Masculinities, Planning Knowledge and Domestic Space in Britain, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unlve.Noil'r of GREENWICH This Mphil Thesis Is Submitted in Partial

UNIVERSITY OF GREENWICH LIBRARY FOR REFERENCE USE ONLY INSTITUTIONAL CONTROL OF ARCHITECTURAL EDUCATION AND REGISTRATION 1834-1960 Ms H M Startup BA (Hons) I sro UNlVE.noil'r OF GREENWICH LIBRARY FOR REFERENCE USE ONLY This MPhil Thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for this degree. December 1984 ABSTRACT OF THESIS INSTITUTIONAL CONTROL OF ARCHITECTURAL EDUCATION AND REGISTRATION: A HISTORY OF THE ROLE OF ITS PROFESSIONAL AND STATUTORY BODIES 1834-1960 Henrietta Miranda Startup This thesis examines the history of architectural education and professionalism in Britain from the foundation of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) in 1834 to the Oxford Conference on education held by the RIBA in 1958. Between these dates, it investigates with primary source material drawn from the RIBA and the Architects Registration Council (ARCUK), the nature and development of these institutions in relation to one another in the evolution of an educational policy for the architectural profession. The scope of the work embraces an exploration both of the controls placed by the profession on education and of the statutory limits to professional control promulgated by the State. The thesis sets out, first, to analyse the links made between the formation of the RIBA and its search for an appropriate qualification and examination system which would regulate entry into the RIBA. It then considers the ways in which the RIBA sought to implement and rationalise this examination system in order to further educational opportunities for its members and restrict architectural practice. This is followed by an account of the means by which the profession began to achieve statutory recognition of its own knowledge and practice. -

From Victorian to Modernist

Title From Victorian to Modernist: the changing perceptions of Japanese architecture encapsulated in Wells Coates' Japonisme dovetailing East and West Type The sis URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/15643/ Dat e 2 0 0 7 Citation Basham, Anna Elizabeth (2007) From Victorian to Modernist: the changing perceptions of Japanese architecture encapsulated in Wells Coates' Japonisme dovetailing East and West. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Cr e a to rs Basham, Anna Elizabeth Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author From Victorian to Modernist: the changing perceptions of Japanese architecture encapsulated in Wells Coates' Japonisme dovetailing East and West Anna Elizabeth Basham Submitted as a partial requirement for the degree of doctor of philosophy, awarded by the University of the Arts London. Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) Chelsea College of Art and Design University of the Arts London April 2007 Volume 2 - appendices IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl,uk VOLUME 2 Appendix 1 ., '0 'J I<:'1'J ES, I N. 'TIT ')'LOi\fH, &c., 1'lCi't/'f (It I ,Jo I{ WAit'lL .\1. llli I'HO (; EELI1)i~ ;S ,'llId tilt Vol/IIII/' (!( 'l'1:AXSA rj(J~s IIf till' HO!/flt II} /"'t/ l., 11 . 1I'l l/ it l(' f .~. 1.0N"1J X . Sl 'o'n,"\ ~ I). -

Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events

November 2016 Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events Gilbert & George contemplate one of Raju's photographs at the launch of Brick Lane Born Our main exhibition, on show until 7 January is Brick Lane Born, a display of over forty photographs taken in the mid-1980s by Raju Vaidyanathan depicting his neighbourhood and friends in and around Brick Lane. After a feature on ITV London News, the exhibition launched with a bang on 20 October with over a hundred visitors including Gilbert and George (pictured), a lively discussion and an amazing joyous atmosphere. Comments in the Visitors Book so far read: "Fascinating and absorbing. Raju's words and pictures are brilliant. Thank you." "Excellent photos and a story very similar to that of Vivian Maier." "What a fascinating and very special exhibition. The sharpness and range of photographs is impressive and I am delighted to be here." "What a brilliant historical testimony to a Brick Lane no longer in existence. Beautiful." "Just caught this on TV last night and spent over an hour going through it. Excellent B&W photos." One launch attendee unexpectedly found a portrait of her late father in the exhibition and was overjoyed, not least because her children have never seen a photo of their grandfather during that period. Raju's photos and the wonderful stories told in his captions continue to evoke strong memories for people who remember the Spitalfields of the 1980s, as well as fascination in those who weren't there. An additional event has been added to the programme- see below for details. -

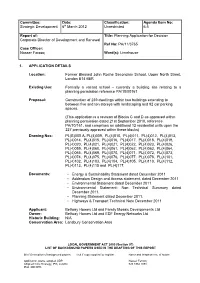

Strategic Development Date: 6Th March 2012 Classification

Committee: Date: Classification: Agenda Item No: Strategic Development 6th March 2012 Unrestricted 6.5 Report of: Title: Planning Application for Decision Corporate Director of Development and Renewal Ref No: PA/11/3765 Case Officer: Nasser Farooq Ward(s): Limehouse 1. APPLICATION DETAILS Location: Former Blessed John Roche Secondary School, Upper North Street, London E14 6ER Existing Use: Formally a vacant school – currently a building site relating to a planning permission reference PA/10/00161 Proposal: Construction of 239 dwellings within two buildings extending to between five and ten storeys with landscaping and 92 car parking spaces. (This application is a revision of Blocks C and D as approved within planning permission dated 21st September 2010, reference PA/10/161, and comprises an additional 12 residential units upon the 227 previously approved within these blocks) Drawing Nos: PL(B)005 A, PL(4)009, PL(4)010, PL(4)011, PL(4)012, PL(4)013, PL(4)014, PL(4)015, PL(4)016, PL(4)017, PL(4)018, PL(4)019, PL(4)020, PL(4)021, PL(4)021, PL(4)022, PL(4)023, PL(4)026, PL(4)059, PL(4)060, PL(4)061, PL(4)062, PL(4)063, PL(4)064, PL(4)065, PL(4)069, PL(4)070, PL(4)071, PL(4)072, PL(4)073, PL(4)074, PL(4)075, PL(4)076, PL(4)077, PL(4)078, PL(4)101, PL(4)102, PL(4)103, PL(4)104, PL(4)105, PL(4)110, PL(4)112, PL(4)113, PL(4)115 and PL(4)117. -

Who Is Council Housing For?

‘We thought it was Buckingham Palace’ ‘Homes for Heroes’ Cottage Estates Dover House Estate, Putney, LCC (1919) Cottage Estates Alfred and Ada Salter Wilson Grove Estate, Bermondsey Metropolitan Borough Council (1924) Tenements White City Estate, LCC (1938) Mixed Development Somerford Grove, Hackney Metropolitan Borough Council (1949) Neighbourhood Units The Lansbury Estate, Poplar, LCC (1951) Post-War Flats Spa Green Estate, Finsbury Metropolitan Borough Council (1949) Berthold Lubetkin Post-War Flats Churchill Gardens Estate, City of Westminster (1951) Architectural Wars Alton East, Roehampton, LCC (1951) Alton West, Roehampton, LCC (1953) Multi-Storey Housing Dawson’s Heights, Southwark Borough Council (1972) Kate Macintosh The Small Estate Chinbrook Estate, Lewisham, LCC (1965) Low-Rise, High Density Lambeth Borough Council Central Hill (1974) Cressingham Gardens (1978) Camden Borough Council Low-Rise, High Density Branch Hill Estate (1978) Alexandra Road Estate (1979) Whittington Estate (1981) Goldsmith Street, Norwich City Council (2018) Passivhaus Mixed Communities ‘The key to successful communities is a good mix of people: tenants, leaseholders and freeholders. The Pepys Estate was a monolithic concentration of public housing and it makes sense to break that up a bit and bring in a different mix of incomes and people with spending power.’ Pat Hayes, LB Lewisham, Director of Regeneration You have castrated communities. You have colonies of low income people, living in houses provided by the local authorities, and you have the higher income groups living in their own colonies. This segregation of the different income groups is a wholly evil thing, from a civilised point of view… We should try to introduce what was always the lovely feature of English and Welsh villages, where the doctor, the grocer, the butcher and the farm labourer all lived in the same street – the living tapestry of a mixed community. -

Seminar Week People Commonly

AN ADDENDUM TO LONDON’S NATURAL HISTORY by R.S.R. Fitter PEOPLE COMMONLY FOUND IN LONDON DEBTS OF GRATITUDE INTRODUCTION OVERVIEW MONDAY – WEST TUESDAY – NORTH WEDNESDAY – SOUTH THURSDAY – EAST FRIDAY – CENTRAL DIRECTORY SEMINAR WEEK 2 2 – 2 8 O C T O B E R STUDIO TOM EMERSON D-ARCH ETH ZURICH MMXVII 2 PEOPLE COMMONLY FOUND IN LONDON* Cyril Amrein +41 79 585 83 34; Céline Bessire +41 79 742 94 91; Lucio Crignola +41 78 858 54 02; Toja Coray +41 79 574 40 69; Vanessa Danuser +41 78 641 10 65; Nick Drofiak +41 75 417 31 95; Boris Gusic +41 79 287 43 60; David Eckert +41 79 574 40 71; Tom Emerson; Zaccaria Exhenry +41 79 265 02 90; Gabriel Fiette +41 78 862 62 64; Kathrin Füglister +41 79 384 12 73; Pascal Grumbacher +41 79 595 60 95; Jonas Heller +41 78 880 12 55; Joel Hösle +41 77 483 57 67; Jens Knöpfel +41 77 424 62 38; Shohei Kunisawa +41 78 704 43 79; Juliette Martin +41 78 818 88 34; Khalil Mdimagh +41 76 416 52 25; Colin Müller +41 79 688 06 08; Alice Müller +41 79 675 40 76; Philip Shelley +44 77 5178 05 81; Tobia Rapelli +41 79 646 37 18; Daria Ryffel +41 79 881 67 70; Florian von Planta +41 79 793 52 55; Andreas Winzeler +41 79 537 63 30; Eric Wuite +41 77 491 61 57; Tian Zhou +41 78 676 96 15 DEBTS OF GRATITUDE Many thanks to Taran Wilkhu & family, Kim Wilkie, Rebecca Law, Robert Youngs, Angela Kidner, Alex Sainsbury, Juergen Teller Studio, James Green, Adam Willis, Paloma Strelitz, Raven Row, Rachel Harlow, Katharina Worf, Matt Atkins, Crispin Kelly, Ashley Wilde-Evans, Stephanie Macdonald, Markus Lähteenmäki, Matthew Hearn. -

Environmental Draft Statement

DRAFT PHASE ONE ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Non-Technical Summary 2 | HS2 Phase One Draft Environmental Statement | Non-Technical Summary High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, © Queen’s Printer and Controller of Her To order further copies contact: 2nd Floor, Eland House, Majesty’s Stationery Office, 2013, except where Bressenden Place, otherwise stated DfT Publications London SW1E 5DU Tel: 0300 123 1102 Copyright in the typographical arrangement Web: www.dft.gov.uk/orderingpublications Telephone 020 7944 4908 rests with the Crown. Product code : ES/01 General email enquiries [email protected] You may re-use this information (not including Website: www.hs2.org.uk logos or third-party material) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of Printed in Great Britain on paper containing the Open Government Licence. To view this at least 75% recycled fibre. licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third-party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. ENGINE FOR GROWTH HS2 Phase One Draft Environmental Statement | Non-Technical Summary Foreword The draft Environmental Statement HS2 Ltd is consulting on the draft ES in order to Proposed changes to the January 2012 scheme When the Government submits a hybrid Bill to inform interested parties on the design of the scheme Since the Secretary of State published the proposed Parliament in late 2013, seeking powers to build a and the likely environmental effects with a view to route in January 2012, work has continued to refine new high speed railway between London and the completion of the formal ES. -

MOSSLEY STALYBRIDGE Broadbottom Hollingworth

Tameside.qxp_Tameside 08/07/2019 12:00 Page 1 P 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ST MA A 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Lydgate 0 D GI RY'S R S S D 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 A BB RIV K T O E L 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 8 9 SY C R C KES L A O 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 E 8 8 . N Y LAN IT L E E C 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 L 3 3 RN M . HO K R MANCHESTE Hollins 404T000 D R ROAD The Rough 404000 P A A E O Dacres O N HOLM R FIRTH ROAD R A T L E E R D D ANE L N L I KIL O BAN LD O N K O S LAN A A E H R Waterside D - L I E E Slate - Z V T L E D I I L A R R A E Pit Moss F O W R W D U S Y E N E L R D C S A E S D Dove Stone R O Reservoir L M A N E D Q OA R R U E I T C S K E H R C Saddleworth O IN N SPR G A V A A M Moor D M L D I E L A L Quick V O D I R E R Roaches E W I Lower Hollins Plantation E V V I G E R D D E K S C D I N T T U A Q C C L I I R NE R R O A L L Greave T O E T E TAK Dove Stone E M S IN S S I I Quick Edge R Moss D D O A LOWER HEY LA. -

Sir Hugh Casson Interviewed by Cathy Courtney: Full Transcript of the Interview

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH NATIONAL LIFE STORIES LEADERS OF NATIONAL LIFE Sir Hugh Casson Interviewed by Cathy Courtney C408/16 This transcript is copyright of the British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road NW1 2DB 020 7412 7404 [email protected] IMPORTANT Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators ([email protected]) British Library Sound Archive National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C408/16/01-24 Playback no: F1084 – F1093; F1156 – F1161; F1878 – F1881; F2837 – F2838; F6797 Collection title: Leaders of National Life Interviewee’s surname: Casson Title: Mr Interviewee’s forename: Hugh Sex: Male Occupation: Architect Date and place of birth: 1910 - 1999 Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: Dates of recording: 1990.02.13, 1990.02.16, 1990.02.19, 1990.03.13, 1990.04.19, 1990.05.11, 1990.05.22, 1990.08.28, 1990.07.31, 1990.08.07, 1991.05.22, 1991.06.03, 1991.06.18, 1991.07.13 Location of interview: Interviewer's home, National Sound Archive and Interviewee's home Name of interviewer: Cathy Courtney Type of recorder: Marantz CP430 Type of tape: TDK 60 Mono or stereo: Stereo Speed: N/A Noise reduction: Dolby B Original or copy: Original Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Interviewer’s comments: Sir Hugh Casson C408/016/F1084-A Page 1 F1084 Side A First interview with Hugh Casson - February 13th, 1990. -

July-August 2015

July-August 2015 In This Issue Opening Times #50th: Half a century of Tower Hamlets Coming Soon! William Whiffin's East End Upcoming events Recent events Pamphlet Collection Catalogued New acquisition Photography volunteer wanted Picture of the month Opening Times Last chance to see! Tues: 10am-5pm #50TH: Half a century of Tower Hamlets Wed: 9am-5pm Thu: 9am-8pm If you haven't caught this fascinating exhibition yet, you have Fri: closed until Thursday 6 August. Don't miss it! As well as looking at Sat: (1st & 3rd of the the last 50 years, the exhibition delves back into local month): 9am-5pm government in Tower Hamlets over hundreds of years, using Sun, Mon: closed rarely-seen original archives and artefacts. These include a wonderful manuscript map of Bethnal Green which is over three hundred years old and a Poplar minute book dating Contact Us from 1593. A striking oil painting of George Lansbury, loaned by members of the Lansbury family, is on show for the first Send us your enquiry via email, time. The borough's town halls and also its regeneration are phone or letter at explored extensively with illustrations, press cuttings and photographs. There is also a section on political control in Tower Hamlets Local History which the changing political make-up of the borough is Library and Archives represented in a fascinating series of maps, with displays of 277 Bancroft Road ephemera relating to the Lib-Dem 'neighbourhood' years London E1 4DQ (1986-1994), the Millwall by-election of 1993, and the origins of Bengali people's involvement in local politics. -

Domestic 4: the Modern House and Housing

Domestic 4: Modern Houses and Housing Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of- selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. This guide, one of four on different types of Domestic Buildings, covers modern houses and housing. -

Bromley (Lewisham)

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REVIEW OF GREATER LONDON, THE LONDON BOROUGHS AND THE CITY OF LONDON LONDON BOROUGH OF BROMLEY Boundary with : LEWISHAM LB LAMBETH DARTFORD BROM -Y SEVENOAKS TANDRIDGE REPORT NO. 641 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO 641 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN MR K F J ENNALS CB MEMBERS MR G R PRENTICE MRS H R V SARKANY MR C W SMITH PROFESSOR K YOUNG RT HON MICHAEL HOWARD HP QC SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT REVIEW OF GREATER LONDON, THE LONDON BOROUGHS AND THE CITY OF LONDON LONDON BOROUGH OF BROMLEY AND ITS BOUNDARY WITH THE LONDON BOROUGH OF LEWISHAM COMMISSION'S FINAL REPORT INTRODUCTION 1. This report contains our final proposals for the London Borough of Bromley's boundary with the London Borough of Lewisham. In the main, we have proposed limited changes to remove anomalies, for example, where properties are divided by the boundary. However, we have also sought to unite areas of continuous development where this has appeared to be in the interests of effective and convenient local government. Our report explains how we arrived at our proposals. 2. On 1 April 1987 we announced the start of a review of Greater London, the London boroughs and the City of London, as part of the programme of reviews we are required to undertake by virtue of section 48(1) of the Local Government Act 1972. We wrote to each of the local authorities concerned. 3. Copies of our letter were sent to the adjoining London boroughs; the appropriate county, district and parish councils bordering Greater London; the local authority associations; Members of Parliament with constituency interests; and the headquarters of the main political parties.