The Correspondence Between Wycliffe, Hus and the Early Quakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Reviews Religious Syncretism and Deviance in Islamic And

Turkish Historical Review 3 (2012) 91–113 brill.nl/thr Book Reviews Religious syncretism and deviance in Islamic and Christian orthodoxies Angeliki Konstantakopoulou * Gilles Veinstein (ed.), Syncrétisme religieux et déviances de l’Orthodoxie chré- tienne et islamique. Syncrétismes et hérésies dans l’Orient Seldjoukide et Ottoman (XIVe-XVIIIe siècle), Actes du Colloque du Collège de France, Octobre 2001 (Paris: Peeters, 2005) (Collection Turcica, vol. 9), pp. 428, ISBN 904 2 915 49 8. Various aspects of the question of religious syncretism in the Middle East have repeatedly been the subject of research. Seen from an ‘orientalist’ and idealistic point of view, this question has been dealt with by national historiographies in a predictably justifi catory fashion. Moreover, after the end of the Cold War era, it resurfaced, integrated into wider questions such as that of the politicisa- tion of religion or that of the emergence of “ethnic-identities”, an issue which has recently engulfed the institutions of the European Union. In the current enfl amed situation, the historian has diffi culty in detaching himself/herself from the crucial present debate on religion/culture and confl icts (dictated as an almost exclusive approach and topic of research according to the lines of the ‘clash of civilizations’ theory). Often encountering retrospective and anachronistic interpretations, (s)he needs to revisit, among other issues, the question of the religious orthodoxies and of the deviances from them. Th e collective work presented here is, in short, an attempt to explore respective phenomena in their own historical terms. Th e participants at the Colloque of the Collège de France in October 2001 developed new analyses and proposed responses to an historical phenomenon which is linked in various ways to cur- rent political-ideological events (Preface by Gilles Veinstein, pp xiii-xiv). -

Importance of the Reformation

Do you have a Bible in the English language in your home? Did you know that it was once illegal to own a Bible in the common language? Please take a few minutes to read this very, very brief history of Christianity. Most modern-day Christians do not know our history—but we should! The New Testament church was founded by Jesus Christ, but it has faced opposition throughout its history. In the 50 years following the death and resurrection of Jesus, most of His 12 apostles were killed for preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ. The Roman government hated Christians because they wouldn’t bow down to their false gods or to Caesar and continued to persecute and kill Christians, such as Polycarp who they martyred in 155 AD. Widespread persecution and killing of Christians continued until 313 AD, when the emperor Constantine declared Christianity to be legal. His proclamation caused most of the persecution to stop, but it also had a side effect—the church and state began to rule the people together, effectively giving birth to the Roman Catholic Church. Over time, the Roman Catholic Church gained more and more power—but unfortunately, they became corrupted by that power. They gradually began to add things to the teachings found in the Bible. For example, they began to sell indulgences to supposedly help people spend less time in purgatory. However, the idea of purgatory is not found in the Bible, and the idea that money can improve one’s favor with God shows a complete lack of understanding of the truth preached by Jesus Christ. -

The Mayor and Early Lollard Dissemination

University of Central Florida STARS HIM 1990-2015 2012 The mayor and early Lollard dissemination Angel Gomez University of Central Florida Part of the Medieval History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015 University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIM 1990-2015 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Gomez, Angel, "The mayor and early Lollard dissemination" (2012). HIM 1990-2015. 1774. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/1774 THE MAYOR AND EARLY LOLLARD DISSEMINATION by ANGEL GOMEZ A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in History in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 Thesis Chair: Dr. Emily Graham Abstract During the fourteenth century in England there began a movement referred to as Lollardy. Throughout history, Lollardy has been viewed as a precursor to the Protestant Reformation. There has been a long ongoing debate among scholars trying to identify the extent of Lollard beliefs among the English. Attempting to identify who was a Lollard has often led historians to look at the trial records of those accused of being Lollards. One aspect overlooked in these studies is the role civic authorities, like the mayor of a town, played in the heresy trials of suspected Lollards. -

The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy

The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy: Through the Eyes Adam Giancola of the Waldensian Experience The Failure of the Protestant Reformation in Italy: Through the Eyes of the Waldensian Experience Adam Giancola In the wake of the Protestant Reformation, the experience of many countries across Europe was the complete overturning of traditional institutions, whereby religious dissidence became a widespread phenomenon. Yet the focus on Reformation history has rarely been given to countries like Italy, where a strong Catholic presence continued to persist throughout the sixteenth century. In this regard, it is necessary to draw attention to the ‘Italian Reformation’ and to determine whether or not the ideas of the Reformation in Western Europe had any effect on the religious and political landscape of the Italian peninsula. In extension, there is also the task to understand why the Reformation did not ‘succeed’ in Italy in contrast to the great achievements it made throughout most other parts of Western Europe. In order for these questions to be addressed, it is necessary to narrow the discussion to a particular ‘Protestant’ movement in Italy, that being the Waldensians. In an attempt to provide a general thesis for the ‘failure’ of the Protestant movement throughout Italy, a particular look will be taken at the Waldensian case, first by examining its historical origins as a minority movement pre-dating the European Reformation, then by clarifying the Waldensian experience under the sixteenth century Italian Inquisition, and finally, by highlighting the influence of the Counter-Reformation as pivotal for the future of Waldensian survival. Perhaps one of the reasons why the Waldensian experience differed so greatly from mainstream European reactions has to do with its historical development, since in many cases it pre-dated the rapid changes of the sixteenth century. -

Forerunners to the Reformation

{ Lecture 19 } FORERUNNERS TO THE REFORMATION * * * * * Long before Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the Wittenberg Door, there were those who recognized the corruption within the Roman Catholic Church and the need for major reform. Generally speaking, these men attempted to stay within the Catholic system rather than attempting to leave the church (as the Protestant Reformers later would do). The Waldensians (1184–1500s) • Waldo (or Peter Waldo) lived from around 1140 to 1218. He was a merchant from Lyon. But after being influenced by the story of the fourth-century Alexius (a Christian who sold all of his belongings in devotion to Christ), Waldo sold his belongings and began a life of radical service to Christ. • By 1170, Waldo had surrounded himself with a group of followers known as the Poor Men of Lyon, though they would later become known as Waldensians. • The movement was denied official sanction by the Roman Catholic Church (and condemned at the Third Lateran Council in 1179). Waldo was excommunicated by Pope Lucius III in 1184, and the movement was again condemned at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. • Waldensians were, therefore, persecuted by the Roman Catholics as heretics. However, the movement survived (even down to the present) though the Waldensians were often forced into hiding in the Alps. • The Waldensian movement was characterized by (1) voluntary poverty (though Waldo taught that salvation was not restricted to those who gave up their wealth), (2) lay preaching, and (2) the authority of the Bible (translated in the language of the people) over any other authority. -

Wyclif and Lollardy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department Classics and Religious Studies 2001 Wyclif and Lollardy Stephen E. Lahey University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub Part of the Classics Commons Lahey, Stephen E., "Wyclif and Lollardy" (2001). Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department. 82. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/82 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in The Medieval Theologians, edited by G. R. Evans (Blackwell, 2001), pp. 334-354. Copyright © 2001 Blackwell Publishers. Used by permission. Wyclif and Lollardy Stephen Lahey John Wyclif’s place in the history of Christian ideas varies according to the historian’s interest. As scholastic theology, Wyclif’s thought appears an heretical epilogue to the glories of the systematic innovations of the thirteenth century. Historians of the Prot- estantism, on the other hand, characterize him as a pioneer, the “Morning Star of the Reformation,” acknowledging -

Heretical Networks Between East and West: the Case of the Fraticelli

Heretical Networks between East and West: The Case of the Fraticelli NICKIPHOROS I. TSOUGARAKIS Abstract: This article explores the links between the Franciscan heresy of the Fraticelli and the Latin territories of Greece, between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries. It argues that the early involvement of Franciscan dissidents, like Angelo Clareno, with the lands of Latin Romania played an important role in the development of the Franciscan movement of dissent, on the one hand by allowing its enemies to associate them with the disobedient Greek Church and on the other by establishing safe havens where the dissidents were relatively safe from the persecution of the Inquisition and whence they were also able to send missionaries back to Italy to revive the movement there. In doing so, the article reviews all the known information about Fraticelli communities in Greece, and discovers two hitherto unknown references, proving that the sect continued to exist in Greece during the Ottoman period, thus outlasting the Fraticelli communities of Italy. Keywords: Fraticelli; Franciscan Spirituals; Angelo Clareno; heresy; Latin Romania; Venetian Crete. 1 Heretical Networks between East and West: The Case of the Fraticelli The flow of heretical ideas between Byzantium and the West is well-documented ever since the early Christian centuries and the Arian controversy. The renewed threat of popular heresy in the High Middle Ages may also have been influenced by the East, though it was equally fuelled by developments in western thought. The extent -

The Impact of Pilgrimage Upon the Faith and Faith-Based Practice of Catholic Educators

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators Rachel Capets The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Capets, R. (2018). The impact of pilgrimage upon the faith and faith-based practice of Catholic educators (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Education)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/219 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE FAITH AND FAITH-BASED PRACTICE OF CATHOLIC EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy, Education The University of Notre Dame, Australia Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P. 23 August 2018 THE IMPACT OF PILGRIMAGE UPON THE CATHOLIC EDUCATOR Declaration of Authorship I, Sister Mary Rachel Capets, O.P., declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Education, University of Notre Dame Australia, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. -

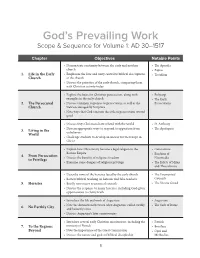

Scope & Sequence

God’s Prevailing Work Scope & Sequence for Volume 1: AD 30–1517 Chapter Objectives Notable Points • Demonstrate continuity between the early and modern • The Apostles church • Papias 1. Life in the Early • Emphasize the love and unity central to biblical descriptions • Tertullian Church of the church • Discuss the priorities of the early church, comparing them with Christian activity today • Explore the basis for Christian persecution, along with • Polycarp examples in the early church • The Early 2. The Persecuted • Discuss common responses to persecution, as well as the Persecutions Church view encouraged by Scripture • Note ways that God can turn the evils of persecution toward good • Discuss ways Christians have related with the world • St. Anthony • Discern appropriate ways to respond to opposition from • The Apologists 3. Living in the unbelievers World • Challenge students to develop an answer for their hope in Christ • Explain how Christianity became a legal religion in the • Constantine Roman Empire • Eusebius of 4. From Persecution • Discuss the benefits of religious freedom Nicomedia to Privilege • Examine some dangers of religious privilege • The Edicts of Milan and Thessalonica • Describe some of the heresies faced by the early church • The Ecumenical • Review biblical teaching on heresies and false teachers Councils 5. Heresies • Briefly note major ecumenical councils • The Nicene Creed • Discuss the response to major heresies, including God-given opportunities to clarify truth • Introduce the life and work of Augustine • Augustine • Note the distinctions between what Augustine called earthly • The Sack of Rome 6. No Earthly City and heavenly cities • Discuss Augustine’s later controversies • Introduce several early Christian missionaries, including the • Patrick 7. -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

Bridging Worlds: Buddhist Women's Voices Across Generations

BRIDGING WORLDS Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo First Edition: Yuan Chuan Press 2004 Second Edition: Sakyadhita 2018 Copyright © 2018 Karma Lekshe Tsomo All rights reserved No part of this book may not be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage or retreival system, without the prior written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations. Cover Illustration, "Woman on Bridge" © 1982 Shig Hiu Wan. All rights reserved. "Buddha" calligraphy ©1978 Il Ta Sunim. All rights reserved. Chapter Illustrations © 2012 Dr. Helen H. Hu. All rights reserved. Book design and layout by Lillian Barnes Bridging Worlds Buddhist Women’s Voices Across Generations EDITED BY Karma Lekshe Tsomo 7th Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women With a Message from His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama SAKYADHITA | HONOLULU, HAWAI‘I iv | Bridging Worlds Contents | v CONTENTS MESSAGE His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii INTRODUCTION 1 Karma Lekshe Tsomo UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN AROUND THE WORLD Thus Have I Heard: The Emerging Female Voice in Buddhism Tenzin Palmo 21 Sakyadhita: Empowering the Daughters of the Buddha Thea Mohr 27 Buddhist Women of Bhutan Tenzin Dadon (Sonam Wangmo) 43 Buddhist Laywomen of Nepal Nivedita Kumari Mishra 45 Himalayan Buddhist Nuns Pacha Lobzang Chhodon 59 Great Women Practitioners of Buddhadharma: Inspiration in Modern Times Sherab Sangmo 63 Buddhist Nuns of Vietnam Thich Nu Dien Van Hue 67 A Survey of the Bhikkhunī Saṅgha in Vietnam Thich Nu Dong Anh (Nguyen Thi Kim Loan) 71 Nuns of the Mendicant Tradition in Vietnam Thich Nu Tri Lien (Nguyen Thi Tuyet) 77 vi | Bridging Worlds UNDERSTANDING BUDDHIST WOMEN OF TAIWAN Buddhist Women in Taiwan Chuandao Shih 85 A Perspective on Buddhist Women in Taiwan Yikong Shi 91 The Inspiration ofVen. -

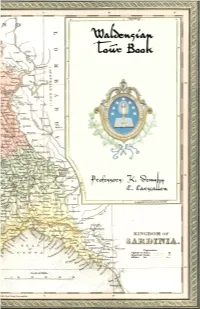

Waldensian Tour Guide

1 ii LUX LUCET EN TENEBRIS The words surrounding the lighted candle symbolize Christ’s message in Matthew 5:16, “Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your father who is in heaven.” The dark blue background represents the night sky and the spiritual dark- ness of the world. The seven gold stars represent the seven churches mentioned in the book of Revelation and suggest the apostolic origin of the Waldensian church. One oak tree branch and one laurel tree branch are tied together with a light blue ribbon to symbolize strength, hope, and the glory of God. The laurel wreath is “The Church Triumphant.” iii Fifth Edition: Copyright © 2017 Original Content: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout Redesign:Luis Rios First Edition Copyright © 2011 Published by: School or Architecture Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI 49104 Compiled and written: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout and Design: Kathleen Demsky & David Otieno Credits: Concepts and ideas are derived from my extensive research on this history, having been adapted for this work. Special credit goes to “The Burning Bush” (Captain R. M. Stephens) and “Guide to the Trail of Faith” (Maxine McCall). Where there are direct quotes I have given credit. Web Sources: the information on the subjects of; Fortress Fenestrelle, Arch of Augustus, Fortress of Exhilles and La Reggia Veneria Reale ( Royal Palace of the Dukes of Savoy) have been adapted from GOOGLE searches. Please note that some years the venue will change. iv WALDENSIAN TOUR GUIDE Fifth EDITION BY KATHLEEN M. DEMSKY v Castelluzzo April 1655 Massacre and Surrounding Events, elevation 4450 ft The mighty Castelluzzo, Castle of Light, stands like a sentinel in the Waldensian Valleys, a sacred monument to the faith and sacrifice of a people who were willing to pay the ultimate price for their Lord and Savior.