The Waldensians, the Hussites and the Bohemian Brethren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Reviews Religious Syncretism and Deviance in Islamic And

Turkish Historical Review 3 (2012) 91–113 brill.nl/thr Book Reviews Religious syncretism and deviance in Islamic and Christian orthodoxies Angeliki Konstantakopoulou * Gilles Veinstein (ed.), Syncrétisme religieux et déviances de l’Orthodoxie chré- tienne et islamique. Syncrétismes et hérésies dans l’Orient Seldjoukide et Ottoman (XIVe-XVIIIe siècle), Actes du Colloque du Collège de France, Octobre 2001 (Paris: Peeters, 2005) (Collection Turcica, vol. 9), pp. 428, ISBN 904 2 915 49 8. Various aspects of the question of religious syncretism in the Middle East have repeatedly been the subject of research. Seen from an ‘orientalist’ and idealistic point of view, this question has been dealt with by national historiographies in a predictably justifi catory fashion. Moreover, after the end of the Cold War era, it resurfaced, integrated into wider questions such as that of the politicisa- tion of religion or that of the emergence of “ethnic-identities”, an issue which has recently engulfed the institutions of the European Union. In the current enfl amed situation, the historian has diffi culty in detaching himself/herself from the crucial present debate on religion/culture and confl icts (dictated as an almost exclusive approach and topic of research according to the lines of the ‘clash of civilizations’ theory). Often encountering retrospective and anachronistic interpretations, (s)he needs to revisit, among other issues, the question of the religious orthodoxies and of the deviances from them. Th e collective work presented here is, in short, an attempt to explore respective phenomena in their own historical terms. Th e participants at the Colloque of the Collège de France in October 2001 developed new analyses and proposed responses to an historical phenomenon which is linked in various ways to cur- rent political-ideological events (Preface by Gilles Veinstein, pp xiii-xiv). -

The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy

The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy: Through the Eyes Adam Giancola of the Waldensian Experience The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy: Through the Eyes of the Waldensian Experience Adam Giancola In the wake of the Protestant Reformation, the experience of many countries across Europe was the complete overturning of traditional institutions, whereby religious dissidence became a widespread phenomenon. Yet the focus on Reformation history has rarely been given to countries like Italy, where a strong Catholic presence continued to persist throughout the sixteenth century. In this regard, it is necessary to draw attention to the ‘Italian Reformation’ and to determine whether or not the ideas of the Reformation in Western Europe had any effect on the religious and political landscape of the Italian peninsula. In extension, there is also the task to understand why the Reformation did not ‘succeed’ in Italy in contrast to the great achievements it made throughout most other parts of Western Europe. In order for these questions to be addressed, it is necessary to narrow the discussion to a particular ‘Protestant’ movement in Italy, that being the Waldensians. In an attempt to provide a general thesis for the ‘failure’ of the Protestant movement throughout Italy, a particular look will be taken at the Waldensian case, first by examining its historical origins as a minority movement pre-dating the European Reformation, then by clarifying the Waldensian experience under the sixteenth century Italian Inquisition, and finally, by highlighting the influence of the Counter-Reformation as pivotal for the future of Waldensian survival. Perhaps one of the reasons why the Waldensian experience differed so greatly from mainstream European reactions has to do with its historical development, since in many cases it pre-dated the rapid changes of the sixteenth century. -

Heretical Networks Between East and West: the Case of the Fraticelli

Heretical Networks between East and West: The Case of the Fraticelli NICKIPHOROS I. TSOUGARAKIS Abstract: This article explores the links between the Franciscan heresy of the Fraticelli and the Latin territories of Greece, between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. It argues that the early involvement of Franciscan dissidents, like Angelo Clareno, with the lands of Latin Romania played an important role in the development of the Franciscan movement of dissent, on the one hand by allowing its enemies to associate them with the disobedient Greek Church and on the other by establishing safe havens where the dissidents were relatively safe from the persecution of the Inquisition and whence they were also able to send missionaries back to Italy to revive the movement there. In doing so, the article reviews all the known information about Fraticelli communities in Greece, and discovers two hitherto unknown references, proving that the sect continued to exist in Greece during the Ottoman period, thus outlasting the Fraticelli communities of Italy. Keywords: Fraticelli; Franciscan Spirituals; Angelo Clareno; heresy; Latin Romania; Venetian Crete. 1 Heretical Networks between East and West: The Case of the Fraticelli The flow of heretical ideas between Byzantium and the West is well-documented ever since the early Christian centuries and the Arian controversy. The renewed threat of popular heresy in the High Middle Ages may also have been influenced by the East, though it was equally fuelled by developments in western thought. The extent -

A Theological Journal•Xlv 2003•I

Communio viatorumA THEOLOGICAL JOURNAL•XLV 2003•I Jan Hus – a Heretic, a Saint, or a Reformer? • The White Mountain, 1620: An Annihilation or Apotheosis of Utraquism? • Close Encounters of the Pietistic Kind: The Moravian-Methodist • Connection by Vilém Herold, Zdeněk V. David, Ted A. Campbell published by charles university in prague, protestant theological faculty Communio CONTENTS (XLV, 2003) Nr. 1 1 . DAVID HOLETON Communio Viatorum and International Scholarship on the Bohemian Reformation 5 . VILÉM HEROLD Jan Hus – a Heretic, a Saint, or a Reformer? 24 . ZDENĚK V. DAVID The White Mountain, 1620: An Annihilation or Apotheosis of Utraquism? 67 . TED A. CAMPBELL Close Encounters of the Pietistic Kind: The Moravian-Methodist Connection BOOK REVIEWS 81 . PAVEL HOŠEK Beyond Foundationalism 86 . TIM NOBLE Sacred Landscapes and Cultural Politics viatorum a theological journal Published by Charles University in Prague, Protestant Theological Faculty Černá 9, 115 55 Praha 1, Czech Republic. Editors: Peter C. A. Morée, Ivana Noble, Petr Sláma Typography: Petr Kadlec Printed by Arch, Brno Administration: Barbara Kolafová ([email protected]) Annual subscription (for three issues): 28 or the equivalent in Europe, 30 USD for overseas. Single copy: 10 or 11 USD. Please make the payment to our account to: Bank name: Česká spořitelna Address: Vodičkova 9, 110 00, Praha 1, Czech Republic Account no.: 1932258399/0800 Bank identification code (SWIFT, BLZ, SC, FW): GIBA CZPX Orders, subscriptions and all business correspondence should be adressed to: Communio viatorum Černá 9 P. O. Box 529 CZ-115 55 Praha 1 Czech Republic Phone: + + 420 221 988 205 Fax: + + 420 221 988 215 E- mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.etf.cuni.cz/cv.html (ISSN 0010-3713) IČO vydavatele (ETF UK, Černá 9, 115 55 Praha 1) 00216208. -

"For Yours Is the Kingdom of God": a Historical Analysis of Liberation Theology in the Last Two Decades and Its Significance Within the Christian Tradition

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 "For Yours is the Kingdom of God": A historical analysis of liberation theology in the last two decades and its significance within the Christian tradition Virginia Irby College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Irby, Virginia, ""For Yours is the Kingdom of God": A historical analysis of liberation theology in the last two decades and its significance within the Christian tradition" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 288. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/288 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “For Yours is the Kingdom of God:” A historical analysis of liberation theology in the last two decades and its significance within the Christian tradition A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Religious Studies from The College of William and Mary by Virginia Kathryn Irby Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ John S. Morreall, Director ________________________________________ Julie G. Galambush ________________________________________ Tracy T. Arwari Williamsburg, VA April 29, 2009 This thesis is dedicated to all those who have given and continue to give their lives to the promotion and creation of justice and peace for all people. -

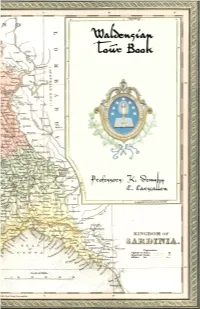

Waldensian Tour Guide

1 ii LUX LUCET EN TENEBRIS The words surrounding the lighted candle symbolize Christ’s message in Matthew 5:16, “Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your father who is in heaven.” The dark blue background represents the night sky and the spiritual dark- ness of the world. The seven gold stars represent the seven churches mentioned in the book of Revelation and suggest the apostolic origin of the Waldensian church. One oak tree branch and one laurel tree branch are tied together with a light blue ribbon to symbolize strength, hope, and the glory of God. The laurel wreath is “The Church Triumphant.” iii Fifth Edition: Copyright © 2017 Original Content: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout Redesign:Luis Rios First Edition Copyright © 2011 Published by: School or Architecture Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI 49104 Compiled and written: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout and Design: Kathleen Demsky & David Otieno Credits: Concepts and ideas are derived from my extensive research on this history, having been adapted for this work. Special credit goes to “The Burning Bush” (Captain R. M. Stephens) and “Guide to the Trail of Faith” (Maxine McCall). Where there are direct quotes I have given credit. Web Sources: the information on the subjects of; Fortress Fenestrelle, Arch of Augustus, Fortress of Exhilles and La Reggia Veneria Reale ( Royal Palace of the Dukes of Savoy) have been adapted from GOOGLE searches. Please note that some years the venue will change. iv WALDENSIAN TOUR GUIDE Fifth EDITION BY KATHLEEN M. DEMSKY v Castelluzzo April 1655 Massacre and Surrounding Events, elevation 4450 ft The mighty Castelluzzo, Castle of Light, stands like a sentinel in the Waldensian Valleys, a sacred monument to the faith and sacrifice of a people who were willing to pay the ultimate price for their Lord and Savior. -

Century Historiography of the Radical Reformation

Toward a Definition of Sixteenth - Century habaptism: Twentieth - Century Historiography of the Radical Reformation James R. Coggins Winnipeg "To define the essence is to shape it afresh." - Ernst Troeltsch Twentieth-century Anabaptist historiography has somewhat of the character of Hegelian philosophy, consisting of an already established Protestant-Marxist thesis, a Mennonite antithesis and a recent synthesis. The debate has centred on three major and related issues: geographic origin, intellectual sources, and essence. Complicating these issues has been confusion over the matter of categorization: Just who is to be included among the Anabaptists and who should be assigned to other groups? Indeed, what are the appropriate categories, or groups, in the sixteenth century? This paper will attempt to unravel some of the tangled debate that has gone on concerning these issues. The Protestant interpretation of Anabaptism has the longest aca- demic tradition, going back to the sixteenth century. Developed by such Protestant theologians and churchmen as Bullinger, Melanchthon, Men- ius, Rhegius and Luther who wrote works defining and attacking Ana- baptism, this interpretation arose out of the Protestant understanding of the church. Sixteenth-century Protestants believed in a single universal church corrupted by the Roman Catholic papacy but reformed by them- selves. Anyone claiming to be a Christian but not belonging to the church Joitnlal of Mennonite Stitdies Vol. 4,1986 184 Journal ofMennonite Studies (Catholic or Protestant) was classed as a heretic,' a member of the mis- cellaneous column of God's sixteenth-century army. For convenience all of these "others" were labelled "Anabaptists." Protestants saw the Anabaptists as originating in Saxony with Thomas Muntzer and the Zwickau prophets in 1521 and spreading in subsequent years to Switzerland and other parts of northern Europe. -

Anabaptist Influences on World Christianity

Anabaptist Influences on World Christianity Howard F. Shipps* The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century had many sources. Some of these, like springs and streams leading toward a grand river, may be found several centuries before the time of Martin Luther. Such beginnings may be seen in the Cathari and the Walden- ses of the twelfth century. During the succeeding centuries of the late middle ages, similar movements of revolt and insistence upon purification of the established church continued to multiply and grow. More and more these new forces attracted the attention of all Europe. They arose in widely scattered geographical areas and represented various cultures and different levels of medieval society. There were the Christian mystics of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Eckhart, Tauler, Suso, Merswin and the "Friends of God," seeking earnestly for life's greatest reality�the knowledge of God's presence in the soul of man. Likewise there were the Brethren of the Common Life of the fourteenth century, Groot, Ruysbroeck, Radewyn and a' Kempis, who were seeking to find God amidst the common ways of secular pursuits and by a daily practice of His Presence. During the same century, but across the English Channel, John Wy- cliffe was delivering the Word of God from the enslavement of tradi tion and the prison house of the so-called sacred Latin language, preaching and printing it in the tongue of the common man. He also made this living Word incarnate by committing it to men who would declare it throughout the by-ways of England. Thus for more than a century the Lollards carried the torch of truth which would urge the masses throughout England toward one of their greatest awakenings. -

Reconstruction Or Reformation the Conciliar Papacy and Jan Hus of Bohemia

Garcia 1 RECONSTRUCTION OR REFORMATION THE CONCILIAR PAPACY AND JAN HUS OF BOHEMIA Franky Garcia HY 490 Dr. Andy Dunar 15 March 2012 Garcia 2 The declining institution of the Church quashed the Hussite Heresy through a radical self-reconstruction led by the conciliar reformers. The Roman Church of the late Middle Ages was in a state of decline after years of dealing with heresy. While the Papacy had grown in power through the Middle Ages, after it fought the crusades it lost its authority over the temporal leaders in Europe. Once there was no papal banner for troops to march behind to faraway lands, European rulers began fighting among themselves. This led to the Great Schism of 1378, in which different rulers in Europe elected different popes. Before the schism ended in 1417, there were three popes holding support from various European monarchs. Thus, when a new reform movement led by Jan Hus of Bohemia arose at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the declining Church was at odds over how to deal with it. The Church had been able to deal ecumenically (or in a religiously unified way) with reforms in the past, but its weakened state after the crusades made ecumenism too great a risk. Instead, the Church took a repressive approach to the situation. Bohemia was a land stained with a history of heresy, and to let Hus's reform go unchecked might allow for a heretical movement on a scale that surpassed even the Cathars of southern France. Therefore the Church, under guidance of Pope John XXIII and Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg, convened in the Council of Constance in 1414. -

Anabaptism in Historical Perspective

EDITORIAL Anabaptism in Historical Perspective Kenneth Cain Kinghorn* Perhaps one of the most glaring injustices in ecclesiastical historiography has been the frequent failure to see the responsible and worthwhile elements in the dissenting movements within Prot estantism. The prevalent attitude toward Anabaptists may be regard ed as a classic illustration of this phenomenon. For centuries the Anabaptists have been lumped together with the irresponsible "spiri tualists" of the Reformation, the radical Anti-Trinitarians, and other fringe movements. Many church historians have seen only evil in any movement which has not been consistent with Wittenberg, Zurich or Geneva. The Anabaptists have frequently been regarded as only a negation of the gains of the Reformation. This attitude has tended to persist in a widespread way because of the paucity of writing on the Anabaptists by sympathetic schol 1 ars. However, since the mid-nineteenth century, this traditionally negative view has been greatly modified. (This changing mood is often seen as beginning with Max Gobel in his Geschichte des christleichn Lebens in der rheinisch-westfalischen. Kirche.) This leads one to a basic question as to the meaning of the term "Anabaptist." The late Harold S. Bender, a distinguished Anabap tist scholar, points out the difference between the original,evangel ical and constructive Anabaptist movement and the various mysti cal, spiritualistic, revolutionary, or even antinomian groups which have been concurrent. 2 The former is represented by the Mennonite and the latter maybe represented by such as the Schw'drmer, Thomas * Associate Professor of Church History, Asbury Theological Seminary. 1. See John Christian Wenger, Even Unto Death (Richmond: John Knox Press, 1961), pp. -

The Radical Reformation New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Division of Theological and Historical Studies Spring 2020 - Thursday, 6:00-8:50 Pm

HIST 6313 The Radical Reformation New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Division of Theological and Historical Studies Spring 2020 - Thursday, 6:00-8:50 pm Dr. Mark E. Foster Adjunct Professor Office: Hardin Student Center, in the Registrar’s Office Phone: (504) 282-4455 ext. 3297 Email: [email protected] This course begins on January 23, 2020 , and on that date students should have access to Blackboard, where they will find information and instructions about the course. Prior to that time, students should purchase the texts and be ready to participate in the course. The reading schedule is included in this syllabus so that, once students have secured the textbooks, they can begin reading their assignments. Mission Statement New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and Leavell College prepare servants to walk with Christ, proclaim His truth, and fulfill His mission. Purpose of the Course The purpose of this course is to provide quality theological education for students in the discipline of theological and historical studies. Lessons learned from the past inform the present and provide guidance for the future. Core Value Focus The seminary has five core values: Doctrinal Integrity, Spiritual Vitality, Mission Focus, Characteristic Excellence, and Servant Leadership. This academic year, the core value is Spiritual Vitality – “We are a worshiping community emphasizing both personal spirituality and gathering together as a Seminary family for the praise and adoration of God and instruction in His Word.” Curriculum Competencies All graduates of NOBTS are expected to have at least a minimum level of competency in each of the following areas: Biblical Exposition, Christian Theological Heritage, Disciple Making, Interpersonal Skills, Servant Leadership, Spiritual and Character Formation, and Worship Leadership. -

Rhizome Updates from the Institute for the Study of Global Anabaptism

Rhizome Updates from the Institute for the Study of Global Anabaptism VOLUME 7, NUMBER 2 OCTOBER 2020 ISGA Publishes History of the Muria Javanese Mennonite Church in Indonesia Sigit Heru Sukoco Lawrence Yoder An upcoming book published translation by Lawrence M. their own cultural frame of by the ISGA, The Way of the Yoder, with extensive editing reference. Over the course of Gospel in the World of Java: A by ISGA director, John D. its long history, the developing History of the Muria Javanese Roth. communities of Christians Mennonite Church (GITJ), tells joined to form a community The Way of the Gospel in the the story of one branch of known as Gereja Injili di World of Java gives an account the Anabaptist-Mennonite Tanah Jawa (GITJ), or the Mu- of how missionaries of the INSIDE THIS churches in Indonesia. Au- ria Javanese Mennonite Dutch Mennonite Mission, ISSUE: thors Sigit Heru Sukoco and Church. along with indigenous Java- Lawrence M. Yoder originally Research Sym- 1 nese evangelists, sought to One of the indigenous found- posium wrote and published this his- evangelize the people of the ers of the Christian move- Project Updates 2 tory of the Muria Javanese Muria region of north Central ment in the Muria area was a Mennonite Church—known Visiting Scholar 2 Java starting in the 1850s. Javanese mystic, who took the in Indonesia as Gereja Injili di GAMEO 3 While European missionaries name Ibrahim Tunggul Tanah Jawa (GITJ)—in 2010 Editorial 4 functioned out of a western Wulung. This portrait, com- with the title Tata Injil di Bumi cultural framework, the Java- missioned by Lawrence Yoder, Muria.