The Unseen Landscape: Inventory and Assessment of Submerged Cultural Resources in Hawai`I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

The Life and Letters of a Royal Navy Surgeon, Edward Lawton Moss MD

REVIEWS • 109 why they are the crème de la crème. Chapters 7a and 7b pic- plateau of Washington Irving Island off the entrance to ture and describe some of these items. Chapter 7c, entitled Dobbin Bay on the east coast of Ellesmere Island. Much to “Gems Showcase,” is a visual feast. No fewer than 43 pages their surprise, they discovered two ancient-looking stone are devoted to images, almost all in colour, of polar material cairns on the plateau, but failed to locate any evidence of such as notices of various kinds, postcards, covers, and let- who might have built them. Moss made a quick sketch of ters. This section alone is worth the price of the book. the two cairns, a sketch he later back in England turned into The ultimate goal of many philatelists is to exhibit their a colour painting, now kept at the Scott Polar Institute in collections and, they hope, to earn a commensurate award. Cambridge. The drawing and the mention of the cairns in Chapter eight outlines the differences between showing one’s the expedition diaries resulted in our own investigation of collection and exhibiting it. Although many of the processes the plateau in July 1979. By then, numerous finds of Norse involved in showing a polar exhibit are the same as those artifacts in nearby 12th century Inuit house ruins strongly of exhibiting a general postal history collection, the author suggested that the builders of the old cairns could have been explains the differences in some detail. If an exhibit is to Norse explorers from Greenland (McCullough and Schled- do well in competition, planning, deciding what to include, ermann, 1999). -

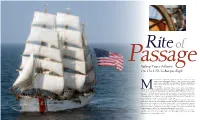

Sailing Trans-Atlantic on the USCG Barque Eagle

PassageRite of Sailing Trans-Atlantic On The USCG Barque Eagle odern life is complicated. I needed a car, a bus, a train and a taxi to get to my square-rigger. When no cabs could be had, a young police officer offered me a lift. Musing on my last conveyance in such a vehicle, I thought, My, how a touch of gray can change your circumstances. It was May 6, and I had come to New London, Connecticut, to join the Coast Guard training barque Eagle to sail her to Dublin, Ireland. A snotty, wet Measterly met me at the pier, speaking more of March than May. The spires of New Lon- don and the I-95 bridge jutted from the murk, and a portion of a nuclear submarine was discernible across the Thames River at General Dynamics Electric Boat. It was a day for sitting beside a wood stove, not for going to sea, but here I was, and somehow it seemed altogether fitting for going aboard a sailing ship. The next morning was organized chaos. Cadets lugged sea bags aboard. Human chains passed stores across the gangway and down into the deepest recesses of the ship. Station bills were posted and duties disseminated. I met my shipmates in passing and in passageways. Boatswain Aaron Stapleton instructed me in the use of a climbing harness and then escorted me — and the mayor of New London — up the foremast. By completing this evolution, I was qualified in the future to work aloft. Once stowed for sea, all hands mustered amidships. -

The Colours of the Fleet

THE COLOURS OF THE FLEET TCOF BRITISH & BRITISH DERIVED ENSIGNS ~ THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE WORLDWIDE LIST OF ALL FLAGS AND ENSIGNS, PAST AND PRESENT, WHICH BEAR THE UNION FLAG IN THE CANTON “Build up the highway clear it of stones lift up an ensign over the peoples” Isaiah 62 vv 10 Created and compiled by Malcolm Farrow OBE President of the Flag Institute Edited and updated by David Prothero 15 January 2015 © 1 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Page 3 Introduction Page 5 Definition of an Ensign Page 6 The Development of Modern Ensigns Page 10 Union Flags, Flagstaffs and Crowns Page 13 A Brief Summary Page 13 Reference Sources Page 14 Chronology Page 17 Numerical Summary of Ensigns Chapter 2 British Ensigns and Related Flags in Current Use Page 18 White Ensigns Page 25 Blue Ensigns Page 37 Red Ensigns Page 42 Sky Blue Ensigns Page 43 Ensigns of Other Colours Page 45 Old Flags in Current Use Chapter 3 Special Ensigns of Yacht Clubs and Sailing Associations Page 48 Introduction Page 50 Current Page 62 Obsolete Chapter 4 Obsolete Ensigns and Related Flags Page 68 British Isles Page 81 Commonwealth and Empire Page 112 Unidentified Flags Page 112 Hypothetical Flags Chapter 5 Exclusions. Page 114 Flags similar to Ensigns and Unofficial Ensigns Chapter 6 Proclamations Page 121 A Proclamation Amending Proclamation dated 1st January 1801 declaring what Ensign or Colours shall be borne at sea by Merchant Ships. Page 122 Proclamation dated January 1, 1801 declaring what ensign or colours shall be borne at sea by merchant ships. 2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Colours of The Fleet 2013 attempts to fill a gap in the constitutional and historic records of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth by seeking to list all British and British derived ensigns which have ever existed. -

July 2019 Whole No

Dedicated to the Study of Naval and Maritime Covers Vol. 86 No. 7 July 2019 Whole No. 1028 July 2019 IN THIS ISSUE Feature Cover From the Editor’s Desk 2 Send for Your Own Covers 2 Out of the Past 3 Calendar of Events 3 Naval News 4 President’s Message 5 The Goat Locker 6 For Beginning Members 8 West Coast Navy News 9 Norfolk Navy News 10 Chapter News 11 Fleet Week New York 2019 11 USS ARKANSAS (BB 33) 12 2019-2020 Committees 13 Pictorial Cancellations 13 USS SCAMP (SS 277) 14 One Reason Why we Collect 15 Leonhard Venne provided the feature cover for this issue of the USCS Log. His cachet marks the 75th Anniversary of Author-Ship: the D-Day Operations and the cover was cancelled at LT Herman Wouk, USNR 16 Williamsburg, Virginia on 6 JUN 2019. USS NEW MEXICO (BB 40) 17 Story Behind the Cover… 18 Ships Named After USN and USMC Aviators 21 Fantail Forum –Part 8 22 The Chesapeake Raider 24 The Joy of Collecting 27 Auctions 28 Covers for Sale 30 Classified Ads 31 Secretary’s Report 32 Page 2 Universal Ship Cancellation Society Log July 2019 The Universal Ship Cancellation Society, Inc., (APS From the Editor's Desk Affiliate #98), a non-profit, tax exempt corporation, founded in 1932, promotes the study of the history of ships, their postal Midyear and operations at this end seem to markings and postal documentation of events involving the U.S. be back to normal as far as the Log is Navy and other maritime organizations of the world. -

Download Dunes Buggy

TheSPONSORS Dunes Bug- We’d like to thank all of our contributing sponsors! Arthur Hills Golf Course • Disney’s HHI Resort George Fazio Golf Course BROAD CREEK Greenwood Communities and Resorts CAPTAIN’S MAP Leamington POA • Marriott Harbour/Sunset Pointe QUARTERS Palmetto Dunes POA • Palmetto Dunes Resort ELA’S BLUE WATER THE SHIP’S STORE ANCHORAGE Shelter Cove SHELTER COVE SHELTER COVE Palmetto Dunes General Store COMMUNITY PARK VETERANS MEMORIAL YACHT CLUB DISNEY NEWPORT Shelter Cove Lane Palmetto Dunes Tennis Center RESORT TRADEWINDS Plaza at Shelter Cove • Robert Trent Jones Golf Course HARBOURSIDE S C h I, II, III o e ve lt SHELTER COVE L er SHELTER COVE THE PLAZA AT The Dunes House • Shelter Cove Towne Centre an WATERS e EXECUTIVE TOWNE CENTRE SHELTER COVE EDGE PARK CHAMBER OF ARTS William Hilton Parkway COMMERCE CENTER Pedestrian Underpass 278 d te To Mainland To South En Security Ga WELCOME CENTER, Pedestrian Underpass 278 Interlochen Dr. CHECK"IN, RENTALS William Hilton Parkway s n er REAL ESTATE SALES LEAMINGTON st Ma Stratford Merio PDPOA PASS OFFICE, SECURITY, ADMIN LIGHTHOUSE t Lane u o Yard Fire Station b arm p A ind To Leamington Lane Up Side Fron g O! Shore W t e n i d i T Gate w k S c Niblick a l S y S rt Tack Hi t Po L gh a Wa ST. ANDREWS o W rb w a o Fu wn ll S te a weep W r o COMMON r d Wind T D at ack Brassie Ct. e Queens Queens r Leamington Ct. -

American Imperialism and the Annexation of Hawaii

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1933 American imperialism and the annexation of Hawaii Ruth Hazlitt The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hazlitt, Ruth, "American imperialism and the annexation of Hawaii" (1933). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1513. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN IMPERIALISM AND THE ANNEXATION OF liAWAII by Ruth I. Hazlitt Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. State University of Montana 1933 Approved Chairman of Examining Committee Chairman of Graduate Committee UMI Number: EP34611 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI EP34611 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest' ProQuest LLC. -

SEA8 Techrep Mar Arch.Pdf

SEA8 Technical Report – Marine Archaeological Heritage ______________________________________________________________ Report prepared by: Maritime Archaeology Ltd Room W1/95 National Oceanography Centre Empress Dock Southampton SO14 3ZH © Maritime Archaeology Ltd In conjunction with: Dr Nic Flemming Sheets Heath, Benwell Road Brookwood, Surrey GU23 OEN This document was produced as part of the UK Department of Trade and Industry's offshore energy Strategic Environmental Assessment programme. The SEA programme is funded and managed by the DTI and coordinated on their behalf by Geotek Ltd and Hartley Anderson Ltd. © Crown Copyright, all rights reserved Document Authorisation Name Position Details Signature/ Initial Date J. Jansen van Project Officer Checked Final Copy J.J.V.R 16 April 07 Rensburg G. Momber Project Specialist Checked Final Copy GM 18 April 07 J. Satchell Project Manager Authorised final J.S 23 April 07 Copy Maritime Archaeology Ltd Project No 1770 2 Room W1/95, National Oceanography Centre, Empress Dock, Southampton. SO14 3ZH. www.maritimearchaeology.co.uk SEA8 Technical Report – Marine Archaeological Heritage ______________________________________________________________ Contents I LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................5 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................7 1. NON TECHNICAL SUMMARY................................................................................8 1.1 -

Southward an Analysis of the Literary Productions of the Discovery and Nimrod Expeditions to Antarctica

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) In LLEAP – Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali Tesi di Laurea Southward An analysis of the literary productions of the Discovery and Nimrod Expeditions to Antarctica. Relatore Ch. Prof. Emma Sdegno Laureando Monica Stragliotto Matricola 820667 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 Chapter I The History of Explorations in Antarctica 8 Chapter II Outstanding Men, Outstanding Deeds 31 Chapter III Antarctic Journals: the Models 46 Chapter IV Antarctic Journals: Scott’s Odyssey and Shackleton’s Personal Attempt 70 Chapter V The South Polar Times and Aurora Australis: Antarctic Literary Productions 107 CONCLUSION 129 BIBLIOGRAPHY 134 2 INTRODUCTION When we think about Antarctica, we cannot help thinking of names such as Roald Admunsen, Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton. These names represented the greatest demonstration of human endurance and courage in exploration and they still preserve these features today. The South Pole represented an unspoilt, unknown, unexplored area for a long time, and all the Nations competed fiercely to be the first to reach the geographical South Pole. England, which displays a great history of exploration, contributed massively to the rush to the Antarctic especially in the first decade of the 20th century. The long years spent in the Antarctic by the British explorers left a priceless inheritance. First of all, the scientific fields such as meteorology, geology and zoology were tellingly improved. The study of the ice sheet allowed the scientists of the time to partly explain the phenomenon of glaciations. In addition, magnetism was still a new field to be explored and the study of phenomena such as the aurora australis and the magnetic pole as a moving spot1 were great discoveries that still influence our present knowledge. -

Schofield Barracks

ARMY ✭✭ AIR FORCE ✭✭ NAVY ✭✭ MARINES ONLINE PORTAL Want an overview of everything military life has to offer in Hawaii? This site consolidates all your benefits and priveleges and serves all branches of the military. ON BASE OFF BASE DISCOUNTS • Events Calendar • Attractions • Coupons & Special Offers • Beaches • Recreation • Contests & Giveaways • Attractions • Lodging WANT MORE? • Commissaries • Adult & Youth Go online to Hawaii • Exchanges Education Military Guide’s • Golf • Trustworthy digital edition. • Lodging Businesses Full of tips on arrival, • Recreation base maps, phone • MWR numbers, and websites. HawaiiMilitaryGuide.com 4 Map of Oahu . 10 Honolulu International Airport . 14 Arrival . 22 Military Websites . 46 Pets in Paradise . 50 Transportation . 56 Youth Education . 64 Adult Education . 92 Health Care . 106 Recreation & Activities . 122 Beauty & Spa . 134 Weddings. 138 Dining . 140 Waikiki . 148 Downtown & Chinatown . 154 Ala Moana & Kakaako . 158 Aiea/West Honolulu . 162 Pearl City & Waipahu . 166 Kapolei & Ko Olina Resort . 176 Mililani & Wahiawa . 182 North Shore . 186 Windward – Kaneohe . 202 Windward – Kailua Town . 206 Neighbor Islands . 214 6 PMFR Barking Sands,Kauai . 214 Aliamanu Military Reservation . 218 Bellows Air Force Station . 220 Coast Guard Base Honolulu . 222 Fort DeRussy/Hale Koa . 224 Fort Shafter . 226 Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam . 234 MCBH Camp Smith . 254 MCBH Kaneohe Bay . 258 NCTAMS PAC (JBPHH Wahiawa Annex) . 266 Schofield Barracks . 268 Tripler Army Medical Center . 278 Wheeler Army Airfield . 282 COVID-19 DISCLAIMER Some information in the Guide may be compromised due to changing circumstances. It is advisable to confirm any details by checking websites or calling Military Information at 449-7110. HAWAII MILITARY GUIDE Publisher ............................Charles H.