Place Name Restoration in Haudenosaunee Territory: Frameworks for Language and Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXONYMS and OTHER GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Drago Perko, Peter Jordan, Blaž Komac MATJAŽ GERŠIČ MATJAŽ Slovenia As an Exonym in Some Languages

57-1-Special issue_acta49-1.qxd 5.5.2017 9:31 Page 99 Acta geographica Slovenica, 57-1, 2017, 99–107 EXONYMS AND OTHER GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Drago Perko, Peter Jordan, Blaž Komac MATJAŽ GERŠIČ MATJAŽ Slovenia as an exonym in some languages. Drago Perko, Peter Jordan, Blaž Komac, Exonyms and other geographical names Exonyms and other geographical names DOI: http: //dx.doi.org/10.3986/AGS.4891 UDC: 91:81’373.21 COBISS: 1.02 ABSTRACT: Geographical names are proper names of geographical features. They are characterized by different meanings, contexts, and history. Local names of geographical features (endonyms) may differ from the foreign names (exonyms) for the same feature. If a specific geographical name has been codi - fied or in any other way established by an authority of the area where this name is located, this name is a standardized geographical name. In order to establish solid common ground, geographical names have been coordinated at a global level by the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) since 1959. It is assisted by twenty-four regional linguistic/geographical divisions. Among these is the East Central and South-East Europe Division, with seventeen member states. Currently, the divi - sion is chaired by Slovenia. Some of the participants in the last session prepared four research articles for this special thematic issue of Acta geographica Slovenica . All of them are also briefly presented in the end of this article. KEY WORDS: geographical name, endonym, exonym, UNGEGN, cultural heritage This article was submitted for publication on November 15 th , 2016. ADDRESSES: Drago Perko, Ph.D. -

Hungary: Jewish Family History Research Guide Hungary (Magyarorszag) Like Most European Countries, Hungary’S Borders Have Changed Considerably Over Time

Courtesy of the Ackman & Ziff Family Genealogy Institute Updated June 2011 Hungary: Jewish Family History Research Guide Hungary (Magyarorszag) Like most European countries, Hungary’s borders have changed considerably over time. In 1690 the Austrian Hapsburgs completed the reconquest of Hungary and Transylvania from the Ottoman Turks. From 1867 to 1918, Hungary achieved autonomy within the “Dual Monarchy,” or Austro-Hungarian Empire, as well as full control over Transylvania. After World War I, the territory of “Greater Hungary” was much reduced, so that areas that were formerly under Hungarian jurisdiction are today located within the borders of Romania, Ukraine, Slovakia, Poland, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, and Yugoslavia (Serbia). Hungary regained control over some of these areas during the Holocaust period, but lost them again in 1945. Regions that belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary before the Treaty of Trianon (1920): Burgenland (Austria), Carpathian Ruthenia (from 1920 to 1938 part of Czechoslovakia, now Ukraine), Medimurje/Murakoz (Croatia), Prekmuje/Muravidek (Slovenia), Transylvania/Erdely-inc. Banat (Romania), Crisana/Partium (Romania), Maramures/Maramaros (Romania), Szeklerland/Szekelyfold (Romania); Upper Hungary/ Felvidek (Slovakia); Vojvodina/Vajdasag (Serbia, Croatia); Croatia (Croatia), Slavonia (Croatia); Separate division- Fiume (Nowadays Rijeka, Croatia) How to Begin Follow the general guidelines in our fact sheets on starting your family history research, immigration records, naturalization records, and finding your ancestral town. Determine whether your town is still within modern-day Hungary and in which county (megye) and district (jaras) it is located. If the town is not in modern Hungary, see our fact sheet for the country where it is currently located. A word of caution: Many towns in Hungary have the same name, and to distinguish among them, a prefix is usually added based upon the county or a nearby city or river. -

Putting Frisian Names on the Map

GEGN.2/2021/68/CRP.68 15 March 2021 English United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names Second session New York, 3 – 7 May 2021 Item 12 of the provisional agenda * Geographical names as culture, heritage and identity, including indigenous, minority and regional languages and multilingual issues Putting Frisian names on the map Submitted by the Netherlands** * GEGN.2/2021/1 ** Prepared by Jasper Hogerwerf, Kadaster GEGN.2/2021/68/CRP.68 Introduction Dutch is the national language of the Netherlands. It has official status throughout the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In addition, there are several other recognized languages. Papiamentu (or Papiamento) and English are formally used in the Caribbean parts of the Kingdom, while Low-Saxon and Limburgish are recognized as non-standardized regional languages, and Yiddish and Sinte Romani as non-territorial minority languages in the European part of the Kingdom. The Dutch Sign Language is formally recognized as well. The largest minority language is (West) Frisian or Frysk, an official language in the province of Friesland (Fryslân). Frisian is a West Germanic language closely related to the Saterland Frisian and North Frisian languages spoken in Germany. The Frisian languages as a group are closer related to English than to Dutch or German. Frisian is spoken as a mother tongue by about 55% of the population in the province of Friesland, which translates to some 350,000 native speakers. In many rural areas a large majority speaks Frisian, while most cities have a Dutch-speaking majority. A standardized Frisian orthography was established in 1879 and reformed in 1945, 1980 and 2015. -

Database of German Exonyms

GEGN.2/2021/46/CRP.46 15 March 2021 English United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names 2021 session New York, 3 – 7 May 2021 Item 13 of the provisional agenda * Exonyms Database of German Exonyms Submitted by Germany** Summary The permanent committee on geographical names (Ständiger Ausschuss für geographische Namen) has published the third issue of its list of German exonyms as a database. The list follows the relevant resolutions adopted by the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names and includes slightly more than 1,500 common German exonyms. It is therefore entirely possible to implement the recommendations of the toponymic experts as laid down in resolutions VIII/4, V/13, III/18, III/9, IV/20, II/28 (available at www.ngii.go.kr/portal/ungn/mainEn.do) which addresses the use of exonyms. The database software is open source. The database can be accessed on the permanent committee’s website as open data under a Creative Commons licence. The data sets can be queried by means of a user interface equipped with an extensive search function, or retrieved in the GeoPackage data format for geographic information system, which is non-proprietary, platform-independent and standards-based. * GEGN.2/2021/1 ** Prepared by Roman Stani-Fertl (Austria), submitted on behalf of the Permanent Committee on Geographical Names (Ständiger Ausschuss für geographische Namen – StAGN) GEGN.2/2021/46/CRP.46 Background In 2002, the Permanent Committee on Geographical Names representing the German speaking countries, has published the second edition of the list of “Selected German Language Exonyms”. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Generative Syntax: a Cross-Linguistic Approach

Generative Syntax: A Cross-Linguistic Approach Michael Barrie Sogang University May 30, 2021 2 Generative Syntax: A Cross-Linguistic Introduction ľ 2021 by Michael Barrie is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ (한국어: https: //creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.ko) by-nc-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This license requires that reusers give credit to the creator. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only. If others modify or adapt the material, they must license the modified material under identical terms. Contents 1 Foundations of the Study of Language 13 1.1 The Science of Language .................................... 13 1.2 Prescriptivism versus Descriptivism .............................. 15 1.3 Evidence of Syntactic Knowledge ............................... 17 1.4 Syntactic Theorizing ....................................... 18 Key Concepts .............................................. 20 Exercises ................................................. 21 Further Reading ............................................ 22 2 The Lexicon and Theta Relations 23 2.1 Restrictions on lexical items: What words want and need ................ 23 2.2 Thematic Relations and θ-Roles ................................ 25 2.3 Lexical Entries ......................................... -

Indigenous Language Revitalization on Social Media During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 239–266 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24976 Revised Version Received: 10 Mar 2021 #KeepOurLanguagesStrong: Indigenous Language Revitalization on Social Media during the Early COVID-19 Pandemic Kari A. B. Chew University of Oklahoma Indigenous communities, organizations, and individuals work tirelessly to #Keep- OurLanguagesStrong. The COVID-19 pandemic was potentially detrimental to Indigenous language revitalization (ILR) as this mostly in-person work shifted online. This article shares findings from an analysis of public social media posts, dated March through July 2020 and primarily from Canada and the US, about ILR and the COVID-19 pandemic. The research team, affiliated with the NEȾOL- ṈEW̱ “one mind, one people” Indigenous language research partnership at the University of Victoria, identified six key themes of social media posts concerning ILR and the pandemic, including: 1. language promotion, 2. using Indigenous languages to talk about COVID-19, 3. trainings to support ILR, 4. language ed- ucation, 5. creating and sharing language resources, and 6. information about ILR and COVID-19. Enacting the principle of reciprocity in Indigenous research, part of the research process was to create a short video to share research findings back to social media. This article presents a selection of slides from the video accompanied by an in-depth analysis of the themes. Written about the pandemic, during the pandemic, this article seeks to offer some insights and understandings of a time during which much is uncertain. Therefore, this article does not have a formal conclusion; rather, it closes with ideas about long-term implications and future research directions that can benefit ILR. -

Country Compendium

Country Compendium A companion to the English Style Guide July 2021 Translation © European Union, 2011, 2021. The reproduction and reuse of this document is authorised, provided the sources and authors are acknowledged and the original meaning or message of the texts are not distorted. The right holders and authors shall not be liable for any consequences stemming from the reuse. CONTENTS Introduction ...............................................................................1 Austria ......................................................................................3 Geography ................................................................................................................... 3 Judicial bodies ............................................................................................................ 4 Legal instruments ........................................................................................................ 5 Government bodies and administrative divisions ....................................................... 6 Law gazettes, official gazettes and official journals ................................................... 6 Belgium .....................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Judicial bodies .......................................................................................................... 10 Legal instruments ..................................................................................................... -

The Cayuga Chief Jacob E. Thomas: Walking a N~Rrow Path Between Two Worlds

THE CAYUGA CHIEF JACOB E. THOMAS: WALKING A N~RROW PATH BETWEEN TWO WORLDS Takeshi Kimura Faculty of Humanities Yamaguchi University 1677-1 Yoshida Yamaguchi-shi 753-8512 Japan Abstract I Resume The Cayuga Chief Jacob E. Thomas (1922-1998) of the Six Nations Reserve, Ontario, worked on teaching and preserving the oral Native languages and traditions ofthe Longhouse by employing modern technolo gies such as audio- and video recorders and computers. His primary concern was to transmit and document them as much as possible in the face of their possible loss. Especially, he emphasized teaching the lan guage and religious knowledge together. In this article, researched and written before his death, I discuss the way he taught his classes, examine the educational materials he produced, and assess their features. I also examine several reactions toward his efforts among Native people. De son vivant Jacob E. Thomas (1922-1998), chef des Cayugas de la Reserve des Six Nations, en Ontario, a travaille a I'enseignement et a la preservation des langues parlees autochtones et des traditions du Long house. Pour ce faire, il a eu recours aux techniques d'enregistrement audio et video ainsi qu'a I'informatique. Devant Ie declin possible des langues et des traditions autochtones, son but principal a ete de les enregistrer et de les classifier pour les rendre accessible a tous. II a particulierement mis I'accent sur la necessite d'enseigner conjointement la langue et la religion. Dans cet article, dont la recherche et la redaction ont ete accomplies avant la mort de Thomas, j'examine son enseignement en ciasse de meme que Ie materiel pedagogique qu'il a cree et en evalue les caracteristiques. -

Dictionary of Slovenian Exonyms Explanatory Notes

GEOGRAFSKI INŠTITUT ANTONA MELIKA ZNANSTVENORAZISKOVALNI CENTER SLOVENSKE AKADEMIJE ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI ANTON MELIK GEOGRAPHICAL INSTITUTE OF ZRC SAZU DICTIONARY OF SLOVENIAN EXONYMS EXPLANATORY NOTES Drago Kladnik Drago Perko AMGI ZRC SAZU Ljubljana 2013 1 Preface The geocoded collection of Slovenia exonyms Zbirka slovenskih eksonimov and the dictionary of Slovenina exonyms Slovar slovenskih eksonimov have been set up as part of the research project Slovenski eksonimi: metodologija, standardizacija, GIS (Slovenian Exonyms: Methodology, Standardization, GIS). They include more than 5,000 of the most frequently used exonyms that were collected from more than 50,000 documented various forms of these types of geographical names. The dictionary contains thirty-four categories and has been designed as a contribution to further standardization of Slovenian exonyms, which can be added to on an ongoing basis and used to find information on Slovenian exonym usage. Currently, their use is not standardized, even though analysis of the collected material showed that the differences are gradually becoming smaller. The standardization of public, professional, and scholarly use will allow completely unambiguous identification of individual features and items named. By determining the etymology of the exonyms included, we have prepared the material for their final standardization, and by systematically documenting them we have ensured that this important aspect of the Slovenian language will not sink into oblivion. The results of this research will not only help preserve linguistic heritage as an important aspect of Slovenian cultural heritage, but also help preserve national identity. Slovenian exonyms also enrich the international treasury of such names and are undoubtedly important part of the world’s linguistic heritage. -

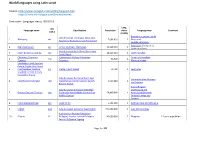

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

3115 Eblj Article 2 (Was 3), 2008:Eblj Article

Early Northern Iroquoian Language Books in the British Library Adrian S. Edwards An earlier eBLJ article1 surveyed the British Library’s holdings of early books in indigenous North American languages through the example of Eastern Algonquian materials. This article considers antiquarian materials in or about Northern Iroquoian, a different group of languages from the eastern side of the United States and Canada. The aim as before is to survey what can be found in the Library, and to place these items in a linguistic and historical context. In scope are printed media produced before the twentieth century, in effect from 1545 to 1900. ‘I’ reference numbers in square brackets, e.g. [I1], relate to entries in the Chronological Checklist given as an appendix. The Iroquoian languages are significant for Europeans because they were the first indigenous languages to be recorded in any detail by travellers to North America. The family has traditionally been divided into a northern and southern branch by linguists. So far only Cherokee has been confidently allocated to the southern branch, although it is possible that further languages became extinct before their existence was recorded by European visitors. Cherokee has always had a healthy literature and merits an article of its own. This survey therefore will look only at the northern branch. When historical records began in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Northern Iroquoian languages were spoken in a large territory centred on what is now the north half of the State of New York, extending across the St Lawrence River into Quebec and Ontario, and southwards into Pennsylvania.