The Psychological Search for a Science of Religion (1896-1937)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Reviews Religious Syncretism and Deviance in Islamic And

Turkish Historical Review 3 (2012) 91–113 brill.nl/thr Book Reviews Religious syncretism and deviance in Islamic and Christian orthodoxies Angeliki Konstantakopoulou * Gilles Veinstein (ed.), Syncrétisme religieux et déviances de l’Orthodoxie chré- tienne et islamique. Syncrétismes et hérésies dans l’Orient Seldjoukide et Ottoman (XIVe-XVIIIe siècle), Actes du Colloque du Collège de France, Octobre 2001 (Paris: Peeters, 2005) (Collection Turcica, vol. 9), pp. 428, ISBN 904 2 915 49 8. Various aspects of the question of religious syncretism in the Middle East have repeatedly been the subject of research. Seen from an ‘orientalist’ and idealistic point of view, this question has been dealt with by national historiographies in a predictably justifi catory fashion. Moreover, after the end of the Cold War era, it resurfaced, integrated into wider questions such as that of the politicisa- tion of religion or that of the emergence of “ethnic-identities”, an issue which has recently engulfed the institutions of the European Union. In the current enfl amed situation, the historian has diffi culty in detaching himself/herself from the crucial present debate on religion/culture and confl icts (dictated as an almost exclusive approach and topic of research according to the lines of the ‘clash of civilizations’ theory). Often encountering retrospective and anachronistic interpretations, (s)he needs to revisit, among other issues, the question of the religious orthodoxies and of the deviances from them. Th e collective work presented here is, in short, an attempt to explore respective phenomena in their own historical terms. Th e participants at the Colloque of the Collège de France in October 2001 developed new analyses and proposed responses to an historical phenomenon which is linked in various ways to cur- rent political-ideological events (Preface by Gilles Veinstein, pp xiii-xiv). -

Heretical Networks Between East and West: the Case of the Fraticelli

Heretical Networks between East and West: The Case of the Fraticelli NICKIPHOROS I. TSOUGARAKIS Abstract: This article explores the links between the Franciscan heresy of the Fraticelli and the Latin territories of Greece, between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. It argues that the early involvement of Franciscan dissidents, like Angelo Clareno, with the lands of Latin Romania played an important role in the development of the Franciscan movement of dissent, on the one hand by allowing its enemies to associate them with the disobedient Greek Church and on the other by establishing safe havens where the dissidents were relatively safe from the persecution of the Inquisition and whence they were also able to send missionaries back to Italy to revive the movement there. In doing so, the article reviews all the known information about Fraticelli communities in Greece, and discovers two hitherto unknown references, proving that the sect continued to exist in Greece during the Ottoman period, thus outlasting the Fraticelli communities of Italy. Keywords: Fraticelli; Franciscan Spirituals; Angelo Clareno; heresy; Latin Romania; Venetian Crete. 1 Heretical Networks between East and West: The Case of the Fraticelli The flow of heretical ideas between Byzantium and the West is well-documented ever since the early Christian centuries and the Arian controversy. The renewed threat of popular heresy in the High Middle Ages may also have been influenced by the East, though it was equally fuelled by developments in western thought. The extent -

Part I the Beginnings

Part I The Beginnings 1 The Problem of Heresy Heresy, and the horror it inspires, intertwines with the history of the Church itself. Jesus warned his disciples against the false prophets who would take His name and the Epistle to Titus states that a heretic, after a first and second abomination, must be rejected. But Paul, writing to the Corinthians, said, `Oportet esse haereses', as the Latin Vulgate translated his phrase ± `there must be heresies, that they which are proved may be manifest among you'1 ± and it was understood by medieval churchmen that they must expect to be afflicted by heresies. Heresy was of great importance in the early centuries in forcing the Church progressively to define its doctrines and to anathematize deviant theological opinions. At times, in the great movements such as Arianism and Gnosticism, heresy seemed to overshadow the Church altogether. Knowledge of the individ- ual heresies and of the definitions which condemned them became a part of the equipment of the learned Christian; the writings of the Fathers wrestled with these deviations, and lists of heresies and handbooks assimilated this experience of the early centuries and handed it on to the Middle Ages. Events after Christianity became the official religion of the Empire also shaped the assumptions with which the Church of the Middle Ages met heresy. After Constantine's conversion, Christians in effect held the power of the State and, despite some hesitations, they used it to impose a uniformity of belief. Both in the eastern and in the western portions of the Empire it became the law that pertinacious heretics were subject to the punishments of exile, branding, confis- cation of goods, or death. -

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Heresy Description Origin Official

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Official Heresy Description Origin Other Condemnation Adoptionism Belief that Jesus Propounded Theodotus was Alternative was born as a by Theodotus of excommunicated names: Psilanthro mere (non-divine) Byzantium , a by Pope Victor and pism and Dynamic man, was leather merchant, Paul was Monarchianism. [9] supremely in Rome c.190, condemned by the Later criticized as virtuous and that later revived Synod of Antioch presupposing he was adopted by Paul of in 268 Nestorianism (see later as "Son of Samosata below) God" by the descent of the Spirit on him. Apollinarism Belief proposed Declared to be . that Jesus had by Apollinaris of a heresy in 381 by a human body Laodicea (died the First Council of and lower soul 390) Constantinople (the seat of the emotions) but a divine mind. Apollinaris further taught that the souls of men were propagated by other souls, as well as their bodies. Arianism Denial of the true The doctrine is Arius was first All forms denied divinity of Jesus associated pronounced that Jesus Christ Christ taking with Arius (ca. AD a heretic at is "consubstantial various specific 250––336) who the First Council of with the Father" forms, but all lived and taught Nicea , he was but proposed agreed that Jesus in Alexandria, later exonerated either "similar in Christ was Egypt . as a result of substance", or created by the imperial pressure "similar", or Father, that he and finally "dissimilar" as the had a beginning declared a heretic correct alternative. in time, and that after his death. the title "Son of The heresy was God" was a finally resolved in courtesy one. -

Ayout 1 7/8/11 07:42 Page 1

Guild 306 text pages:Layout 1 7/8/11 07:42 Page 1 wDasava ihdighly Horoiginlat l Jungian thinker. He was born into a Liverpool Shipping family in 1926. After war service on Atlantic and Russian convoys in 1944, and in the Pacific in 1945, he read Modern History at Oxford, with the study of St. Augustine his special subject. Following on eleven years in book and newspaper publishing, he graduated from the C.G.Jung Institute in Zurich (1962-1966) with a thesis on ‘Persona and Actor’. From 1971 to 1982 he taught and supervised at the Westminster Pastoral Foundation, where he introduced the Counselling and Ontology course. He led the interdisciplinary theatrical weekends on Jung and Hermeneutics at Hawkwood College in Gloucestershire, from 1978 – 1991. His rendering of Wall in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is particularly remembered. He was passionately interested in the work of the Guild of Pastoral Psychology, Chair in 1970 and from 1988 – 1992 he was Chair of the C.G.Jung Analytical Psychology Club in London. He died on Easter Sunday, 2002. His thinking about the importance of the Guild is well-recorded both in the pamphlet Idolatry and Work in Psychology, in the 1970 Annual report (also published in the format of a Guild pamphlet) and in the 1990 History of the Guild by Ann Shearer and Michael Anderton. David resigned after one year but his apparent ‘failure’ can be seen partially 1 Guild 306 text pages:Layout 1 7/8/11 07:42 Page 2 as a ‘success’ since the Council moved from being a self-appointing oligarchy to a body at least partially elected by the membership. -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

The Movement of the Free Spirit

The Movement of the Free Spirit Raoul Vaneigem General Considerations and Firsthand Testimony Concerning Some Brief Flowerings of Life in the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and, Incidentally, Our Own Time ZONE BOOKS ' NEW YORK UHIB The publisher would like to thank Donald Nicholson-Smith for his assistance in the production of this book. Ian Patterson would like to thank Dr. James Simpson, of Robinson Col lege, Cambridge, for his generous help with the translation of Margaret Porete's French. © 1994 Urzone, Inc. ZONE BOOKS 611 Broadway, Suite 60S New York, NY 10012 First Paperback Edition All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, includ ing electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise (except for that copying permitted by Sections 107 and lOS of the u.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the Publisher. Originally published in France as Le Mouvement du libre-esprit © 19S6 Editions Ramsay. Printed in the United States of America. Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vaneigem, Raoul, 1934- [Mouvement du Libre-Esprit. English] The Movement of the Free Spirit: general considerations and firsthand testimony concerning some brief flowerings of life in the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and, incidentally, our own time / Raoul Vaneigem; translated by Randall Cherry and Ian Patterson. p. cm. Tr anslation of: Mouvement du Libre-Esprit. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-942299-71-X I. Brethren of the Free Spirit. -

The Year 1909 in Church History the Presidential Address by Francis Albert Christie

The Year 1909 in Church History The Presidential Address By Francis Albert Christie 151 THE YEAR 1909 IN CHURCH HISTORY. BY FRANCIS ALBERT CHRISTIE, PROFESSOR CHURCH HIS- TORY, MEADVILLE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, MEADVILLE, PA. (The Presidential Address, read December 30, iQog) "THE convent annalist in darker ages had slight sense of ••• proportion and value in what he recorded. We, too, even in days of journalistic publicity, may not know the real significance of the day's happenings and the year's record is arbitrary until results apportion value. We do not know whether the high celebrations of institutional life or some simple deed or word hid in obscurity to us shall be to after times the great mark of our year. Our first thought must be of farewells spoken sadly and reverently for those who have been faithful doers in our engrossing tasks and now have ceased from their labor. For us the first remembrance is of James William Richard, Henry Charles Lea, Adolph Haus- rath, and last of all George Park Fisher, and what they achieved will carry their memory into years far distant. The death also of Father George Tyrrell wakens poignant regret in all who have viewed his spiritual chivalry in the most re- cent struggle within the Roman Church. The year has been calamitously marked also in modern annals by the shocking massacre of Christians in Adana and Tarsus in the month of April, an atrocity relieved only by the fact that it was instigated in futile reaction against a reform of the Turkish Constitution and so may mark the end of an evil day. -

Association for Transpersonal Psychology

Volume 51 Association for PSYCHOLOGY TRANSPERSONAL OF THE JOURNAL Number 1, 2019 Transpersonal Psychology Membership Includes: One-year subscription to The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology (two issues) ATP Newsletter Editor’s Note v Professional Members Listing A Memorial Tribute to Ralph Metzner: Scholar, Listings of Schools and Programs Teacher, Shaman (18 May 1936 to 14 March 2019) David E. Presti 1 * Membership Dues: Regular—$75 per year Scientism and Empiricism in Transpersonal Psychology Paul Cunningham 6 Professional—$95 per year Vaccination with Kambo Against Bad Influences: Jan M. Keppel Student—$55 per year Processes of Symbolic Healing and Ecotherapy Hesselink, Michael Supporting—$175 per year Winkelman 28 The Meaning of an Initiation Ritual in a Giovanna Calabrese, Further Information: Descriptive brochure and Psychotherapy Training Course Giulio Rotonda, Pier membership forms available Luigi Lattuada 49 upon request Transcending “Transpersonal”: Time to Join the World Jenny Wade 70 Religious or Spiritual Problem? The Clinical Association for Transpersonal Psychology Relevance of Identifying and Measuring Spiritual Kylie P. Harris, Adam J. P.O. Box 50187 Emergency 89 VOLUME 51 VOLUME Rock, Gavin I. Clark Palo Alto, California 94303 This Association is a Division of the Transpersonal Institute, Book Reviews a Non-Profit Tax-Exempt Organization. The Sacred Path of the Therapist: Modern Healing, Ancient 119 Wisdom, and Client Transformation. Irene R. Siegel Irene Lazarus The Red Book Hours: Discovering C.G. Jung’s Art Mediums Visit the ATP and Journal Web page 124 NUMBER 1 and Creative Process. Jill Mellick Janice Geller at Psychology Without Spirit: The Freudian Quandary. Samuel 127 www.atpweb.org Bendeck Sotillos Binita Mehta Books Our Editors Are Reading: A Retrospective The website has more detailed information and ordering forms * View The second decade (1980-1989) 132 for membership (including international), subscriptions, JTP CD Archive, ATP’s other publications, 2019 and a chronological list of Journal articles, 1969 to the current volume. -

October-2003.Pdf

CONCORDIA JOURNAL Volume 29 October 2003 Number 4 CONTENTS EDITORIALS Editor’s Note ........................................................................ 354 A Faculty Statement ............................................................. 356 Theological Potpourri ........................................................... 358 Theological Observers ............................................................ 363 ARTICLES The Beginnings of the Papacy in the Early Church Quentin F. Wesselschmidt ........................................................ 374 Antichrist?: The Lutheran Confessions on the Papacy Charles P. Arand .................................................................. 392 The Papacy in Perspective: Luther’s Reform and Rome Robert Rosin ........................................................................ 407 Vatican II’s Conception of the Papacy: A Lutheran Response Richard H. Warneck ............................................................. 427 Ut Unum Sint and What It Says about the Papacy: Description and Response Samuel H. Nafzger ............................................................... 447 Papacy as a Constitutive Element of Koinonia in Ut Unum Sint? Edward J. Callahan ............................................................... 463 HOMILETICAL HELPS .................................................................. 483 BOOK REVIEWS ............................................................................... 506 BOOKS RECEIVED .......................................................................... -

Catharism and the Tarot," Robert V

- 1 - Special Studies in Tarot and Moonstruck present CCAATTHHAARRIISSMM AANNDD TTHHEE TTAARROOTT BBYY RROOBBEERRTT VV.. OO''NNEEIILLLL Introduction Chapter 8 in Tarot Symbolism (O'Neill, 1986) considered the possible contribution of heretic sects to the design of the 15th century Tarot. Since 1986, academic interest in intellectual history in general and esoteric history in particular has produced an entire scholarly library on the late Medieval heretics. The abundance of new studies permits a re-examination of the question and leads to some rather different conclusions than were possible in the book. Interest in Catharism as a source of imagery arises because of the numerous symbols of dualism in the Tarot: pairs of pillars and pitchers, male/female duals, etc. Catharism, known as Albigensianism in southern France, was fundamentally a dualist heresy that inherited many concepts from the ancient Gnostics. Bayley (1912) hypothesized that the watermarks of French papermakers contained heretical symbols. Waite (1911) suggested the watermarks as a source of Tarot symbols, based on Bayley's 1909 paper "New Light on the Renaissance." The idea of heretical origins for the Tarot still attracts attention because the Medieval heresies share two important traits with modern Tarotists. First, there is a rebellion against any authoritative imposition of dogma. Cathari and most Tarotists see - 2 - self-development, spirituality, and mysticism as an individual and personal quest. Second, they both share a sense of the emergence of a new age of peace and fulfillment. This feeling of like-mindedness seems to reinforce the internal evidence for dualism in the symbols. Intuitively, heretical origins for the Tarot feels comfortable. -

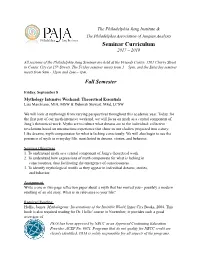

2017-2018 Seminar Curriculum (PDF)

The Philadelphia Jung Institute & The Philadelphia Association of Jungian Analysts Seminar Curriculum 2017 – 2018 All sessions of the Philadelphia Jung Seminar are held at the Friends Center, 1501 Cherry Street in Center City (at 15th Street). The Friday seminar meets from 1 – 5pm, and the Saturday seminar meets from 9am - 12pm and 1pm – 4pm. Fall Semester Friday, September 8 Mythology Intensive Weekend: Theoretical Essentials Lisa Marchiano, MIA, MSW & Deborah Stewart, MEd, LCSW We will look at mythology from varying perspectives throughout this academic year. Today, for the first part of our myth-intensive weekend, we will focus on myth as a central component of Jung’s theoretical work. Myths are to culture what dreams are to the individual: collective revelations based on unconscious experience that show us our shadow projected into a story. Like dreams, myth compensates for what is lacking consciously. We will also begin to see the presence of myth in everyday life, manifested in dreams, stories, and behavior. Seminar Objectives 1. To understand myth as a central component of Jung’s theoretical work. 2. To understand how expressions of myth compensate for what is lacking in consciousness, thus facilitating the emergence of consciousness. 3. To identify mythological motifs as they appear in individual dreams, stories, and behavior. Assignment Write a one or two page reflection paper about a myth that has moved you-- possibly a modern retelling of an old story. What is its relevance to your life? Required Reading Hollis, James. Mythologems: Incarnations of the Invisible World, Inner City Books, 2004. This book is also required reading for Dr.