The Active-Duty Officer Promotion and Command Selection Processes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PART V – Civil Posts in Defence Services

PART V – Civil Posts in Defence Services Authority competent to impose penalties and penalties which itmay impose (with reference to item numbers in Rule 11) Serial Description of service Appointing Authority Penalties Number Authority (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) 1. Group ‘B’ Posts : (A) (i) All Group ‘B’ Additional Additional Secretary All (Gazetted) posts other than Secretary those specified in item (B). Chief Administrative Officer (i) to (iv) (ii) All Group ‘B’ (Non- Chief Chief Administrative Officer All Gazetted) posts other than Administrative those specified in item (B). Officer (B) Posts in Lower formations under - (i) General Staff Branch Deputy Chief of Deputy Chief of Army Staff. All Army Staff _ Director of Military Intelligence, | Director of Military Training, | Director of Artillery, Signals Officer-in-Chief, |(i) to (iv) Director of Staff Duties, as the case may be | | (ii) Adjutant-General’s Branch Adjutant-General Adjutant-General All Director of Organisation, Director of Medical (i) to (iv) Services, Judge Advocate-General, Director of Recruiting, Military and Air Attache, as the case may be. (iii) Quarter-Master-General’s Quarter-Master- Quarter-Master-General All Branch General Director concerned holding rank not below (i) to (iv) brigadier (iv) Master General of Master General Master-General of Ordnance All Ordnance Branch of ordnance Director of Ordinance Services, Director of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering, as the case may be (v) Engineer-in-Chief Branch Engineer in Chief All Chief Engineers of Commands (i) to -

B-177516 Enlisted Aide Program of the Military Services

I1111 lllllIIIlllll lllll lllll lllllIll11 Ill1 Ill1 LM096396 B-177576 Department of Defense BY THE C OF THE COMPTROLLER GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON, D.C. 200548 B-177516 To the President of the Senate and the c Speaker of the House of Representatives This is our report on the enlisted aide program of the \ military services, Department of Defense. C‘ / We made our review pursuant to the Budget and Accounting Act, 1921 (31 U.S.C. 53), and the Accounting and Auditing Act of 1950 (31 U.S.C. 67). We are sending copies of this report to the Director, Office of Management and Budget; the Secretary of Defense; the Secretar- ies of the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force; and the Commandant of the Marine Corps. Comptroller General of the United States Contents Page DIGEST 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 5 2 HISTORICAL AND LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND OF THE ENLISTED AIDE PROGRAM 8 Army and Air Force 8 Navy and Marine Corps 9 Legal aspects of using enlisted aides as servants 10 Summary 10 3 RECRUITMENT, ASSIGNMENT, AND TRAINING OF ENLISTED AIDES 12 Recruitment and assignment 12 Army training 13 Marine Corps training 15 Navy and Air Force training 15 4 MILITARY SERVICES' POSITIONS ON THE NEED FOR ENLISTED AIDES 16 Statements of the services regarding need for enlisted aides 16 Required hosting of official functions 18 Enlisted aides assigned by officer's rank 19 5 DUTIES AND TASKS OF ENLISTED AIDES 20 \ Major duties and tasks 20 Duties connected with entertaining 22 Feelings of enlisted aides about the the tasks assigned them 23 6 ENLISTED AIDES' -

28 Subpart H—The Commanding Officer

§ 700.720 32 CFR Ch. VI (7–1–13 Edition) or chief staff officer while he or she is Personnel, as appropriate, of such ac- executing the duties of that office. tion. (b) The officers of a staff shall be re- (b) If the designating commander de- sponsible for the performance of those sires the commanding officer of staff duties assigned to them by the com- enlisted personnel to possess authority mander and shall advise the com- to convene courts-martial, the com- mander on all matters pertaining mander should request the Judge Advo- thereto. In the performance of their cate General to obtain such authoriza- staff duties they shall have no com- tion from the Secretary of the Navy. mand authority of their own. In car- rying out such duties, they shall act § 700.723 Administration and dis- for, and in the name of, the com- cipline: Separate and detached mander. command. Any flag or general officer in com- ADMINISTRATION AND DISCIPLINE mand, any officer authorized to con- vene general courts-martial, or the § 700.720 Administration and dis- senior officer present may designate cipline: Staff embarked. organizations which are separate or de- In matters of general discipline, the tached commands. Such officer shall staff of a commander embarked and all state in writing that it is a separate or enlisted persons serving with the staff detached command and shall inform shall be subject to the internal regula- the Judge Advocate General of the ac- tions and routine of the ship. They tion taken. If authority to convene shall be assigned regular stations for courts-martial is desired for the com- battle and emergencies. -

Commodore John Barry

Commodore John Barry Day, 13th September Commodore John Barry (1745-1803) a native of County Wexford, Ireland was a Continental Navy hero of the American War for Independence. Barry’s many victories at sea during the Revolution were important to the morale of the Patriots as well as to the successful prosecution of the War. When the First Congress, acting under the new Constitution of the United States, authorized the raising and construction of the United States Navy, President George Washington turned to Barry to build and lead the nation’s new US Navy, the successor to the Continental Navy. On 22 February 1797, President Washington conferred upon Barry, with the advice and consent of the Senate, the rank of Captain with “Commission No. 1,” United States Navy, effective 7 June 1794. Barry supervised the construction of his own flagship, the USS UNITED STATES. As commander of the first United States naval squadron under the Constitution, which included the USS CONSTITUTION (“Old Ironsides”), Barry was a Commodore with the right to fly a broad pennant, which made him a flag officer. Commodore John Barry By Gilbert Stuart (1801) John Barry served as the senior officer of the United States Navy, with the title of “Commodore” (in official correspondence) under Presidents George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The ships built by Barry, and the captains selected, as well as the officers trained, by him, constituted the United States Navy that performed outstanding service in the “Quasi-War” with France, in battles with the Barbary Pirates and in America’s Second War for Independence (the War of 1812). -

Developing Senior Navy Leaders: Requirements for Flag Officer

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION the RAND Corporation. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Developing Senior Navy Leaders Requirements for Flag Officer Expertise Today and in the Future Lawrence M. -

RAND Study of Reserve Xxii Realigning the Stars

Realigning the Stars A Methodology for Reviewing Active Component General and Flag Officer Requirements RAND National Defense Research Institute C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2384 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0070-3 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2018 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover design by Eileen Delson La Russo; image by almagami/Getty Images. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Realigning the Stars Study Team Principal Investigator Lisa M. Harrington Structure and Organization Position-by-Position Position Pyramid Health Analysis Analysis Analysis Igor Mikolic-Torreira, Paul Mayberry, team lead Katharina Ley Best, team lead Sean Mann team lead Kimberly Jackson Joslyn Fleming Peter Schirmer Lisa Davis Alexander D. -

Charles Henry Davis. Is 07-18 77

MEMO I R CHARLES HENRY DAVIS. IS 07-18 77. C. H. DAVIS. RKAD ISEFORE rirrc NATFONAF, ACADK.MY, Ai'itn,, 1S()(>. -1 BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF CHARLES HENRY DAVIS. CHARLES HENRY DAVIS was born in Boston, January 10, 1807. He was the youngest son of Daniel Davis, Solicitor General of the State of Massachusetts. Of the other sons, only one reached maturity, Frederick Hersey Davis, who died in Louisiana about 1840, without issue. The oldest daughter, Louisa, married William Minot, of Boston. Daniel Davis was the youngest son of Hon. Daniel Davis, of Barnstablc, justice of the Crown and judge of probate and com- mon pleas for the county of Barn.stable. The family had been settled in Barnstable since 1038. Daniel Davis, the second, studied law, settled first in Portland (then Fahnouth), in the province of Maine, and moved to Boston in 1805. He married Lois Freeman, daughter of Captain Constant Freeman, also of Cape Cod. Her brother. Iiev. James Freeman, was for forty years rector of the King's Chapel in Boston, and was the first Unita- rian minister in Massachusetts. The ritual of King's Chapel was changed to conform to the modified views of the rector, and remains the same to this day. Another brother, Colonel Constant Freeman, served through the Revolutionary war and attained the rank of lieutenant colonel of artillery. In 1802 lie was on the permanent establishment as lieutenant colonel of the First United States Artillery. After the war of 1812-'14 be resigned and was Fourth Auditor of tlie Treasury until bis death, in 1824. -

I Drape-Nuts Son, Lottie Esplna Johnson

that we mast bare more officer* and better trained men of high rank. In all the prin¬ EISEMAN & CO.. 421 7TH, § cipal navies of the world except our own Under Odd Fellows' Hall. St admiral forms of the GRADUATE TOGETHER WHATTHE NAVY LACKS the grade of vlc«> part regular organisation. Other nations have apparently created that grade to give a AN OPEN strong Inducement to rear admirals t« be V- Pro¬ industrious and to develop their skill and Colored Nomal, and Admiral Dewey Discusses efficiency in a fair competition, for promo¬ High CONFESSJON. I tion for vice admiral; second, because the . § commander-in-chief Of a fleet or a large Schools. We're overstocked and will posed Retirement Scheme. squadron, with Increased authority and re¬ Armstrong resort to the most effective sponsibility, Is logically entitled to a higher rank than the flag officers serving under means of remedying that him; and, third. It gives a grade of select¬ state of affairs.in other OLD ed flag officers of high rank, experience, EXERCISES LAST EVENING FLAG OFFICERS TOO proved skill and efficiency, competent and words, SACRIFICE goods. ready to obtain the best possible results SPRING AND SUMMER with any fleet or squadron placed under his command. Audienoe in Convention Hail SUITS must go regardless High Rank Beached at an Earlier Age "The United 8tates has a smaller number Ap~ of value or of cost. of commissioned officers of all ranks In the in Other Countries. sea-going corps than any power except plauds Students. Take advantage of your Austria. We have only 1.95 commissioned to weara¬ officers to each 1,000 tons of warships chance provide built and building, while Great Britain bles at these ridiculous CHANCE FOE THE YOUNG MEN has 2.52. -

The Queen's Regulations for the Royal Air Force Fifth Edition 1999

UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED The Queen’s Regulations for the Royal Air Force Fifth Edition 1999 Amendment List No 30 QR(RAF AL30/Jun 12 UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED INTENTIONALLY BLANK QR(RAF AL30/Jun 12 UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED Contents CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................................................................1-1 CHAPTER 2 STRUCTURE OF THE SERVICES AND ORGANIZATION OF THE ROYAL AIR FORCE...........................................................2-1 CHAPTER 3 GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS FOR OFFICERS.......................................................................................................................................3-1 SECTION 1 - INSTRUCTIONS FOR COMMANDERS.................................................................................................................3-1 SECTION 2 - INSTRUCTIONS FOR OFFICERS GENERALLY...............................................................................................3-17 SECTION 3 - INSTRUCTIONS RELATING TO PARTICULAR BRANCHES OF THE SERVICE.....................................3-18 CHAPTER 4 COMMAND, CORRESPONDING RANK AND PRECEDENCE..........................................................................................................4-1 CHAPTER 5 CEREMONIAL............................................................................................................................................................................................5-1 -

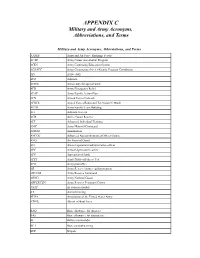

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

THE University of Memphis Naval ROTC MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE

THE University of Memphis Naval ROTC MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE Handbook 2014 (This page intentionally left blank) 1 May 2014 From: Commanding Officer, Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps, Mid-South Region, The University of Memphis To: Incoming Midshipmen Subj: MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE HANDBOOK Ref: (a) NSTC M-1533.2 1. PURPOSE: The purpose of this handbook is to provide a funda- mental background of knowledge for all participants in the Naval ROTC program at The University of Memphis. 2. INFORMATION: All chapters in this book contain vital, but basic information that will serve as the building blocks for future development as Naval and Marine Corps Officers. 3. ACTIONS: Midshipmen, Officer Candidates, and Marine Enlisted Commissioning Education Program participants are expected to know and understand all information contained within this handbook. Navy students will know the Marine information, and Marine students will know the Navy information. This will help to foster a sense of pride and esprit de corps that shapes the common bond that is shared amongst the two Naval Services. B. C. MAI (This page intentionally left blank) MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE HANDBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE 1 INTRODUCTION 2 CHAIN OF COMMAND 3 LEADERSHIP 4 GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 5 NAVY SPECIFIC KNOWLEDGE 6 MARINE CORPS SPECIFIC KNOWLEDGE APPENDIX A CHAIN OF COMMAND FILL-IN SHEET B STUDENT COMPANY CHAIN OF COMMAND FILL-IN SHEET C UNITED STATES MILITARY OFFICER RANKS D UNITED STATES MILITARY ENLISTED RANKS FIGURES 2-1 CHAIN OF COMMAND FLOW CHART 2-2 STUDENT COMPANY CHAIN OF COMMAND FLOW CHART 4-1 NAVAL TERMINOLOGY (This page intentionally left blank) MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE HANDBOOK CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION PARAGRAPH PAGE PURPOSE 1001 1-3 SCOPE 1002 1-3 GUIDELINES 1003 1-3 NROTC PROGRAM MISSION 1004 1-3 1-1 (This page intentionally left blank) MIDSHIPMEN KNOWLEDGE HANDBOOK 1001: PURPOSE 1. -

Flight of the Goeben

THE FLIGHT O F THE ‘ GOEBEN ’ AND THE ‘ B RESLAU ’ The ‘ ’ Flight o f the G oeben ‘ ’ and the B r eslau An Episode i n Naval BY S A B RK LEY M LN B DMI RAL m . r . A E E I E, ma n. LONDON EVELEIGH NASH CO MPANY LIMITED PREFACE F TE R u a 1920 of A the p blic tion in March , , “ the Official History of the War ' Nav al I u . Operations, Vol . by Sir J lian S I Corbett, represented to the First Lord of the Admiral ty that the book contained u u serio s inacc racies , and made a formal request that the Admiralty should take action in the matter . As the Admiralty did not think proper to accede to my u I u u s req est, have tho ght it right to p bli h f the ollowing narrative . ERKE LE Y I LNE . A . B M Admi ral . Jan uary 1921 . CONT ENT S PREFACE I . OFFI CI AL RESPONSIB IL ITY I I . THE SITU ATION IN JU LY 1914 PRELIMINARY DISPOSITIONS THE FRENCH DISPOSITIONS FI M G W V . RST EETIN ITH GOEB EN NE W DISPOSITIONS “ ” THE OFF ICIAL VERSION GOEB EN AND B RESLA U AT MESSINA SECOND MEETING WITH GOEB EN AND FURTHER D IS POS ITIONS XI . THE MIS TAKEN TELEGRAM THE S EARCH RES UMED THE ES CAPE L XI V . THE S E'UE XV . CONCLUS ION OFFICIAL RESP ONS IBILITY I OFF ICI AL RE S P ONS IB ILITY u u ffi I N j stice to the p blic, to the O cers r u and men who se ved nder my command , own u I u and to my rep tation, have tho ght it right to publish the following narrative Of the events in the Mediterranean imme diat ely preceding and following upon the u W o tbreak Of war, concerning hich there u u has been, and is , some nfort nate mis apprehension .