British, African and Indian Infantry Battalions This Edition Dated: 25Th July 2013 ISBN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Journal of Homelessness

European Observatory on Homelessness European Observatory on Homelessness European Journal European Journal of Homelessness Homelessness of Homelessness The European Journal of Homelessness provides a critical analysis of policy and practice on homelessness in Europe for policy makers, practitioners, researchers and academics. The aim is to stimulate debate on homelessness and housing exclusion at the Journalof European level and to facilitate the development of a stronger evidential base for policy development and innovation. The journal seeks to give international exposure to significant national, regional and local developments and to provide a forum for comparative analysis of policy and practice in preventing and tackling home- lessness in Europe. The journal will also assess the lessons for European Europe which can be derived from policy, practice and research from elsewhere. European Journal of Homelessness is published twice a year by FEANTSA, the European Federation of National Organisations working with the Homeless. An electronic version can be down- loaded from FEANTSA’s website www.feantsaresearch.org. FEANTSA works with the European Commission, the contracting authority for the four-year partnership agreement under which this publication has received funding. The information contained in this publication does not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission. n _ May 2017 Volume 11, No. 1 _ May 2017 ISSN: 2030-2762 (Print) 2030-3106 (Online) n European Federation of National Associations Working with the Homeless AISBL Fédération Européenne d’Associations Nationales Travaillant avec les Sans-Abri AISBL 194, Chaussée de Louvain n 1210 Brussels n Belgium Tel.: + 32 2 538 66 69 n Fax: + 32 2 539 41 74 [email protected] n www.feantsaresearch.org Volume 11, No. -

National World War I Museum 2008 Accessions to the Collections Doran L

NATIONAL WORLD WAR I MUSEUM 2008 ACCESSIONS TO THE COLLECTIONS DORAN L. CART, CURATOR JONATHAN CASEY, MUSEUM ARCHIVIST All accessions are donations unless otherwise noted. An accession is defined as something added to the permanent collections of the National World War I Museum. Each accession represents a separate “transaction” between donor (or seller) and the Museum. An accession can consist of one item or hundreds of items. Format = museum accession number + donor + brief description. For reasons of privacy, the city and state of the donor are not included here. For further information, contact [email protected] or [email protected] . ________________________________________________________________________ 2008.1 – Carl Shadd. • Machine rifle (Chauchat fusil-mitrailleur), French, M1915 CSRG (Chauchat- Sutter-Ribeyrolles and Gladiator); made at the Gladiator bicycle factory; serial number 138351; 8mm Lebel cartridge; bipod; canvas strap; flash hider (standard after January 1917); with half moon magazine; • Magazine carrier, French; wooden box with hinged lid, no straps; contains two half moon magazines; • Tool kit for the Chauchat, French; M1907; canvas and leather folding carrier; tools include: stuck case extractor, oil and kerosene cans, cleaning rod, metal screwdriver, tension spring tool, cleaning patch holder, Hotchkiss cartridge extractor; anti-aircraft firing sight. 2008.2 – Robert H. Rafferty. From the service of Cpl. John J. Rafferty, 1 Co 164th Depot Brigade: Notebook with class notes; • Christmas cards; • Photos; • Photo postcard. 2008.3 – Fred Perry. From the service of John M. Figgins USN, served aboard USS Utah : Diary; • Oversize photo of Utah ’s officers and crew on ship. 2008.4 – Leslie Ann Sutherland. From the service of 1 st Lieutenant George Vaughan Seibold, U.S. -

World War Two Squad Makeup

World War Two Squad Makeup Troop Type Rank US Army Rifle Squad / US Army Ranger Squad Squad Leader Sergeant/ Staff Sergeant Assistant Squad Leader Corporal/ Sergeant Scout x 2 Private Rifleman x 5 Private Automatic Rifleman Private Assistant Automatic Rifleman Private Automatic Rifle Ammo Carrier Private US Army Armored Rifle Squad Squad Leader Sergeant/ Staff Sergeant Assistant Squad Leader Corporal/ Sergeant Rifleman x 9 Private Driver Private US Army Heavy Machine Gun Squad Squad Leader Sergeant Machine Gunner Corporal Assistant Machine Gunner Private Machine Gun Ammo Carriers x 3 Private Driver Private US Army Light Machine Gun Squad Squad Leader Sergeant Machine Gunner Private Assistant Machine Gunner Private Machine Gun Ammo Carriers x 2 Private US Army Heavy Mortar Squad Squad Leader Staff Sergeant Mortar Gunner Corporal Assistant Mortar Gunner Private Mortar Ammo Carriers x 4 Private Driver Private US Army Light Mortar Squad Squad Leader Sergeant Mortar Gunner Private Assistant Mortar Gunner Private Mortar Ammo Carriers x 2 Private US Army Armored Anti Tank Squad Squad Leader Staff Sergeant Gunner Corporal Cannoneers x 4 Private Ammunition Carriers x 3 Private Driver Private US Army Airborne Squad Squad Leader Sergeant/ Staff Sergeant Assistant Squad Leader Corporal/ Sergeant Scout x 2 Private Rifleman x 5 Private Machine Gunner Private Assistant Machine Gunner Private Machine Gun Ammo Carrier Private US Army Ranger Assault Squad Squad Leader Sergeant/ Staff Sergeant Assistant Squad Leader Corporal/ Sergeant Rifleman x 5 Private -

List of Exhibits at IWM Duxford

List of exhibits at IWM Duxford Aircraft Airco/de Havilland DH9 (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 82A Tiger Moth (Ex; Spectrum Leisure Airspeed Ambassador 2 (EX; DAS) Ltd/Classic Wings) Airspeed AS40 Oxford Mk 1 (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 82A Tiger Moth (AS; IWM) Avro 683 Lancaster Mk X (AS; IWM) de Havilland DH 100 Vampire TII (BoB; IWM) Avro 698 Vulcan B2 (AS; IWM) Douglas Dakota C-47A (AAM; IWM) Avro Anson Mk 1 (AS; IWM) English Electric Canberra B2 (AS; IWM) Avro Canada CF-100 Mk 4B (AS; IWM) English Electric Lightning Mk I (AS; IWM) Avro Shackleton Mk 3 (EX; IWM) Fairchild A-10A Thunderbolt II ‘Warthog’ (AAM; USAF) Avro York C1 (AS; DAS) Fairchild Bolingbroke IVT (Bristol Blenheim) (A&S; Propshop BAC 167 Strikemaster Mk 80A (CiA; IWM) Ltd/ARC) BAC TSR-2 (AS; IWM) Fairey Firefly Mk I (FA; ARC) BAe Harrier GR3 (AS; IWM) Fairey Gannet ECM6 (AS4) (A&S; IWM) Beech D17S Staggerwing (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) Fairey Swordfish Mk III (AS; IWM) Bell UH-1H (AAM; IWM) FMA IA-58A Pucará (Pucara) (CiA; IWM) Boeing B-17G Fortress (CiA; IWM) Focke Achgelis Fa-330 (A&S; IWM) Boeing B-17G Fortress Sally B (FA) (Ex; B-17 Preservation General Dynamics F-111E (AAM; USAF Museum) Ltd)* General Dynamics F-111F (cockpit capsule) (AAM; IWM) Boeing B-29A Superfortress (AAM; United States Navy) Gloster Javelin FAW9 (BoB; IWM) Boeing B-52D Stratofortress (AAM; IWM) Gloster Meteor F8 (BoB; IWM) BoeingStearman PT-17 Kaydet (AAM; IWM) Grumman F6F-5 Hellcat (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) Branson/Lindstrand Balloon Capsule (Virgin Atlantic Flyer Grumman F8F-2P Bearcat (FA; Patina Ltd/TFC) -

Organization of the British Infantry Battalion 1938 to 1945

1 Organization of the British Infantry Battalion 1938 to 1945 A www.bayonetstrength.uk PDF 1st draft uploaded 4th August 2018 2nd draft uploaded 2nd June 2019 Amendments include; 1. Updates to Signal Platoon wireless and line equipment (1943 to 1945). 2. Clarification on 6-pdr Anti-tank gun ammunition allocation. 3. Added Annex D on the Assault Pioneer Platoon (1943 to 1945). 4. Correction of a number of lamentable typos… www.bayonetstrength.uk Gary Kennedy August 2018 2 Contents Page i. Introduction 3 ii. British Army Ranks 4 iii. British Infantry Battalion structure and terminology 6 Overview 7 Evolution of the British Infantry Battalion (chart) 9 The elements of the Battalion 10 Annex A - Signal communication 31 Annex B - Weapons and ammunition 39 Annex C - The Lorried Infantry Battalion 49 Annex D - Assault Pioneer Platoon 51 Sources and acknowledgements 52 Still searching for… 55 www.bayonetstrength.uk Gary Kennedy August 2018 3 Introduction This is my attempt at analysing the evolving organization, equipment and weapons of the British Infantry Battalion during the Second World War. It covers three distinct periods in the development of the Infantry Battalion structure; the pre-war reorganization utilised in France in 1940, the campaign in North Africa that expanded into the Mediterranean and the return to Northwest Europe in 1944. What is not included is the British Infantry Battalion in the Far East, as sadly I have never been able to track down the relevant documents for the British Indian Army. As far as possible, the information included here is obtained from contemporary documents, with a list of sources and acknowledgements given at the end. -

The DIY STEN Gun

The DIY STEN Gun Practical Scrap Metal Small Arms Vol.3 By Professor Parabellum Plans on pages 11 to 18 Introduction The DIY STEN Gun is a simplified 1:1 copy of the British STEN MKIII submachine gun. The main differences however include the number of components having been greatly reduced and it's overall construction made even cruder. Using the simple techniques described, the need for a milling machine or lathe is eliminated making it ideal for production in the home environment with very limited tools. For obvious legal reasons, the demonstration example pictured was built as a non-firing display replica. It's dummy barrel consists of a hardened steel spike welded and pinned in place at the chamber end and a separate solid front portion protruding from the barrel shroud for display. It's bolt is also inert with no firing pin. This document is for academic study purposes only. (Disassembled: Back plug, recoil spring, bolt, magazine, sear and trigger displayed) (Non-functioning dummy barrel present on display model) Tools & construction techniques A few very basic and inexpensive power tools can be used to simulate machining actions usually reserved for a milling machine. Using a cheap angle grinder the average hobbyist has the ability to perform speedy removal of steel using a variety of cutting and grinding discs. Rather than tediously using a hacksaw to cut steel sheet, an angle grinder fitted with a 1mm slitting disc will accurately cut a straight line through steel of any thickness in mere seconds. Fitted with a 2mm disc it can be used to easily 'sculpt' thick steel into any shape in a fraction of the time it takes to manually use a hand file. -

Battle Management Language: History, Employment and NATO Technical Activities

Battle Management Language: History, Employment and NATO Technical Activities Mr. Kevin Galvin Quintec Mountbatten House, Basing View, Basingstoke Hampshire, RG21 4HJ UNITED KINGDOM [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is one of a coordinated set prepared for a NATO Modelling and Simulation Group Lecture Series in Command and Control – Simulation Interoperability (C2SIM). This paper provides an introduction to the concept and historical use and employment of Battle Management Language as they have developed, and the technical activities that were started to achieve interoperability between digitised command and control and simulation systems. 1.0 INTRODUCTION This paper provides a background to the historical employment and implementation of Battle Management Languages (BML) and the challenges that face the military forces today as they deploy digitised C2 systems and have increasingly used simulation tools to both stimulate the training of commanders and their staffs at all echelons of command. The specific areas covered within this section include the following: • The current problem space. • Historical background to the development and employment of Battle Management Languages (BML) as technology evolved to communicate within military organisations. • The challenges that NATO and nations face in C2SIM interoperation. • Strategy and Policy Statements on interoperability between C2 and simulation systems. • NATO technical activities that have been instigated to examine C2Sim interoperation. 2.0 CURRENT PROBLEM SPACE “Linking sensors, decision makers and weapon systems so that information can be translated into synchronised and overwhelming military effect at optimum tempo” (Lt Gen Sir Robert Fulton, Deputy Chief of Defence Staff, 29th May 2002) Although General Fulton made that statement in 2002 at a time when the concept of network enabled operations was being formulated by the UK and within other nations, the requirement remains extant. -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

Heroics & Ros Index

MBW - ARMOURED RAIL CAR Page 6 Error! Reference source not found. Page 3 HEROICS & ROS WINTER 2009 CATALOGUE Napoleonic American Civil War Page 11 Page 12 INDEX Land , Naval & Aerial Wargames Rules 1 Books 1 Trafalgar 1/300 transfers 1 HEROICS & ROS 1/300TH SCALE W.W.1 Aircraft 1 W.W.1 Figures and Vehicles 4 W.W.2 Aircraft 2 W.W.2. Tanks &Figures 4 W.W.2 Trains 6 Attack & Landing Craft 6 SAMURAI Page11 Modern Aircraft 3 Modern Tanks & Figures 7 NEW KINGDOM EGYPTIANS, Napoleonic, Ancient Figures 11 HITTITES AND Dark Ages, Medieval, Wars of the Roses, SEA PEOPLES Renaissance, Samurai, Marlburian, Page 11 English Civil War, Seven Years War, A.C.W, Franco-Prussian War and Colonial Figures 12 th Revo 1/300 full colour Flags 12 VIJAYANTA MBT Page 7 SWA103 SAAB J 21 Page 4 World War 2 Page 4 PRICE Mk 1 MOTHER Page 4 £1.00 Heroics and Ros 3, CASTLE WAY, FELTHAM, MIDDLESEX TW13 7NW www.heroicsandros.co.uk Welcome to the new home of Heroics and Ros models. Over the next few weeks we will be aiming to consolidate our position using the familiar listings and web site. However, during 2010 we will be bringing forward some exciting new developments both in the form of our web site and a modest expansion in our range of 1/300 scale vehicles. For those wargamers who have in the past purchased their Heroics and Ros models along with their Navwar 1/300 ships, and Naismith and Roundway 15mm figures, these ranges are of course still available direct from Navwar www.navwar.co.uk as before, though they will no longer be carrying the Heroics range. -

REFERENCE BOOK Table of Contents Designer’S Notes

REFERENCE BOOK Table of Contents Designer’s Notes ............................................................ 2 31.0 Mapmaker’s Notes ................................................. 40 26.0 Footnoted Entries ........................................... 2 32.0 Order of Battle ....................................................... 41 27.0 Game Elements .............................................. 13 33.0 Selected Sources & Recommended Reading ......... 48 28.0 Units & Weapons ........................................... 21 29.0 OB Notes ....................................................... 33 30.0 Historical Notes ............................................. 39 GMT Games, LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 www.GMTGames.com 2 Operation Dauntless Reference Book countryside characterized by small fields rimmed with thick and Designer’s Notes steeply embanked hedges and sunken roads, containing small stout I would like to acknowledge the contributions of lead researchers farms with neighbouring woods and orchards in a broken landscape. Vincent Lefavrais, A. Verspeeten, and David Hughes to the notes Studded with small villages, ideal for defensive strongpoints…” appearing in this booklet, portions of which have been lifted rather 6 Close Terrain. There are few gameplay differences between close liberally from their emails and edited by myself. These guys have terrain types. Apart from victory objectives, which are typically my gratitude for a job well done. I’m very pleased that they stuck village or woods hexes, the only differences are a +1 DRM to Re- with me to the end of this eight-year project. covery rolls in village hexes, a Modifier Chit which favors village and woods over heavy bocage, and a higher MP cost to enter woods. Furthermore, woods is the only terrain type that blocks LOS with 26.0 Footnoted Entries respect to spotting units at higher elevation. For all other purposes, close terrain is close terrain. -

Christmas Party Minutes, 13 December, 2017 Inside This Issue

Vol. 9, No. 1 Published by AMPS Central South Carolina January, 2018 Welcome to the latest issue of our newsletter. We try Inside This Issue REALLY hard to publish this each month, but sometimes stuff happens, or you know, CRS flair ups occur. Of Meeting Minutes....................1-5Minutes....................1-4 course, what’s published in this newsletter is probably out of date, known by everyone already, or completely off-topic. Maybe everyone will like the pretty colors, but Upcoming Events..................5-7Events..................5-8Events.................N/A then your ink cartridge will probably run out after only printing a couple pages. This paragraph is what’s known New Releases..........................8Releases.......................5-6Releases.......................8-9 as “filler text”, which we needed since we added the snazzy table of contents and this area was kind of Members Build Blogs...........9-10Blogs…............9Blogs….........6-7 empty. Check out the “Classified Ad” section near the end of Club “Contest”………............N/A“Contest”……...............N/A the newsletter. This section will give you a space to advertise items you want to barter, swap, sale or trade. NewInteresting Techniques…...............N/A Articles.............10-23 Or even a request for research material. Check it out. Contact the seller directly. Note personal email InterestingNew Techniques……............N/A Articles.............10-14Articles...............7-13 addresses are not listed on the public site. Contact the seller directly via his/her -

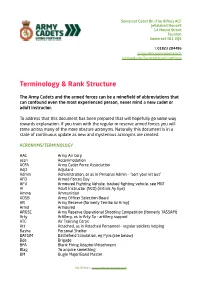

Terminology & Rank Structure

Somerset Cadet Bn (The Rifles) ACF Jellalabad HouseS 14 Mount Street Taunton Somerset TA1 3QE t: 01823 284486 armycadets.com/somersetacf/ facebook.com/SomersetArmyCadetForce Terminology & Rank Structure The Army Cadets and the armed forces can be a minefield of abbreviations that can confound even the most experienced person, never mind a new cadet or adult instructor. To address that this document has been prepared that will hopefully go some way towards explanation. If you train with the regular or reserve armed forces you will come across many of the more obscure acronyms. Naturally this document is in a state of continuous update as new and mysterious acronyms are created. ACRONYMS/TERMINOLOGY AAC Army Air Corp accn Accommodation ACFA Army Cadet Force Association Adjt Adjutant Admin Administration, or as in Personal Admin - “sort your kit out” AFD Armed Forces Day AFV Armoured Fighting Vehicle, tracked fighting vehicle, see MBT AI Adult Instructor (NCO) (initials Ay Eye) Ammo Ammunition AOSB Army Officer Selection Board AR Army Reserve (formerly Territorial Army) Armd Armoured AROSC Army Reserve Operational Shooting Competition (formerly TASSAM) Arty Artillery, as in Arty Sp - artillery support ATC Air Training Corps Att Attached, as in Attached Personnel - regular soldiers helping Basha Personal Shelter BATSIM Battlefield Simulation, eg Pyro (see below) Bde Brigade BFA Blank Firing Adaptor/Attachment Blag To acquire something BM Bugle Major/Band Master 20170304U - armycadets.com/somersetacf Bn Battalion Bootneck A Royal Marines Commando