Charles Henry Davis. Is 07-18 77

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser

ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 May 2019: Admiral Sir Timothy P. Fraser: Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, May 2019 June 2019: Admiral Sir Antony D. Radakin: First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff, June 2019 (11/1965; 55) VICE-ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 February 2016: Vice-Admiral Sir Benjamin J. Key: Chief of Joint Operations, April 2019 (11/1965; 55) July 2018: Vice-Admiral Paul M. Bennett: to retire (8/1964; 57) March 2019: Vice-Admiral Jeremy P. Kyd: Fleet Commander, March 2019 (1967; 53) April 2019: Vice-Admiral Nicholas W. Hine: Second Sea Lord and Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff, April 2019 (2/1966; 55) Vice-Admiral Christopher R.S. Gardner: Chief of Materiel (Ships), April 2019 (1962; 58) May 2019: Vice-Admiral Keith E. Blount: Commander, Maritime Command, N.A.T.O., May 2019 (6/1966; 55) September 2020: Vice-Admiral Richard C. Thompson: Director-General, Air, Defence Equipment and Support, September 2020 July 2021: Vice-Admiral Guy A. Robinson: Chief of Staff, Supreme Allied Command, Transformation, July 2021 REAR ADMIRALS: AUGUST 2021 July 2016: (Eng.)Rear-Admiral Timothy C. Hodgson: Director, Nuclear Technology, July 2021 (55) October 2017: Rear-Admiral Paul V. Halton: Director, Submarine Readiness, Submarine Delivery Agency, January 2020 (53) April 2018: Rear-Admiral James D. Morley: Deputy Commander, Naval Striking and Support Forces, NATO, April 2021 (1969; 51) July 2018: (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Keith A. Beckett: Director, Submarines Support and Chief, Strategic Systems Executive, Submarine Delivery Agency, 2018 (Eng.) Rear-Admiral Malcolm J. Toy: Director of Operations and Assurance and Chief Operating Officer, Defence Safety Authority, and Director (Technical), Military Aviation Authority, July 2018 (12/1964; 56) November 2018: (Logs.) Rear-Admiral Andrew M. -

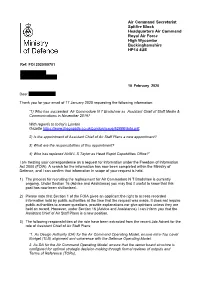

Information Regarding Who Has Succeeded Air Commodore N T

Air Command Secretariat i Spitfire Block Headquarters Air Command Royal Air Force High Wycombe Buckinghamshire HP14 4UE Ref: FOI 2020/00701 10 February 2020 Dear Thank you for your email of 17 January 2020 requesting the following information: “1) Who has succeeded Air Commodore N T Bradshaw as Assistant Chief of Staff Media & Communications in November 2019? With regards to today's London Gazette https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/62888/data.pdf, 2) Is the appointment of Assistant Chief of Air Staff Plans a new appointment? 3) What are the responsibilities of this appointment? 4) Who has replaced AVM L S Taylor as Head Rapid Capabilities Office?” I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA). A search for the information has now been completed within the Ministry of Defence, and I can confirm that information in scope of your request is held. 1) The process for recruiting the replacement for Air Commodore N T Bradshaw is currently ongoing. Under Section 16 (Advice and Assistance) you may find it useful to know that this post has now been civilianised. 2) Please note that Section 1 of the FOIA gives an applicant the right to access recorded information held by public authorities at the time that the request was made. It does not require public authorities to answer questions, provide explanations nor give opinions unless they are held on record. However, under Section 16 (Advice and Assistance) I can inform you that the Assistant Chief of Air Staff Plans is a new position. -

U.S.S. Sun-Tzu NX-1745

U.S.S. Sun-Tzu NX-1745 Member Handbook Updated 0718.19 Correspondence Chapter STARFLEET, The International Star Trek Fan Association U.S.S. Sun-Tzu NX-1745 Member Handbook Updated 0718.19 Dedicated to all those who we have lost in our exploration of the Final Frontier. LLAP 2 Contents 1.0)Disclaimer.……………………………………………………………..……………..….6 2.0)Welcome Aboard!………..………………….………………..……………………7 3.0)Ship History…………………………………..………………………………………….9 3.1)Specifications & Capacities…......…………………….……...…10 4.0)STARFLEET, The International FAN Association……………………………………...………………………...…………..14 5.0)Orginizational Structure…………………….………………….………...16 5.1)Correspondence Chapter Information……….………..18 5.2)Membership Information……………….….…………………..20 5.2.1)Cadet Membership……………………….………………22 5.2.2)Member ID………………..…………….…….……………….24 5.3)Command Structure……………..…………...…………………...24 5.3.1)Command Staff………………………..……………….…26 5.3.2)Chain of Command………………..…………………...27 5.4)Divisions…………………………………………………….………….….…..28 5.4.1)All Departments……………..…….……………………29 5.4.2)Command Division…………….……….…………………30 5.4.2.1)Command………………….……………….…..31 5.4.2.2)Cadet Corps………….….………………….34 3 5.4.2.3)Education………………………………..…….35 5.4.3)Operations Division…………………………..………...37 5.4.3.1)Communications………………..………..37 5.4.3.2)Engineering…………………………….……..38 5.4.3.3)Helm Control…………………..…………39 5.4.3.4)Security.………………………………..……...39 5.4.3.5)Tactical…………………………..…..……….40 5.4.3.6)Weapons……………………………..………...41 5.4.4)Sciences Division……………………..……………………..41 5.4.4.1)Medical…………….…………………………..42 5.4.5)Marines…………………...……………………………………….43 -

PART V – Civil Posts in Defence Services

PART V – Civil Posts in Defence Services Authority competent to impose penalties and penalties which itmay impose (with reference to item numbers in Rule 11) Serial Description of service Appointing Authority Penalties Number Authority (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) 1. Group ‘B’ Posts : (A) (i) All Group ‘B’ Additional Additional Secretary All (Gazetted) posts other than Secretary those specified in item (B). Chief Administrative Officer (i) to (iv) (ii) All Group ‘B’ (Non- Chief Chief Administrative Officer All Gazetted) posts other than Administrative those specified in item (B). Officer (B) Posts in Lower formations under - (i) General Staff Branch Deputy Chief of Deputy Chief of Army Staff. All Army Staff _ Director of Military Intelligence, | Director of Military Training, | Director of Artillery, Signals Officer-in-Chief, |(i) to (iv) Director of Staff Duties, as the case may be | | (ii) Adjutant-General’s Branch Adjutant-General Adjutant-General All Director of Organisation, Director of Medical (i) to (iv) Services, Judge Advocate-General, Director of Recruiting, Military and Air Attache, as the case may be. (iii) Quarter-Master-General’s Quarter-Master- Quarter-Master-General All Branch General Director concerned holding rank not below (i) to (iv) brigadier (iv) Master General of Master General Master-General of Ordnance All Ordnance Branch of ordnance Director of Ordinance Services, Director of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering, as the case may be (v) Engineer-in-Chief Branch Engineer in Chief All Chief Engineers of Commands (i) to -

B-177516 Enlisted Aide Program of the Military Services

I1111 lllllIIIlllll lllll lllll lllllIll11 Ill1 Ill1 LM096396 B-177576 Department of Defense BY THE C OF THE COMPTROLLER GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON, D.C. 200548 B-177516 To the President of the Senate and the c Speaker of the House of Representatives This is our report on the enlisted aide program of the \ military services, Department of Defense. C‘ / We made our review pursuant to the Budget and Accounting Act, 1921 (31 U.S.C. 53), and the Accounting and Auditing Act of 1950 (31 U.S.C. 67). We are sending copies of this report to the Director, Office of Management and Budget; the Secretary of Defense; the Secretar- ies of the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force; and the Commandant of the Marine Corps. Comptroller General of the United States Contents Page DIGEST 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 5 2 HISTORICAL AND LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND OF THE ENLISTED AIDE PROGRAM 8 Army and Air Force 8 Navy and Marine Corps 9 Legal aspects of using enlisted aides as servants 10 Summary 10 3 RECRUITMENT, ASSIGNMENT, AND TRAINING OF ENLISTED AIDES 12 Recruitment and assignment 12 Army training 13 Marine Corps training 15 Navy and Air Force training 15 4 MILITARY SERVICES' POSITIONS ON THE NEED FOR ENLISTED AIDES 16 Statements of the services regarding need for enlisted aides 16 Required hosting of official functions 18 Enlisted aides assigned by officer's rank 19 5 DUTIES AND TASKS OF ENLISTED AIDES 20 \ Major duties and tasks 20 Duties connected with entertaining 22 Feelings of enlisted aides about the the tasks assigned them 23 6 ENLISTED AIDES' -

Biographical Notices, and Records of Naval Officers

PRIVATE SIGNAL 666 PROJECTILES if his vessel of such sia, Sardinia, and Turkey united in a declaration was acting independently that " privateering is and remains abolished." superior officer. The United States, however, has never assented Fifth. After the foregoing deductions, the residue is distributed all others to this declaration, and as to it, therefore, priva among doing on the books of the teering remains legitimate. See INTERNATIONAL duty board, and borne upon 10 DECLARATION OF. the fleet-captain, in LAW, ; PARIS, ship, including proportion PRIVATEERSMAN. One of the crew of a priva to their respective rates of pay. teer. All vessels of the navy within signal-distance Private Signal. A signal intelligible only to of the vessel making the capture, and in such condition as to able to render effective aid if those having the key. be Prize. A captured vessel or other property required, will share in the prize. Any person taken in naval warfare. The right to all cap temporarily absent from his vessel may share in no his absence. tures vests primarily in the sovereign, and captures made during The prize- individual can have any interest in a capture court determines what vessels shall share in a vessel what he re and also whether the was of by a public or private except prize, prize superior, ceives under the grant of the state. See INTER equal, or inferior force to the vessel or vessels of NATIONAL LAW, 11. the captors. The Secretary of the Navy deter PRIZE-COURT. The court whose jurisdiction mines what persons are entitled to share in the includes the adjudication and disposition of prize-money awarded a vessel, and transmits 12. -

Air Chief Marshal Frank Robert MILLER, CC, CBE, CD Air Member

Air Chief Marshal Frank Robert MILLER, CC, CBE, CD Air Member Operations and Training (C139) Chief of the RCAF Post War Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff and First Chief of Staff 01 August 1964 - 14 July 1966 Born: 30 April 1908 Kamloops, British Columbia Married: 03 May 1938 Dorothy Virginia Minor in Galveston, Texas Died: 20 October 1997 Charlottesville, Virginia, USA (Age 89) Honours CF 23/12/1972 CC Companion of the Order of Canada Air Chief Marshal RCAF CG 13/06/1946 CBE Commander of the Order of the British Empire Air Vice-Marshal RCAF LG 14/06/1945+ OBE Officer of the Order of the British Empire Air Commodore RCAF LG 01/01/1945+ MID Mentioned in Despatches Air Commodore RCAF Education 1931 BSc University of Alberta (BSc in Civil Engineering) Military 01/10/1927 Officer Cadet Canadian Officer Training Corps (COTC) 15/09/1931 Pilot Officer Royal Canadian Air Force 15/10/1931 Pilot Officer Pilot Training at Camp Borden 16/12/1931 Flying Officer Receives his Wings 1932 Flying Officer Leaves RCAF due to budget cuts 07/1932 Flying Officer Returns to the RCAF 01/02/1933 Flying Officer Army Cooperation Course at Camp Borden in Avro 621 Tutor 31/05/1933 Flying Officer Completes Army Cooperation Course at Camp Borden 30/06/1933 Flying Officer Completes Instrument Flying Training on Gipsy Moth & Tiger Moth 01/07/1933 Flying Officer Seaplane Conversion Course at RCAF Rockcliffe Vickers Vedette 01/08/1933 Flying Officer Squadron Armament Officer’s Course at Camp Borden 22/12/1933 Flying Officer Completes above course – Flying the Fairchild 71 Courier & Siskin 01/01/1934 Flying Officer No. -

An Outstanding Ngs 1793 Awarded to a Officer Who

AN OUTSTANDING NGS 1793 AWARDED TO A OFFICER WHO AFTER SERVING AT HOTHAM’S ACTIONS IN 1795 AND THE BATTLE OF CAPE ST VINCENT in 1797, WAS PRESENT AS SIGNAL MIDSHIPMAN AND ADC ABOARD H.M.S. GOLIATH AT NELSON’s GREAT VICTORY AT THE BATTLE OF THE NILE, 1798. ARGUABLY THE MOST IMPORTANT SHIP AT THAT BATTLE. WOUNDED DURING THE LATTER, HE COMMANDED H.M.S. NAUTILUS 1808- 14, CAPTURING CAPTURED SIX PRIVATEERS, AND DESTROYED A SEVENTH. DURING HIS SERVICE HE WAS WOUNDED 6 TIMES NAVAL GENERAL SERVICE 1793, 3 CLASPS, 14 MARCH 1795, ST. VINCENT, NILE ‘THOMAS DENCH, MIDSHIPMAN.’ CAPTAIN THOMAS DENCH Thomas Dench was born circa 1778 and entered the Navy in April 1793, as Midshipman on board the Ardent (64), Captain Robert Manners Sutton. During his service with this ship he served on shore at the occupation of Toulon, and was in warm action with the batteries of St. Fiorenza during the siege of Corsica. In April 1794, when the Ardent took fire and blew up, with all hands on board, this officer had the good fortune to be absent in charge of a prize. Dench’s next appointment was as Midshipman aboard St. George (98), Captain Thomas Foley, this the flag-ship of Sir Hyde Parker. During his service, he took part in Admiral Hotham’s actions of 14 March and 13 July, 1795. At the former, which was also known as the the Battle of Genoa, the British-Neapolitan fleet claimed victory capturing 2 French ships. The ‘14 March 1795’ clasp to the Naval General Service Medal, was awarded for this action. -

The Active-Duty Officer Promotion and Command Selection Processes

Issue Paper #34 Promotion Version 3 The Active-Duty Officer Promotion and Command Selection Processes Considerations for Race/Ethnicity and Gender MLDC Research Areas 1 Definition of Diversity Abstract gender. The MLDC in turn requested that the military Services and the Coast Guard Legal Implications Two MLDC charter tasks directed the com- describe their promotion and command selec- Outreach & Recruiting missioners to evaluate whether the officer tion processes so that the MLDC could study promotion and command selection systems whether certain features of these systems Leadership & Training provide fair opportunities to both men and might affect the selection of officers based on Branching & Assignments women and members of all race/ethnicity their race/ethnicity or gender. A summary of groups. Using Service briefings and other the presentations from the fall 2009 and win- Promotion information provided to the MLDC, this ter 2010 MLDC meetings, along with relevant Retention Issue Paper (IP) describes key features of material provided by the Services after the meetings, is presented.2 Implementation & the promotion and command selection proc- Accountability esses and discusses how they may accentu- There are three main ways in which ate or mitigate the potential for bias in the promotion and command opportunities may Metrics selection of officers for promotion or com- be unfair. First, a lack of fairness may develop National Guard & Reserve mand. Overall, the promotion and command before officers are actually evaluated for selection board processes include a number promotion or command selection; this occurs of features that attempt to impart fairness if race/ethnicity or gender affects the assign- and to mitigate the impact of bias on the ment of officers to key positions that enhance part of an individual board member. -

The Legacy of Commodore David Porter, USN: Midshipman David Glasgow Farragut Part One of a Three-Part Series

The Legacy of Commodore David Porter, USN: Midshipman David Glasgow Farragut Part One of a three-part series Vice Admiral Jim Sagerholm, USN (Ret.), September 15, 2020 blueandgrayeducation.org David Glasgow Farragut | National Portrait Gallery In any discussion of naval leadership in the Civil War, two names dominate: David Glasgow Farragut and David Dixon Porter. Both were sons of David Porter, one of the U.S. Navy heroes in the War of 1812, Farragut having been adopted by Porter in 1808. Farragut’s father, George Farragut, a seasoned mariner from Spain, together with his Irish wife, Elizabeth, operated a ferry on the Holston River in eastern Tennessee. David Farragut was their second child, born in 1801. Two more children later, George moved the family to New Orleans where the Creole culture much better suited his Mediterranean temperament. Through the influence of his friend, Congressman William Claiborne, George Farragut was appointed a sailing master in the U.S. Navy, with orders to the naval station in New Orleans, effective March 2, 1807. George Farragut | National Museum of American David Porter | U.S. Naval Academy Museum History The elder Farragut traveled to New Orleans by horseback, but his wife and four children had to go by flatboat with the family belongings, a long and tortuous trip lasting several months. A year later, Mrs. Farragut died from yellow fever, leaving George with five young children to care for. The newly arrived station commanding officer, Commander David Porter, out of sympathy for Farragut, offered to adopt one of the children. The elder Farragut looked to the children to decide which would leave, and seven-year-old David, impressed by Porter’s uniform, volunteered to go. -

Commodore John Barry

Commodore John Barry Day, 13th September Commodore John Barry (1745-1803) a native of County Wexford, Ireland was a Continental Navy hero of the American War for Independence. Barry’s many victories at sea during the Revolution were important to the morale of the Patriots as well as to the successful prosecution of the War. When the First Congress, acting under the new Constitution of the United States, authorized the raising and construction of the United States Navy, President George Washington turned to Barry to build and lead the nation’s new US Navy, the successor to the Continental Navy. On 22 February 1797, President Washington conferred upon Barry, with the advice and consent of the Senate, the rank of Captain with “Commission No. 1,” United States Navy, effective 7 June 1794. Barry supervised the construction of his own flagship, the USS UNITED STATES. As commander of the first United States naval squadron under the Constitution, which included the USS CONSTITUTION (“Old Ironsides”), Barry was a Commodore with the right to fly a broad pennant, which made him a flag officer. Commodore John Barry By Gilbert Stuart (1801) John Barry served as the senior officer of the United States Navy, with the title of “Commodore” (in official correspondence) under Presidents George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The ships built by Barry, and the captains selected, as well as the officers trained, by him, constituted the United States Navy that performed outstanding service in the “Quasi-War” with France, in battles with the Barbary Pirates and in America’s Second War for Independence (the War of 1812). -

The Idea of a “Fleet in Being” in Historical Perspective

Naval War College Review Volume 67 Article 6 Number 1 Winter 2014 The deI a of a “Fleet in Being” in Historical Perspective John B. Hattendorf Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Hattendorf, John B. (2014) "The deI a of a “Fleet in Being” in Historical Perspective," Naval War College Review: Vol. 67 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol67/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hattendorf: The Idea of a “Fleet in Being” in Historical Perspective THE IDEA OF a “FLEET IN BEING” IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE John B. Hattendorf he phrase “fleet in being” is one of those troublesome terms that naval his- torians and strategists have tended to use in a range of different meanings. TThe term first appeared in reference to the naval battle off Beachy Head in 1690, during the Nine Years’ War, as part of an excuse that Admiral Arthur Herbert, first Earl of Torrington, used to explain his reluctance to engage the French fleet in that battle. A later commentator pointed out that the thinking of several Brit- ish naval officers ninety years later during the War for American Independence, when the Royal Navy was in a similar situation of inferior strength, contributed an expansion to the fleet-in-being concept.