Jesuits and Social Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards a Symposium

One Hundred Years of Thomism Aeterni Patris and Afterwards A Symposium Edited By Victor B. Brezik, C.S.B, CENTER FOR THOMISTIC STUDIES University of St. Thomas Houston, Texas 77006 ~ NIHIL OBSTAT: ReverendJamesK. Contents Farge, C.S.B. Censor Deputatus INTRODUCTION . 1 IMPRIMATUR: LOOKING AT THE PAST . 5 Most Reverend John L. Morkovsky, S.T.D. A Remembrance Of Pope Leo XIII: The Encyclical Aeterni Patris, Leonard E. Boyle,O.P. 7 Bishop of Galveston-Houston Commentary, James A. Weisheipl, O.P. ..23 January 6, 1981 The Legacy Of Etienne Gilson, Armand A. Maurer,C.S.B . .28 The Legacy Of Jacques Maritain, Christian Philosopher, First Printing: April 1981 Donald A. Gallagher. .45 LOOKING AT THE PRESENT. .61 Copyright©1981 by The Center For Thomistic Studies Reflections On Christian Philosophy, All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or Ralph McInerny . .63 reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written Thomism And Today's Crisis In Moral Values, Michael permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in Bertram Crowe . .74 critical articles and reviews. For information, write to The Transcendental Thomism, A Critical Assessment, Center For Thomistic Studies, 3812 Montrose Boulevard, Robert J. Henle, S.J. 90 Houston, Texas 77006. LOOKING AT THE FUTURE. .117 Library of Congress catalog card number: 80-70377 Can St. Thomas Speak To The Modem World?, Leo Sweeney, S.J. .119 The Future Of Thomistic Metaphysics, ISBN 0-9605456-0-3 Joseph Owens, C.Ss.R. .142 EPILOGUE. .163 The New Center And The Intellectualism Of St. Thomas, Printed in the United States of America Vernon J. -

New Books for December 2019 Grace, Predestination, and the Permission of Sin: a Thomistic Analysis by O'neill, Taylor Patrick, A

New Books for December 2019 Grace, predestination, and the permission of sin: a Thomistic analysis by O'Neill, Taylor Patrick, author. Book B765.T54 O56 2019 Faith and the founders of the American republic Book BL2525 .F325 2014 Moral combat: how sex divided American Christians and fractured American politics by Griffith, R. Marie 1967- author. (Ruth Marie), Book BR516 .G75 2017 Southern religion and Christian diversity in the twentieth century by Flynt, Wayne, 1940- author. Book BR535 .F59 2016 The story of Latino Protestants in the United States by Martínez, Juan Francisco, 1957- author. Book BR563.H57 M362 2018 The land of Israel in the Book of Ezekiel by Pikor, Wojciech, Book BS1199.L28 P55 2018 2 Kings by Park, Song-Mi Suzie, author. Book BS1335.53 .P37 2019 The Parables in Q by Roth, Dieter T., author. Book BS2555.52 .R68 2018 Hearing Revelation 1-3: listening with Greek rhetoric and culture by Neyrey, Jerome H., 1940- author. Book BS2825.52 .N495 2019 "Your God is a devouring fire": fire as a motif of divine presence and agency in the Hebrew Bible by Simone, Michael R., 1972- author. Book BS680.F53 S56 2019 Trinitarian and cosmotheandric vision by Panikkar, Raimon, Book BT111.3 .P36 2019 The life of Jesus: a graphic novel by Alex, Ben, author. Book BT302 .M66 2017 Our Lady of Guadalupe: the graphic novel by Muglia, Natalie, Book BT660.G8 M84 2018 An ecological theology of liberation: salvation and political ecology by Castillo, Daniel Patrick, author. Book BT83.57 .C365 2019 The Satan: how God's executioner became the enemy by Stokes, Ryan E., Book BT982 .S76 2019 Lectio Divina of the Gospels: for the liturgical year 2019-2020. -

The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 56 Number 1 Article 5 The Pre-History of Subsidiarity in Leo XIII Michael P. Moreland Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FINAL_MORELAND 8/14/2018 9:10 PM THE PRE-HISTORY OF SUBSIDIARITY IN LEO XIII MICHAEL P. MORELAND† Christian Legal Thought is a much-anticipated contribution from Patrick Brennan and William Brewbaker that brings the resources of the Christian intellectual tradition to bear on law and legal education. Among its many strengths, the book deftly combines Catholic and Protestant contributions and scholarly material with more widely accessible sources such as sermons and newspaper columns. But no project aiming at a crisp and manageably-sized presentation of Christianity’s contribution to law could hope to offer a comprehensive treatment of particular themes. And so, in this brief essay, I seek to elaborate upon the treatment of the principle of subsidiarity in Catholic social thought. Subsidiarity is mentioned a handful of times in Christian Legal Thought, most squarely with a lengthy quotation from Pius XI’s articulation of the principle in Quadragesimo Anno.1 In this proposed elaboration of subsidiarity, I wish to broaden the discussion of subsidiarity historically (back a few decades from Quadragesimo Anno to the pontificate of Leo XIII) and philosophically (most especially its relation to Leo XIII’s revival of Thomism).2 Statements of the principle have historically been terse and straightforward even if the application of subsidiarity to particular legal questions has not. -

Gen Assembly Report Extended V1

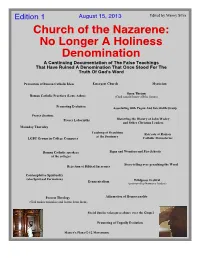

Edition 1 August 15, 2013 Edited by Manny Silva Church of the Nazarene: No Longer A Holiness Denomination A Continuing Documentation of The False Teachings That Have Ruined A Denomination That Once Stood For The Truth Of God's Word Promotion of Roman Catholic Ideas Emergent Church Mysticism Open Theism Roman Catholic Practices (Lent, Ashes) (God cannot know all the future) Promoting Evolution Associating with Pagan And Interfaith Group Prayer Stations Prayer Labyrinths Distorting the History of John Wesley and Other Christian Leaders Maunday Thursday Teaching of Occultism Retreats at Roman at the Seminary LGBT Groups in College Campuses Catholic Monasteries Roman Catholic speakers Signs and Wonders and Fire Schools at the colleges Story-telling over preaching the Word Rejection of Biblical Inerrancy Contemplative Spirituality (aka Spiritual Formation) Ecumenicalism Wildgoose Festival (promoted by Nazarene leaders) Process Theology Affirmation of Homosexuality (God makes mistakes and learns from them) Social Justice takes precedence over the Gospel Promoting of Ungodly Evolution Master's Plan (G-12 Movement) The Church of the Nazarene: General Assembly 2013 Report, And Various Papers Documenting The Heresies In The Church [This document can be copied and distributed to others to alert them to the state of the Church of the Nazarene and its universities and colleges. This document has been compiled for the sake of the brothers and sisters in Christ in the Church of the Nazarene. It is solely driven by love for those who may be, or have been, deceived by the many false teachings and teachers that have invaded the church. I cannot explain exactly why such blatantly unbiblical and satanic teachings have fooled so many. -

The Anderson Report: Sexual Abuse in The

FPO The Anderson Report Sexual Abuse in the Diocese of Phoenix AndersonAdvocates.com • 602.682.2810 “For many of us, those earlier stories happened someplace else, someplace away. Now we know the truth: it happened everywhere.” ~ Pennsylvania Grand Jury Report 2018 Table of Contents Purpose & Background ...........................................................................................6 Abuse in the Diocese of Phoenix ................................................................................ 8 History of the Diocese of Phoenix .............................................................................. 8 Bishop O’Brien Agreement with Maricopa County Attorney’s Office ..................... 9 Lists of Priests Accused of Sexual Abuse in the Diocese of Phoenix: Priests and Deacons from the Diocese of Phoenix Who Have been Accused of Sexual Misconduct with a Minor and Have a Canonical Case in Process ............................................................................................................... 18 Priests and Deacons Who Have Been Laicized and/or Removed from Ministry Due to Sexual Misconduct with a Minor ..................................... 19 Priests and Deacons from Other Dioceses who May No Longer Serve in the Diocese of Phoenix Due to Sexual Misconduct with a Minor ..................... 20 Priests Who Have Served in the Diocese of Phoenix Who Have Been Laicized and/or Removed from Ministry by Their Communities Due to Sexual Misconduct with a Minor .................................................................... -

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China

Life, Thought and Image of Wang Zheng, a Confucian-Christian in Late Ming China Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Ruizhong Ding aus Qishan, VR. China Bonn, 2019 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Dr. Manfred Hutter, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kubin, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Betreuer und Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Ralph Kauz, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Veronika Veit, Institut für Orient- und Asienwissenschaften (weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung:22.07.2019 Acknowledgements Currently, when this dissertation is finished, I look out of the window with joyfulness and I would like to express many words to all of you who helped me. Prof. Wolfgang Kubin accepted me as his Ph.D student and in these years he warmly helped me a lot, not only with my research but also with my life. In every meeting, I am impressed by his personality and erudition deeply. I remember one time in his seminar he pointed out my minor errors in the speech paper frankly and patiently. I am indulged in his beautiful German and brilliant poetry. His translations are full of insightful wisdom. Every time when I meet him, I hope it is a long time. I am so grateful that Prof. Ralph Kauz in the past years gave me unlimited help. In his seminars, his academic methods and sights opened my horizons. Usually, he supported and encouraged me to study more fields of research. -

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES to MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences Of

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Matthew Glen Minix UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2016 MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew G. APPROVED BY: _____________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader. _____________________________________ Anthony Burke Smith, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ John A. Inglis, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ Jack J. Bauer, Ph.D. _____________________________________ Daniel Speed Thompson, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Religious Studies ii © Copyright by Matthew Glen Minix All rights reserved 2016 iii ABSTRACT MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew Glen University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation considers a spectrum of five distinct approaches that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomist Catholic thinkers utilized when engaging with the tradition of modern scientific psychology: a critical approach, a reformulation approach, a synthetic approach, a particular [Jungian] approach, and a personalist approach. This work argues that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomists were essentially united in their concerns about the metaphysical principles of many modern psychologists as well as in their worries that these same modern psychologists had a tendency to overlook the transcendent dimension of human existence. This work shows that the first four neo-Thomist thinkers failed to bring the traditions of neo-Thomism and modern psychology together to the extent that they suggested purely theoretical ways of reconciling them. -

Download Article PDF , Format and Size of the File

History of humanitarian ideas The historical foundations of humanitarian action by Dr. Jean Guillermand After nearly 130 years of existence, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement continues to play a unique and important role in the field of human relations. Its origin may be traced to the impression made on Henry Dunant, a chance witness at the scene, by the disastrous lack of medical care at the battle of Solferino in 1859 and the compassionate response aroused in the people of Lombardy by the plight of the wounded. The Movement has since gained importance and expanded to such a degree that it is now an irreplaceable institution made up of dedicated people all over the world. The Movement's success can clearly be attributed in great part to the commitment of those who carried on the pioneering work of its founders. But it is also the result of a constantly growing awareness of the conditions needed for such work to be accomplished. The initial text of the 1864 Convention was already quite explicit about its application in situations of armed conflict. Jean Pictet's analysis in 19S5 and the adoption by the Vienna Conference of the seven Fundamental Principles in 1965 have since codified in international law what was originally a generous and spontaneous impulse. In a world where the weight of hard-hitting arguments and the impact of the media play a key role in shaping public opinion, the fact that the Movement's initial spirit has survived intact and strong without having recourse to aggressive publicity campaigns or losing its independence to the political ideologies that divide the globe may well surprise an impartial observer of society today. -

The Holy See, Social Justice, and International Trade Law: Assessing the Social Mission of the Catholic Church in the Gatt-Wto System

THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT-WTO SYSTEM By Copyright 2014 Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma Submitted to the graduate degree program in Law and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D) ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) _______________________________ Professor Virginia Harper Ho (Member) ________________________________ Professor Uma Outka (Member) ________________________________ Richard Coll (Member) Date Defended: May 15, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HOLY SEE, SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW: ASSESSING THE SOCIAL MISSION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN THE GATT- WTO SYSTEM by Fr. Alphonsus Ihuoma ________________________________ Professor Raj Bhala (Chairperson) Date approved: May 15, 2014 ii ABSTRACT Man, as a person, is superior to the state, and consequently the good of the person transcends the good of the state. The philosopher Jacques Maritain developed his political philosophy thoroughly informed by his deep Catholic faith. His philosophy places the human person at the center of every action. In developing his political thought, he enumerates two principal tasks of the state as (1) to establish and preserve order, and as such, guarantee justice, and (2) to promote the common good. The state has such duties to the people because it receives its authority from the people. The people possess natural, God-given right of self-government, the exercise of which they voluntarily invest in the state. -

Sharing the Passion for Research Brain Gain: Neurosurgery Study Spring 2008 View the Magazine Online At: SPRING 2008 University Magazine

Sharing the Passion for Research Brain Gain: Neurosurgery Study Spring 2008 View the magazine online at: SPRING 2008 www.creightonmagazine.org University Magazine Called to Teach ................................................................10 With some Catholic elementary and high schools struggling to attract and retain high- quality teachers, Creighton University’s Magis program offers a possible solution. Program participants work toward a master’s degree in education, tuition-free, while serving in Catholic schools — especially those struggling economically. These Magis teachers also engage in spiritual formation and live together in community, rounding out their education. Sharing the Passion for Research ...............................16 Creighton University students, including undergraduates, are often extended unique opportunities to collaborate with faculty members who have distinguished themselves as 10 leading scholars in their fields. Creighton’s Bridget Keegan, Ph.D., shares a few of these stories. Brain Gain .......................................................................22 A second-year medical student works with two Creighton researchers in a breakthrough study that finds that oxygenating the brain during neurosurgery not only reduces mortality, but enhances overall patient outcomes. Their research drew the attention of the prestigious American Association of Neurological Surgeons. 16 On the cover: Clockwise from upper left, Creighton University Magis teacher John Roselle, BA’07; the Most Rev. Elden Curtiss, archbishop of Omaha, congratulating the Magis teachers at a special “missioning Mass”; Magis teacher Jeff Dorr teaching at the Red Cloud Indian School; Magis teacher Jennifer Ward working with students at St. Richard School in Omaha; and two students at Red Cloud. 22 University News .....................4 Correction: Isabelle Cherney, BA’96, Ph.D., was incorrectly listed as the director Campaign News ..................26 of Creighton’s honors program in the Winter 2007 issue. -

Promotio Iustitiae No

Nº 117, 2015/1 Promotio Iustitiae Martyrs for justice From Latin America Juan Hernández Pico, SJ Aloir Pacini, SJ From Africa David Harold-Barry, SJ Jean Baptiste Ganza, SJ From South Asia William Robins, SJ M.K. Jose, SJ From Asia Pacific Juzito Rebelo, SJ Social Justice and Ecology Secretariat Social Justice and Ecology Secretariat Society of Jesus Editor: Patxi Álvarez sj Publishing Coordinator: Concetta Negri Promotio Iustitiae is published by the Social Justice Secretariat at the General Curia of the Society of Jesus (Rome) in English, French, Italian and Spanish. Promotio Iustitiae is available electronically on the World Wide Web at the following address: www.sjweb.info/sjs If you are struck by an idea in this issue, your brief comment is very welcome. To send a letter to Promotio Iustitiae for inclusion in a future issue, please write to the fax or email address shown on the back cover. The re-printing of the document is encouraged; please cite Promotio Iustitiae as the source, along with the address, and send a copy of the re-print to the Editor. 2 Social Justice and Ecology Secretariat Contents Editorial .................................................................................. 4 Patxi Álvarez, SJ The legacy of the martyrs of El Salvador ..................................... 6 Juan Hernández Pico, SJ With martyrdom is reborn the hope of the indigenous peoples of Mato Grosso .......................................................................... 10 Aloir Pacini, SJ The seven Jesuit martyrs of Zimbabwe...................................... 14 David Harold-Barry, SJ Three grains planted in the Rwandan soil .................................. 18 Jean Baptiste Ganza, SJ A Haven for the Homeless: Fr. Thomas E. Gafney, SJ .................. 21 William Robins, SJ Fr. -

The Anderson Report: Sexual Abuse in the Diocese of Albany

The Anderson Report Sexual Abuse in the Diocese of Albany AndersonAdvocates.com • 646.759.2551 “For many of us, those earlier stories happened someplace else, someplace away. Now we know the truth: it happened everywhere.” ~ Pennsylvania Grand Jury Report 2018 Table of Contents Purpose & Background ...........................................................................................7 Sexual Abuse in the Diocese of Albany ................................................................10 Those Accused of Sexual Misconduct in the Diocese of Albany ............................ 11 AndersonAdvocates.com 3 Attorney Advertising Those Accused of Sexual Abuse in the Diocese of Albany Adams, Anthony ...........................................12 Hanney, James Vincent (Vincent J. Hanney, Bell, Francis ..................................................12 James A. Hanney, James Hanney) ................24 Bentley, David G. ..........................................12 Heim, William J. ...........................................24 Bertolucci, John Patrick ...............................13 Jones, Richard ...............................................24 Bolton, Donald ..............................................13 Jupin, Alan D. ...............................................25 Boucher, Anthony ........................................14 Kelly, James E. ..............................................25 Cahill, William B. .........................................14 Keyrouze, Joseph ..........................................25 Callaghan, George J. .....................................14