This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached Copy Is Furnished to the Author for Internal Non-Commerci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embryophytic Sporophytes in the Rhynie and Windyfield Cherts

Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences http://journals.cambridge.org/TRE Additional services for Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Embryophytic sporophytes in the Rhynie and Windyeld cherts Dianne Edwards Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences / Volume 94 / Issue 04 / December 2003, pp 397 - 410 DOI: 10.1017/S0263593300000778, Published online: 26 July 2007 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0263593300000778 How to cite this article: Dianne Edwards (2003). Embryophytic sporophytes in the Rhynie and Windyeld cherts. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences, 94, pp 397-410 doi:10.1017/S0263593300000778 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TRE, IP address: 131.251.254.13 on 25 Feb 2014 Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences, 94, 397–410, 2004 (for 2003) Embryophytic sporophytes in the Rhynie and Windyfield cherts Dianne Edwards ABSTRACT: Brief descriptions and comments on relationships are given for the seven embryo- phytic sporophytes in the cherts at Rhynie, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. They are Rhynia gwynne- vaughanii Kidston & Lang, Aglaophyton major D. S. Edwards, Horneophyton lignieri Barghoorn & Darrah, Asteroxylon mackiei Kidston & Lang, Nothia aphylla Lyon ex Høeg, Trichopherophyton teuchansii Lyon & Edwards and Ventarura lyonii Powell, Edwards & Trewin. The superb preserva- tion of the silica permineralisations produced in the hot spring environment provides remarkable insights into the anatomy of early land plants which are not available from compression fossils and other modes of permineralisation. -

Additional Observations on Zosterophyllum Yunnanicum Hsü from the Lower Devonian of Yunnan, China

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/77818/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Edwards, Dianne, Yang, Nan, Hueber, Francis M. and Li, Cheng-Sen 2015. Additional observations on Zosterophyllum yunnanicum Hsü from the Lower Devonian of Yunnan, China. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 221 , pp. 220-229. 10.1016/j.revpalbo.2015.03.007 file Publishers page: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2015.03.007 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2015.03.007> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. @’ Additional observations on Zosterophyllum yunnanicum Hsü from the Lower Devonian of Yunnan, China Dianne Edwardsa, Nan Yangb, Francis M. Hueberc, Cheng-Sen Lib a*School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3AT, UK b Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China cNational Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 20560-0121, USA * Corresponding author, Tel.: +44 29208742564, Fax.: +44 2920874326 E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Investigation of unfigured specimens in the original collection of Zosterophyllum yunnanicum Hsü 1966 from the Lower Devonian (upper Pragian to basal Emsian) Xujiachong Formation, Qujing District, Yunnan, China has provided further data on both sporangial and stem anatomy. -

Lepidoptera) from Siberia and the Russian Far East, with Descriptions of Two New Species·

© Entomologica Fennica. 20 September 1996 lncurvariidae and Prodoxidae (Lepidoptera) from Siberia and the Russian Far East, with descriptions of two new species· Mikhail V. Kozlov Kozlov, M.V. 1996: Incurvariidae and Prodoxidae (Lepidoptera) from Siberia and the Russian Far East, with descriptions of two new species - Entomol. Fennica 7:55-62. The Incurvariidae and Prodoxidae of eastern Russia total 19 species in eight genera. Phylloporia bistrigella (Haworth), now reported from Yukon, is tentatively included in the list, although it has not yet been discovered in the Eastern Palaearctic. Four species previously known only from Europe, lncurvaria vetulella (Zetterstedt), I. circulella (Zetterstedt), Lampronia luzella (Hubner), and L. provectella (Heyden) are reported from Siberia; lncurvaria kivatshella Kutenkova is synonymized with 1. vetulella. Lampronia sakhalinella sp. n. is described from Sakhalin. L. altaica Zagulajev is reported from North Korea; the female postabdomen and genitalia of this species are described and figured. The genus Greya Busck, previously known only from North America, is reported from the Palaearctic, with G. variabilis Davis & Pellmyr and G. kononenkoi sp. n. recorded from the Chukchi Peninsula, and G. marginimacu lata (Issiki) comb. n. originally described from Japan is expected from the Russian Far East. Among the nine species not known from Europe, one species is reported from Altai only; two show a Beringian distribution; six species are associated with the southern areas of the Far East and Japan, and one is distributed from the Irkutsk region to Sakhalin and Primorye. Mikhail V. Kozlov, Laboratory of Ecological Zoology, University of Turku, FIN-20500 Turku, Finland Received 23 February 1994, accepted 2 November 1995 1. -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Revisión De La Familia Cerambycidae (Insecta: Coleoptera) En La Colección Entomológica De La Escuela Nacional De Ciencias Biológicas

SISTEMÁTICA Y MORFOLOGÍA ISSN: 2448-475X REVISIÓN DE LA FAMILIA CERAMBYCIDAE (INSECTA: COLEOPTERA) EN LA COLECCIÓN ENTOMOLÓGICA DE LA ESCUELA NACIONAL DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS Ricardo Alan Cruz-Cuevas y Luis Javier Víctor-Rosas Laboratorio de Entomología, Departamento de Zoología, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Prolongación de Carpio y Plan de Ayala, Col. Santo Tomás, Del. Miguel Hidalgo, C. P. 11340, Ciudad de México. Autor de correspondencia: [email protected] RESUMEN. La familia Cerambycidae es una de las más diversas dentro del orden Coleoptera, a pesar de lo cual no se cuenta con estudios suficientes sobre este grupo en México. Dentro de las colecciones nacionales que cuentan con ejemplares de la familia, se encuentra la colección entomológica de la Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas (ENCB). En el presente trabajo, se efectuó la revisión del material de este taxón depositado en la colección entomológica de la ENCB para aportar información adicional al conocimiento de los cerambícidos mexicanos. Se examinaron 442 ejemplares pertenecientes a seis subfamilias, 38 tribus y 49 géneros. La subfamilia mejor representada fue Cerambycinae (11 tribus y 20 géneros), siguiéndole Lamiinae (nueve tribus y 16 géneros) y Prioninae (siete tribus y 11 géneros), mientras que Parandrinae, Lepturinae y Necydalinae cuentan con un solo género en cada caso. Dentro de las tribus revisadas, la más abundante y diversa fue Trachyderini (Cerambycinae), y el generó más abundante fue Tylosis, perteneciente a esta tribu. Los estados mejor representados en cuanto a número de ejemplares son el Estado de México y Morelos, mientras que los estados con mayor variedad de géneros son el Estado de México, Veracruz, Morelos, Chiapas, Oaxaca y Guerrero. -

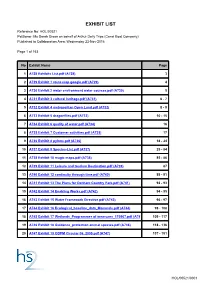

Exhibit List

EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 1 of 163 No Exhibit Name Page 1 A728 Exhibits List.pdf (A728) 3 2 A729 Exhibit 1 route map google.pdf (A729) 4 3 A730 Exhibit 2 water environment water courses.pdf (A730) 5 4 A731 Exhibit 3 cultural heritage.pdf (A731) 6 - 7 5 A732 Exhibit 4 metropolitan Open Land.pdf (A732) 8 - 9 6 A733 Exhibit 5 dragonflies.pdf (A733) 10 - 15 7 A734 Exhibit 6 quality of water.pdf (A734) 16 8 A735 Exhibit 7 Customer activities.pdf (A735) 17 9 A736 Exhibit 8 pylons.pdf (A736) 18 - 24 10 A737 Exhibit 9 Species-List.pdf (A737) 25 - 84 11 A738 Exhibit 10 magic maps.pdf (A738) 85 - 86 12 A739 Exhibit 11 Leisure and tourism Destination.pdf (A739) 87 13 A740 Exhibit 12 continuity through time.pdf (A740) 88 - 91 14 A741 Exhibit 13 The Plans for Denham Country Park.pdf (A741) 92 - 93 15 A742 Exhibit 14 Enabling Works.pdf (A742) 94 - 95 16 A743 Exhibit 15 Water Framework Directive.pdf (A743) 96 - 97 17 A744 Exhibit 16 Ecological_baseline_data_Mammals.pdf (A744) 98 - 108 18 A745 Exhibit 17 Wetlands_Programmes of measures_170907.pdf (A745) 109 - 117 19 A746 Exhibit 18 Guidance_protection animal species.pdf (A746) 118 - 136 20 A747 Exhibit 19 ODPM Circular 06_2005.pdf (A747) 137 - 151 HOL/00521/0001 EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 2 of 163 No Exhibit -

The Classification of Early Land Plants-Revisited*

The classification of early land plants-revisited* Harlan P. Banks Banks HP 1992. The c1assificalion of early land plams-revisiled. Palaeohotanist 41 36·50 Three suprageneric calegories applied 10 early land plams-Rhyniophylina, Zoslerophyllophytina, Trimerophytina-proposed by Banks in 1968 are reviewed and found 10 have slill some usefulness. Addilions 10 each are noted, some delelions are made, and some early planls lhal display fealures of more lhan one calegory are Sel aside as Aberram Genera. Key-words-Early land-plams, Rhyniophytina, Zoslerophyllophytina, Trimerophytina, Evolulion. of Plant Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York-5908, U.S.A. 14853. Harlan P Banks, Section ~ ~ ~ <ltm ~ ~-~unR ~ qro ~ ~ ~ f~ 4~1~"llc"'111 ~-'J~f.f3il,!"~, 'i\'1f~()~~<1I'f'I~tl'1l ~ ~1~il~lqo;l~tl'1l, 1968 if ~ -mr lfim;j; <fr'f ~<nftm~~Fmr~%1 ~~ifmm~~-.mtl ~if-.t~m~fuit ciit'!'f.<nftmciit~%1 ~ ~ ~ -.m t ,P1T ~ ~~ lfiu ~ ~ -.t 3!ftrq; ~ ;j; <mol ~ <Rir t ;j; w -.m tl FIRST, may I express my gratitude to the Sahni, to survey briefly the fate of that Palaeobotanical Sociery for the honour it has done reclassification. Several caveats are necessary. I recall me in awarding its International Medal for 1988-89. discussing an intractable problem with the late great May I offer the Sociery sincere thanks for their James M. Schopf. His advice could help many consideration. aspiring young workers-"Survey what you have and Secondly, may I join in celebrating the work and write up that which you understand. The rest will the influence of Professor Birbal Sahni. The one time gradually fall into line." That is precisely what I did I met him was at a meeting where he was displaying in 1968. -

New Lithuanian Records of Moths Captured in Beetle Traps

EKOLOGIJA. 2010. Vol. 56. No. 3–4. P. 105–109 DOI: 10.2478/v10055-010-0015-7 © Lietuvos mokslų akademija, 2010 © Lietuvos mokslų akademijos leidykla, 2010 New Lithuanian records of moths captured in beetle traps Henrikas Ostrauskas1, 2*, Moths were captured in multiple funnel traps used to survey xylophagous beetles in nine localities of Lithuania in 2002–2004. A total of 176 moths were caught, representing Povilas Ivinskis2 117 species. Loxostege virescalis (Guenée 1854) was collected at e tokai and is a new record for the Lithuanian fauna. Two very rare Lithuanian moth species, Ochsenheimeria vacculel- 1 State Service of Plant-growing, la Fisher von Röslerstamm 1842 and Spargania luctuata (Denis, Schiff ermüller, 1775), were under the Ministry of Agriculture, trapped at two and one new localities, respectively. In addition, new distribution records Ozo 4A, LT-08200 Vilnius, Lithuania are presented for 10 moth species that are considered to be rare in Lithuania. 2 Nature Research Centre, Key words: traps, Lepidoptera, species distribution, Lithuania Akademijos 2, LT-08412 Vilnius, Lithuania INTRODUCTION tre, Lithuania, Table 1) to maximise beetle trap catch. A sur- vey for xylophagous beetles was conducted in nine localities Th e last catalogue of Lithuanian moths was issued six years (Figure). During 2002, one attractant-baited trap per locality ago, and it comprised 2 455 species found in Lithuania (Ivins- was installed. In 2003–2004, the attractant-baited traps were kis, 2004). Moth fauna in Lithuania was studied thoroughly, supplemented with an additional control trap (no attractant) but the following investigations (Kazlauskas, 2006b; Kaz- in each locality. Th e traps were placed 1.5 m above the ground lauskas, Šlėnys, 2007; Paukštė, 2009) provided new impor- on stakes adjacent to stored timber or in truck control posts tant results. -

Desktop Biodiversity Report

Desktop Biodiversity Report Lindfield Rural and Urban Parishes ESD/14/65 Prepared for Terry Oliver 10th February 2014 This report is not to be passed on to third parties without prior permission of the Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre. Please be aware that printing maps from this report requires an appropriate OS licence. Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre report regarding land at Lindfield Rural and Urban Parishes 10/02/2014 Prepared for Terry Oliver ESD/14/65 The following information is enclosed within this report: Maps Sussex Protected Species Register Sussex Bat Inventory Sussex Bird Inventory UK BAP Species Inventory Sussex Rare Species Inventory Sussex Invasive Alien Species Full Species List Environmental Survey Directory SNCI L61 - Waspbourne Wood; M08 - Costells, Henfield & Nashgill Woods; M10 - Scaynes Hill Common; M18 - Walstead Cemetery; M25 - Scrase Valley Local Nature Reserve; M49 - Wickham Woods. SSSI Chailey Common. Other Designations/Ownership Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty; Environmental Stewardship Agreement; Local Nature Reserve; Notable Road Verge; Woodland Trust Site. Habitats Ancient tree; Ancient woodland; Coastal and floodplain grazing marsh; Ghyll woodland; Traditional orchard. Important information regarding this report It must not be assumed that this report contains the definitive species information for the site concerned. The species data held by the Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre (SxBRC) is collated from the biological recording community in Sussex. However, there are many areas of Sussex where the records held are limited, either spatially or taxonomically. A desktop biodiversity report from the SxBRC will give the user a clear indication of what biological recording has taken place within the area of their enquiry. -

Zootaxa, Catalogue of Family-Group Names in Cerambycidae

Zootaxa 2321: 1–80 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) ZOOTAXA 2321 Catalogue of family-group names in Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) YVES BOUSQUET1, DANIEL J. HEFFERN2, PATRICE BOUCHARD1 & EUGENIO H. NEARNS3 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Central Experimental Farm, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 10531 Goldfield Lane, Houston, TX 77064, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Biology, Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Corresponding author: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by Q. Wang: 2 Dec. 2009; published: 22 Dec. 2009 Yves Bousquet, Daniel J. Heffern, Patrice Bouchard & Eugenio H. Nearns CATALOGUE OF FAMILY-GROUP NAMES IN CERAMBYCIDAE (COLEOPTERA) (Zootaxa 2321) 80 pp.; 30 cm. 22 Dec. 2009 ISBN 978-1-86977-449-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-450-9 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2009 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2009 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. -

An Alternative Model for the Earliest Evolution of Vascular Plants

1 1 An alternative model for the earliest evolution of vascular plants 2 3 BORJA CASCALES-MINANA, PHILIPPE STEEMANS, THOMAS SERVAIS, KEVIN LEPOT 4 AND PHILIPPE GERRIENNE 5 6 Land plants comprise the bryophytes and the polysporangiophytes. All extant polysporangiophytes are 7 vascular plants (tracheophytes), but to date, some basalmost polysporangiophytes (also called 8 protracheophytes) are considered non-vascular. Protracheophytes include the Horneophytopsida and 9 Aglaophyton/Teruelia. They are most generally considered phylogenetically intermediate between 10 bryophytes and vascular plants, and are therefore essential to elucidate the origins of current vascular 11 floras. Here, we propose an alternative evolutionary framework for the earliest tracheophytes. The 12 supporting evidence comes from the study of the Rhynie chert historical slides from the Natural History 13 Museum of Lille (France). From this, we emphasize that Horneophyton has a particular type of tracheid 14 characterized by narrow, irregular, annular and/or, possibly spiral wall thickenings of putative secondary 15 origin, and hence that it cannot be considered non-vascular anymore. Accordingly, our phylogenetic 16 analysis resolves Horneophyton and allies (i.e., Horneophytopsida) within tracheophytes, but as sister 17 to eutracheophytes (i.e., extant vascular plants). Together, horneophytes and eutracheophytes form a 18 new clade called herein supereutracheophytes. The thin, irregular, annular to helical thickenings of 19 Horneophyton clearly point to a sequential acquisition of the characters of water-conducting cells. 20 Because of their simple conducting cells and morphology, the horneophytophytes may be seen as the 21 precursors of all extant vascular plant biodiversity. 22 23 Keywords: Rhynie chert, Horneophyton, Tracheophyte, Lower Devonian, Cladistics. -

Moths and Management of a Grassland Reserve: Regular Mowing and Temporary Abandonment Support Different Species

Biologia 67/5: 973—987, 2012 Section Zoology DOI: 10.2478/s11756-012-0095-9 Moths and management of a grassland reserve: regular mowing and temporary abandonment support different species Jan Šumpich1,2 &MartinKonvička1,3* 1Biological Centre CAS, Institute of Entomology, Branišovská 31,CZ-37005 České Budějovice, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected] 2Česká Bělá 212,CZ-58261 Česká Bělá, Czech Republic 3Faculty of Sciences, University South Bohemia, Branišovská 31,CZ-37005 České Budějovice, Czech Republic Abstract: Although reserves of temperate seminatural grassland require management interventions to prevent succesional change, each intervention affects the populations of sensitive organisms, including insects. Therefore, it appears as a wise bet-hedging strategy to manage reserves in diverse and patchy manners. Using portable light traps, we surveyed the effects of two contrasting management options, mowing and temporary abandonment, applied in a humid grassland reserve in a submountain area of the Czech Republic. Besides of Macrolepidoptera, we also surveyed Microlepidoptera, small moths rarely considered in community studies. Numbers of individiuals and species were similar in the two treatments, but ordionation analyses showed that catches originating from these two treatments differed in species composition, management alone explaining ca 30 per cent of variation both for all moths and if split to Marcolepidoptera and Microlepidoptera. Whereas a majority of macrolepidopteran humid grassland specialists preferred unmown sections or displayed no association with management, microlepidopteran humid grassland specialists contained equal representation of species inclining towards mown and unmown sections. We thus revealed that even mown section may host valuable species; an observation which would not have been detected had we considered Macrolepidoptera only.