Technological Adaptation in a Global Conflict: the British Army and Communications Beyond the Western Front, 1914-1918

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100 YEAR COMMEMORATION of the GALLIPOLI CAMPAIGN Go To

HOME / FRONT 100 YEAR COMMEMORATION OF THE GALLIPOLI CAMPAIGN Go to www.penrithregionalgallery.org to download a copy of this Digital Catalogue HOME / FRONT INTRODUCTION The 100 year anniversary of the 25 April 1915 landing As the basis for her drawings, the artist researched and commencement of battle at ANZAC Cove, Gallipoli, and chose historical photographs from the collection of presents a very special opportunity for Australians to reflect the Australian War Memorial. Additional research saw upon conflict, sacrifice and service across the intervening O’Donnell travel to Turkey in March of 2014 to meet with years. historians, visit war museums ,ANZAC battle sites and to survey the terrain and imagine herself and others upon the As a public gallery, concerned to present exhibitions peninsula’s rocky landscape of hell in1915. Imagining what relevant to its community, Penrith Regional Gallery & happened to Australian countrymen and women so far from The Lewers Bequest was keen to make a meaningful home, fighting Turkish soldiers in defence of their homeland contribution to this anniversary. Albeit, so much had been as a consequence of old world geopolitical arrangements, said and written of the Campaign, of its failures, of the old was a difficult and melancholic task. men who led from a safe distance, and of the bravery of the young who fought, the question hovered - “What was left to As the artist walked the scarred earth she found scattered say?” relics of war - pieces of spent shrapnel, fragments of barbed wire, bone protruding from the earth, trenches, now After much consideration we have chosen to devote our worn and gentle furrows, the rusting, hulking, detritus of the Main Gallery Autumn exhibition to an examination of the world’s first modern war. -

Antigua and Barbuda an Annotated Critical Bibliography

Antigua and Barbuda an annotated critical bibliography by Riva Berleant-Schiller and Susan Lowes, with Milton Benjamin Volume 182 of the World Bibliographical Series 1995 Clio Press ABC Clio, Ltd. (Oxford, England; Santa Barbara, California; Denver, Colorado) Abstract: Antigua and Barbuda, two islands of Leeward Island group in the eastern Caribbean, together make up a single independent state. The union is an uneasy one, for their relationship has always been ambiguous and their differences in history and economy greater than their similarities. Barbuda was forced unwillingly into the union and it is fair to say that Barbudan fears of subordination and exploitation under an Antiguan central government have been realized. Barbuda is a flat, dry limestone island. Its economy was never dominated by plantation agriculture. Instead, its inhabitants raised food and livestock for their own use and for provisioning the Antigua plantations of the island's lessees, the Codrington family. After the end of slavery, Barbudans resisted attempts to introduce commercial agriculture and stock-rearing on the island. They maintained a subsistence and small cash economy based on shifting cultivation, fishing, livestock, and charcoal-making, and carried it out under a commons system that gave equal rights to land to all Barbudans. Antigua, by contrast, was dominated by a sugar plantation economy that persisted after slave emancipation into the twentieth century. Its economy and goals are now shaped by the kind of high-impact tourism development that includes gambling casinos and luxury hotels. The Antiguan government values Barbuda primarily for its sparsely populated lands and comparatively empty beaches. This bibliography is the only comprehensive reference book available for locating information about Antigua and Barbuda. -

Battle Management Language: History, Employment and NATO Technical Activities

Battle Management Language: History, Employment and NATO Technical Activities Mr. Kevin Galvin Quintec Mountbatten House, Basing View, Basingstoke Hampshire, RG21 4HJ UNITED KINGDOM [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is one of a coordinated set prepared for a NATO Modelling and Simulation Group Lecture Series in Command and Control – Simulation Interoperability (C2SIM). This paper provides an introduction to the concept and historical use and employment of Battle Management Language as they have developed, and the technical activities that were started to achieve interoperability between digitised command and control and simulation systems. 1.0 INTRODUCTION This paper provides a background to the historical employment and implementation of Battle Management Languages (BML) and the challenges that face the military forces today as they deploy digitised C2 systems and have increasingly used simulation tools to both stimulate the training of commanders and their staffs at all echelons of command. The specific areas covered within this section include the following: • The current problem space. • Historical background to the development and employment of Battle Management Languages (BML) as technology evolved to communicate within military organisations. • The challenges that NATO and nations face in C2SIM interoperation. • Strategy and Policy Statements on interoperability between C2 and simulation systems. • NATO technical activities that have been instigated to examine C2Sim interoperation. 2.0 CURRENT PROBLEM SPACE “Linking sensors, decision makers and weapon systems so that information can be translated into synchronised and overwhelming military effect at optimum tempo” (Lt Gen Sir Robert Fulton, Deputy Chief of Defence Staff, 29th May 2002) Although General Fulton made that statement in 2002 at a time when the concept of network enabled operations was being formulated by the UK and within other nations, the requirement remains extant. -

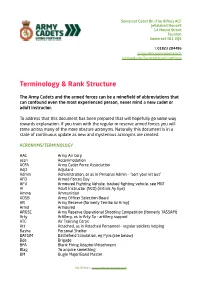

Terminology & Rank Structure

Somerset Cadet Bn (The Rifles) ACF Jellalabad HouseS 14 Mount Street Taunton Somerset TA1 3QE t: 01823 284486 armycadets.com/somersetacf/ facebook.com/SomersetArmyCadetForce Terminology & Rank Structure The Army Cadets and the armed forces can be a minefield of abbreviations that can confound even the most experienced person, never mind a new cadet or adult instructor. To address that this document has been prepared that will hopefully go some way towards explanation. If you train with the regular or reserve armed forces you will come across many of the more obscure acronyms. Naturally this document is in a state of continuous update as new and mysterious acronyms are created. ACRONYMS/TERMINOLOGY AAC Army Air Corp accn Accommodation ACFA Army Cadet Force Association Adjt Adjutant Admin Administration, or as in Personal Admin - “sort your kit out” AFD Armed Forces Day AFV Armoured Fighting Vehicle, tracked fighting vehicle, see MBT AI Adult Instructor (NCO) (initials Ay Eye) Ammo Ammunition AOSB Army Officer Selection Board AR Army Reserve (formerly Territorial Army) Armd Armoured AROSC Army Reserve Operational Shooting Competition (formerly TASSAM) Arty Artillery, as in Arty Sp - artillery support ATC Air Training Corps Att Attached, as in Attached Personnel - regular soldiers helping Basha Personal Shelter BATSIM Battlefield Simulation, eg Pyro (see below) Bde Brigade BFA Blank Firing Adaptor/Attachment Blag To acquire something BM Bugle Major/Band Master 20170304U - armycadets.com/somersetacf Bn Battalion Bootneck A Royal Marines Commando -

A History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference To

The History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference to the Command of Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier by Michael Anthony Taylor A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract 119 Brigade, 40th Division, had an unusual origin as a ‘left-over’ brigade of the Welsh Army Corps and was the only completely bantam formation outside 35th Division. This study investigates the formation’s national identity and demonstrates that it was indeed strongly ‘Welsh’ in more than name until 1918. New data on the social background of men and officers is added to that generated by earlier studies. The examination of the brigade’s actions on the Western Front challenges the widely held belief that there was an inherent problem with this and other bantam formations. The original make-up of the brigade is compared with its later forms when new and less efficient units were introduced. -

Wire August 2013

THE wire August 2013 www.royalsignals.mod.uk The Magazine of The Royal Corps of Signals HONOURS AND AWARDS We congratulate the following Royal Signals personnel who have been granted state honours by Her Majesty The Queen in her annual Birthday Honours List: Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) Maj CN Cooper Maj RJ Craig Lt Col MS Dooley Maj SJ Perrett Queen’s Volunteer Reserves Medal (QVRM) Lt Col JA Allan, TD Meritorious Service Medal WO1 MP Clish WO1 PD Hounsell WO2 SV Reynolds WO2 PM Robins AUGUST 2013 Vol. 67 No: 4 The Magazine of the Royal Corps of Signals Established in 1920 Find us on The Wire Published bi-monthly Annual subscription £12.00 plus postage Editor: Mr Keith Pritchard Editor Deputy Editor: Ms J Burke Mr Keith Pritchard Tel: 01258 482817 All correspondence and material for publication in The Wire should be addressed to: The Wire, RHQ Royal Signals, Blandford Camp, Blandford Forum, Dorset, DT11 8RH Email: [email protected] Contributors Deadline for The Wire : 15th February for publication in the April. 15th April for publication in the June. 15th June for publication in the August. 15th August for publication in the October. 15th October for publication in the December. Accounts / Subscriptions 10th December for publication in the February. Mrs Jess Lawson To see The Wire on line or to refer to Guidelines for Contributors, go to: Tel: 01258 482087 http://www.army.mod.uk/signals/25070.aspx Subscribers All enquiries regarding subscriptions and changes of address of The Wire should be made to: 01258 482087 or 94371 2087 (mil) or [email protected]. -

Milnesdickonjohn2000mahist.Pdf (11.58Mb)

THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PROTECTION OF AUTHOR ’S COPYRIGHT This copy has been supplied by the Library of the University of Otago on the understanding that the following conditions will be observed: 1. To comply with s56 of the Copyright Act 1994 [NZ], this thesis copy must only be used for the purposes of research or private study. 2. The author's permission must be obtained before any material in the thesis is reproduced, unless such reproduction falls within the fair dealing guidelines of the Copyright Act 1994. Due acknowledgement must be made to the author in any citation. 3. No further copies may be made without the permission of the Librarian of the University of Otago. August 2010 IMPERIAL SOLDIERS? THE NEW ZEALAND MOUNTED RIFLES BRIGADE IN SINAI AND PALESTINE 1916-1919 D. JOHN MILNES A thesis submitted for the degree of Masters of Arts in History at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand 1999. ll Abstract New Zealanders served in large numbers in three campaigns during the Great War of 1914-1918. Much has been written by historians, both past and present, about the experiences of the soldiers in two of these campaigns: Gallipoli and the Western Front. The third of these campaigns, Sinai and Palestine, is perhaps the least well known of New Zealand's Great War war efforts, but probably the most successful. This thesis is an investigation of how Imperial the New Zealanders who served in the Mounted Rifles brigade were. By this it 1s meant; were the soldiers characteristic of the British Empire, its institutions, and its ethos? Or were they different, reflecting distinctly New Zealand ideals and institutions? Central to this investigation were the views and opinions held by the New Zealand soldiers who served in the Mounted Rifles brigade in Sinai and Palestine from 1916-1919 regarding the British Empire. -

Index Dummy Thru Vol 103.Indd

of the Indian Reorganization Act, 7(1):48, 8(1):9, 9(1):19, 10(1):48, A 93(4):200 11(1):39 Abbott, Lawrence F., “New York and Astoria,” Aberdeen Timber Worker, 100(3):139 “A. B. Chamberlin: The Illustration of Seattle 18(1):21-24 Aberdeen World, 35(3):228, 66(1):3, 5, 7, 9, 11 Architecture, 1890-1896,” by Jeffrey Abbott, Margery Post, Planning a New West: Abernethy, Alexander S., 13(2):132, 20(2):129, Karl Ochsner, 81(4):130-44 The Columbia River Gorge National 131 A. B. Rabbeson and Company, 36(3):261-63, Scenic Area, review, 89(3):151-52 correspondence of, 11(1):79, 48(3):87 267 Abbott, Newton Carl, Montana in the Making, as gubernatorial candidate, 42(1):10-13, A. F. Kashevarov’s Coastal Explorations in 22(3):230, 24(1):66 28, 43(2):118 Northwest Alaska, 1838, ed. James W. Abbott, T. O., 30(1):32-35 tax problems of, 79(2):61 VanStone, review, 70(4):182 Abbott, Wilbur Cortez, The Writing of History, Wash. constitution and, 8(1):3, 9(2):130- A. H. Reynolds Bank (Walla Walla), 25(4):245 18(2):147-48 52, 9(3):208-29, 9(4):296-307, A. L. Brown Farm (Nisqually Flats, Wash.), Abby Williams Hill and the Lure of the West, by 10(2):140-41, 17(1):30 71(4):162-71 Ronald Fields, review, 81(2):75 Abernethy, Clark and Company, 48(3):83-87 “A. L. White, Champion of Urban Beauty,” by Abel, Alfred M., 39(3):211 Abernethy, George, 1(1):42-43, 45-46, 48, John Fahey, 72(4):170-79 Abel, Annie Heloise (Annie Heloise Abel- 15(4):279-82, 17(1):48, 21(1):47, A. -

GIPE-010851.Pdf

Dhananjayarao Gadgil Library l~mnWIIIIID GIPE-PUNE-OI0851 SHIPS AND SEAMEN THE HOME UNIVERSITY LIB~ARY OF MODERN KNOWLEDGE Editor. of THE HOME UNIVERSITY UBRARY OF MODERN KNO~E RT. HON. H. A. L. FIsHER. F.R.S., LL.D., D.LITr. PRo)'. GILBERT MUBllAY, F.B.A., LL.D., 'D.LnT. PRO),. Jl1LL\N S. HUXLEY, M.A. For ,.. oj tlOlumu '" 1M LiImwr _ end of book. SHIPS & SEAMEN 11J GEOFFREY RAWSON AlIl1Ior 0/ .. ADMIRAL BBATTY," II ADMIRAL BLIGH," .. ADMIRAL RAWSON." etc. LONDON Thornton Butterworth Ltd. XL125·3.N~ Ct1 \ 0'05\ AU Rip" IU-.l ....,. AJID 1'IIl....... GDAI' JIIII'I.r.d CONTENTS CHAP. PAGE I. TUE RISE OF STEAM 7 II. THE GREAT DAYS OF SAIL 30 III. THE HEROIC AGE-JAMES COOK 46 IV. SAILING DIRECTIONS 66 V. THE MIRROR OF THE SEA 90 VI. SHIPS AND SHIPPING 104 VII. TRADE ROUTES II4 VIII. SAFETY AT SEA 123 IX. AIDS TO NAVIGATION 142 X. THE MASTER AND THE MARINERS • 159 XI. THE BUSINESS OF SHIPPING 179 XII. THE SEAMAN AND HIS SHIP • 202 XIII. THE REGULATION OF SHIPPING 222 ApPENDIX 247 BIBLIOGRAPHY 250 INDEX 252 5 CHAPTER I THE RISE OF STEAM ON a summer's afternoon in the month of July, 1843, there was much excitement in the ancient seaport of Bristol. The city was gay with flags, and crowds lined the streets lead ing to the waterside where a large concourse had assembled to witness the launching of the iron screw steamer, Great Britain, by the Prince Consort. A public holiday had been proclaimed, and there was disappointment when, the ship having been duly launched, it was found that the dock gates through which she was to pass were too small to allow her exit. -

South African Forces in the British Army

From the page: The Long, Long Trail The British Army in the Great War of 1914-1918 South African forces in the British Army In 1902, just twelve years before Great Britain declared war, the armies of Britain and the Boer Republics (Transvaal and Orange Free State) had been fighting each other in the Second Boer War. There had been an extraordinary transformation in relationships between the countries in the intervening period and the Union of South Africa was to prove a staunch and hard-fighting Ally. Here is a summary of their story: South Africa enters the war on British side; some Boer conservatives rebel In August 1914 Louis Botha and Jan Smuts took the Union of South Africa into the war in support of Great Britain. Louis Botha, former member of the Transvaal Volksraad and an accomplished leader of Boer forces against the British in 1899-1902 had been elected the first President of the Union of South Africa in 1910. Jan Christian Smuts, another former Boer military leader, was his Minister of Defence. Both men had worked for increased harmony between South Africa and Britain since the end of the war in 1902. They now considered that South Africa, as a British dominion, must support the British side. They quickly ordered troops into German protectorate of South-West Africa. Many Afrikaners opposed going to war with Germany, which had aided them during the war against Britain (and continued a quiet propaganda war ever since). An attempted Boer coup against Botha's government failed in September 1914 when Christiaan Beyer - an Afrikaner hero from the earlier war - was killed by police, and a large armed uprising in the Orange Free State and the Transvaal later in the year was also held. -

Thelast Charge

The Last Charge An exhibition at the Buckinghamshire County Museum, Church Street, Aylesbury, HP20 2QP to commemorate the centenary of the last great British cavalry charges at El Mughar, Palestine on 13 November 1917. 31 October 2017 – 5 January 2018 Buckinghamshire Military Museum Trust www.bmmt.co.uk Buckinghamshire County Museum www.buckscountymuseum.org The Buckinghamshire Military Museum Trust gratefully acknowledges the support of the following without which this exhibition could not have been held: The Last Charge Buckinghamshire County Museum The charge of the 6th Mounted Brigade at El Mughar in Palestine on 13 November 1917 can claim to be the last great British cavalry charge although Lord Parmoor there were later charges in Syria in 1918 by an Indian regiment and by the The Crown Commissioners and BNP Paribas Australian Light Horse. The Institute of Directors Significantly, James Prinsep Beadle was commissioned to paint the charge at El Mughar as the cavalry contribution to a representative collection of Sir Evelyn de Rothschild and the Rothschild Archive Great War studies for the United Services Club in Pall Mall. Never previously The Centre for Buckinghamshire Studies exhibited outside of the building, which now houses the Institute of Directors, Beadle’s painting depicts ‘B’ Squadron of the 1/1st Royal Bucks The Buckingham Heritage Trust Hussars leading the charge against the Ottoman Turkish defenders. The regiment was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel the Hon. Fred Cripps, later The National Army Museum Lord Parmoor. The charge, which also featured the 1/1st Dorset Yeomanry The Berkshire Yeomanry Museum Trust with the 1/1st Berkshire Yeomanry in support, was described by General Sir George Barrow as ‘a complete answer to the critics of the mounted arm’. -

British, African and Indian Infantry Battalions This Edition Dated: 25Th July 2013 ISBN

2013 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER A CONCISE OVERVIEW OF: BRITISH, AFRICAN & INDIAN INFANTRY BATTALIONS A concise overview of the organization, establishment, structure, roles, responsibilities and weapons of a British, African and Indian Infantry Battalion during the Second World War. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2013) 25 July 2013 [BRITISH, AFRICAN & INDIAN INFANTRY BATTALIONS] A Concise Overview of British, African and Indian Infantry Battalions This edition dated: 25th July 2013 ISBN All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means including; electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, scanning without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Author: Robert PALMER (copyright held by author) Published privately by: Robert PALMER www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk 1 25 July 2013 [BRITISH, AFRICAN & INDIAN INFANTRY BATTALIONS] Contents Pages Introduction 3 British Infantry Battalions 4 – 12 Standard Infantry Battalion 4 – 6 Medium Machine Gun Battalion 6 – 7 Motor Battalion 7 – 8 Lorried Infantry Battalion 8 – 10 Parachute Battalion 10 Airlanding Battalion 10 – 12 British African Infantry Battalions 13 – 14 British Indian Infantry Battalions 15 – 16 Battalion Headquarters 17– 21 Headquarter Company 22 Support Company 22 – 23 Signals Platoon 23 – 25 Anti-Aircraft Platoon 26 Anti-Tank Platoon 26 – 29 Mortar Platoon 29 – 31 Carrier Platoon 31 – 34 Pioneer Platoon 34 – 35 Administrative Platoon 35 – 37 The Rifle Company 37 – 39 Operations 39 – 41 The Sniper 42 – 43 Infantry Weapons 44 – 47 Markings 48 – 49 Bibliography and Sources 50 – 54 2 25 July 2013 [BRITISH, AFRICAN & INDIAN INFANTRY BATTALIONS] Introduction The Battalion was the key unit within the structure of the British Army and the British Indian Army.