Robin Hood Gardens Blackwall Reach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open House Feb 2002 Issue 6 (PDF 607KB)

Inside this issue... G How the referendum will work – page 2 G Why the referendum matters – page 3 G Your block-by-block guide to voting – pages 5-8 Opportunities and choice Issue No.6 February 2002 DON’T SLAM THE DOOR ON THETower FUTUREKeep your options open – blocks bite dropping out means missing out! the dust... n February, ten- spend at least £590 involved in decisions ants and lease- million over the next about their homes. I Tower holders will be five years on major That’s why we are blocks Iinvited to take repairs and improve- holding this referen- Antrim part in the Housing ments to your hous- dum. House and Choice referendum ing. However, the At this stage we are Cavan – the biggest hous- most it can expect to not asking people to House, were ing consultation raise from rents and make any major deci- dramatically ever carried out by Government subsidy sions about the future demolished the council. is £300 million. That’s of their estate. by This is your oppor- a shortfall of £290 This is simply the controlled tunity to have your million. opportunity for each explosion on say and to get The council cannot estate to say whether Sunday 20 involved in further afford to borrow that it wants to be January. The consultation on ways amount of money. It involved in the next former to bring in much- cannot put up rents stage of the Housing council needed investment enough to bridge the Choice consultation blocks are for your estate. gap. However, there and work with the to be Why is the council are ways of bringing council on ways to holding the referen- in additional invest- bring in the invest- replaced dum? Annual income ment. -

Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events

November 2016 Brick Lane Born: Exhibition and Events Gilbert & George contemplate one of Raju's photographs at the launch of Brick Lane Born Our main exhibition, on show until 7 January is Brick Lane Born, a display of over forty photographs taken in the mid-1980s by Raju Vaidyanathan depicting his neighbourhood and friends in and around Brick Lane. After a feature on ITV London News, the exhibition launched with a bang on 20 October with over a hundred visitors including Gilbert and George (pictured), a lively discussion and an amazing joyous atmosphere. Comments in the Visitors Book so far read: "Fascinating and absorbing. Raju's words and pictures are brilliant. Thank you." "Excellent photos and a story very similar to that of Vivian Maier." "What a fascinating and very special exhibition. The sharpness and range of photographs is impressive and I am delighted to be here." "What a brilliant historical testimony to a Brick Lane no longer in existence. Beautiful." "Just caught this on TV last night and spent over an hour going through it. Excellent B&W photos." One launch attendee unexpectedly found a portrait of her late father in the exhibition and was overjoyed, not least because her children have never seen a photo of their grandfather during that period. Raju's photos and the wonderful stories told in his captions continue to evoke strong memories for people who remember the Spitalfields of the 1980s, as well as fascination in those who weren't there. An additional event has been added to the programme- see below for details. -

Download the Development Showcase Here

THE DEVELOPMENT SHOWCASE WELCOME ondon is one of the most popular capital in the past year, CBRE has continued global cities, home to over eight million to provide exceptional advice and innovative L residents from all over the world. The solutions to clients, housebuilders and English language, convenient time zone, developers, maintaining our strong track world-class education system, diverse culture record of matching buyers and tenants with and eclectic mix of lifestyles, make London their ideal homes. one of the most exciting places to call home and also the ideal place to invest in. Regeneration in London is on a scale like no other, with many previously neglected With four world heritage sites, eight spacious areas being transformed into thriving new royal parks and over 200 museums and communities and public realms, creating galleries, London acts as a cultural hub for jobs and economic growth. This large- both its residents and the 19 million visitors scale investment into regeneration and it receives every year. The London economy, placemaking is contributing to the exciting including financial services, life sciences and constant evolution of the capital that and many of the world’s best advisory we are witnessing and is a crucial reason as firms not only attract people from all over to why people are still choosing to invest in the world to study and work here, but also London real estate. London’s regeneration contribute towards the robust UK economy plan will be enhanced further when the that stands strong throughout uncertainty. It Elizabeth Line (previously Crossrail) will is no surprise that the property market has open in December, reducing journey times mirrored this resilience in the past few years. -

Finding Peace and Nature in the City Lunch at Maureen's Pie & Mash

ISSUE 01 SEPTEMBER 2018 C CLIPPERWALK EAT THINK Innovative communities in Finding peace and Lunch at Maureen's What drives Poplar and Canning Town nature in the city Pie & Mash creative migration? C Welcome to the first issue of Clipper, a magazine that champions the creative and innovative communities of London’s East End. Running across East India Docks and Poplar to Canning Town, Clipper tells the unique stories of the people and businesses who increasingly call this area home. London’s strength lies in its diversity, its adaptability, and its creativity. In this issue, we explore the eastward migration of London’s creative industries, and meet the personalities behind this shift. On pg 6 our guest columnist David Michon tackles the question: how are creative neighbourhoods born? From the local institution that is Maureen’s pie shop on pg 13 to a perfume maker reshaping the traditions of his trade on pg 16, it is this combination of the old and the new, entrepreneurial heritage and contemporary innovation, that makes this corner of East London such an inspiring destination for creative minds to both live and work. CONTRIBUTORS WORDS PHOTOGRAPHY ILLUSTRATION ON THE COVER Megan Carnegie, Ellie Harrison, Sophia Spring Abbey Lossing, Andrew Joyce, Jean Kern, head baker, E5 Roasthouse at Poplar Union Ella Braidwood, Charlotte Irwin, Ilya Milstein, Tom Woolley, David Michon Martina Paukova Printed and bound in London by Park Communications Ltd. Copyright © 2018 Courier Holdings Ltd. All rights reserved. CLIPPER 4 p.16 p.13 CONTENTS Agenda: Creative migration 06 The merchants: Maureen’s pie and mash 13 Headspace: Gallivant perfumes 16 Landmark: London’s only lighthouse 24 Creating space: Republic’s Import and Export buildings 26 Meet the team: Creative agency Threepipe 30 Map 34 Directory 35 p.30 p.26 p.24 5 CONTENTS CLIPPER 6 AGENDA WHAT ATTRACTS CREATIVE TALENT TO A NEIGHBOURHOOD? David Michon, former editor of architecture and design magazine Icon, explores how creative neighbourhoods are born. -

Strategic Development Date: 6Th March 2012 Classification

Committee: Date: Classification: Agenda Item No: Strategic Development 6th March 2012 Unrestricted 6.5 Report of: Title: Planning Application for Decision Corporate Director of Development and Renewal Ref No: PA/11/3765 Case Officer: Nasser Farooq Ward(s): Limehouse 1. APPLICATION DETAILS Location: Former Blessed John Roche Secondary School, Upper North Street, London E14 6ER Existing Use: Formally a vacant school – currently a building site relating to a planning permission reference PA/10/00161 Proposal: Construction of 239 dwellings within two buildings extending to between five and ten storeys with landscaping and 92 car parking spaces. (This application is a revision of Blocks C and D as approved within planning permission dated 21st September 2010, reference PA/10/161, and comprises an additional 12 residential units upon the 227 previously approved within these blocks) Drawing Nos: PL(B)005 A, PL(4)009, PL(4)010, PL(4)011, PL(4)012, PL(4)013, PL(4)014, PL(4)015, PL(4)016, PL(4)017, PL(4)018, PL(4)019, PL(4)020, PL(4)021, PL(4)021, PL(4)022, PL(4)023, PL(4)026, PL(4)059, PL(4)060, PL(4)061, PL(4)062, PL(4)063, PL(4)064, PL(4)065, PL(4)069, PL(4)070, PL(4)071, PL(4)072, PL(4)073, PL(4)074, PL(4)075, PL(4)076, PL(4)077, PL(4)078, PL(4)101, PL(4)102, PL(4)103, PL(4)104, PL(4)105, PL(4)110, PL(4)112, PL(4)113, PL(4)115 and PL(4)117. -

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017 Part of the London Plan evidence base COPYRIGHT Greater London Authority November 2017 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 Copies of this report are available from www.london.gov.uk 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Contents Chapter Page 0 Executive summary 1 to 7 1 Introduction 8 to 11 2 Large site assessment – methodology 12 to 52 3 Identifying large sites & the site assessment process 53 to 58 4 Results: large sites – phases one to five, 2017 to 2041 59 to 82 5 Results: large sites – phases two and three, 2019 to 2028 83 to 115 6 Small sites 116 to 145 7 Non self-contained accommodation 146 to 158 8 Crossrail 2 growth scenario 159 to 165 9 Conclusion 166 to 186 10 Appendix A – additional large site capacity information 187 to 197 11 Appendix B – additional housing stock and small sites 198 to 202 information 12 Appendix C - Mayoral development corporation capacity 203 to 205 assigned to boroughs 13 Planning approvals sites 206 to 231 14 Allocations sites 232 to 253 Executive summary 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Executive summary 0.1 The SHLAA shows that London has capacity for 649,350 homes during the 10 year period covered by the London Plan housing targets (from 2019/20 to 2028/29). This equates to an average annualised capacity of 64,935 homes a year. -

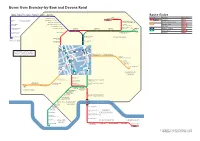

Buses from Bromley-By-Bow and Devons Road

Buses from Bromley-by-Bow and Devons Road Homerton Brooksbys Walk Kenworthy Hackney Wick Hackney Monier Road Hospital Homerton Road Eastway Wick Wansbeck Road Route finder Bus route Towards Bus stops Jodrell Road Wick Lane Stratford International Á Â Clapton Parnell Road Waterside Close 108 108 Lewisham Pond HACKNEY Stratford City Bus Station Parnell Road Old Ford Road for Stratford Stratford International » ½ Hackney Downs Parnell Road Roman Road Market Pool Street 323 Canning Town · ¸ ¹ Downs Road London Aquatics Centre Fairfield Road Tredegar Road Mile End ³ µ ¶ Carpenters Road Kingsland High Street Fairfield Road Bow Bus Garage Bow Road High Street High Street Gibbins Road 488 Dalston Junction ¬ ° Shacklewell Lane Bow Church Marshgate Lane Warton Road Stratford Bus Station D8 Crossharbour ¬ ® Stratford High Street D8 Dalston Kingsland Bow Church Carpenters Road Stratford ¯ ° Bromley High Street Dalston Junction Bow Interchange 488 Campbell Road STRATFORD Bow Road DALSTON St. Leonards Street Campbell Road Grace Street Rounton Road D R K EET C STR O N C LWI N TA HA AY BL ILL W Bromley-by-Bow NH AC RAI K C WA The yellow tinted area includes every bus P A DE ° UR M ROU R stop up to about one-and-a-half miles from V L EEV ¬ P D L TU ONS RD Bromley-by-Bow and Devons Road. Main B Y S NTON E E Twelvetrees Crescent Twelvetrees Crescent L S T N stops are shown in the white area outside. L R ¹ ProLogis Park Crown Records Building REET D NEL N R School O REET D A ¸ S ST A ³ Cody Road D ON R DEV T SWA ROA ½ Á School O North Crescent Business Centre R T µ H D G ER I ET LL Devons N STRE ¯ SO APPR N Star Lane EMP EN Road RD D S D P E T RD Manor Road . -

London's Housing Struggles Developer&Housing Association Dec 2014

LONDON’S HOUSING STRUGGLES 2005 - 2032 47 68 30 13 55 20 56 26 62 19 61 44 43 32 10 41 1 31 2 9 17 6 67 58 53 24 8 37 46 22 64 42 63 3 48 5 69 33 54 11 52 27 59 65 12 7 35 40 34 74 51 29 38 57 50 73 66 75 14 25 18 36 21 39 15 72 4 23 71 70 49 28 60 45 16 4 - Mardyke Estate 55 - Granville Road Estate 33 - New Era Estate 31 - Love Lane Estate 41 - Bemerton Estate 4 - Larner Road 66 - South Acton Estate 26 - Alma Road Estate 7 - Tavy Bridge estate 21 - Heathside & Lethbridge 17 - Canning Town & Custom 13 - Repton Court 29 - Wood Dene Estate 24 - Cotall Street 20 - Marlowe Road Estate 6 - Leys Estate 56 - Dollis Valley Estate 37 - Woodberry Down 32 - Wards Corner 43 - Andover Estate 70 - Deans Gardens Estate 30 - Highmead Estate 11 - Abbey Road Estates House 34 - Aylesbury Estate 8 - Goresbrook Village 58 - Cricklewood Brent Cross 71 - Green Man Lane 44 - New Avenue Estate 12 - Connaught Estate 23 - Reginald Road 19 - Carpenters Estate 35 - Heygate Estate 9 - Thames View 61 - West Hendon 72 - Allen Court 47 - Ladderswood Way 14 - Maryon Road Estate 25 - Pepys Estate 36 - Elmington Estate 10 - Gascoigne Estate 62 - Grahame Park 15 - Grove Estate 28 - Kender Estate 68 - Stonegrove & Spur 73 - Havelock Estate 74 - Rectory Park 16 - Ferrier Estate Estates 75 - Leopold Estate 53 - South Kilburn 63 - Church End area 50 - Watermeadow Court 1 - Darlington Gardens 18 - Excalibur Estate 51 - West Kensingston 2 - Chippenham Gardens 38 - Myatts Fields 64 - Chalkhill Estate 45 - Tidbury Court 42 - Westbourne area & Gibbs Green Estates 3 - Briar Road Estate -

Blackwall Reach One of London's Most Significant Regeneration Projects

Blackwall Reach One of London’s most significant regeneration projects 1 Blackwall Reach, London E14 Blackwall is a place with a rich history and an exciting future. Blackwall Reach is set to transform the local area providing 1,575 new homes, beautiful open spaces, new shops and community facilities, delivered over four phases. The first phase comprises a collection of contemporary 1, 2 and 3 bedroom apartments and penthouses, many of which will offer stunning river or city views. Included in this is a remarkable 24-storey tower, which will anchor the heart of this vibrant community. Formerly a pioneering 1960s urban estate, Blackwall Reach is fast becoming one of Europe’s most dynamic regeneration schemes. This welcoming community thrives thanks to its impressive transport links and open spaces, which will include a revitalised Millennium Green, and will be expanded thanks to Station Square. Blackwall Reach has been designed to engender the same sense of community as its historic predecessor. Designed to create a strong sense of arrival at Blackwall DLR station, Blackwall Reach will establish a benchmark of quality in the area. Expect nothing but excellence from the eco-friendly specification at Blackwall Reach. The residences All the apartments and penthouses at Blackwall Reach have been designed to provide luxurious comfort, with a five-star concierge service to make your life stress free. From stylish kitchens and bathrooms to winter gardens, each apartment features underfloor heating, engineered timber flooring, large format porcelain tiles and built-in sliding wardrobes. Come home to style at Blackwall Reach. Features – 5-star concierge service – Residents’ lounge area to each building – Tranquil park and landscaped areas – Shops and community facilities – Cycle store – 10 year NHBC warranty Blackwall Reach 2–3 London E14 Ideally located for the Highbury & City and Canary Wharf Islington Caledonian Road Canonbury Stratford Blackwall Reach is perfectly London is still the capital for global business King’s Cross St. -

Sandars Lectures 2007: Conversations with Maps

SANDARS LECTURES 2007: CONVERSATIONS WITH MAPS Sarah Tyacke CB Lecture III: There are maps and there are maps – motives, markets and users As Christian Jacob put it ‘There are maps and there are maps’. More prosaically the nature of them depends on what you want the map or chart for and how you the reader perceive it? This third lecture is about what drove the cartographic activity internally and externally and how did it manifest itself in England and the rest of maritime Europe through its distributors, patrons and readers. This is probably the most challenging subject, first articulated in embryonic form as part of the history of cartography’s remit in the 1970s by David Woodward (as we saw in lecture I) and developed thereafter as the history of cartography took a ‘second turn’ and embraced social context. This ‘second turn’ challenged the inevitability of progress in cartography and understood that cartography was just as much a product of its society as other texts. In the case of Brian Harley he took this further arguing powerfully, from the examples he found, that in the early modern period with the rise of the nation state and European expansion ‘cartography was primarily a form of political discourse concerned with the acquisition and maintenance of power’ ( Imago Mundi 1988, 40 pp. 57-76). One might say the same of archives and libraries which spent (and do spend) their time ordering knowledge in the shape of books and manuscripts. In the case of a National Archives there is a clear explicit connection between the state and the archive; but even here within the archive and within the map there are other human elements at work as well, even subversive at least when it comes to interpreting them. -

Iod Neighbourhood Basic Plan - Infrastructure Baseline Analysis V1 1St April 2019 Infrastructure Baseline Analysis for Planning Committee

IoD Neighbourhood Basic Plan - Infrastructure Baseline Analysis V1 1st April 2019 Infrastructure Baseline Analysis for Planning Committee Note negative numbers = gap to be filled. Positive numbers = No gap, excess capacity. tbc = to be added once up to date data sourced Demand = Current Population + Current Provision of Infrastructure Approved Planning Applications Gap to be Category / Type Measure Existing Consented Total Need filled % Gap Comments Education Nursery No. of forms of entry 15 9 24 63 (39) (62%) Number of nurseries 15 (0) 15 21 (6) (29%) Primary school No. of forms of entry 18 6 24 63 (39) (62%) Number of schools 10 3 13 21 (8) (38%) Secondary school No. of forms of entry 13 6 19 34 (16) (45%) Number of schools 2 1 3 6 (3) (47%) Special Education Provision No. of forms of entry 0 0 0 5 (5) (100%) Number of schools 0 0 0 2 (2) (100%) There are no Special Needs school in the area currently Health GP Surgery spaces Number of doctors 30 18 48 54 (6) (10%) NHS like new surgeries to be around 10 Doctors in size Pharmacy Number of pharmacy People 8 #VALUE!0 8 120 (4)8 (33%) Dentist Number of dentist 10 0 10 15 (5) (33%) Birthing centre Number of centre 1 0 1 1 (0) (33%) Proxy for other health services Open Space Publicly Accessible Open Space Hectares 21 6 27 116 (89) (77%) Playgrounds separate Square meters 580 tbc tbc 158,555 tbc up to date data to be sourced Library, Sports & Leisure Library ReQuirements Per square meter 1,382 0 1,382 2,893 (1,511)0 (52%) Does not include bigger Wood Wharf Idea store Swimming Pools Per square -

NQ.PA.15. Heritage Assessment – July 2020

NQ.PA.15 NQ.LBC.03 North Quay Heritage Assessment Peter Stewart Consultancy July 2020 North Quay – Heritage Assessment Contents Executive Summary 1 1 Introduction 3 2 Heritage planning policy and guidance 7 3 The Site and its heritage context 15 4 Assessment of effect of proposals 34 5 Conclusion 41 Appendix 1 Abbreviations 43 July 2020 | 1 North Quay – Heritage Assessment Executive Summary This Heritage Assessment has been prepared in support of the application proposals for the Site, which is located in Canary Wharf, in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets (”LBTH”). The assessment considers the effect of the Proposed Development in the context of heritage legislation and policy on a number of designated heritage assets, all of which are less than 500m from the boundary of the Site. These designated heritage assets have been identified as those which could be potentially affected, in terms of their ‘significance’ as defined in the NPPF, as a result of development on the Site. It should be read in conjunction with the Built Heritage Assessment (“BHA”), which assesses the effect of the Proposed Development on the setting of heritage assets in the wider area, and the Townscape and visual impact assessment (“TVIA”), both within the Environmental Statement Volume II (ref NQ.PA.08 Vol. 2), also prepared by Peter Stewart Consultancy. A section of the grade I listed Dock wall runs below ground through the Site. This aspect of the project is assessed in detail in the Archaeological Desk Based Assessment accompanying the outline planning application and LBC (ref. NQ.PA.26/ NQ.LBC.07) and the Outline Sequence of Works for Banana Wall Listed Building Consent report (ref.