42749 Classic Serpent 140Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ayout 1 7/8/11 07:42 Page 1

Guild 306 text pages:Layout 1 7/8/11 07:42 Page 1 wDasava ihdighly Horoiginlat l Jungian thinker. He was born into a Liverpool Shipping family in 1926. After war service on Atlantic and Russian convoys in 1944, and in the Pacific in 1945, he read Modern History at Oxford, with the study of St. Augustine his special subject. Following on eleven years in book and newspaper publishing, he graduated from the C.G.Jung Institute in Zurich (1962-1966) with a thesis on ‘Persona and Actor’. From 1971 to 1982 he taught and supervised at the Westminster Pastoral Foundation, where he introduced the Counselling and Ontology course. He led the interdisciplinary theatrical weekends on Jung and Hermeneutics at Hawkwood College in Gloucestershire, from 1978 – 1991. His rendering of Wall in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is particularly remembered. He was passionately interested in the work of the Guild of Pastoral Psychology, Chair in 1970 and from 1988 – 1992 he was Chair of the C.G.Jung Analytical Psychology Club in London. He died on Easter Sunday, 2002. His thinking about the importance of the Guild is well-recorded both in the pamphlet Idolatry and Work in Psychology, in the 1970 Annual report (also published in the format of a Guild pamphlet) and in the 1990 History of the Guild by Ann Shearer and Michael Anderton. David resigned after one year but his apparent ‘failure’ can be seen partially 1 Guild 306 text pages:Layout 1 7/8/11 07:42 Page 2 as a ‘success’ since the Council moved from being a self-appointing oligarchy to a body at least partially elected by the membership. -

Association for Transpersonal Psychology

Volume 51 Association for PSYCHOLOGY TRANSPERSONAL OF THE JOURNAL Number 1, 2019 Transpersonal Psychology Membership Includes: One-year subscription to The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology (two issues) ATP Newsletter Editor’s Note v Professional Members Listing A Memorial Tribute to Ralph Metzner: Scholar, Listings of Schools and Programs Teacher, Shaman (18 May 1936 to 14 March 2019) David E. Presti 1 * Membership Dues: Regular—$75 per year Scientism and Empiricism in Transpersonal Psychology Paul Cunningham 6 Professional—$95 per year Vaccination with Kambo Against Bad Influences: Jan M. Keppel Student—$55 per year Processes of Symbolic Healing and Ecotherapy Hesselink, Michael Supporting—$175 per year Winkelman 28 The Meaning of an Initiation Ritual in a Giovanna Calabrese, Further Information: Descriptive brochure and Psychotherapy Training Course Giulio Rotonda, Pier membership forms available Luigi Lattuada 49 upon request Transcending “Transpersonal”: Time to Join the World Jenny Wade 70 Religious or Spiritual Problem? The Clinical Association for Transpersonal Psychology Relevance of Identifying and Measuring Spiritual Kylie P. Harris, Adam J. P.O. Box 50187 Emergency 89 VOLUME 51 VOLUME Rock, Gavin I. Clark Palo Alto, California 94303 This Association is a Division of the Transpersonal Institute, Book Reviews a Non-Profit Tax-Exempt Organization. The Sacred Path of the Therapist: Modern Healing, Ancient 119 Wisdom, and Client Transformation. Irene R. Siegel Irene Lazarus The Red Book Hours: Discovering C.G. Jung’s Art Mediums Visit the ATP and Journal Web page 124 NUMBER 1 and Creative Process. Jill Mellick Janice Geller at Psychology Without Spirit: The Freudian Quandary. Samuel 127 www.atpweb.org Bendeck Sotillos Binita Mehta Books Our Editors Are Reading: A Retrospective The website has more detailed information and ordering forms * View The second decade (1980-1989) 132 for membership (including international), subscriptions, JTP CD Archive, ATP’s other publications, 2019 and a chronological list of Journal articles, 1969 to the current volume. -

The Psychological Search for a Science of Religion (1896-1937)

Theorizing experience: the psychological search for a science of religion (1896-1937) Matei George Iagher University College London PhD History of Medicine 2016 1 DECLARATION I, Matei George Iagher, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed:.................................................................................................................... Date:........................................................................................................................ 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the central projects for a psychology of religion put forward in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It argues that the proponents of this sub- discipline were attempting to set up a new science of religion, one which they thought was radically different from the science(s) of religion(s) that had been created in the second half of the nineteenth century by thinkers such as Max Müller, C.P.Tiele, E.B. Tylor, or Albert Réville. The novelty of the psychology of religion was thought to reside in its identification of a primarily affective and pre-intellectual religious experience as the essence of religion and in the development of tools (e.g. questionnaires) and concepts (e.g. conversion, mysticism) with which to probe that experience. After a period of efflorescence in the first two decades of the twentieth century, the psychology of religion began declining in the 1930s. I argue that this decline was, in part, the result of an inability to maintain the theoretical integrity of the psychology of religion's topic of study, such that the discipline either became dissolved into general psychology or it became a private theology in its own right. -

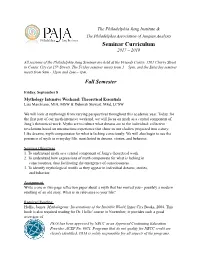

2017-2018 Seminar Curriculum (PDF)

The Philadelphia Jung Institute & The Philadelphia Association of Jungian Analysts Seminar Curriculum 2017 – 2018 All sessions of the Philadelphia Jung Seminar are held at the Friends Center, 1501 Cherry Street in Center City (at 15th Street). The Friday seminar meets from 1 – 5pm, and the Saturday seminar meets from 9am - 12pm and 1pm – 4pm. Fall Semester Friday, September 8 Mythology Intensive Weekend: Theoretical Essentials Lisa Marchiano, MIA, MSW & Deborah Stewart, MEd, LCSW We will look at mythology from varying perspectives throughout this academic year. Today, for the first part of our myth-intensive weekend, we will focus on myth as a central component of Jung’s theoretical work. Myths are to culture what dreams are to the individual: collective revelations based on unconscious experience that show us our shadow projected into a story. Like dreams, myth compensates for what is lacking consciously. We will also begin to see the presence of myth in everyday life, manifested in dreams, stories, and behavior. Seminar Objectives 1. To understand myth as a central component of Jung’s theoretical work. 2. To understand how expressions of myth compensate for what is lacking in consciousness, thus facilitating the emergence of consciousness. 3. To identify mythological motifs as they appear in individual dreams, stories, and behavior. Assignment Write a one or two page reflection paper about a myth that has moved you-- possibly a modern retelling of an old story. What is its relevance to your life? Required Reading Hollis, James. Mythologems: Incarnations of the Invisible World, Inner City Books, 2004. This book is also required reading for Dr. -

{FREE} Korean Hangul Practice Notebook

KOREAN HANGUL PRACTICE NOTEBOOK : HANGUL PRACTICE BOOK, KOREAN HANGUL PRACTICE BOOK, KOREAN ALPHABET WORKBOOK, KOREAN LANGUAGE WORKBOOK, CUTE MONSTERS COVER Author: Rogue Plus Publishing Number of Pages: 104 pages Published Date: 07 May 2018 Publisher: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform Publication Country: none Language: English ISBN: 9781718834019 DOWNLOAD: KOREAN HANGUL PRACTICE NOTEBOOK : HANGUL PRACTICE BOOK, KOREAN HANGUL PRACTICE BOOK, KOREAN ALPHABET WORKBOOK, KOREAN LANGUAGE WORKBOOK, CUTE MONSTERS COVER Korean Hangul Practice Notebook : Hangul Practice Book, Korean Hangul Practice Book, Korean Alphabet Workbook, Korean Language Workbook, Cute Monsters Cover PDF Book js is required. The book's blend of cutting-edge theory with visceral events means that it will be particularly useful for illuminating urban courses within geography, sociology, planning, anthropology, political science, public policy, architecture and technology studies. Spain is different with its climate, laid back lifestyle and cheaper cost of living. Are they really able to rely upon luck. The dominant wireless standards; including cellular, cordless and wireless LANs; are discussed. Hydrogen in Intermetallic Compounds I: Electronic, Thermodynamic, and Crystallographic Properties, PreparationHydrogen in Intermetallics I is the first of two volumes aiming to provide atutorial introduction to the general topic of hydrogen in intermetallic compounds and alloys. 0 book on the market and a definitive guide to the major innovation in EJB: the new persistence API Offers unparalleled insight and expertise: lead authored by the co-lead on the EJB 3. The book explores the sacred places of India, taking the reader on an extraordinary trip through the beliefs and history of this rich and profound place, as well as providing a basic introduction to Hindu religious ideas and how those ideas influence our understanding of the modern sense of -India- as a nation. -

Chapter Eight Reducing Social Inequality

1 OWNERSHIP CAUSES SOCIAL INEQUALITY. TO REDUCE SOCIAL INEQUALITY, REDUCE OR DIFFUSE OWNERSHIP AN ANALYSIS WITH PARTICULAR APPLICATION TO THE COPYRIGHT SYSTEM BENEDICT ATKINSON BA (Hons) LLB LLM (Research Hons 1) University of Sydney A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Australian Catholic University 2015 2 TO MY PARENTS Ave atque vale I thank my supervisors Professor Brian Fitzgerald and Dr John Gilchrist for the effort they made on my behalf and their excellent counsel. 3 STATEMENT OF SOURCES/ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP The work has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher education institution. The work is original and does not reproduce work previously published by me. I cite in some footnotes in the text published works of which I am the author or a joint-author. Citations are specific and complete, and details of the works are also reproduced in the bibliography. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this dissertation does not reproduce material previously published or written by another person except where attribution or reference is made. Signature Date 4 ABSTRACT Humans contest for control or ownership. Contest is to a considerable extent inescapable because conceptually a large part of most grammars involve possession and appropriation. Language creates antithesis (‘mine, yours’) that results in conflict. The result of conflict is possession and dispossession, which results in ownership, which is expressed in property and property systems. This dissertation focuses on the exclusionary effect of property systems. Property confers the power to exclude and the aggregate of legal exclusions, which constitutes a property system, objectively or instrumentally creates social exclusion and thus social inequality. -

A Semi-Annual Publication of the Philem N Foundation

a semi-annual publication of the Spring 2005 philem n foundation Volume 1, Issue 1 JUNG HISTORY: A Semi-Annual Publication of the FOUNDATION PROJECTS Philemon Foundation, Volume 1, Issue 1 THE JUNG-WHITE LETTERS : PAGE TWO Murray Stein The Philemon Foundation was founded at the end of EXCERPT FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2003, and since this time, has made critical contribu- TO THE JUNG-WHITE LETTERS : PAGE FOUR tions to a number of ongoing projects preparing for Ann Lammers publication the still unpublished works of C. G. Jung. The Foundation is grateful to its donors who have MODERN PSYCHOLOGY : PAGE EIGHT made this work possible. Jung History, which will Sonu Shamdasani appear semi-annually, will provide accounts of some SWISS FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY of the ongoing research supported by the Philemon (ETH): COLLATING THE TEXT OF THE Foundation and other news. In addition to schol- “MODERN PSYCHOLOGY” : PAGE TWELVE ars funded by the Philemon Foundation, Jung History Angela Graf-Nold will present reports of significant historical research and publications in the field. In recent years, an ADDITIONAL PROJECTS increasing amount of new historical research on C. G. A NEW JUNG BIBLIOGRAPHY : PAGE SIXTEEN Jung has been undertaken, based on the study of Juliette Vieljeux hitherto unknown primary materials. However, the publication of such research has been widely dis- PICTURING JUNG’S PLACES : PAGE NINETEEN persed, which has led to the desirability of a publica- Dieter Klein tion to gather together such work and make it better known. Jung History sets out to fill this need. Jung NEWS : PAGE TWENTY ONE History will be freely distributed to donors, collabo- rating institutions, and interested readers. -

Libraryworking List

The C G Jung Society of Queensland Library List AUTHOR TITLE Abrams J Ed. Reclaiming The Inner Child Adler, G Jaffe, A Selected Letters of CG Jung, 1909-1961 Allan J & Bertoia J Written Paths to Healing Allione, T Women of Wisdom Ammann, R Healing & Transformation in Sandplay Armstrong, K English Mystics of the 14th Century, The Avens, R Imagination is Reality New Gnosis, The Blair, D Jung: A Biography Baynes, H G Mythology of the Soul Bedi, A Path to the Soul Awakening theSlumbering Goddess Retire your Family Karma Beer, B Mystics Yesterday and Today: The Love that Connects Us All Bell, D Daughters of the Dreaming Bly, R Iron John: A Book About Men Bly, R & Woodman, M Maiden King, The Boer, C Trans. Homeric Hymns, The Bond, D Archetype of Renewal Bosnak, R Little Course in Dreams, A Tracks in the Wilderness of Dreaming Breaux, C Journey Into Consciousness Brinton - Perera, S Scapegoat Complex, The: Towards a Mythology of Shadow and Guilt Descent to the Goddess Browne, L Many Faces of Coincidence, The Burland, CA Magical Arts, The: A Short History Caldwell, C Getting our Bodies Back Campbell, J Creative Mythology: The Masks of God Hero With a Thousand Faces, The Campbell, J Ed. Spirit and Nature, Papers from Eranos Yearbooks, 01 The Mysteries, Papers from Eranos Yearbooks, 02 Man and Time, Papers from Eranos Yearbooks, 03 Man and Transformation, Papers from Eranos Yearbooks, 05 Carotenuto, A Eros and Pathos: Shades of Love and Suffering Clark, J In Search of Jung: Historical and Philosophical Enquiries Claxton, G Beyond Therapy: Impact -

Hemingway's Francis Macomber In

Journal of Jungian Scholarly Studies Vol. 9, No. 5, 2014 Hemingway’s Francis Macomber in “God’s Country” Matthew A. Fike, Ph.D. Winthrop University In 1925−26, C. G. Jung’s Bugishu Psychological Expedition journeyed through Kenya, the setting of Ernest Hemingway’s “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” Although the two authors went to Africa for vastly different reasons, Jung’s insights into the personal and collective unconscious, along with the discoveries he made while there, provide a lens through which to complement previous Freudian and Lacanian studies of the story. Francis, a puer aeternus and introverted thinker, overcomes his initial mother complex by doing shadow work with his hunting guide, Robert Wilson. As the story progresses, Francis makes the unconscious more conscious through dreaming and then connects with the archaic/primordial man buried deeply below his modern civilized persona. The essay thus resolves two long-standing critical cruxes: the title character makes genuine psychological progress; and his wife, whether she shoots at the buffalo or at him, targets primordial masculine strength. In Death in the Afternoon, Ernest Hemingway states: “If a writer of prose knows enough about what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water” (192).1 “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” one of two stories that arose from Hemingway’s African safari, is a fine illustration of the “ice-berg” principle. -

Psychologie Analytique 1 Psychologie Analytique

Psychologie analytique 1 Psychologie analytique La psychologie analytique (« Analytische Psychologie » en allemand) est une théorie élaborée par le psychiatre Carl Gustav Jung dès 1913. Elle est avant tout une démarche propre au psychiatre suisse, créée pour la différencier de celle de Sigmund Freud[1] , et qui se propose de faire l'investigation de l'inconscient et de l'âme, c'est-à-dire la « psyché ». L'histoire de la psychologie analytique est ainsi intimement liée à la biographie de Jung. Représentée dans ses débuts par l'« école de Zurich », avec Eugen Bleuler, Franz Riklin, Alphonse Maeder et Jung, la psychologie analytique est d'abord une théorie des complexes, jusqu'à ce que Jung, dès sa rupture avec Freud, en fasse une méthode d'investigation générale des archétypes et de l'inconscient, ainsi qu'une psychothérapie spécifique. La psychologie analytique, ou « psychologie complexe » (« Komplexe Psychologie » en allemand), est à l'origine de nombreux développements, en psychologie comme dans d'autres disciplines. Les continuateurs de Jung sont en effet nombreux, et organisés en sociétés nationales dans le monde. Les applications et développements des postulats posés par Jung ont donné Allégorie alchimique extraite de l'Alchimie de Nicolas Flamel, par le Chevalier Denys Molinier, XVIIIe siècle. naissance à une littérature dense et multidisciplinaire. La faisant reposer sur une conception objective de la psyché, Jung a établi sa théorie en développant des concepts clés du domaine de la psychologie et de la psychanalyse, tels celui d'inconscient collectif, d'archétype ou de synchronicité. Elle se distingue par sa prise en compte des mythes et traditions, révélateurs de la psyché, de toutes les époques et de tous les continents, par le rêve comme élément central de communication avec l'inconscient et par l'existence d'instances psychiques autonomes comme l'anima pour l'homme ou l'animus pour la femme, la persona ou l'ombre, communs aux deux sexes. -

James Hillman Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8vh5tns No online items James Hillman Papers Finding aid prepared by Archives Staff Opus Archives and Research Center 801 Ladera Lane Santa Barbara, CA, 93108 805-969-5750 [email protected] http://www.opusarchives.org © 2021 James Hillman Papers 1 Descriptive Summary Title: James Hillman Collection Physical Description: 140 linear feet (231 boxes) Repository: Opus Archives and Research Center Santa Barbara, CA 93108 Language of Material: English Biography/Organization History James Hillman (1926-2011) was an American psychologist, among the founding thinkers of archetypal psychology, and a leading scholar in Jungian and post-Jungian thought. Born in Atlantic City in 1926, Hillman served in the US Navy Hospital Corps for two years during World War II. Following the end of the war, he attended the Sorbonne in Paris, and Trinity College in Dublin. Hillman then received his Doctoral Degree from the University of Zürich and completed his training as a Jungian analyst in 1959 at the C. G. Jung Institute Zürich, becoming the Institute’s Director of Studies the same year, a position he held for ten years (1959-1969). In 1970, Hillman became the editor of Spring Journal, a publication dedicated to psychology, philosophy, mythology, arts, humanities, and cultural issues. Upon becoming the Dean of Graduate Studies at the University of Dallas, he moved to the United States, and co-founded the Dallas Institute for Humanities and Culture in 1978. He also held teaching positions at Yale University, the University of Chicago, and Syracuse University. Hillman published more than nineteen books, as well as volumes of essays, and continued to be a prolific writer and sought after lecturer until his death in 2011. -

Animus: the Spirit of Inner Truth in Women Free

FREE ANIMUS: THE SPIRIT OF INNER TRUTH IN WOMEN PDF Emmanuel Kennedy-Zypolitas,Barbara Hannah | 240 pages | 15 Apr 2012 | Chiron Publications | 9781888602470 | English | Wilmette IL, United States The Animus: The Spirit of Inner Truth in Women, Vol 2 ePUB Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. Barbara Hannah was a straightforward, modest-yet-grand woman, a lover of literature, and a colleague and friend Animus: The Spirit of Inner Truth in Women C. She lectured extensively in Switzerland and England and wrote several books on C. Jung and Jungian psychology. These two volumes present her psychological analysis of the animus gleaned from handwritten notes, typed manuscripts, previously published articles, her own drafts of her lectures, and notes taken by those present. She tackled the theme of the animus with a comprehensiveness unsurpassed in Jungian literature. Her insight and vigor stem from a personal grappling with her own animus while integrating the experience and reflections of many psychotherapists who were working directly with C. Authenticity and comprehensiveness were priorities in editing this work as well as preserving the excellence and comprehensiveness of her work on the animus—a most complex and vexing topic—while rendering the wonderful natural spirit of Barbara Hannah herself. Barbara Hannah — was born in England. A close associate of Jung until his death, she Animus: The Spirit of Inner Truth in Women a practicing psychotherapist and lecturer at the C.