Determinants of Human Security and Hard Security in Ajloun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

FROM DIWAN TO PALACE: JORDANIAN TRIBAL POLITICS AND ELECTIONS by LAURA C. WEIR Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Pete Moore Department of Political Science CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January, 2013 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Laura Weir candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Pete Moore, Ph.D (chair of the committee) Vincent E. McHale, Ph.D. Kelly McMann, Ph.D. Neda Zawahri, Ph.D. (date) October 19, 2012 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables v List of Maps and Illustrations viii List of Abbreviations x CHAPTERS 1. RESEARCH PUZZLE AND QUESTIONS Introduction 1 Literature Review 6 Tribal Politics and Elections 11 Case Study 21 Potential Challenges of the Study 30 Conclusion 35 2. THE HISTORY OF THE JORDANIAN ―STATE IN SOCIETY‖ Introduction 38 The First Wave: Early Development, pre-1921 40 The Second Wave: The Arab Revolt and the British, 1921-1946 46 The Third Wave: Ideological and Regional Threats, 1946-1967 56 The Fourth Wave: The 1967 War and Black September, 1967-1970 61 Conclusion 66 3. SCARCE RESOURCES: THE STATE, TRIBAL POLITICS, AND OPPOSITION GROUPS Introduction 68 How Tribal Politics Work 71 State Institutions 81 iii Good Governance Challenges 92 Guests in Our Country: The Palestinian Jordanians 101 4. THREATS AND OPPORTUNITIES: FAILURE OF POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE RISE OF TRIBAL POLITICS Introduction 118 Political Threats and Opportunities, 1921-1970 125 The Political Significance of Black September 139 Tribes and Parties, 1989-2007 141 The Muslim Brotherhood 146 Conclusion 152 5. -

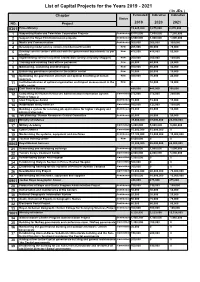

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

Jordan Middle East DISCUSSION PAPER and North Africa Transition Fund September 2017 Middle East and North Africa Transition Fund

Towards a new partnership between government and youth in Jordan Middle East DISCUSSION PAPER and North Africa Transition Fund September 2017 Middle East and North Africa Transition Fund ABOUT THE OECD MENA TRANSITION FUND OF THE DEAUVILLE PARTNERSHIP The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an international body that promotes In May 2011, the Deauville Partnership was launched as a policies to improve the economic and social well-being long-term global initiative that provides Arab countries in of people around the world. It is made up of 35 member transition with a framework based on technical support countries, a secretariat in Paris, and a committee, drawn to strengthen governance for transparent, accountable from experts from government and other fields, for each governments and to provide an economic framework for work area covered by the organisation. The OECD provides sustainable and inclusive growth. a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems. We The Deauville Partnership has committed to support collaborate with governments to understand what drives Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen and the economic, social and environmental change. We measure Transition Fund is one of the levers to implement this productivity and global flows of trade and investment. commitment. The Transition Fund demonstrates a joint commitment by G7 members, Gulf and regional partners, For more information, please visit www.oecd.org. and international and regional financial institutions to support the efforts of the people and governments of the Partnership countries as they overhaul their economic systems to promote more accountable governance, broad- based, sustainable growth, and greater employment opportunities for youth and women. -

The Holy Land but Did Not Enter It and Where a Church and a Monastery Were Built to Honor Him

Content Jordan’s Religious Legacy 1 Baptism Site/Bethany Beyond the Jordan 3 Hill of Elijah 4 Pisgah / Mount Nebo 5 Medeba / Madaba 6 Machaerus / Mukawir 7 Anjara 7 Prophet Elijah’s Shrine 8 Mephaath / Umm Ar-Rasas 9 Gadara / Umm Qays 10 Gerasa / Jerash 11 Rabbath-Ammon/ Amman 12 Petra 13 Arnon Valley / Wadi Mujib 14 Pella / Tabaqat Fahl 15 Umm Al-Jimal 16 Lot’s Cave 17 Heshbon/ Hisban 18 Rehab 19 Dibon / Dhiban 19 The Early Church in Aqaba 20 Map of Biblical Jordan 21 Jordan’s Religious Legacy The land of modern day Jordan has been the site of signifcant events in the history of Christianity spanning across centuries throughout the New and Old Testaments. It is because of this religious signifcance that sites all around Jordan have been designated as pilgrimage sites and have been visited by Pope John Paul VI, Pope John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis within the past half century. As a land dedicated to religious coexistence, the country of Jordan maintains these religious sites for the use of pilgrims from all around the world. 1 Jordan’s Religious Legacy Today I am in Jordan, a land familiar to me from the Holy Scriptures – a land sanctifed by the presence of Jesus Himself, by the presence of Moses, Elijah and John the Baptist; and of saints and martyrs of the early Church. Yours is a land noted for its hospitality and openness to all. Pope John Paul II during his Jubilee Pilgrimage in 2000 Pope John Paul VI Pope John Paul II at Mount Nebo Pope Benedict XVI at the Baptism site Pope Francis 2 Baptism Site/ Bethany Beyond the Jordan The Bible narrates that people used to travel from Jerusalem and Yahuda and from the countries bordering Jordan to be baptized by John the Baptist. -

Jordan: a Need Assessment

TECHNICAL REPORT Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Jordan: a need assessment Amman, South Shuneh, Al-Azraq, Ajloun (Jordan), 14-19 May 2017 Objectives The overall objective of the mission was to carry out a situation analysis on cutaneous leishmaniasis in the country, following a request by MoH Jordan through WHO Jordan, as originally proposed and planned in the Joint Collaboration Programme 2016-2017 between WHO and MoH. Its aims included to review the epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Jordan and the control measures currently implemented in the country, and to provide MoH Jordan with advice in regard to the above. The mission was led by an expert in leishmaniasis, Prof. Riadh Ben-Ismail, from "Institut Pasteur" in Tunis, as WHO Temporary Adviser, accompanied by Dr Albis Francesco Gabrielli, Regional Adviser, NTD, WHO/EMRO, and by Dr Lora AlSawalha and Dr Akram Wajih, WHO/Jordan. The mission consisted of meetings in Amman, travel to endemic areas and meetings with local health authorities, and was concluded by a national workshop attended by all actors working in leishmaniasis in Jordan. As an outcome of the workshop, recommendations were formulated. 1. BACKGROUND Cutaneous leishmaniasis is endemic in some geographical areas of Jordan, where its epidemiology and distribution are generally well known. The disease is known in Jordanian dialect as "gwedha" - a reference to the traditional treatment of the lesions, based on heating or burning). The most common form is zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L. major, present in several rural foci especially along the River Jordan valley (lowlands) and the desert areas in southern Jordan (vector: Ph. -

History and Culture.Indd

History & Culture Table of Contents Map of Jordan 1 L.Tiberius Umm Qays Welcome 2 Irbid Jaber Amman 4 Pella Hemmeh Ramtha er As-Salt HISTORY & CULTURE12 ITINERARIES Ajlun Mafraq Madaba 14 dan Riv Jerash Deir 'Alla Umm al-Jimal 1 Day Tour Options: Jor Umm Ar-Rasas1. Jerash, Ajlun 16 ey Salt Qasr Al Hallabat Mount Nebo2. Amman (City Tour) 17 all Zarqa Marka 3. Madaba, Mount Nebo, Bethany Beyond the Jordan V dan Jordan Valley & The Dead Sea 18 Jor Amman Iraq al-Amir Qusayr Amra Azraq Karak 20 Bethany Beyond The Jordan Mt. Nebo Qasr Al Mushatta 3 Day Itinerary: Dead Sea Spas Queen Alia Qasr Al Kharrana Petra 22 Madaba International Day 1. Amman, Jerash, Madaba and Dead Sea - Overnight in Ammana Airport e Hammamat Ma’in Aqaba Day 2. Petra - Overnight in26 Little Petra S d Dhiban a Umm Ar-Rasas Jerash Day 3. Karak, Madaba and30 Mount Nebo - Overnight in Ammane D Ajlun 36 5 Day Itinerary: Umm Al-Jimal 38 Qatraneh Day 1. Amman, Jerash, Ajlun - Overnight in Amman Karak Pella 39 Mu'ta Day 2. Madaba, Mount Nebo, Karak - Overnight at PetraAl Mazar aj-Janubi Umm QaysDay 3. Petra - Overnight at40 Petra Shawbak Day 4. Wadi Rum - Overnight42 Dead Sea Tafileh Day 5. Bethany Beyond The Jordan MAP LEGEND Desert Umayyad Castles 44 History & Culture Itineraries 49 Historical Site Shawbak Highway Castle Desert Wadi Musa Petra Religious Site Ma'an Airport Ras an-Naqab Road For further information please contact: Highway Jordan Tourism Board: Tel: +962 6 5678444. It is open daily (08:00- Railway 16:00) except Fridays. -

Women's Political Participation in Jordan

MENA - OECD Governance Programme WOMEN’S Political Participation in JORDAN © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 2 WOMEN’S POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN JORDAN: BARRIERS, OPPORTUNITIES AND GENDER SENSITIVITY OF SELECT POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS MENA - OECD Governance Programme © OECD 2018 | Women’s Political Participation in Jordan | Page 3 OECD The mission of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is to promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world. It is an international organization made up of 37 member countries, headquartered in Paris. The OECD provides a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems within regular policy dialogue and through 250+ specialized committees, working groups and expert forums. The OECD collaborates with governments to understand what drives economic, social and environmental change and sets international standards on a wide range of things, from corruption to environment to gender equality. Drawing on facts and real-life experience, the OECD recommend policies designed to improve the quality of people’s. MENA - OECD MENA-OCED Governance Programme The MENA-OECD Governance Programme is a strategic partnership between MENA and OECD countries to share knowledge and expertise, with a view of disseminating standards and principles of good governance that support the ongoing process of reform in the MENA region. The Programme strengthens collaboration with the most relevant multilateral initiatives currently underway in the region. In particular, the Programme supports the implementation of the G7 Deauville Partnership and assists governments in meeting the eligibility criteria to become a member of the Open Government Partnership. -

THE STARTUP GUIDE Business in Jordan

Your complete guide to registering and licensing a small THE STARTUP GUIDE business in Jordan Find out what to do, where to go and what fees are required to formalize your small business in this simple, step-by-step guide Contents WHY SHOULD I REGISTER AND LICENSE MY BUSINESS? ........................................................................................ 2 WHAT ARE THE STEPS I NEED TO TAKE IN ORDER TO FORMALIZE MY BUSINESS? ............................................... 3 HOW DO I KNOW WHAT TYPE OF BUSINESS TO REGISTER? ................................................................................. 4 HOW DO I CHOOSE A BUSINESS STRUCTURE THAT’S RIGHT FOR ME? ................................................................. 6 I’VE CHOSEN MY BUSINESS STRUCTURE… WHAT NEXT? ...................................................................................... 8 I’VE GOTTEN MY PRE-APPROVALS. HOW DO I REGISTER MY BUSINESS? ............................................................. 9 A) REGISTERING AN INDIVIDUAL ESTABLISHMENT ........................................................................................ 10 B) REGISTERING A GENERAL PARTNERSHIP OR LIMITED PARTNERSHIP COMPANY ...................................... 13 C) REGISTERING A LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY ........................................................................................... 16 D) REGISTERING A PRIVATE SHAREHOLDING COMPANY................................................................................ 20 I’VE REGISTERED MY BUSINESS. HOW CAN I SET -

Intention to Use Contraceptives in Jordan

Intention to Use Contraceptives in Jordan: Further Analysis of the Jordan Population and Family Health Survey 2017-18 DHS Further Analysis Reports No. 141 December 2020 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Sara Riese. Further Analysis Reports No. 141 Intention to Use Contraceptives in Jordan: Further Analysis of the Jordan Population and Family Health Survey 2017-18 Sara Riese1,2 ICF Rockville, Maryland, USA December 2020 1 ICF 2 The DHS Program Corresponding author: Sara Riese, International Health and Development, ICF, 530 Gaither Road, Suite 500, Rockville, MD 20850, USA; phone: +1 301-572-0546; fax: +1 301-407-6501; email: [email protected] Acknowledgments: This study was supported by the USAID/Jordan. The USAID Mission in Jordan provided support and funding under the DHS-8 contract. Many thanks to my colleague, Christina Juan, for brainstorming and discussions during the Jordan Further Analysis report development process. Gratitude is extended to Shireen Assaf and Yodit Bekele for their thoughtful review and comments, as well as to our external reviewers, Hana Banat, John Callanta, and Samah Al-Quran. Editor: Diane Stoy Document Production: Natalie Shattuck This report presents findings from a further analysis of the 2017-18 Jordan Population and Family Health Survey (JPFHS). This report is a publication of The DHS Program which collects, analyzes, and disseminates data on fertility, family planning, maternal and child health, nutrition, and HIV/AIDS. Funding was provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) through the DHS Program (#720-0AA-18C-00083). -

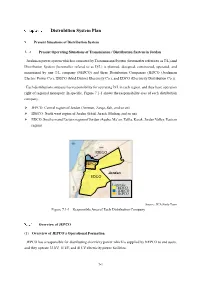

Distrubition System Plan

Distrubition System Plan Present Situations of Distribution System Present Operating Situations of Transmission / Distribution System in Jordan Jordanian power system which is consisted by Transmission System (hereinafter refered to as T/L) and Distribution System (hereinafter refered to as D/L) is planned, designed, constructed, operated, and maintained by one T/L company (NEPCO) and three Distribution Companies (JEPCO (Jordanian Electric Power Co.), IDECO (Irbid District Electricity Co.), and EDCO (Electricity Distribution Co.)). Each distribution company has responsibility for operating D/L in each region, and they have operation right of regional monopoly. In specific, Figure 7.1-1 shows the responsibility area of each distribution company. JEPCO: Central region of Jordan (Amman, Zarqa, Salt, and so on) IDECO: North west region of Jordan (Irbid, Jarash, Mufraq, and so on) EDCO: Southern and Eastern region of Jordan (Aqaba, Ma’an, Tafila, Karak, Jordan Valley, Eastern region) IDECO JEPCO Jordan EDCO Legends: ■:EDCO ■:IDECO ■:JEPCO Source: JICA Study Team Figure 7.1-1 Responsible Area of Each Distribution Company Overview of JEPCO (1) Overview of JEPCO’s Operational Formation JEPCO has a responsible for distributing electricity power which is supplied by NEPCO to end users, and they operate 33 kV, 11 kV, and 415 V electricity power facilities. 7-1 Headquarters of JEPCO is located in Amman, and they operate the distribution facilities from secondary side bus of each BSP to terminals of end user. Organization chart of JEPCO is shown in Figure 7.1-2. JEPCO buys the electricity power from NEPCO, and the boundary point of trading is secondary side of BSP. -

Role of King Abdullah II Fitness Award in Improving the Physical Level of the Tenth Grade from the Point of View of Teachers in the Northern Governorates

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.7, No.20, 2016 Role of King Abdullah II Fitness Award in Improving the Physical Level of the Tenth Grade from the Point of View of Teachers in the Northern Governorates Dr.Hamed Mohammed Doum Associate professor -Department of Educational Sciences, Ajloun University College, AL-Balqa Applied University. JORDAN Abstract The study aimed to identify the role of King Abdullah II fitness award in improving the physical level to the tenth grade from the point of view of teachers in the of Northern region governates. The researcher used the descriptive survey method for its suitability to the objectives of the study, the researcher built a questionnaire that consisted of (20) items and confirmed its validity and reliability, a sample of 183 teachers were chosen from the northern governorates (Irbid, Ajloun, Jerash). The results showed a high degree to the role of King Abdullah fitness award in improving the physical level of the tenth grade in the north northern governorates. And that there were no statistically significant differences at the level of (0.05) for the role of King Abdullah fitness award in improving the physical level to the tenth grade in the Northern Governorates according to the variables of (gender, scientific expertise, qualification). The study suggested some recommendations like giving importance to the award implementation, encouraging the students towards fitness exercise to improve their physical level, raising awareness among all students and teachers of the importance of the award. Keywords : King Abdullah award, fitness, physical level. -

Jordan: Ajloun Governorate Reference Map

Jordan: Ajloun Governorate Reference Map Taibeh Taibeh Dair Ess'eneh Rkhayyem Bait Yafa Irbid Irbid Jinien Essafa Iskayeen Sammo' Shaikh Hussein Alyah Aidoon Ham Natfeh Abu Ziyad Kofor Kiefia Sarieh Zmal Zamaliyyeh Dair Abi Sa'id Johfiyyeh Diar Yoosef Hoafa El-Mazar Jeffien Sowwan Kofor El-Ma' Enbeh Hoson Abu El-Qain Tebneh Habka Mazar Shamali Raqqah Kora Kora Ashrafiyyeh Mazar Ash-shamali Mazar Ash-shamali Bani ObaidBani Obaid Kofor Rakeb Samad Rahmah Tabaqat Fahl Mashari'e Ibrahimiyyeh (Sarras) Za'tara Bait Iedes Ketem Zoobya dir al birak Kherbet El-Hawi Rhaba Shatana Kofor Owan Ghwar Ashamalya Ghwar Ashamalya NULL Marzeh Kofor Abiel Jdaitta NULL NULL Rahwah Bier Eddalyeh NULL NULL Arjan Samta Halawah Ras Munif NULL Sakhera NULL NULL Sakhrah Tayyarah Mehnah Hashemiyyeh NULL Kofor Khall NULL Ebbien Karkamah Shtafaina Sbiereh Ajloun Ebellien NULL Dair Smadiyyeh Shamali NULL souan Qarn Dair Smadiyyeh Janoobi Ain Janna Sakhneh NULL Ajloun Ajloun Slaikhat Ajloun Wahadneh JORDAN Meqebleh Soof Anjarah Mukhayyam Soof Kofranjah Jerash Shkarah NULL Jarash NULL Riemoon Sakeb Berkeh NULL Zaqreet Wahadneh Oqdeh NULL Nahleh Krayymeh Um Erramel Harth balass MukhayyMaman Gshiayzyzeet hHashem Nubah Sofsafah Haddadeh Khellet Wardeh Um El-Yanabi'e Jamla Safieneh Kellet Salem Sakhneh NULL Fakhreh Zarra'ah kaeb al maloul Jerash Kofranja Kofranja Rashaydeh balass Shkarah Najdeh Amameh Rasoon Balawneh thaghret zbad Oasarah Gabal Aghdar Keshiebeh El-Foqa' Merjam Berma Erjan Hooneh Khazma Mansoorah (khshaibeh) Fawara Sena'ar Dherar Mashtal Faisal Shaikh Mefrej