Tanganyika: One Year Later December 9, 1962 Mr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 104 Jan - April 2013

Tanzanian Affairs Text 1 Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 104 Jan - April 2013 Big Progress in Transport Death of a Journalist A Tale of Two Museums Meaning in Miscellanea Faith News BIG PROGRESS IN TRANSPORT New ‘no frills’ airline launched A new ‘no frills’ airline called ‘Fastjet’, modelled on the Easyjet airline which has revolutionised air travel in Europe, was launched in Africa on November 29th. The famous entrepreneur Sir Stelios Haji Ioannou, who started Easyjet, has joined with Lonrho’s airline, which flies in West Africa to establish the new group. Significantly, Fastjet chose to begin in Tanzania and Dar es Salaam airport will be its first African hub. It has already leased two planes, has 15 more on order (all Airbus A319s with a capacity for up to 156 passengers), and plans to build up to a fleet of 40. Tanzania’s dynamic Minister of Transport, Dr Harrison Mwakyembe, spoke about the unusually speedy implementation of this vast project when he addressed a crowded AGM of the Britain Tanzania Society in London in mid November. Fastjet plans to expand from Tanzania into Kenya in 2013 and then to Ghana and Angola which are already served by the Lonrho airline. It is advertising for pilots, passenger services agents, cabin crew and crew managers and also for retail sales agents in the East African media. ‘Taking the country by storm.’ The Citizen wrote that the launch had taken the country by storm, as the airline transported 900 passengers in eight flights from Dar to Mwanza and Kilimanjaro and back on its first day! The airline’s management told investors that demand for seats on these routes far outstripped supply. -

The Case of Tanzania

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced frommicrofilm the master. U M I films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/ 761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Order Number 9507836 War as a social trap: The case of Tanzania Francis, Joyce L., Ph.D. -

AC Vol 45 No 9

www.africa-confidential.com 30 April 2004 Vol 45 No 9 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL TANZANIA 3 SUDAN Troubled isles The union between the mainland Mass murder and Zanzibar – 40 years old this Ten years after Rwanda’s genocide, the NIF regime kills and displaces week – remains a political hotspot, tens of thousands of civilians in Darfur – with impunity mainly because the ruling CCM has rigged two successive elections on Civilians in Darfur continue to die as a result of the National Islamic Front regime’s ethnic cleansing and the islands. Some hope that former in the absence of serious diplomatic pressure. United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan has warned OAU Secretary General Salim that international military intervention might be required to stop the slaughter in Darfur, while senior UN Ahmed Salim of Zanzibar will take officials refer to the NIF regime’s scorched earth policy as ‘genocide’ or ‘ethnic cleansing’. Yet last week over from President Mkapa next the UN Commission on Human Rights (UNOHCHR) in Geneva again refused to recommend strong year and negotiate a new settlement with the opposition CUF. action against Khartoum and suppressed its own highly critical investigation, which found that government agents had killed, raped and tortured civilians. On 23 April, the NIF exploited anti-Americanism to defeat a call from the United States and European MALAWI 4Union to reinstate a Special Rapporteur (SR) on Human Rights. At 2003’s annual session, Khartoum had successfully lobbied for the removal as SR of the German lawyer and former Interior Minister Gerhard Bingu the favourite Baum, an obvious candidate for enquiries in Darfur. -

Nakala Ya Mtandao (Online Document) 1 BUNGE LA TANZANIA

Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) BUNGE LA TANZANIA ___________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE _____________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA TANO Kikao cha Thelathini na Tatu - Tarehe 16 Juni, 2014 (Mkutano Ulianza Saa 3.00 Asubuhi) D U A Naibu Spika (Mhe. Job Y. Ndugai) Alisoma Dua SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge tukae. Katibu! HATI ZILIZOWASILISHWA MEZANI: Hati Zifuatazo Ziliwasilishwa Mezani na :- MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA BAJETI: Taarifa ya Kamati ya Bajeti Juu ya Hali ya Uchumi wa Taifa kwa Mwaka 2013 na Mpango wa Maendeleo wa Taifa kwa Mwaka 2014/2015 Pamoja na Tathmini ya Utekelezaji wa Bajeti ya Serikali kwa Mwaka 2013/2014 na Mapendekezo ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Serikali kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2014/2015. MHE. RAJAB MBAROUK MOHAMMED (K.n.y. MSEMAJI MKUU WA KAMBI YA UPINZANI WA OFISI YA RAIS, MAHUSIANO NA URATIBU): Taarifa ya Msemaji Mkuu wa Kambi ya Upinzani wa Ofisi ya Rais (Mahusiano na Uratibu) Juu ya Hali ya Uchumi wa Taifa kwa Mwaka 2013 na Mpango wa Maendeleo wa Taifa kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2014/2015. MHE. CHRISTINA LISSU MUGHWAI (K.n.y. MSEMAJI MKUU WA KAMBI YA UPINZANI WA WIZARA YA FEDHA): Taarifa ya Msemaji Mkuu wa Kambi ya Upinzani wa Wizara ya Fedha juu ya Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Serikali kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2014/2015. Na. 240 Ukosefu wa Hati Miliki MHE. NYAMBARI C. M. NYANGWINE aliuliza:- Ukosefu wa Hatimiliki za Kimila Vijijini unasababisha migogoro mingi ya ardhi baina ya Kaya, Kijiji na Koo na kupelekea kutoweka kwa amani kwa wananchi kama inavyotokea huko Tarime. 1 Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) (a) Je, ni kwa nini Serikali haitoi -

Cwr on EAST AFRICA If She Can Look up to You Shell Never Look Down on Herself

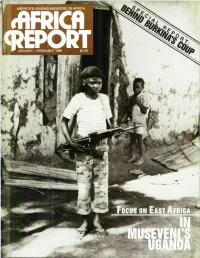

cwr ON EAST AFRICA If she can look up to you shell never look down on herself. <& 1965, The Coca-Cola Company JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1988 AMERICA'S VOLUME 33, NUMBER 1 LEADING MAGAZINE cBFRICfl ON AFRICA A Publication of the (REPORT African-American Institute Letters to the Editor Update The Editor: Andre Astrow African-American Institute Chairman Uganda Randolph Nugent Ending the Rule of the Gun 14 President By Catharine Watson Donald B. Easum Interview with President Yoweri Museveni IK By Margaret A. Novicki and Marline Dennis Kenya Publisher The Dynamics of Discontent 22 Frank E. Ferrari By Lindsey Hilsum Editor-in-Chief Dealing with Dissent Margaret A. Novicki Tanzania Interview with President Ali Hassan Mwinyi Managing Editor 27 Alana Lee By Margaret A. Novicki Acting Managing Editor Politics After Dodoma 30 Daphne Topouzis By Philip Smith Assistant Editor Burkina Special Report Andre Astrow A Revolution Derailed 33 Editorial Assistant By Ernest Harsch W. LaBier Jones Ethiopia On Famine's Brink 40 Art Director By Patrick Moser Joseph Pomar Advertising Director Eritrea: The Food Weapon 44 Barbara Spence Manonelie, Inc. By Michael Yellin (718) 773-9869. 756-9244 Sudan Contributing Editor Prospects for Peace? 45 Michael Maren By Robert M. Press Interns Somalia Joy Assefa Judith Surkis What Price Political Prisoners? 48 By Richard Greenfield Comoros Africa Reporl (ISSN 0001-9836), a non- 52 partisan magazine of African affairs, is The Politics of Isolation published bimonthly and is scheduled By Michael Griffin to appear at the beginning of each date period ai 833 United Nations Plaza. Education New York, N.Y. -

Politics, Decolonisation, and the Cold War in Dar Es Salaam C

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/87426 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Politics, decolonisation, and the Cold War in Dar es Salaam c. 1965-72 by George Roberts A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick, Department of History, September 2016 Politics, decolonisation, and the Cold War in Dar es Salaam, c. 1965-72 Acknowledgements 4 Summary 5 Abbreviations and acronyms 6 Maps 8 Introduction 10 Rethinking the Cold War and decolonisation 12 The ‘Cold War city’ 16 Tanzanian history and the shadow of Julius Nyerere 20 A note on the sources 24 1 – From uhuru to Arusha: Tanzania and the world, 1961-67 34 Nyerere’s foreign policy 34 The Zanzibar Revolution 36 The Dar es Salaam mutiny 38 The creation of Tanzania 40 The foreign policy crises of 1964-65 43 The turn to Beijing 47 Revisiting the Arusha Declaration 50 The June 1967 government reshuffle 54 Oscar Kambona’s flight into exile 56 Conclusion 58 2 – Karibu Dar es Salaam: the political geography of a Cold War city 60 Dar es Salaam 61 Spaces 62 News 67 Propaganda -

Single-Party Rule in a Multiparty Age: Tanzania in Comparative Perspective

SINGLE-PARTY RULE IN A MULTIPARTY AGE: TANZANIA IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement of the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Richard L. Whitehead August, 2009 © by Richard L. Whitehead 2009 All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Title: Single-Party Rule in a Multiparty Age: Tanzania in Comparative Perspective Candidate's Name: Richard L. Whitehead Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2009 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Richard Deeg As international pressure for multiparty reforms swept Africa during the early 1990s, long- time incumbent, such as UNIP in Zambia, KANU in Kenya, and the MCP in Malawi, were simultaneously challenged by widespread domestic demands for multiparty reforms. Only ten years later, after succumbing to reform demands, many long-time incumbents were out of office after holding competitive multiparty elections. My research seeks an explanation for why this pattern did not emerge in Tanzanian, where the domestic push for multiparty change was weak, and, despite the occurrence of three multiparty elections, the CCM continues to win with sizable election margins. As identified in research on semi-authoritarian rule, the post-reform pattern for incumbency maintenance in countries like Togo, Gabon, and Cameroon included strong doses of repression, manipulation and patronage as tactics for surviving in office under to multiparty elections. Comparatively speaking however, governance by the CCM did not fit the typical post-Cold-War semi-authoritarian pattern of governance either. In Tanzania, coercion and manipulation appears less rampant, while patronage, as a constant across nearly every African regime, cannot explain the overwhelming mass support the CCM continues to enjoy today. -

June 17, 1964 Record of Conversation Between Premier Zhou and Second Vice President Rashidi Kawawa

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified June 17, 1964 Record of Conversation between Premier Zhou and Second Vice President Rashidi Kawawa Citation: “Record of Conversation between Premier Zhou and Second Vice President Rashidi Kawawa,” June 17, 1964, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, PRC FMA 108-01318-07. Translated by David Cowhig. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/188126 Summary: Zhou Enlai and Kawawa discuss the diplomatic competition between Taiwan and the PRC, political conditions in Tanzania and Zanzibar, and plans for the Second Asian-African Conference. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Henry Luce Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Confidential Document 500 Ministry of Foreign Affairs document Record of Conversation: Premier Zhou and Second Vice President Rashidi Kawawa (On the morning of June 17, 1964, on the way from the hotel to the airport) (not reviewed by the Prime Minister) -- Concerning the "Two Chinas", the Tanzanian Union, the Second Asian-African Conference, and the Premier’s visit to East Africa - On the morning of June 17th, on the way to the airport by the hotel, the Premier and Kawawa talked about the following issues: (1) On the "Two Chinas" issue. The Premier said that Ambassador He Ying recently visited Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. He had good talks in Northern Rhodesia. Kaunda said that he would establish diplomatic relations with China after independence in October, and he hoped that the Premier would visit North Africa at the time of his visit to East Africa. The situation in Nyasaland is not very good. -

The Collapse of a Pastoral Economy

his research unravels the economic collapse of the Datoga pastoralists of central and 15 Göttingen Series in Tnorthern Tanzania from the 1830s to the beginning of the 21st century. The research builds Social and Cultural Anthropology from the broader literature on continental African pastoralism during the past two centuries. Overall, the literature suggests that African pastoralism is collapsing due to changing political and environmental factors. My dissertation aims to provide a case study adding to the general Samwel Shanga Mhajida trends of African pastoralism, while emphasizing the topic of competition as not only physical, but as something that is ethnically negotiated through historical and collective memories. There are two main questions that have guided this project: 1) How is ethnic space defined by The Collapse of a Pastoral Economy the Datoga and their neighbours across different historical times? And 2) what are the origins of the conflicts and violence and how have they been narrated by the state throughout history? The Datoga of Central and Northern Tanzania Examining archival sources and oral interviews it is clear that the Datoga have struggled from the 1830s to the 2000s through a competitive history of claims on territory against other neighbouring communities. The competitive encounters began with the Maasai entering the Serengeti in the 19th century, and intensified with the introduction of colonialism in Mbulu and Singida in the late 19th and 20th centuries. The fight for control of land and resources resulted in violent clashes with other groups. Often the Datoga were painted as murderers and impediments to development. Policies like the amalgamation measures of the British colonial administration in Mbulu or Ujamaa in post-colonial Tanzania aimed at confronting the “Datoga problem,” but were inadequate in neither addressing the Datoga issues of identity, nor providing a solution to their quest for land ownership and control. -

Credit, Debt, and Urban Living in Kariakoo, Dar Es Salaam

MORALITIES OF OWING AND LENDING: CREDIT, DEBT, AND URBAN LIVING IN KARIAKOO, DAR ES SALAAM By Benjamin Amani Brühwiler A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History-Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT MORALITIES OF OWING AND LENDING: CREDIT, DEBT, AND URBAN LIVING IN KARIAKOO, DAR ES SALAAM By Benjamin Amani Brühwiler The literature on Africans and credit and debt is marked by a double binary. Scholars have tended to separate “traditional” or “informal” credit and debt relations from “modern” or “formal” financial institutions and instruments. In addition, scholars have either focused on the role credit and debt relations played in the economic realm or they have examined the social and cultural significance of debt and credit. As a result, the prevailing picture of Africans and finance in twentieth-century urban Africa is one of inadequacy, lack, and exclusion: the inadequacy of traditional forms of credit in market economies, Africans’ lack of access to formal financial institutions, and their exclusion from the modern world of finance. This dissertation challenges this doubly binary conceptualization and locates the myriad views and uses of credit and debt in one conceptual frame. It shows that credit and debt relations were constitutive of various aspects of urban life, including multi-racial neighborhood sub-communities, respectable identities, urban membership and belonging, urban livelihoods and entrepreneurship, and urban planning and governance. The Kariakoo neighborhood in Dar es Salaam serves as the locus to examine how debt and credit shaped work and business, social and communal life, and people’s identities and subjectivities in urban Africa. -

Practicing Subalternity? Nyerere's Tanzania, the Dar School, and Postcolonial Geopolitical Imaginations Jo Sharp

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 Practicing Subalternity? Nyerere's Tanzania, the Dar School, and Postcolonial Geopolitical Imaginations Jo Sharp Tariq Jazeel and Stephen Legg eds. (2019) Subaltern Geographies. Athens: University of Georgia Press Following Tanganyikan independence in 1961, and especially during the period after the announcement of Tanzania's intention to follow an independent path of African socialism after the Arusha Declaration in 1967, Julius Nyerere challenged the geopolitics of colonialism and the Cold War. Like many other Third World leaders at the time, he sought a voice for those previously marginalized from the imaginings of the world order and proposed an alternative geographical imagination of a united Africa and an alliance of the poor. This chapter will explore the challenges faced by Nyerere in trying to practice his postcolonial vision as the leader of a state that came into being on the lower echelons of the postwar world order. Subaltern studies, of course, emerged from scholars in the Indian subcontinent. However, while postcolonial African leaders focused on the neocolonial political and economic entanglements that the new states found themselves caught up in, these were not discussed in isolation from questions of the agency of new states and their people and of the politics of representation and epistemic power, more characteristic of subaltern studies. After all, Nyerere was effectively seeking to find a voice for those marginalized within a world order that actively sought to silence those in the South and that he felt was structured in such a way that it would ensure their continued economic, political, and epistemological marginality. -

Did They Work for Us? Assessing Two Years of Bunge Data 2010-2012

Did they work for us? Assessing two years of Bunge data 2010-2012 1. Introduction The ninth session of the Bunge (Parliament) was adjourned on 9 November 2012, two years since the commencement of the first session on 9 November 2010 following the general election. These Bunge sessions have been broadcast through private and public TV stations allowing citizens to follow their representatives’ actions. Another source of information regarding MP performance is provided by the Parliamentary On-line Information System (POLIS) posted on the Tanzania Parliament website (www.bunge.go.tz) An important question for any citizen is: how did my MP represent my interests in Parliament? One way to assess performance of MPs is to look at the number of interventions they make in Bunge. MPs can make three types of interventions: they can ask basic questions submitted in advance; they can add supplementary questions after basic questions have been answered by the government; or they can makecontributions during the budget sessions, law amendments or discussions on new laws. This brief presents six facts on the performance of MPs, from November 2010 to November 2012, updating similar analyses conducted by Twaweza in previous years. It includes an assessment of who were the least and most active MPs. It also raises questions on the significance of education level when it comes to effectiveness of participation by MPs in parliament. The dataset can be downloaded from www.twaweza.org/go/bunge2010-2012 The Bunge dataset includes observations on 351 members: MPs who were elected and served (233), MPs in Special Seats (102), Presidential Appointees (10) and those from the Zanzibar House of Representatives (5) and the Attorney General.