Trauma, Fear, and Paranoia Lost and the Culture of 9/11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOST with a Good Book

The Lost Code: BYYJ C`1 P,YJ- LJ,1 Key Literary References and Influ- Books, Movies, and More on Your Favorite Subjects Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad CAS A CONR/ eAudiobook LOST on DVD A man journeys through the Congo and Lost Complete First Season contemplates the nature of good and evil. There are several references, especially in relation to Lost Season 2: Extended Experience Colonel’s Kurtz’s descent toward madness. Lost Season 3: The Unexplored Experience Lost. The Complete Fourth Season: The Expanded The Stand by Stephen King FIC KING Experience A battle between good and evil ensues after a deadly virus With a Good Book decimates the population. Producers cite this book as a Lost. The Complete Fifth Season: The Journey Back major influence, and other King allusions ( Carrie , On Writing , *Lost: Complete Sixth & Final Season is due for release 8/24/10. The Shining , Dark Tower series, etc.) pop up frequently. The Odyssey by Homer FIC HOME/883 HOME/ CD BOOK 883.1 HOME/CAS A HOME/ eAudiobook LOST Episode Guide Greek epic about Odysseus’s harrowing journey home to his In addition to the biblical episode titles, there are several other Lost wife Penelope after the Trojan War. Parallels abound, episode titles with literature/philosophy connections. These include “White especially in the characters of Desmond and Penny. Rabbit” and “Through the Looking Glass” from Carroll’s Alice books; “Catch-22”; “Tabula Rosa” (philosopher John Locke’s theory that the Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut FIC VON human mind is a blank slate at birth); and “The Man Behind the Curtain” A World War II soldier becomes “unstuck in time,” and is and “There’s No Place Like Home” ( The Wonderful Wizard of Oz ). -

LOST "Raised by Another" (YELLOW) 9/23/04

LOST “Raised by Another” CAST LIST BOONE................................Ian Somerhalder CHARLIE..............................Dominic Monaghan CLAIRE...............................Emilie de Ravin HURLEY...............................Jorge Garcia JACK.................................Matthew Fox JIN..................................Daniel Dae Kim KATE.................................Evangeline Lilly LOCKE................................Terry O’Quinn MICHAEL..............................Harold Perrineau SAWYER...............................Josh Holloway SAYID................................Naveen Andrews SHANNON..............................Maggie Grace SUN..................................Yunjin Kim WALT.................................Malcolm David Kelley THOMAS............................... RACHEL............................... MALKIN............................... ETHAN................................ SLAVITT.............................. ARLENE............................... SCOTT................................ * STEVE................................ * www.pressexecute.com LOST "Raised by Another" (YELLOW) 9/23/04 LOST “Raised by Another” SET LIST INTERIORS THE VALLEY - Late Afternoon/Sunset CLAIRE’S CUBBY - Night/Dusk/Day ENTRANCE * ROCK WALL - Dusk/Night/Day * INFIRMARY CAVE - Morning JACK’S CAVE - Night * LOFT - Day - FLASHBACK MALKIN’S HOUSE - Day - FLASHBACK BEDROOM - Night - FLASHBACK LAW OFFICES CONFERENCE ROOM - Day - FLASHBACK EXTERIORS JUNGLE - Night/Day ELSEWHERE - Day CLEARING - Day BEACH - Day OPEN JUNGLE - Morning * SAWYER’S -

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space With

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space with Flashbacks and Flash-forwards in the Series "Lost" Promotor: Auteur: Prof. Dr. S. Slembrouck Olga Berendeeva Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Afstudeerrichting: Master Engels Academiejaar 2008-2009 2e examenperiode For My Parents Who are so far But always so close to me Мои родителям, Которые так далеко, Но всегда рядом ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Stefaan Slembrouck for his interest in my work. I am grateful for all the encouragement, help and ideas he gave me throughout the writing. He was the one who helped me to figure out the subject of my work which I am especially thankful for as it has been such a pleasure working on it! Secondly, I want to thank my boyfriend Patrick who shared enthusiasm for my subject, inspired me, and always encouraged me to keep up even when my mood was down. Also my friend Sarah who gave me a feedback on my thesis was a very big help and I am grateful. A special thank you goes to my parents who always believed in me and supported me. Thanks to all the teachers and professors who provided me with the necessary baggage of knowledge which I will now proudly carry through life. iii Foreword In my previous research paper I wrote about film discourse, thus, this time I wanted to continue with it but have something new, some kind of challenge which would interest me. After a conversation with my thesis guide, Professor Slembrouck, we decided to stick on to film discourse but to expand it. -

„When Am I?“ – Zeitlichkeit in Der US-Serie LOST, Teil 2

GABRIELE SCHABACHER „When Am I?“ – Zeitlichkeit in der US-Serie LOST, Teil 2 Previously on … An der US-Serie LOST lässt sich eine systematische Nutzung der temporalen Di- mension beobachten: Auf den Ebenen von Erzählzeit und erzählter Zeit – das konnte der erste Teil dieses Beitrags zeigen – ist der Einsatz von story arcs überspan- nenden Flashbacks bzw. Flashforwards sowie eine handlungsseitig ausgeführte Thematisierung und Problematisierung von Zeitreisen und Teleportation für das Seriennarrativ zentral. Schon diese zeitlichen Relationen ermöglichen der Narra- tion entscheidende Inversionen und paradoxe Konstruktionen, die für die Serie LOST charakteristisch geworden sind. 1. Die dritte Zeit Eine dritte Dimension der Narration, um die es dem zweiten Teil dieses Beitrags geht, lässt sich nun keiner der beiden bisher thematisierten Gruppen eindeutig zuordnen, weder also der Erzählzeit und damit den stilistischen Mitteln im engeren Sinne, noch der erzählten Zeit, d. h. der inhaltlichen Ebene der Geschichte. Es handelt sich vielmehr um eine Gruppe von Phänomen, die sich durch eine spezifi - sche Übergängigkeit zwischen diesen beiden Kategorien auszeichnen. Daher wird im Folgenden auf die in der Serie geäußerten Vorahnungen, Time Loops, Bewusst- seinsreisen und Zeitsprünge einzugehen sein, um die Hybridisierung von Stilistik und Inhaltsmomenten der Narration zu verdeutlichen. Das Vorhandensein solcher hybrider Elemente ist es, das eine mögliche Erklärung für die besondere Faszinati- on an LOST und eine spezifi sch temporal motivierte Komplexität -

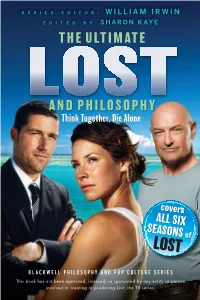

The Ultimate and Philosophy

PHILOSOPHY/POP CULTURE IRWIN SERIES EDITOR: WILLIAM IRWIN What are the metaphysics of time travel? EDITED BY SHARON KAYE How can Hurley exist in two places at the same time? THE ULTIMATE What does it mean for something to be possibly true in the fl ash-sideways universe? Does Jack have a moral obligation to his father? THE ULTIMATE What is the Tao of John Locke? Dude. So there’s, like, this island? And a bunch of us were on Oceanic fl ight 815 and we crashed on it. I kinda thought it was my fault, because of those numbers. I thought they were bad luck. We’ve seen the craziest things here, like a polar bear and a Smoke Monster, and we traveled through time back to the 1970s. And we met the Dharma dudes. Arzt even blew himself up. For a long time, I thought I was crazy. But now, I think it might have been destiny. The island’s made me question a lot of things. Like, why is it that Locke and Desmond have the same names as real philosophers? Why do so many of us have AND PHILOSOPHY trouble with our dads? Did Jack have a choice in becoming our leader? And what’s up Think Together, Die Alone with Vincent? I mean, he’s gotta be more than just a dog, right? I dunno. We’ve all felt pretty lost. I just hope we can trust Jacob, otherwise . whoa. With its sixth-season series fi nale, Lost did more than end its run as one of the most AND PHILOSOPHY talked-about TV programs of all time; it left in its wake a complex labyrinth of philosophical questions and issues to be explored. -

Learning from Ambiguously Labeled Images

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Technical Reports (CIS) Department of Computer & Information Science January 2009 Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images Timothee Cour University of Pennsylvania Benjamin Sapp University of Pennsylvania Chris Jordan University of Pennsylvania Ben Taskar University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports Recommended Citation Timothee Cour, Benjamin Sapp, Chris Jordan, and Ben Taskar, "Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images", . January 2009. University of Pennsylvania Department of Computer and Information Science Technical Report No. MS-CIS-09-07 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cis_reports/902 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Learning From Ambiguously Labeled Images Abstract In many image and video collections, we have access only to partially labeled data. For example, personal photo collections often contain several faces per image and a caption that only specifies who is in the picture, but not which name matches which face. Similarly, movie screenplays can tell us who is in the scene, but not when and where they are on the screen. We formulate the learning problem in this setting as partially-supervised multiclass classification where each instance is labeled ambiguously with more than one label. We show theoretically that effective learning is possible under reasonable assumptions even when all the data is weakly labeled. Motivated by the analysis, we propose a general convex learning formulation based on minimization of a surrogate loss appropriate for the ambiguous label setting. We apply our framework to identifying faces culled from web news sources and to naming characters in TV series and movies. -

Jack's Costume from the Episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H

Jack's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 572 Jack's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H... 300 Jack's suit from "There's No Place Like Home, Part 1" 200 573 Jack's suit from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 950 Home... 300 200 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown" 574 - 800 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown." Jack's bl... 300 200 Jack's Season Four costume 575 - 850 Jack's Season Four costume. Jack's gray pants, stripe... 300 200 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume 576 - 1,400 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume. Jack's white lab... 300 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs 200 577 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs. Jack's DHARMA - 1,300 scrub... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 578 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 1,100 H... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 579 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 900 H... 300 Kate's black dress from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 580 Kate's black dress from the episode, "There's No Place - 950 Li... 300 200 Kate's Season Four costume 581 - 950 Kate's Season Four costume. Kate's dark gray pants, d... 300 200 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown" 582 - 900 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown." K... 300 200 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist 583 - 5,000 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist." Kat.. -

LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy

"Accidental Intellectuals": LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy Author: Abigail Letak Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2615 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! This thesis is dedicated to everyone who has ever been obsessed with a television show. Everyone who knows that adrenaline rush you get when you just can’t stop watching. Here’s to finding yourself laughing and crying along with the characters. But most importantly, here’s to shows that give us a break from the day-to-day milieu and allow us to think about the profound, important questions of life. May many shows give us this opportunity as Lost has. Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my parents, Steve and Jody, for their love and support as I pursued my area of interest. Without them, I would not find myself where I am now. I would like to thank my advisor, Juliet Schor, for her immense help and patience as I embarked on combining my personal interests with my academic pursuits. Her guidance in methodology, searching the literature, and general theory proved invaluable to the completion of my project. I would like to thank everyone else who has provided support for me throughout the process of this project—my friends, my professors, and the Presidential Scholars Program. I’d like to thank Professor Susan Michalczyk for her unending support and for believing in me even before I embarked on my four years at Boston College, and for being the one to initially point me in the direction of sociology. -

LOST the Official Show Auction Catalog

LOST | The Auction 70 1-310-859-7701 Profiles in History | August 21 & 22, 2010 221. JACK’S SEASON TWO COSTUME. Jack’s blue jeans, blue t-shirt and shoes worn in Season Two. $200 – $300 219. JACK’S SEASON TWO COSTUME. Jack’s blue jeans and green t-shirt worn in Season Two. $200 – $300 220. JACK’S SEASON TWO COS- TUME. Jack’s blue jeans and gray t-shirt worn in Season Two. $200 – $300 222. JACK’S MEDICAL BAG. Dark brown leather shoulder bag used by Jack in Season Two to carry medical supplies. $200 – $300 71 www.liveauctioneers.com LOST | The Auction 225. KATE’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “WHAT KATE DID.” Kate’s brown corduroy pants, brown print t-shirt, and jean jacket worn in the episode, “What Kate Did.” $200 – $300 223. KATE’S SEASON TWO ISLAND COS- TUME. Kate’s white tank top, beige long- sleeve shirt and brown corduroy cargo pants worn in Season Two. $200 – $300 224. KATE’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “WHAT KATE DID.” Kate’s jeans, jean jacket and Janis Joplin print shirt worn in the episode, “What Kate Did.” $200 – $300 226. HURLEY’S SEASON TWO COSTUMES. Hurley’s olive green shorts and red t- shirt worn on the Island in the episode, “S.O.S..” Includes Hurley’s black jeans, gray t-shirt and black hoodie worn in Season Two. $200 – $300 72 1-310-859-7701 Profiles in History | August 21 & 22, 2010 227. HURLEY’S MR. CLUCK’S CHICKEN SHACK COSTUME. Hurley’s black pants, green Mr. -

10 Lost Wanted

Wanted updated 03-12-13 LOST Season 1 Missing: Oceanic 815 Puzzle Cards (1:11 packs) M1 Charlie: Get it? Hurley: Dude, quit asking me Walkabout M3 Claire: I'm having contractions. Jack: How man Pilot Pt. 1 M4 Jack: Come on. Come on! Come on! Come on! Big Pilot Pt. 1 M5 Jack: We must have been at about forth thousan Pilot Pt. 1 M6 Michael: Hey, hey, where you going, man? Walt: Walkabout M7 Charlie: How does something like that happen? Pilot Pt. 1 M8 Pilot: Six hours in, our radio went out. No on Pilot Pt. 1 M9 Kate: Jack! Jack: There's someone else still o White Rabbit Numbers Die-Cut Cards (1:17 packs) 15 Sawyer: That what I think it is? Michael: Some Exodus, Pt. 2 23 Kate: I wanted you to make sure that Ray Mulle Tabula Rasa 42 Hurley: ...Stop! What are you doing?! Why'd yo Exodus, Pt. 2 Autograph Cards (1:36 packs) A-1 Evangeline Lilly as Kate Austen A-2 Josh Holloway as James "Sawyer" Ford A-3 Maggie Grace as Shannon Rutherford A-5 Mira Furlan as Danielle Rousseau A-6 William Mapother as Ethan Rom A-7 John Terry as Dr. Christian Shephard A-9 Daniel Roebuck as Dr. Leslie Arzt A-11 Kevin Tighe as Anthony Cooper A-12 Swoosie Kurtz as Emily Annabeth Locke AR1 (Redemption Card) Pieceworks Cards (1:36 packs) PW-1 Shirt worn by Evangeline Lilly as Kate Austen The Greater Good PW-2 T-shirt worn by Josh Holloway as Sawyer Ford Pilot PW-3 Top worn by Maggie Grace as Shannon Rutherford Hearts and Minds PW-4 T-shirt worn by Matthew Fox as Jack Shepherd All the Best Cowboys Have Daddy Issues PW-5 T-shirt worn by Dominic Monaghan as Charlie Pace Pilot PW-6 T-shirt worn by Terry O'Quinn as John Locke Numbers PW-8 T-shirt worn by Jorge Garcia as Hugo "Hurley" Reyes Hearts and Mind PW-10 Top worn by Yunjin Kim as Sun Kwon Exodus Pt. -

The Etiology of Character Realization, Within Rhetorical Analysis of the Series

i Found: The Etiology of Character Realization, within Rhetorical Analysis of the Series LOST, through the Application of Underhill’s and Turner’s Classic Concepts of the Mystic Journey ____________________________________________ Presented to the Faculty Liberty University School of Communication Studies ______________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in Communication By Lacey L. Mitchell 2 December 2010 ii Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in Communication Studies Michael P. Graves Ph.D., Chair Carey Martin Ph.D., Reader Todd Smith M.F.A, Reader iii Dedication For James and Mildred Renfroe, and Donald, Kim and Chase Mitchell, without whom this work would have been remiss. I am forever grateful for your constant, unwavering support, exemplary resolve, and undiscouraged love. iv Acknowledgements This work represents the culmination of a remarkable journey in my life. Therefore, it is paramount that I recognize several individuals I found to be indispensible. First, I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Michael Graves, for taking this process and allowing it to be a learning and growing experience in my own journey, providing me with unconventional insight, and patiently answering my never ending list of inquiries. His support through this process pushed me towards a completed work – Thank you. I also owe a great debt to the readers on my committee, Dr. Cary Martin and Todd Smith, who took time to ensure the completion of the final product. I will always have immense gratitude for my family. Each of them has an incredible work ethic and drive for life that constantly pushes me one step further. -

The Vilcek Foundation Celebrates a Showcase Of

THE VILCEK FOUNDATION CELEBRATES A SHOWCASE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS AND FILMMAKERS OF ABC’S HIT SHOW EXHIBITION CATALOGUE BY EDITH JOHNSON Exhibition Catalogue is available for reference inside the gallery only. A PDF version is available by email upon request. Props are listed in the Exhibition Catalogue in the order of their appearance on the television series. CONTENTS 1 Sun’s Twinset 2 34 Two of Sun’s “Paik Industries” Business Cards 22 2 Charlie’s “DS” Drive Shaft Ring 2 35 Juliet’s DHARMA Rum Bottle 23 3 Walt’s Spanish-Version Flash Comic Book 3 36 Frozen Half Wheel 23 4 Sawyer’s Letter 4 37 Dr. Marvin Candle’s Hard Hat 24 5 Hurley’s Portable CD/MP3 Player 4 38 “Jughead” Bomb (Dismantled) 24 6 Boarding Passes for Oceanic Airlines Flight 815 5 39 Two Hieroglyphic Wall Panels from the Temple 25 7 Sayid’s Photo of Nadia 5 40 Locke’s Suicide Note 25 8 Sawyer’s Copy of Watership Down 6 41 Boarding Passes for Ajira Airways Flight 316 26 9 Rousseau’s Music Box 6 42 DHARMA Security Shirt 26 10 Hatch Door 7 43 DHARMA Initiative 1977 New Recruits Photograph 27 11 Kate’s Prized Toy Airplane 7 44 DHARMA Sub Ops Jumpsuit 28 12 Hurley’s Winning Lottery Ticket 8 45 Plutonium Core of “Jughead” (and sling) 28 13 Hurley’s Game of “Connect Four” 9 46 Dogen’s Costume 29 14 Sawyer’s Reading Glasses 10 47 John Bartley, Cinematographer 30 15 Four Virgin Mary Statuettes Containing Heroin 48 Roland Sanchez, Costume Designer 30 (Three intact, one broken) 10 49 Ken Leung, “Miles Straume” 30 16 Ship Mast of the Black Rock 11 50 Torry Tukuafu, Steady Cam Operator 30 17 Wine Bottle with Messages from the Survivor 12 51 Jack Bender, Director 31 18 Locke’s Hunting Knife and Sheath 12 52 Claudia Cox, Stand-In, “Kate 31 19 Hatch Painting 13 53 Jorge Garcia, “Hugo ‘Hurley’ Reyes” 31 20 DHARMA Initiative Food & Beverages 13 54 Nestor Carbonell, “Richard Alpert” 31 21 Apollo Candy Bars 14 55 Miki Yasufuku, Key Assistant Locations Manager 32 22 Dr.