(24 Cm, XVII, 420). ISBN 978-0-19-815250-7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scarabs and Cylinders with Names

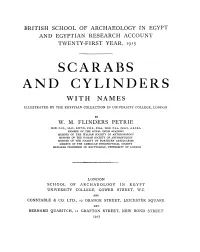

BRITISH SCHOOL OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN EGYPT AND EGYPTIAN RESEARCH ACCOUNT TWENTY-FIRST YEAR, 1915 SCARABS AND CYLINDERS WITH NAMES ILLUSTRATED BY THE EGYPTIAN COLLECTION IN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, LONDON BY W. M. FLINDERS PETRIE HON. D.C.L., LL.D., L1TT.D.. F.R.S., F.B.A., HON. F.S.A. (SCOT.), A.R.I.B.A. MEMBER OF THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY MEMBER OF THE ITALIAN SOCIETY OF ANTHROPOLOGY MEMBER OF THE ROMAN SOCIETY OF ANTHROPOLOGY MEMBER OF THE SOCIETY OF NORTHERN ANTIQUARIES MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN PIIILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY BDWARDS PROFESSOR OF EGYPTOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON LONDON SCHOOL OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN EGYPT UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, GOWER STREET, W.C. AND CONSTABLE (G CO. LTD., 10 ORANGE STREET, LEICESTER SQUARE AND BERNARD QUARITCH, 11 GRAFTON STREET, NEW BOND STREET '917 PRINTED BY =*=ELL, WATSON AND VINEY, L~., LONDON AND AYLESBURY. BRITISH SCHOOL OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN EGYPT AND EGYPTIAN RESEARCH ACCOUNT GENERAL COMMITTEE (*Bxecutiz~z ibfenibsus) Hon. JOHN ABERCROMBY Prof. PERCYGARDNCR *J. G. MILNE WALTERRALLY Rt. Hon. Sir G. T. GOLDIE KOBERTMOND HENRYBALFOUR Prof. GOWLAND Prof. MONTAGUE Rev. Dr. T. G. BONNEY Mrs. J. R. GREEN WALTERMORRISON Prof. R. C. BOSANQUET Rt. Hon. F.-M. LORDGRENFELL *Miss M. A. MURRAY Rt. Hon. VISCOIJNT BRYCEOF Mrs. F. LL. GRIFFITH Prof. P. E. NEWBERRY DECHMONT Dr. A. C. HADDON His Grace the DUKE OF Dr. R. M. BURROWS Dr. JESSE HAWORTH NORTHUMBERLAND. "Prof. J. B. BURY(Cliairr~~an) Rev. Dr. A. C. HEADLAM F. W. PERCIVAL *SOMERSCLARKE D. G. HOGARTH Dr. PINCHES EowARn CLODD Sir H. H. HOWORTH Dr. G. W. PROTHERO Prof. BOYDDAWKINS Baron A. -

Magic in Ancient Egypt *ISBN 0292765592*

MAGIC IN ANCIENT EGYPT Geraldine Pinch British Museum Press © 1994 Geraldine Pinch Published by British Museum Press A division of British Museum Publications 46 Bloomsbury Street, London WCiB 3QQ British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record of this tide is available from the British Library ISBN O 7141 0979 I Designed by Behram Kapadia Typeset by Create Publishing Services Printed in Great Britain by The Bath Press, Avon COVER Detail of faience plaque showing the protective lion-demon, Bes, c. ist century AD. FRONTISPIECE and BACK COVER One of the giant baboon statues in the area of the ruined temple of Thoth at Hermopolis, I4th century BC. Hermopolis was famous as a centre of magical knowledge. Contents Acknowledgements 7 1 EGYPTIAN MAGIC 9 2 MYTH AND MAGIC 18 3 DEMONS AND SPIRITS 3 3 4 MAGICIANS AND PRIESTS 47 5 WRITTEN MAGIC 61 6 MAGICAL TECHNIQUES 76 7 MAGIC FIGURINES AND STATUES 90 8 AMULETS 104 9 FERTILITY MAGIC 120 10 MEDICINE AND MAGIC 133 11 MAGIC AND THE DEAD 147 12 THE LEGACY OF EGYPTIAN MAGIC 161 Glossary 179 Notes 181 Bibliography 183 Illustration Acknowledgements 18 6 Index 187 Acknowledgements o general book on Egyptian magic can be written without drawing on the specialised knowledge of many scholars, and N most particularly on the work of Professor J. F. Borghouts and his pupils at Leiden. The recent translations of the Graeco-Egyptian magical papyri by a group of scholars including H. D. Betz and J. H. Johnson are essential reading for anyone interested in Egyptian magic. I gratefully acknowledge the inspiration provided by a seminar series on Egyptian magic held at Cambridge University in 1991; especially the contributions of John Baines, Janine Bourriau, Mark Collier and John Ray. -

Early Dynastic Egypt

EARLY DYNASTIC EGYPT EARLY DYNASTIC EGYPT Toby A.H.Wilkinson London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. © 1999 Toby A.H.Wilkinson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Wilkinson, Toby A.H. Early Dynastic Egypt/Toby A.H.Wilkinson p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p.378) and index. 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C. I. Title DT85.W49 1999 932′.012–dc21 98–35836 CIP ISBN 0-203-02438-9 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-20421-2 (Adobe e-Reader Format) ISBN 0-415-18633-1 (Print Edition) For Benjamin CONTENTS List of plates ix List of figures x Prologue xii Acknowledgements xvii PART I INTRODUCTION 1 Egyptology and the Early Dynastic Period 2 2 Birth of a Nation State 23 3 Historical Outline 50 PART II THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AUTHORITY 4 Administration 92 5 Foreign Relations 127 6 Kingship 155 7 Royal Mortuary Architecture 198 8 Cults and -

Us Vs. Them: Dualism and the Frontier in History

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2004 Us vs. them: Dualism and the frontier in history. Jonathan Joseph Wlasiuk The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Wlasiuk, Jonathan Joseph, "Us vs. them: Dualism and the frontier in history." (2004). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5242. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5242 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes” or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author’s Signature: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author’s explicit consent. 8/98 US VS. THEM: DUALISM AND THE FRONTIER IN HISTORY by Jonathan Joseph Wlasiuk B.A. The Ohio State University, 2002 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana April 2004 Approved by: lairperson Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP40706 AH rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

On-Going Investigations at the Predynastic to Early Dynastic Site of Kafr Hassan Dawood: Copper, Exchange and Tephra

On-going Investigations at the Predynastic to Early Dynastic site of Kafr Hassan Dawood: Copper, Exchange and Tephra Fekri A. Hassan, Université française d’Égypte, Cairo, Egypt Geoffrey J. Tassie, TOPOI Excellence Cluster, Freie Universität, Berlin, Germany Thilo Rehren, UCL Qatar, Qatar Joris van Wetering, United Kingdom1 Continued analysis of material – primarily for certain graves dug into this layer in the ceramic – excavated during the 1990s at the south of the site that did not have any grave Predynastic to Early Dynastic cemetery site goods and has also given a terminus ante quem of Kafr Hassan Dawood (KHD) in the Wadi for all the graves below this layer. Archaeomet- Tumilat has allowed seven phases of use to be allurgical analysis of a copper bowl from grave identifi ed. Th is process has been greatly helped 913 has shown that it was made of arsenical by the acquisition of further archival material copper, which probably came from the Sinai. of the 1989 to 1995 excavations. Th e assigning Th e large amount of copper artefacts found at of these phases was also aided by the dating KHD may indicate its function as a node on of tephra from a layer covering First Dynasty the interregional exchange network between graves; it has provided a terminus post quem the Sinai and the Memphite region. 1. Thanks to Dr Victoria Smith (University of Oxford, Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art) for her analysis of the tephra and Prof. Arlene Rosen (Department of Anthropology, University of Texas at Austin) for her analysis of the phytoliths. -

Thinking About Archeoastronomy

Thinking about Archeoastronomy Noah Brosch The Wise Observatory and the Raymond and Beverly Sackler School of Physics and Astronomy, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69972, Israel Abstract I discuss various aspects of archeoastronomy concentrating on physical artifacts (i.e., not including ethno-archeoastronomy) focusing on the period that ended about 2000 years ago. I present examples of artifacts interpreted as showing the interest of humankind in understanding celestial phenomena and using these to synchronize calendars and predict future celestial and terrestrial events. I stress the difficulty of identifying with a high degree of confidence that these artifacts do indeed pertain to astronomy and caution against the over-interpretation of the finds as definite evidence. With these in mind, I point to artifacts that seem to indicate a human fascination with megalithic stone circles and megalithic alignments starting from at least 11000 BCE, and to other items presented as evidence for Neolithic astronomical interests dating to even 20000 BCE or even before. I discuss the geographical and temporal spread of megalithic sites associated with astronomical interpretations searching for synchronicity or for a possible single point of origin. A survey of a variety of artifacts indicates that the astronomical development in antiquity did not happen simultaneously at different locations, but may be traced to megalithic stone circles and other megalithic structures with possible astronomical connections originating in the Middle East, specifically in the Fertile Crescent area. The effort of ancient societies to erect these astronomical megalithic sites and to maintain a corpus of astronomy experts does not appear excessive. Key words: archeoastronomy, megaliths, stone circles, alignments Introduction This paper deals with “archeoastronomy” in a restricted sense. -

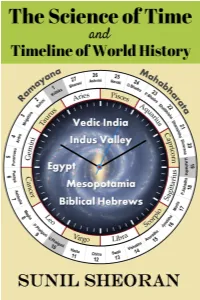

The Science of Time and Timeline of World History (Sunil Sheoran, 2017).Pdf

The Science of Time and Timeline of World History The Science of Time and Timeline of World History SUNIL SHEORAN eBook Edition v.1.0.0.1 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Sunil Sheoran All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. However, this book is available to download for free in PDF format as an eBook that may not be reverse- engineered or copied, printed and sold for any commercial gains. But it may be printed for personal and non-commercial educational use in its original form, without any modification to its contents or structure. First English Edition 2017 (eBook v.1.0.0.1) Price: –0.00/– Sunil Sheoran Bhiwani, Haryana India - 127021 TheScienceOfTime.com Facebook: fb.com/thescienceoftime Twitter: twitter.com/Science_of_Time Email: tsotbook [at] gmail.com Prayer नमकृ तं महादवे ं िशवं सयं योगेरम् । I salute the great god Śiva, embodiment of truth & ultimate Yogī. नमकृ तं उमादवे महामाया महकारणम् ॥ 1 I salute Umā, the great illusory power & first principle of creation. नमकृ तं दवनायके ं पावकं मयूरवािहनम् । I salute the general of gods, the fiery one who rides a peacock. नमकृ तं अदवे ं सुमुखं ासायलेखकम् ॥ 2 I salute the first-worshipped, of beautiful face & the writer of Vyāsa. -

Manetón Y La Dinastía II. Pistas Sobre Las Dinámicas De Poder a Comienzos De La Historia Egipcia

XVI Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Departamento de Historia. Facultad Humanidades. Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata, 2017. Manetón y la Dinastía II. Pistas sobre las dinámicas de poder a comienzos de la historia egipcia. Zulian, Marcelo. Cita: Zulian, Marcelo (2017). Manetón y la Dinastía II. Pistas sobre las dinámicas de poder a comienzos de la historia egipcia. XVI Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Departamento de Historia. Facultad Humanidades. Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/000-019/2 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. Manetón y la Dinastía II. Pistas sobre las dinámicas de poder a comienzos de la historia egipcia. Zulian, Marcelo. UM, CIUNSa. PARA PUBLICAR EN ACTAS El conflicto entre los poderes locales y los poderes nacionales1 fue una constante a lo largo de la historia del Antiguo Egipto, pero es en el periodo inmediatamente posterior a la unificación, conocido como Dinástico Temprano, cuando esta realidad se mostró más desnuda. Hace unos años presenté un trabajo en el que analizaba la distribución de las tumbas reales de la Dinastía I para concluir que, al menos hacia comienzos de la unificación, las lealtades locales predinásticas seguían vigentes (ZULIAN, 2013). En el presente trabajo la intención es profundizar en el conocimiento de esta dinámica a través del análisis de la cronología de la Dinastía II. -

SETH – a MISREPRESENTED GOD in the ANCIENT EGYPTIAN PANTHEON? a Thesis Submitted to the University of Manchester for the Degre

SETH – A MISREPRESENTED GOD IN THE ANCIENT EGYPTIAN PANTHEON ? A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Life Sciences. 2012 Philip John Turner 2 1. C ontent s 3 1.1 List of Figures 6 2. Abst ract 7 3. Introduction 13 3 .1 Egyptian Religion 13 3 .2 Scholarship on Seth 14 3.2.1 Seth: Name, Iconography and Character 15 3 .3 Research Problem/Questions 1 8 4 . Seth in Predynastic Egypt 4400 -3100 B.C.E. 21 4 .1 Introduction 21 4.2 The Badarian culture in Ancient Egypt 21 4 . 3 The Amratian (Naqada I) culture in Ancient Egypt 22 4 . 4 The Gerzean (Naqada II) culture in Ancient Egypt 2 5 4.5 Summary 2 9 5. The Early Dynastic Period and the Old Kingdom 3100 to 2181 B.C.E. 32 5.1 Introduction 32 5 . 2 The Unification of Egypt 32 5 . 3 The First Dynasty 33 5 . 4 The Second Dynasty 3 5 5 . 5 The Old Kingdom 3 6 5.6 Seth and the Pyramid Texts 40 5.6.1 The negative texts (69 in number , 9.1% ) 42 5.6.2 The positive texts (20 in number , 2.6 %) 43 5.6.3 The neutral texts (44 in number , 5.8% ) 4 3 5.7 The Sixth Dynasty 4 4 5.8 Summary 4 4 6. The First Intermediate Period and Middle Ki ngdom 2181 -1782 B.C.E. 4 6 6.1 Introduction 4 6 6.2 The S event h D ynas t y 4 6 6.3 The Ei ght h and Nineth Dynasties 4 8 6.4 The Tent h Dynas t y 4 8 6.5 The El eventh D ynas t y 4 8 6.6 The Twel fth Dynasty 4 9 6.7 The C o ffin Tex ts 51 6.7.1 The negative texts (72 in number , 6.0% ) 52 6.7.2 The posi tive t exts (27 in number , 2.0% ) 53 6.7.3 The neutral tex ts (32 in numbe r, 3.0% ) 53 6.8 Summary 53 7. -

PERÍODO DINASTÍA AÑO FARAÓN HECHOS IMPORTANTES Período Dinástico Temprano I 2950-2750 A.C Narmer Aha Dyer Dyet Den Anedji

CRONOLOGÍA PERÍODO DINASTÍA AÑO FARAÓN HECHOS IMPORTANTES Período I 2950-2750 a.C Narmer Unificación del Alto y Bajo Dinástico Aha Egipto Temprano Dyer Dyet Den Anedjib Semerjet Qaa II 2750-2650 a.C Hetepsekhemuny Nebra Nynetjer Weneg Sened Peribsen Jasejemuy III 2650-2575 a.C Djoser (Zoser) -Construcción de la Sejemjet pirámide escalonada de Saqqara. Jaba Sanajt o Nebka Huny Imperio Antiguo IV 2575-2450 a.C Esnefru (Snefru) -Apogeo de construcción Khufu (Keops) de pirámides. -Construcción de la Gran Djedefra Pirámide de Giza. Khafra (Kefrén) -Se termina la Gran Nebka II Esfinge. Menkaure (Micerino) Shepseskaf Thamphthis V 2450-2325 a.C Userkaf -Templos consagrados al Sahura sol. -Recopilación de los Neferirkara Kakai Textos de las Pirámides. Shepseskara Isi Neferefra Nyuserra Iny Menkauhor Dyedkara Isesi Unis (Unas) Mg. Elizabeth Noreña www.egiptologiamedellin.com CRONOLOGÍA VI 2325-2175 a.C Teti Userkara Pepi I Merenra Neferkara Pepi II VII Numerosos estudiosos cuestionaron la existencia de esta dinastía. El historiador Manetón describió esta época como “Caótica”. Fue un período de 70 gobernantes en 70 días. VIII 2175-2125 a.C Dieciocho reyes efímeros, entre ellos: Nemtyemsaf II Neithikerty Siptah Ibi Neferkaura Neferkauhor Neferirkara Primer Período IX/X 2125-1975 a.C Varios reyes, entre -En estas dinastías se dio Intermedio ellos: gran auge del culto a Osiris. Jety I Jety II Merykara XI (Primera 2080-1938 a.C Mentuhotep I -Estalla la guerra civil. Mitad) Intef I Intef II Intef III Imperio Medio XI (Segunda 2010-1842 a.C Mentuhotep II -Termina la guerra civil; Mitad) Mentuhotep III Egipto reunificado. Qakare Intef Sekhentibre Menekhkare Mentuhotep IV XII 1938-1755 a.C Amenemhat I -Florece la Literatura. -

The Menkaure Dyad(S) 109

Egypt and Beyond. Essays Presented to Leonard H. Lesko Leonard H. Lesko, in his office at Brown University ii 001-frontmatter.indd 2 2/29/08 6:06:52 PM Egypt and Beyond. Essays Presented to Leonard H. Lesko Egypt and Beyond Essays Presented to Leonard H. Lesko upon his Retirement from the Wilbour Chair of Egyptology at Brown University June 2005 Edited by Stephen E. Thompson and Peter Der Manuelian Department of Egyptology and Ancient Western Asian Studies Brown University 2008 iii 001-frontmatter.indd 3 2/29/08 6:06:52 PM Egypt and Beyond. Essays Presented to Leonard H. Lesko Typeset in New Baskerville Copyedited, typeset, designed, and produced by Peter Der Manuelian i s b n 13: 978-0-9802065-0-0 i s b n 10: 0-9802065-0-2 © 2008 Department of Egyptology and Ancient Western Asian Studies, Brown University All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher Printed in the United States of America by Sawyer Printers, Charlestown, Massachusetts Bound by Acme Bookbinding, Charlestown, Massachusetts iv 001-frontmatter.indd 4 2/29/08 6:06:52 PM Egypt and Beyond. Essays Presented to Leonard H. Lesko Contents Pr e f a c e b y st e P h e n e. th o m P s o n vii Li s t o f contributors ix ba r b a r a s. -

List of Pharaohs

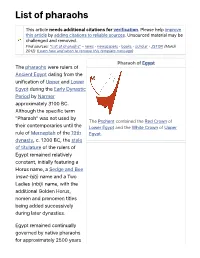

List of pharaohs This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "List of pharaohs" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Pharaoh of Egypt The pharaohs were rulers of Ancient Egypt dating from the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt during the Early Dynastic Period by Narmer approximately 3100 BC. Although the specific term "Pharaoh" was not used by The Pschent combined the Red Crown of their contemporaries until the Lower Egypt and the White Crown of Upper rule of Merneptah of the 19th Egypt. dynasty, c. 1200 BC, the style of titulature of the rulers of Egypt remained relatively constant, initially featuring a Horus name, a Sedge and Bee (nswt-bjtj) name and a Two Ladies (nbtj) name, with the additional Golden Horus, nomen and prenomen titles being added successively during later dynasties. Egypt remained continually governed by native pharaohs for approximately 2500 years until it was conquered by the Kingdom of Kush in the late 8th century BC, whose rulers adopted the traditional pharaonic titulature for themselves. Following the Kushite conquest, Egypt would first see another period of independent native rule before being conquered by the Achaemenid Empire, whose rulers also adopted the title of "Pharaoh". The last native Pharaoh of Egypt was Nectanebo II, who was Pharaoh A typical depiction of a pharaoh. before the Achaemenids Details conquered Egypt for a second time. Style Five-name titulary First monarch Narmer (a.k.a.