341 Toowoomba median unit price fell 8.1% "We may have seen a slight houses changed hands in to $285,000 in the the September quarter and improvement in vacancy September quarter. -

The Management of the Inland Rail Project by the Australian Track Corporation and the Commonwealth Government

The Management of the Inland Rail project by the Australian Track Corporation and the Commonwealth Government. Comments with reference to: B. Route planning and selection processes C. Connections with other freight infrastructure, including ports and intermodal hubs. b. Route planning and selection processes. Historical. In 2007, the Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads (TMR) initiated a study into the proposed Southern Rail Freight Corridor (SRFC). The study area was from the interstate rail corridor (SGRC) at Kagaru south of Jimboomba, to Rosewood on the western rail line, despite the general area being identified on the 2005 SEQ Regional Plan as being north of Jimboomba. A more suitable corridor to the north was also identified however was discounted by the Queensland Government as it was close to the (then) proposed residential developments at Springfield and Ripley and it was deemed to be inappropriate to bring a high speed freight corridor so close to residential areas. This criterium appears to have been forgotten or discarded with the choice of the proposed alignment utilizing the existing interstate corridor from Kagaru to Acacia Ridge bisecting the residential developments at Flagstone and Greenbank proposed to accommodate 120000 residents in the near future. A draft Assessment Report was released in 2008 and despite many strong and relevant objections, the final report was released in August 2010 and the corridor gazetted by the Queensland Government. This report clearly identifies that ARTC was heavily involved in the selection of the corridor at this phase of the process despite their current claims that they must use the SRFC identified by the Queensland Government. -

Capability Statement

CAPABILITY STATEMENT Core Competencies Integrated transport planning and project evaluation Transport modelling Strategic planning for public transport Toll road analysis Accessibility analysis Statistical and economic analysis Land use projections TransPosition is the GIS and technical software development trading name of Peter Davidson Consulting, Past Performance which has operated since 1993, with a Sydney Motorways Corporation Bid (Traffic modelling), Pacific Part- special focus on the nerships, 2017-2018 analytical side of Queens Wharf Development Bid Review (Traffic), Department of transport, software State Development, Infrastructure and Planning Queensland, 2014- development and 2015 land use planning. Surat Basin Transport Strategy, Queensland Transport and Main With a client list that Roads, 2015 includes a range of Queensland Motorways Bid, Abertis Infraestructuras et al, 2014 local governments, Toowoomba Second Range Crossing Business Case, Projects state agencies, na- Queensland, 2013 tional organisations and private develop- Clem 7 Bid Assessment, UBS, 2013 ers; TransPosition Toowoomba Sub Regional Transport Study, Stage 1 and 2, Queens- has a depth and land Transport and Main Roads (TMR), 2012-2013 breadth of experience Toowoomba Bypass Business Case Review, TMR, 2011 that makes it particu- Review of New England Highway Upgrade, TMR, 2011 larly well suited to TransApex Strategic Advice, Queensland Transport, 2006-2008 integrated, multi- Brisbane Urban Growth Model, Brisbane City Council (BCC), 2007-