Consequences of Hatchery Stocking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT LUCKENBACH, JOHN ADAM. Breeding Biotechnology

ABSTRACT LUCKENBACH, JOHN ADAM. Breeding Biotechnology, Sex Determination, and Growth in Southern flounder, Paralichthys lethostigma. (Under the direction of Dr. John Godwin and Dr. Russell J. Borski). Southern flounder (Paralichthys lethostigma) support valuable, but declining US fisheries. This species is therefore a strong candidate for aquaculture to mitigate fishing impacts and stabilize seafood supply. Because female flounder reach substantially larger sizes than males, all-female culture is desirable for commercial aquaculture. Hence, a thorough understanding of sexual development, its timing and regulation by temperature is essential for optimization of flounder aquaculture. To better understand ovarian and testicular development in southern flounder, structural and cellular sex-distinguishing markers were studied using histological methods. We found that histologically discernible sex differentiation occurs in southern flounder at ~75-120 mm TL and that early differentiation is considerably delayed relative to its Japanese congener, P. olivaceus. High (28°C) and low (18°C) water temperatures, produced a higher proportion of males (96% and 78% males, respectively). The sex ratio at a mid-range (23°C) temperature was not different from 1:1. This suggests that southern flounder possess a temperature sensitive mechanism of sex determination. Growth was also affected by temperature with the temperature that maximized females inducing better growth. Aromatase cytochrome P450 (P450arom) is responsible for estrogen biosynthesis and plays a critical role in ovarian differentiation. We cloned ovarian P450arom and developed a qRT-PCR for assessment of early sex differentiation. The deduced amino acid sequence for southern flounder P450arom is very similar to P450arom in other teleosts. Comparison of P450arom intron sequences of southern flounder within and between different populations revealed substantial inter-individual variation that may affect sex determination responses. -

Schedule Onlinepdf

Detailed schedule 8:30 Opening session 9:00 Keynote lecture: Impacts of climate change on flatfish populations - patterns of change 100 days to 100 years: Short and long-term responses of flatfish to sea temperature change David Sims 9:30 Nine decades of North Sea sole and plaice distributions Georg H. Engelhard (Engelhard GH, Pinnegar JK, Kell LT, Rijnsdorp AD) 9:50 Climatic effects on recruitment variability in Platichthys flesus and Solea solea: defining perspectives for management. Filipe Martinho (Martinho F, Viegas I, Dolbeth M, Sousa H, Cabral HN, Pardal MA) 10:10 Are flatfish species with southern biogeographic affinities increasing in the Celtic Sea? Christopher Lynam (Lynam C, Harlay X, Gerritsen H, Stokes D) 10:30 Coffee break 11:00 Climate related changes in abundance of non-commercial flatfish species in the North Sea Ralf van Hal (van Hal R, Smits K, Rijnsdorp AD) 11:20 Inter-annual variability of potential spawning habitat of North Sea plaice Christophe Loots (Loots C, Vaz S, Koubii P, Planque B, Coppin F, Verin Y) 11:40 Annual variation in simulated drift patterns of egg/larvae from spawning areas to nursery and its implication for the abundance of age-0 turbot (Psetta maxima) Claus R. Sparrevohn (Sparrevohn CR, Hinrichsen H-H, Rijnsdorp AD) 12:00 Broadscale patterns in population dynamics of juvenile plaice: W Scotland 2001-2008 Michael T. Burrows (Burrows MT, Robb L, Harvey R, Batty RS) 12:20 Impact of global warming on abundance and occurrence of flatfish populations in the Bay of Biscay (France) Olivier Le Pape (Hermant -

Session Summaries-2008

Session Summaries-2008 SUMMARY OF SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS AND WORKSHOPS Science Board Symposium (S1) Beyond observations to achieving understanding and forecasting in a changing North Pacific: Forward to the FUTURE Co-Convenors: John E. Stein (SB), Michael J. Dagg (BIO), Gordon H. Kruse (FIS), Glen S. Jamieson (MEQ), Hiroya Sugisaki (MONITOR), Michael G. Foreman (POC), Bernard A. Megrey (TCODE), Harold P. Batchelder (CCCC), Michio J. Kishi (CCCC), Fangli Qiao (China), Sinjae Yoo (Korea) and Mikhail Stepanenko (Russia) Background FUTURE (Forecasting and Understanding Trends, Uncertainty and Responses of North Pacific Marine Ecosystems), the new Science Program undertaken by PICES member countries, has the broad goals of: (1) understanding the responses of marine ecosystems in the North Pacific to climate change and human activities at basin-wide and regional scales; (2) providing forecasts of what might be expected based on a current understanding of how nature works; and (3) communicating this information effectively to its members and to society in general. Past advances in understanding marine ecosystems in the North Pacific have been largely based either on the direct analysis of observations, or on the development of conceptual and numerical models that help to describe the processes underlying the observations. Though these activities will continue to play an important role in FUTURE, the provision of forecasts and estimates of their associated uncertainties necessitates moving beyond observationally based understanding, so that ecosystem responses to natural and anthropogenic changes can be anticipated and communicated effectively to society. Presentations were invited to address the goals of FUTURE and the three key research questions that it identifies: 1. -

Shellfish Diseases and Their Management in Commercial Recirculating Systems

Shellfish Diseases and Their Management in Commercial Recirculating Systems Ralph Elston AquaTechnics & Pacific Shellfish Institute PO Box 687 Carlsborg, WA 98324 Introduction Intensive culture of early life stages of bivalve shellfish culture has been practiced since at least the late 1950’s on an experimental basis. Production scale culture emerged in the 1970’s and today, hathcheries and nurseries produce large numbers of a variety of species of oysters, clams and scallops. The early life stage systems may be entirely or partially recirculating or static. Management of infectious diseases in these systems has been a challenge since their inception and effective health management is a requisite to successful culture. The diseases which affect early life stage shellfish in intensive production systems and the principles and practice of health management are the subject of this presentation. Shellfish Diseases and Management Diseases of bivalve shellfish affecting those reared or harvested from extensive culture primarily consist of parasitic infections and generally comprise the reportable or certifiable diseases. Due to the extensive nature of such culture, intervention options or disease control are limited. In contrast, infectious diseases known from early life stages in intensive culture systems tend to be opportunistic in nature and offer substantial opportunity for management due to the control that can be exerted at key points in the systems. In marine shellfish hatcheries, infectious organisms can enter the system from three sources: brood stock, seawater source and algal food source. Once an organism is established in the system, it may persist without further introduction. Bacterial infections are the most common opportunistic infection in shellfish hatcheries. -

2018 Final LOFF W/ Ref and Detailed Info

Final List of Foreign Fisheries Rationale for Classification ** (Presence of mortality or injury (P/A), Co- Occurrence (C/O), Company (if Source of Marine Mammal Analogous Gear Fishery/Gear Number of aquaculture or Product (for Interactions (by group Marine Mammal (A/G), No RFMO or Legal Target Species or Product Type Vessels processor) processing) Area of Operation or species) Bycatch Estimates Information (N/I)) Protection Measures References Detailed Information Antigua and Barbuda Exempt Fisheries http://www.fao.org/fi/oldsite/FCP/en/ATG/body.htm http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/y5402e/y5402e06.htm,ht tp://www.tradeboss.com/default.cgi/action/viewcompan lobster, rock, spiny, demersal fish ies/searchterm/spiny+lobster/searchtermcondition/1/ , (snappers, groupers, grunts, ftp://ftp.fao.org/fi/DOCUMENT/IPOAS/national/Antigua U.S. LoF Caribbean spiny lobster trap/ pot >197 None documented, surgeonfish), flounder pots, traps 74 Lewis Fishing not applicable Antigua & Barbuda EEZ none documented none documented A/G AndBarbuda/NPOA_IUU.pdf Caribbean mixed species trap/pot are category III http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/interactions/fisheries/tabl lobster, rock, spiny free diving, loops 19 Lewis Fishing not applicable Antigua & Barbuda EEZ none documented none documented A/G e2/Atlantic_GOM_Caribbean_shellfish.html Queen conch (Strombus gigas), Dive (SCUBA & free molluscs diving) 25 not applicable not applicable Antigua & Barbuda EEZ none documented none documented A/G U.S. trade data Southeastern U.S. Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico, and Caribbean snapper- handline, hook and grouper and other reef fish bottom longline/hook-and-line/ >5,000 snapper line 71 Lewis Fishing not applicable Antigua & Barbuda EEZ none documented none documented N/I, A/G U.S. -

Betanodavirus and VER Disease: a 30-Year Research Review

pathogens Review Betanodavirus and VER Disease: A 30-year Research Review Isabel Bandín * and Sandra Souto Departamento de Microbioloxía e Parasitoloxía-Instituto de Acuicultura, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 December 2019; Accepted: 4 February 2020; Published: 9 February 2020 Abstract: The outbreaks of viral encephalopathy and retinopathy (VER), caused by nervous necrosis virus (NNV), represent one of the main infectious threats for marine aquaculture worldwide. Since the first description of the disease at the end of the 1980s, a considerable amount of research has gone into understanding the mechanisms involved in fish infection, developing reliable diagnostic methods, and control measures, and several comprehensive reviews have been published to date. This review focuses on host–virus interaction and epidemiological aspects, comprising viral distribution and transmission as well as the continuously increasing host range (177 susceptible marine species and epizootic outbreaks reported in 62 of them), with special emphasis on genotypes and the effect of global warming on NNV infection, but also including the latest findings in the NNV life cycle and virulence as well as diagnostic methods and VER disease control. Keywords: nervous necrosis virus (NNV); viral encephalopathy and retinopathy (VER); virus–host interaction; epizootiology; diagnostics; control 1. Introduction Nervous necrosis virus (NNV) is the causative agent of viral encephalopathy and retinopathy (VER), otherwise known as viral nervous necrosis (VNN). The disease was first described at the end of the 1980s in Australia and in the Caribbean [1–3], and has since caused a great deal of mortalities and serious economic losses in a variety of reared marine fish species, but also in freshwater species worldwide. -

Proceedings of the 40Th U.S.-Japan Aquaculture Panel Symposium

Hatchery Technology for High Quality Juvenile Production Proceedings of the 40th U.S.-Japan Aquaculture Panel Symposium University of Hawaii East West Center Honolulu, Hawaii October 22-23 2012 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-F/SPO-136 Hatchery Technology for High Quality Juvenile Production Proceedings of the 40th U.S.-Japan Aquaculture Panel Symposium University of Hawaii East West Center Honolulu, Hawaii October 22-23 2012 Mike Rust1, Paul Olin2, April Bagwill3, and Marie Fujitani3, editors 1Northwest Fisheries Science Center 2725 Montlake Boulevard East Seattle, Washington 98112 2California Sea Grant UCSD / Scripps Institution of Oceanography 133 Aviation Blvd., Suite 109 Santa Rosa CA 95403 3NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service 1315 East-West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910 NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-F/SPO-136 December 2013 U.S. Department of Commerce Penny Pritzker, Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Dr. Kathryn Sullivan, (Acting) NOAA Administrator National Marine Fisheries Service Samuel D. Rauch III, (Acting) Assistant Administrator for Fisheries SUGGESTED CITATION: Rust, M., P. Olin, A. Bagwill and M. Fujitani (editors). 2013. Hatchery Technology for High Quality Juvenile Production: Proceedings of the 40th U.S.-Japan Aquaculture Panel Symposium, Honolulu, Hawaii, October 22-23, 2012. U.S. Dept. Commerce, NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-F/SPO-136. A COPY OF THIS REPORT MAY BE OBTAINED FROM: Northwest Fisheries Science Center 2725 Montlake Boulevard East Seattle, Washington 98112 OR ONLINE AT: http://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/tm/ Reference throughout this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. -

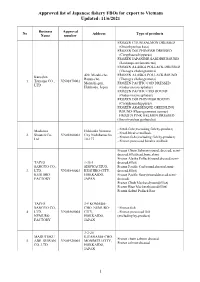

Approved List of Japanese Fishery Fbos for Export to Vietnam Updated: 11/6/2021

Approved list of Japanese fishery FBOs for export to Vietnam Updated: 11/6/2021 Business Approval No Address Type of products Name number FROZEN CHUM SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus keta) FROZEN DOLPHINFISH DRESSED (Coryphaena hippurus) FROZEN JAPANESE SARDINE ROUND (Sardinops melanostictus) FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK DRESSED (Theragra chalcogramma) 420, Misaki-cho, FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK ROUND Kaneshin Rausu-cho, (Theragra chalcogramma) 1. Tsuyama CO., VN01870001 Menashi-gun, FROZEN PACIFIC COD DRESSED LTD Hokkaido, Japan (Gadus macrocephalus) FROZEN PACIFIC COD ROUND (Gadus macrocephalus) FROZEN DOLPHIN FISH ROUND (Coryphaena hippurus) FROZEN ARABESQUE GREENLING ROUND (Pleurogrammus azonus) FROZEN PINK SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) - Fresh fish (excluding fish by-product) Maekawa Hokkaido Nemuro - Fresh bivalve mollusk. 2. Shouten Co., VN01860002 City Nishihamacho - Frozen fish (excluding fish by-product) Ltd 10-177 - Frozen processed bivalve mollusk Frozen Chum Salmon (round, dressed, semi- dressed,fillet,head,bone,skin) Frozen Alaska Pollack(round,dressed,semi- TAIYO 1-35-1 dressed,fillet) SANGYO CO., SHOWACHUO, Frozen Pacific Cod(round,dressed,semi- 3. LTD. VN01840003 KUSHIRO-CITY, dressed,fillet) KUSHIRO HOKKAIDO, Frozen Pacific Saury(round,dressed,semi- FACTORY JAPAN dressed) Frozen Chub Mackerel(round,fillet) Frozen Blue Mackerel(round,fillet) Frozen Salted Pollack Roe TAIYO 3-9 KOMABA- SANGYO CO., CHO, NEMURO- - Frozen fish 4. LTD. VN01860004 CITY, - Frozen processed fish NEMURO HOKKAIDO, (excluding by-product) FACTORY JAPAN -

Sex Ratio and Growth Performance of Gynogenetic Diploid Barfin Flounder Verasper Moseri

Aquaculture Sci. 59(3),375-382(2011) Sex Ratio and Growth Performance of Gynogenetic Diploid Barfin Flounder Verasper moseri 1,* 1 1 2 Tatsunari MORI , Setsuo SAITO , Taihei MATSUDA , Takaaki KAYABA , 3 3 3 Chiharu KISHIOKA , Zineb LAHRECH and Katsutoshi ARAI Abstract: The effects of rearing temperature and genetic factor on the sex ratio of normal and gynogenetic diploids were examined in barfin flounder Verasper moseri. In addition, growth perfor- mance at the age of 6 to 34 months after hatching was also examined. In 16℃ (16.1±0.14) group, the percentage of females in gynogenetic diploids (G1) and normal diploids (2N) was significantly lower than in 14℃ (13.6±0.33) and 12℃ (12.0±0.30) group. However, no clear difference was observed in the female rate between 14℃ and 12℃ group. These results indicated that rear- ing temperature affects the sex ratio of both G1 and 2N, and high temperature (16℃) condition induced male-biased sex ratios. Among gynogenetic strains, female rates widely varied from 7.0% to 95.1% in the 14℃ and 12℃ condition. However, several cases exhibited high female rates (89.5 to 95.1%), suggesting that this species essentially has the male heterogametic (XX female-XY male) sex determination system. At 34 months, body weight of G1 (1569.0±328.4 g) was sig- nificantly heavier than 2N (866.6±283.8 g). Survival rates of 2N and G1 from 6 to 34 months were 98.0% and 96.0%, respectively. These results indicate that the group with a high percentage of females showed better growth. -

Microsatellite Analysis As a Tool for Discriminating an Interfamily Hybrid Between Olive Flounder and Starry Flounder

Microsatellite analysis as a tool for discriminating an interfamily hybrid between olive flounder and starry flounder J.-H. Kang1, Y.-K. Kim1, J.-Y. Park1, C.-M. An1, M.-M. Nam2, S.G. Byun2, B.I. Lee2, J.H. Lee2 and T.-J. Choi3 1Biotechnology Research Division, Busan, Korea 2East Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Uljin, Korea 3Department of Microbiology, Pukyong National University, Busan, Korea Corresponding author: T.-J. Choi E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 10 (4): 2786-2794 (2011) Received May 30, 2011 Accepted September 7, 2011 Published October 31, 2011 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/2011.October.31.16 ABSTRACT. An interspecific artificial hybrid was produced between two economically important aquaculture flatfish: olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) and starry flounder (P. stellatus). This hybrid displays the rapid growth characteristic of the former and tolerance to low temperatures and low salinity of the latter, but the genetics of inheritance in this hybrid have not been elucidated. Polymorphic microsatellite markers developed for P. olivaceus and P. stellatus were tested to determine if these markers can be used for analysis of parentage and genetic inheritance. Multiplex PCR using two primer sets that were specific to each species produced PCR products of different sizes; these could be used for the identification of interspecific hybrids. Among the 192 primers derived from olive flounder, 25.5% of the primer sets successfully amplified genomic DNA from starry flounder, and 23% of the 56 primer sets originating from starry flounder amplified DNA from olive flounder. Analysis of genetic inheritance in the hybrid using seven of the 62 microsatellite markers common to both species demonstrated classic Mendelian inheritance of these markers in the hybrid progeny, with the exception of one locus identified as a null allele in the hybrid. -

The United States and Japanese Counterpart Panels on Aquaculture

PREFACE TheUnited States and Japanese counterpart panels onaquaculture wereformed in 1969 under the UnitedStates-Japan Cooperative Program inNatural Resources UJNR! The panels currently include specialistsdrawnfrom the government andacadeinic departinents mostconcerned withaquaculture- Chargedwith exploring anddeveloping bilateral cooperation, thepanels have focused their efforts on exchanginginformation related to aquaculture thatcould be of benefittoboth countries. TheUJNR was begun during theThird Cabinet Level Meeting ofthe Joint United States-Japan CommitteeonTrade and Economic Affairsin January 1964,ln addition toaquaculture, currentsubjects in theprogram include toxicmicroorganisms, airpollution, energy, forage crops, national parkmanagement, rnycoplasmosis,windand seismic effects, protein resources, forestry, andseveral joint panels and corninitteesin marine resolve research, development, andutilization. Accomplishmentsiticlude:increased communication andcooperation amongtechnical specialists; exchangesofinformation, data,and research findings; annual meetings ofthe panel, a policy-coordinating body;administrative staffmeetings; exchanges ofequipment, materials, andsamples; several major technicalconferences; andbeneficial effects of internationalrelations. The26th U.S.-Japan Aquaculture PanelSyinposium washeld in Durham, New Hampshire, from16- 18September ] 997. Following thesyrnposiuin, fieldtrips during a seven-day period included theareas of Portsmouth,NewHainpshire; andBar Harbor, Eastport, Camden, and Boothbay Harbor, Maine. -

Advances in Diagnosis and Management of Amyloodiniosis in Intensive Fish Culture

ADVANCES IN DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF AMYLOODINIOSIS IN INTENSIVE FISH CULTURE Sara M. Picón-Camacho, Ignacio Masson, Reginald Blaylock * & Jeffrey Lotz Gulf Coast Research Laboratory The University of Southern Mississippi Ocean Springs, MS 39564 USA Amyloodinium ocellatum is a parasitic dinoflagellate that infects a wide variety of warmwater marine and estuarine fishes and causes one of the most serious diseases in warmwater marine fish culture. The life cycle of the parasite is direct and consists of three stages – the trophont which is parasitic primarily on the gills, the free-living reproductive tomont, and the infective dinospore. The parasite is particularly troublesome for two reasons. First, current diagnostic methods rely mainly on the microscopic identification of parasites on the skin or gills; therefore, infections often go undetected until massive mortality occurs. Second, the life cycle is direct and each tomont can produce up to 256 infective dinospores resulting in the rapid buildup of heavy infections in recirculating systems. Although the general course of infection is understood, no quantitative understanding of the survival and reproductive rates of the parasite that might lead to improved control is known. Our program has focused on strengthening our ability to address these shortcomings in diagnosis and management of amyloodiniosis. With respect to diagnosis, we developed a novel, highly sensitive and specific diagnostic tool based on the Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) reaction to detect free-swimming stages of A. ocellatum in water samples. The advantages of LAMP reaction compared to the PCR are that is quicker and does not require sophisticated equipment or skilled personnel. No amplification was detected using DNA from related dinoflagellates species, demonstrating the specificity of the assay.