Domestic 4: the Modern House and Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hundreds of Homes for Sale See Pages 3, 4 and 5

Wandsworth Council’s housing newsletter Issue 71 July 2016 www.wandsworth.gov.uk/housingnews Homelife Queen’s birthday Community Housing cheat parties gardens fined £12k page 10 and 11 Page 13 page 20 Hundreds of homes for sale See pages 3, 4 and 5. Gillian secured a role at the new Debenhams in Wandsworth Town Centre Getting Wandsworth people Sarah was matched with a job on Ballymore’s Embassy Gardens into work development in Nine Elms. The council’s Work Match local recruitment team has now helped more than 500 unemployed local people get into work and training – and you could be next! The friendly team can help you shape up your CV, prepare for interview and will match you with a live job or training vacancy which meets your requirements. Work Match Work They can match you with jobs, apprenticeships, work experience placements and training courses leading to full time employment. securing jobs Sheneiqua now works for Wandsworth They recruit for dozens of local employers including shops, Council’s HR department. for local architects, professional services, administration, beauti- cians, engineering companies, construction companies, people supermarkets, security firms, logistics firms and many more besides. Work Match only help Wandsworth residents into work and it’s completely free to use their service. Get in touch today! w. wandsworthworkmatch.org e. [email protected] t. (020) 8871 5191 Marc Evans secured a role at 2 [email protected] Astins Dry Lining AD.1169 (6.16) Welcome to the summer edition of Homelife. Last month, residents across the borough were celebrating the Queen’s 90th (l-r) Cllr Govindia and CE Nick Apetroaie take a glimpse inside the apartments birthday with some marvellous street parties. -

Johnson 1 C. Johnson: Social Contract And

C. Johnson: Social Contract and Energy in Pimlico ORIGINAL ARTICLE District heating as heterotopia: Tracing the social contract through domestic energy infrastructure in Pimlico, London Charlotte Johnson UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources, University College London, London, WC1H 0NN, UK Corresponding author: Charlotte Johnson; e-mail: [email protected] The Pimlico District Heating Undertaking (PDHU) was London’s first attempt at neighborhood heating. Built in the 1950s to supply landmark social housing project Churchill Gardens, the district heating system sent heat from nearby Battersea power station into the radiators of the housing estate. The network is a rare example in the United Kingdom, where, unlike other European states, district heating did not become widespread. Today the heating system supplies more than 3,000 homes in the London Borough of Westminster, having survived the closure of the power station and the privatization of the housing estate it supplies. Therefore, this article argues, the neighborhood can be understood as a heterotopia, a site of an alternative sociotechnical order. This concept is used to understand the layers of economic, political, and technological rationalities that have supported PDHU and to question how it has survived radical changes in housing and energy policy in the United Kingdom. This lens allows us to see the tension between the urban planning and engineering perspective, which celebrates this Johnson 1 system as a future-oriented “experiment,” and the reality of managing and using the system on the estate. The article analyzes this technology-enabled standard of living as a social contract between state and citizen, suggesting a way to analyze contemporary questions of district energy. -

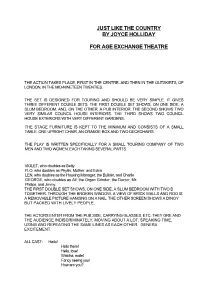

JLTC Playscript

JUST LIKE THE COUNTRY BY JOYCE HOLLIDAY FOR AGE EXCHANGE THEATRE THE ACTION TAKES PLACE, FIRST IN THE CENTRE, AND THEN IN THE OUTSKIRTS, OF LONDON, IN THE MID-NINETEEN TWENTIES. THE SET IS DESIGNED FOR TOURING AND SHOULD BE VERY SIMPLE. IT GIVES THREE DIFFERENT DOUBLE SETS. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM, AND, ON THE OTHER, A PUB INTERIOR. THE SECOND SHOWS TWO VERY SIMILAR COUNCIL HOUSE INTERIORS. THE THIRD SHOWS TWO COUNCIL HOUSE EXTERIORS WITH VERY DIFFERENT GARDENS. THE STAGE FURNITURE IS KEPT TO THE MINIMUM AND CONSISTS OF A SMALL TABLE, ONE UPRIGHT CHAIR, AN ORANGE BOX AND TWO DECKCHAIRS. THE PLAY IS WRITTEN SPECIFICALLY FOR A SMALL TOURING COMPANY OF TWO MEN AND TWO WOMEN, EACH TAKING SEVERAL PARTS. VIOLET, who doubles as Betty FLO, who doubles as Phyllis, Mother, and Edna LEN, who doubles as the Housing Manager, the Builder, and Charlie GEORGE, who doubles as Alf, the Organ Grinder, the Doctor, Mr. Phillips, and Jimmy. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM WITH TWO B TOGETHER. THROUGH THE BROKEN WINDOW, A VIEW OF BRICK WALLS AND ROO IS A REMOVABLE PICTURE HANGING ON A NAIL. THE OTHER SCREEN SHOWS A DINGY BUT PACKED WITH LIVELY PEOPLE. THE ACTORS ENTER FROM THE PUB SIDE, CARRYING GLASSES, ETC. THEY GRE AND THE AUDIENCE INDISCRIMINATELY, MOVING ABOUT A LOT, SPEAKING TIME, USING AND REPEATING THE SAME LINES AS EACH OTHER. GENERA EXCITEMENT. ALL CAST: Hello! Hello there! Hello, love! Watcha, mate! Fancy seeing you! How are you? How're you keeping? I'm alright. -

The Architecture of Sir Ernest George and His Partners, C. 1860-1922

The Architecture of Sir Ernest George and His Partners, C. 1860-1922 Volume II Hilary Joyce Grainger Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph. D. The University of Leeds Department of Fine Art January 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Notes to Chapters 1- 10 432 Bibliography 487 Catalogue of Executed Works 513 432 Notes to the Text Preface 1 Joseph William Gleeson-White, 'Revival of English Domestic Architecture III: The Work of Mr Ernest George', The Studio, 1896 pp. 147-58; 'The Revival of English Domestic Architecture IV: The Work of Mr Ernest George', The Studio, 1896 pp. 27-33 and 'The Revival of English Domestic Architecture V: The Work of Messrs George and Peto', The Studio, 1896 pp. 204-15. 2 Immediately after the dissolution of partnership with Harold Peto on 31 October 1892, George entered partnership with Alfred Yeates, and so at the time of Gleeson-White's articles, the partnership was only four years old. 3 Gleeson-White, 'The Revival of English Architecture III', op. cit., p. 147. 4 Ibid. 5 Sir ReginaldýBlomfield, Richard Norman Shaw, RA, Architect, 1831-1912: A Study (London, 1940). 6 Andrew Saint, Richard Norman Shaw (London, 1976). 7 Harold Faulkner, 'The Creator of 'Modern Queen Anne': The Architecture of Norman Shaw', Country Life, 15 March 1941 pp. 232-35, p. 232. 8 Saint, op. cit., p. 274. 9 Hermann Muthesius, Das Englische Haus (Berlin 1904-05), 3 vols. 10 Hermann Muthesius, Die Englische Bankunst Der Gerenwart (Leipzig. 1900). 11 Hermann Muthesius, The English House, edited by Dennis Sharp, translated by Janet Seligman London, 1979) p. -

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities This Page Intentionally Left Blank H6309-Prelims.Qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page Iii

H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page i Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities This page intentionally left blank H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page iii Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities Mike Jenks and Nicola Dempsey AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON • NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Architectural Press is an imprint of Elsevier H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page iv Architectural Press An imprint of Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington, MA 01803 First published 2005 Editorial matter and selection Copyright © 2005, Mike Jenks and Nicola Dempsey. All rights reserved Individual contributions Copyright © 2005, the Contributors. All rights reserved No parts of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 843830; fax: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 853333; e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’ and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’. -

2017 Annual Report Plc Redrow Sense of Wellbeing

Redrow plc Redrow Redrow plc Redrow House, St. David’s Park, Flintshire CH5 3RX 2017 Tel: 01244 520044 Fax: 01244 520720 ANNUAL REPORT Email: [email protected] Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 01 STRATEGIC REPORT STRATEGIC REDROW ANNUAL REPORT 2017 A Better Highlights Way to Live £1,660m £315m 70.2p £1,382m £250m 55.4p £1,150m £204m 44.5p GOVERNANCE REPORT GOVERNANCE 15 16 17 15 16 17 15 16 17 £1,660m £315m 70.2p Revenue Profit before tax Earnings per share +20% +26% +27% 17p 5,416 £1,099m 4,716 £967m STATEMENTS FINANCIAL 4,022 10p £635m 6p 15 16 17 15 16 17 15 16 17 Contents 17p 5,416 £1,099m Dividend per share Legal completions (inc. JV) Order book (inc. JV) SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION SHAREHOLDER STRATEGIC REPORT GOVERNANCE REPORT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SHAREHOLDER 01 Highlights 61 Corporate Governance 108 Independent Auditors’ INFORMATION +70% +15% +14% 02 Our Investment Case Report Report 148 Corporate and 04 Our Strategy 62 Board of Directors 114 Consolidated Income Shareholder Statement Information 06 Our Business Model 68 Audit Committee Report 114 Statement of 149 Five Year Summary 08 A Better Way… 72 Nomination Committee Report Comprehensive Income 16 Our Markets 74 Sustainability 115 Balance Sheets Award highlights 20 Chairman’s Statement Committee Report 116 Statement of Changes 22 Chief Executive’s 76 Directors’ Remuneration in Equity Review Report 117 Statement of Cash Flows 26 Operating Review 98 Directors’ Report 118 Accounting Policies 48 Financial Review 104 Statement of Directors’ 123 Notes to the Financial 52 Risk -

Who Is Council Housing For?

‘We thought it was Buckingham Palace’ ‘Homes for Heroes’ Cottage Estates Dover House Estate, Putney, LCC (1919) Cottage Estates Alfred and Ada Salter Wilson Grove Estate, Bermondsey Metropolitan Borough Council (1924) Tenements White City Estate, LCC (1938) Mixed Development Somerford Grove, Hackney Metropolitan Borough Council (1949) Neighbourhood Units The Lansbury Estate, Poplar, LCC (1951) Post-War Flats Spa Green Estate, Finsbury Metropolitan Borough Council (1949) Berthold Lubetkin Post-War Flats Churchill Gardens Estate, City of Westminster (1951) Architectural Wars Alton East, Roehampton, LCC (1951) Alton West, Roehampton, LCC (1953) Multi-Storey Housing Dawson’s Heights, Southwark Borough Council (1972) Kate Macintosh The Small Estate Chinbrook Estate, Lewisham, LCC (1965) Low-Rise, High Density Lambeth Borough Council Central Hill (1974) Cressingham Gardens (1978) Camden Borough Council Low-Rise, High Density Branch Hill Estate (1978) Alexandra Road Estate (1979) Whittington Estate (1981) Goldsmith Street, Norwich City Council (2018) Passivhaus Mixed Communities ‘The key to successful communities is a good mix of people: tenants, leaseholders and freeholders. The Pepys Estate was a monolithic concentration of public housing and it makes sense to break that up a bit and bring in a different mix of incomes and people with spending power.’ Pat Hayes, LB Lewisham, Director of Regeneration You have castrated communities. You have colonies of low income people, living in houses provided by the local authorities, and you have the higher income groups living in their own colonies. This segregation of the different income groups is a wholly evil thing, from a civilised point of view… We should try to introduce what was always the lovely feature of English and Welsh villages, where the doctor, the grocer, the butcher and the farm labourer all lived in the same street – the living tapestry of a mixed community. -

London and South East

London and South East nationaltrust.org.uk/groups 69 Previous page: Polesden Lacey, Surrey Pictured, this page: Ham House and Garden, Surrey; Basildon Park, Berkshire; kitchen circa 1905 at Polesden Lacey Opposite page: Chartwell, Kent; Petworth House and Park, West Sussex; Osterley Park and House, London From London living at New for 2017 Perfect for groups Top three tours Ham House on the banks Knole Polesden Lacey The Petworth experience of the River Thames Much has changed at Knole with One of the National Trust’s jewels Petworth House see page 108 to sweeping classical the opening of the new Brewhouse in the South East, Polesden Lacey has landscapes at Stowe, Café and shop, a restored formal gardens and an Edwardian rose Gatehouse Tower and the new garden. Formerly a walled kitchen elegant decay at Knole Conservation Studio. Some garden, its soft pastel-coloured roses The Churchills at Chartwell Nymans and Churchill at restored show rooms will reopen; are a particular highlight, and at their Chartwell see page 80 Chartwell – this region several others will be closed as the best in June. There are changing, themed restoration work continues. exhibits in the house throughout the year. offers year-round interest Your way from glorious gardens Polesden Lacey Nearby places to add to your visit are Basildon Park see page 75 to special walks. An intriguing story unfolds about Hatchlands Park and Box Hill. the life of Mrs Greville – her royal connections, her jet-set lifestyle and the lives of her servants who kept the Itinerary ideas house running like clockwork. -

Seminar Week People Commonly

AN ADDENDUM TO LONDON’S NATURAL HISTORY by R.S.R. Fitter PEOPLE COMMONLY FOUND IN LONDON DEBTS OF GRATITUDE INTRODUCTION OVERVIEW MONDAY – WEST TUESDAY – NORTH WEDNESDAY – SOUTH THURSDAY – EAST FRIDAY – CENTRAL DIRECTORY SEMINAR WEEK 2 2 – 2 8 O C T O B E R STUDIO TOM EMERSON D-ARCH ETH ZURICH MMXVII 2 PEOPLE COMMONLY FOUND IN LONDON* Cyril Amrein +41 79 585 83 34; Céline Bessire +41 79 742 94 91; Lucio Crignola +41 78 858 54 02; Toja Coray +41 79 574 40 69; Vanessa Danuser +41 78 641 10 65; Nick Drofiak +41 75 417 31 95; Boris Gusic +41 79 287 43 60; David Eckert +41 79 574 40 71; Tom Emerson; Zaccaria Exhenry +41 79 265 02 90; Gabriel Fiette +41 78 862 62 64; Kathrin Füglister +41 79 384 12 73; Pascal Grumbacher +41 79 595 60 95; Jonas Heller +41 78 880 12 55; Joel Hösle +41 77 483 57 67; Jens Knöpfel +41 77 424 62 38; Shohei Kunisawa +41 78 704 43 79; Juliette Martin +41 78 818 88 34; Khalil Mdimagh +41 76 416 52 25; Colin Müller +41 79 688 06 08; Alice Müller +41 79 675 40 76; Philip Shelley +44 77 5178 05 81; Tobia Rapelli +41 79 646 37 18; Daria Ryffel +41 79 881 67 70; Florian von Planta +41 79 793 52 55; Andreas Winzeler +41 79 537 63 30; Eric Wuite +41 77 491 61 57; Tian Zhou +41 78 676 96 15 DEBTS OF GRATITUDE Many thanks to Taran Wilkhu & family, Kim Wilkie, Rebecca Law, Robert Youngs, Angela Kidner, Alex Sainsbury, Juergen Teller Studio, James Green, Adam Willis, Paloma Strelitz, Raven Row, Rachel Harlow, Katharina Worf, Matt Atkins, Crispin Kelly, Ashley Wilde-Evans, Stephanie Macdonald, Markus Lähteenmäki, Matthew Hearn. -

6 5 2 1 3 7 9 8Q Y T U R E W I O G J H K F D S

i s 8 7q a 3 CITY 5 e TOWER HAMLETS k p 4 1 u rf 6w y 2 9 g j t do h RADICAL HOUSING LOCATIONS Virtual Radical Housing Tour for Open House Hope you enjoyed the virtual tour. Here’s a list of the sites we visited on the tour with some hopefully useful info. Please see the map on the website https://www.londonsights.org.uk/ and https://www.morehousing.co.uk/ ENJOY… No Site Year Address Borough Built VICTORIAN PHILANTHROPISTS Prince Albert’s Model Cottage 1851 Prince Consort Lodge, Lambeth Built for the Great Exhibition 1851 and moved here. Prince Albert = President of Society for Kennington Park, Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes. Prototype for social housing schemes. Kennington Park Place, 4 self-contained flats with inside WCs. Now HQ for Trees for Cities charity. London SE11 4AS Lambeth’s former workhouse – now the Cinema Museum 1880s The Cinema Museum Lambeth Charlie Chaplin sent here 1896 with mother and brother. Masters Lodge. 2 Dugard Way, Prince's, See website for opening times http://www.cinemamuseum.org.uk/ London SE11 4TH Parnell House 1850 Streatham Street Camden Earliest example of social housing in London. Same architect (Henry Roberts) as Model Cottage in Fitzrovia, London stop 1. Now owned by Peabody housing association (HA). Grade 2 listed. WC1A 1JB George Peabody statue Royal Exchange Avenue, City of London George Peabody - an American financier & philanthropist. Founded Peabody Trust HA with a Cornhill, charitable donation of £500k. London EC3V 3NL First flats built by Peabody HA 1863 Commercial Street Tower Now in private ownership London E1 Hamlets Peabody’s Blackfriars Road estate 1871 Blackfriars Road Southwark More typical ‘Peabody’ design. -

Urban Pamphleteer #2 Regeneration Realities

Regeneration Realities Urban Pamphleteer 2 p.1 Duncan Bowie# p.3 Emma Dent Coad p.5 Howard Read p.6 Loretta Lees, Just Space, The London Tenants’ Federation and SNAG (Southwark Notes Archives Group) p.11 David Roberts and Andrea Luka Zimmerman p.13 Alexandre Apsan Frediani, Stephanie Butcher, and Paul Watt p.17 Isaac Marrero- Guillamón p.18 Alberto Duman p.20 Martine Drozdz p.22 Phil Cohen p.23 Ben Campkin p.24 Michael Edwards p.28 isik.knutsdotter Urban PamphleteerRunning Head Ben Campkin, David Roberts, Rebecca Ross We are delighted to present the second issue of Urban Pamphleteer In the tradition of radical pamphleteering, the intention of this series is to confront key themes in contemporary urban debate from diverse perspectives, in a direct and accessible – but not reductive – way. The broader aim is to empower citizens, and inform professionals, researchers, institutions and policy- makers, with a view to positively shaping change. # 2 London: Regeneration Realities The term ‘regeneration’ has recently been subjected to much criticism as a pervasive metaphor applied to varied and often problematic processes of urban change. Concerns have focused on the way the concept is used as shorthand in sidestepping important questions related to, for example, gentrification and property development. Indeed, it is an area where policy and practice have been disconnected from a rigorous base in research and evidence. With many community groups affected by regeneration evidently feeling disenfranchised, there is a strong impetus to propose more rigorous approaches to researching and doing regeneration. The Greater London Authority has also recently opened a call for the public to comment on what regeneration is, and feedback on what its priorities should be.