LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Press Release

Elisabeth Moss as Peggy Olson Outstanding Lead Actor In A Drama Series Nashville • ABC • ABC Studios Connie Britton as Rayna James Breaking Bad • AMC • Sony Pictures Television Scandal • ABC • ABC Studios Bryan Cranston as Walter White Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope Downton Abbey • PBS • A Carnival / Masterpiece Co-Production Hugh Bonneville as Robert, Earl of Grantham Outstanding Lead Actor In A Homeland • Showtime • Showtime Presents, Miniseries Or A Movie Teakwood Lane Productions, Cherry Pie Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Keshet, Fox 21 Weintraub Productions in association with Damian Lewis as Nicholas Brody HBO Films House Of Cards • Netflix • Michael Douglas as Liberace Donen/Fincher/Roth and Trigger Street Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Inc. in association with Media Weintraub Productions in association with Rights Capital for Netflix HBO Films Kevin Spacey as Francis Underwood Matt Damon as Scott Thorson Mad Men • AMC • Lionsgate Television The Girl • HBO • Warner Bros. Jon Hamm as Don Draper Entertainment, GmbH/Moonlighting and BBC in association with HBO Films and Wall to The Newsroom • HBO • HBO Entertainment Wall Media Jeff Daniels as Will McAvoy Toby Jones as Alfred Hitchcock Parade's End • HBO • A Mammoth Screen Production, Trademark Films, BBC Outstanding Lead Actress In A Worldwide and Lookout Point in association Drama Series with HBO Miniseries and the BBC Benedict Cumberbatch as Christopher Tietjens Bates Motel • A&E • Universal Television, Carlton Cuse Productions and Kerry Ehrin -

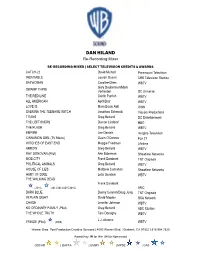

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer

DAN HILAND Re-Recording Mixer RE-RECORDING MIXER | SELECT TELEVISION CREDITS & AWARDS CATCH-22 David Michod Paramount Television INSATIABLE Lauren Gussis CBS Television Studios BATWOMAN Caroline Dries WBTV Gary Dauberman/Mark SWAMP THING Verheiden DC Universe THE RED LINE Cairlin Parrish WBTV ALL AMERICAN April Blair WBTV LOVE IS Mara Brock Akil OWN SABRINA THE TEENAGE WITCH Jonathan Schmock Viacom Productions TITANS Greg Berlanti DC Entertainment THE LEFTOVERS Damon Lindelof HBO THE FLASH Greg Berlanti WBTV EMPIRE Lee Daniels Imagine Television CINNAMON GIRL (TV Movie) Gavin O'Connor Fox 21 WITCHES OF EAST END Maggie Friedman Lifetime ARROW Greg Berlanti WBTV RAY DONOVAN (Pilot) Ann Biderman Showtime Networks MOB CITY Frank Darabont TNT Originals POLITICAL ANIMALS Greg Berlanti WBTV HOUSE OF LIES Matthew Carnahan Showtime Networks HART OF DIXIE Leila Gerstein WBTV THE WALKING DEAD Frank Darabont (2010) (2012/2014/2015/2016) AMC DARK BLUE Danny Cannon/Doug Jung TNT Originals IN PLAIN SIGHT David Maples USA Network CHASE Jennifer Johnson WBTV NO ORDINARY FAMILY (Pilot) Greg Berlanti ABC Studios THE WHOLE TRUTH Tom Donaghy WBTV J.J. Abrams FRINGE (Pilot) (2009) WBTV Warner Bros. Post Production Creative Services | 4000 Warner Blvd. | Burbank, CA 91522 | 818.954.7825 Award Key: W for Win | N for Nominated OSCAR | BAFTA | EMMY | MPSE | CAS LIMELIGHT (Pilot) David Semel, WBTV HUMAN TARGET Jonathan E. Steinberg WBTV EASTWICK Maggie Friedman WBTV V (Pilot) Kenneth Johnson WBTV TERMINATOR: THE SARAH CONNER Josh Friedman CHRONICLES WBTV CAPTAIN -

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Henley's the Wake of Jamie Foster and the Miss Firecracker Contest

‘SNOW BRIDE’ CAST BIOS PATRICIA RICHARDSON (Maggie Tannenhill) – Patricia Richardson is best known for her portrayal of Jill Taylor on the long running series “Home Improvement” in which she co-starred with Tim Allen. For her work on the series, she received four Emmy® nominations and two Golden Globe® nominations as Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series. While performing in “Home Improvement,” she also co-hosted the Emmy® Awards with Ellen DeGeneres. In 2009, the cast members of “Home Improvement” received a Fan Favorite Award from the TV Land Awards. She has also received a Vision Award and a Women In Film Award in Texas and commendations from the Prism Awards for her work in the show. For two years, she had a recurring role in “The West Wing” as Sheila Brooks, Sen. Arnold Vinick’s (Alan Alda) chief of staff. She was nominated for an Independent Spirit Award for her role in “Ulee’s Gold,” opposite Peter Fonda and directed by Victor Nunez. Previously, Richardson garnered rave reviews for her portrayal of Marilyn Monroe’s mother in the CBS miniseries “Blonde.” She played twins in “Viva Las Nowhere,” co-starring Danny Stern and James Caan, which was released on video under the title “Dead Simple” and won a Seattle Film Festival Award. She received more great reviews for her role in Lifetime’s “Sophie & the Moonhanger,” co-starring Lynn Whitfield and Jason Bernard and “Undue Influence,” with Brian Dennehy. Other films include “Lost Angels,” “In Country” and “Beautiful Wave.” She was brought out to Los Angeles from New York after several years of doing theater, first by Norman Lear and then Alan Burns, to do three different series prior to “Home Improvement” - “Double Trouble” for Lear and then “Eisenhower and Lutz” and “FM” for Burns. -

LOST with a Good Book

The Lost Code: BYYJ C`1 P,YJ- LJ,1 Key Literary References and Influ- Books, Movies, and More on Your Favorite Subjects Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad CAS A CONR/ eAudiobook LOST on DVD A man journeys through the Congo and Lost Complete First Season contemplates the nature of good and evil. There are several references, especially in relation to Lost Season 2: Extended Experience Colonel’s Kurtz’s descent toward madness. Lost Season 3: The Unexplored Experience Lost. The Complete Fourth Season: The Expanded The Stand by Stephen King FIC KING Experience A battle between good and evil ensues after a deadly virus With a Good Book decimates the population. Producers cite this book as a Lost. The Complete Fifth Season: The Journey Back major influence, and other King allusions ( Carrie , On Writing , *Lost: Complete Sixth & Final Season is due for release 8/24/10. The Shining , Dark Tower series, etc.) pop up frequently. The Odyssey by Homer FIC HOME/883 HOME/ CD BOOK 883.1 HOME/CAS A HOME/ eAudiobook LOST Episode Guide Greek epic about Odysseus’s harrowing journey home to his In addition to the biblical episode titles, there are several other Lost wife Penelope after the Trojan War. Parallels abound, episode titles with literature/philosophy connections. These include “White especially in the characters of Desmond and Penny. Rabbit” and “Through the Looking Glass” from Carroll’s Alice books; “Catch-22”; “Tabula Rosa” (philosopher John Locke’s theory that the Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut FIC VON human mind is a blank slate at birth); and “The Man Behind the Curtain” A World War II soldier becomes “unstuck in time,” and is and “There’s No Place Like Home” ( The Wonderful Wizard of Oz ). -

The MULLET RAPPER What’S Happening in the Everglades City Area TIDE TABLE 25¢ RESTAURANTS JAN

The MULLET RAPPER What’s Happening in the Everglades City Area TIDE TABLE 25¢ RESTAURANTS JAN. 28 – FEB. 10, 2017 \ © 2017, K Bee Marketing P O Box 134, Everglades City, FL, 34139 Volume X Issue #281 Art-In-The-Glades Events 2017 Everglades Seafood Festival Schedule of Events! Combine Local Art & Entertainment It’s that time of year again! The annual Everglades Seafood Festival If you have not been to one of the Art- will roll into town for the weekend on Friday February 10th through In-The-Glades events, you’re missing Sunday the 12th. You can expect great foods, unique art, crafts and jewelry out! Local Artists, musicians and and carnival rides for the kids. Music is always a feature, and this year won’t disappoint. Mark your calendars and book your rooms so you don’t miss one day of this great event. Mayor Hamilton greets the crowd in 2016 EVERGLADES SEAFOOD FESTIVAL - 2017 LINEUP Friday, February 10 5:30 pm OPENING CEREMONY 5:45 pm Charlie Pace entrepreneurs have made this a “must 6:30 pm The Lost Rodeo attend” for area residents and visitors. 7:30 pm Let's Hang On Booths are free so be sure to sign up for 9:00 pm Chappell & Chet the next event taking place on Feb. 25th! 9:45 pm Tim Elliott For info call Marya @ 239-695-2905, for more details, see page 3. Saturday, February 11 There is something for everyone to enjoy 10:00 am OPENING CEREMONY National Anthem - Sloan Wheeler 11:00 am Delbert Britton/Ronnie Goff and the Country Hustlers 12:00 pm Them Hamilton Boys 1:00 pm Gator Nate 2:00 pm Garrett Speer 3:15 pm A Thousand Horses 5:30 pm Tim Charron 7:00 pm Tim Elliott 8:30 pm Little Texas Sunday, February 12 11:00 am OPENING CEREMONY Rides for the kids or the “kid in you” National Anthem - Nadia Turner RAPPER TABLE OF CONTENTS 12:00 pm Tim McGeary Calendar p. -

LOST "Raised by Another" (YELLOW) 9/23/04

LOST “Raised by Another” CAST LIST BOONE................................Ian Somerhalder CHARLIE..............................Dominic Monaghan CLAIRE...............................Emilie de Ravin HURLEY...............................Jorge Garcia JACK.................................Matthew Fox JIN..................................Daniel Dae Kim KATE.................................Evangeline Lilly LOCKE................................Terry O’Quinn MICHAEL..............................Harold Perrineau SAWYER...............................Josh Holloway SAYID................................Naveen Andrews SHANNON..............................Maggie Grace SUN..................................Yunjin Kim WALT.................................Malcolm David Kelley THOMAS............................... RACHEL............................... MALKIN............................... ETHAN................................ SLAVITT.............................. ARLENE............................... SCOTT................................ * STEVE................................ * www.pressexecute.com LOST "Raised by Another" (YELLOW) 9/23/04 LOST “Raised by Another” SET LIST INTERIORS THE VALLEY - Late Afternoon/Sunset CLAIRE’S CUBBY - Night/Dusk/Day ENTRANCE * ROCK WALL - Dusk/Night/Day * INFIRMARY CAVE - Morning JACK’S CAVE - Night * LOFT - Day - FLASHBACK MALKIN’S HOUSE - Day - FLASHBACK BEDROOM - Night - FLASHBACK LAW OFFICES CONFERENCE ROOM - Day - FLASHBACK EXTERIORS JUNGLE - Night/Day ELSEWHERE - Day CLEARING - Day BEACH - Day OPEN JUNGLE - Morning * SAWYER’S -

The Culture of Wikipedia

Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia Good Faith Collaboration The Culture of Wikipedia Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. Foreword by Lawrence Lessig The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Web edition, Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. CC-NC-SA 3.0 Purchase at Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble | IndieBound | MIT Press Wikipedia's style of collaborative production has been lauded, lambasted, and satirized. Despite unease over its implications for the character (and quality) of knowledge, Wikipedia has brought us closer than ever to a realization of the centuries-old Author Bio & Research Blog pursuit of a universal encyclopedia. Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia is a rich ethnographic portrayal of Wikipedia's historical roots, collaborative culture, and much debated legacy. Foreword Preface to the Web Edition Praise for Good Faith Collaboration Preface Extended Table of Contents "Reagle offers a compelling case that Wikipedia's most fascinating and unprecedented aspect isn't the encyclopedia itself — rather, it's the collaborative culture that underpins it: brawling, self-reflexive, funny, serious, and full-tilt committed to the 1. Nazis and Norms project, even if it means setting aside personal differences. Reagle's position as a scholar and a member of the community 2. The Pursuit of the Universal makes him uniquely situated to describe this culture." —Cory Doctorow , Boing Boing Encyclopedia "Reagle provides ample data regarding the everyday practices and cultural norms of the community which collaborates to 3. Good Faith Collaboration produce Wikipedia. His rich research and nuanced appreciation of the complexities of cultural digital media research are 4. The Puzzle of Openness well presented. -

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space With

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space with Flashbacks and Flash-forwards in the Series "Lost" Promotor: Auteur: Prof. Dr. S. Slembrouck Olga Berendeeva Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Afstudeerrichting: Master Engels Academiejaar 2008-2009 2e examenperiode For My Parents Who are so far But always so close to me Мои родителям, Которые так далеко, Но всегда рядом ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Stefaan Slembrouck for his interest in my work. I am grateful for all the encouragement, help and ideas he gave me throughout the writing. He was the one who helped me to figure out the subject of my work which I am especially thankful for as it has been such a pleasure working on it! Secondly, I want to thank my boyfriend Patrick who shared enthusiasm for my subject, inspired me, and always encouraged me to keep up even when my mood was down. Also my friend Sarah who gave me a feedback on my thesis was a very big help and I am grateful. A special thank you goes to my parents who always believed in me and supported me. Thanks to all the teachers and professors who provided me with the necessary baggage of knowledge which I will now proudly carry through life. iii Foreword In my previous research paper I wrote about film discourse, thus, this time I wanted to continue with it but have something new, some kind of challenge which would interest me. After a conversation with my thesis guide, Professor Slembrouck, we decided to stick on to film discourse but to expand it. -

Maital Sabban Make-Up Artist

6356 W. 6th Street • Los Angeles, CA 90048 • Phone 323.935.8455 • Fax 323.935.3143 MAITAL SABBAN MAKE-UP ARTIST DIRECTORS & PHOTOGRAPHERS: Alberto Tolot David La Chapelle Kevin Kerslake Allan Fis David Steinberg Kieran Walsh Anastacia & Ian David Tsay Kinka Usher Andrew McPherson Davis Factor Larson & Talbert Andrew Southam Dick Buckley Lauren Greenfield Andy Morahan Dominique Guillemont Lita Wilson Angela Alvarado Rosa Eika Aoshima Lorenzo Agius Angelina Venturella Emily Shur Mark Anderson Anghel Decca Fatima Mark Seliger Annie Leibovitz Francis Lawrence Martin Scholler Anouk Besson Frank Samuels Mary Ellen Mark Anthea Benton Gavin Bond Matthew Rolston Anthony Mandler Geoff Moore Meirt Avis Arnold Turner Giuliano Bekor Memo del Bosque Art Streiber Graham Michael Martin Blake Little Gustavo Garzon Michael Muller Bob Giraldi Helmut Newton Michel Gondry Brian Bowen Smith Henman Mike Ruiz Cam Archer Herb Ritts Miranda Penn Turin Carl Rinsch Jack Guy Moshe Brakha Charles Jensen James Houston Nancy Bardawil Chris Applebaum Jeff Berlin Nigel Dick Chris Floyd Jeff Katz Noriyuki Tanaka Chris Fortuna Jeff Lipsky Norman Jean Roy Chris McPherson Jeremy Goldberg Omar Cruz Christopher Beyer Jerry Avenaim Pablo Alfaro Christy Bush Jim Gable Patrick Anderson Craid De Cristo Jim Wright Patrick Demarchelier Craig Cutler John Russo Paul Hunter Danny Ducovny Joseph Kahn Randall Mesdon David Hogan Joseph Murray Randee St. Nicholas David Kellogg Joseph Pluchino Rankin 6356 W. 6th Street • Los Angeles, CA 90048 • Phone 323.935.8455 • Fax 323.935.3143 MAITAL SABBAN MAKE-UP ARTIST (CONT’D.) DIRECTORS & PHOTOGRAPHERS (CONT’D.): Rent Sidon Stephan Kyndt Tom Gatsoulis Richard McLaren Steve Ramser Tony Duran Robert Ascroft Steve Shaw Traktor Robert Fleischauer Steven Lippman Wayne Isham Robert Rodriguez Steven Ziegler Walter Iooss Roger Erickson Stylewar Willie Maldonado Sheryl Nield The Malloy Bros. -

Copyrighted Material

PART ON E F IS FOR FORTUNE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL CCH001.inddH001.indd 7 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM CCH001.inddH001.indd 8 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM LOST IN LOST ’ S TIMES Richard Davies Lost and Losties have a pretty bad reputation: they seem to get too much fun out of telling and talking about stories that everyone else fi nds just irritating. Even the Onion treats us like a bunch of fanatics. Is this fair? I want to argue that it isn ’ t. Even if there are serious problems with some of the plot devices that Lost makes use of, these needn ’ t spoil the enjoyment of anyone who fi nds the series fascinating. Losing the Plot After airing only a few episodes of the third season of Lost in late 2007, the Italian TV channel Rai Due canceled the show. Apparently, ratings were falling because viewers were having diffi culty following the plot. Rai Due eventually resumed broadcasting, but only after airing The Lost Survivor Guide , which recounts the key moments of the fi rst two seasons and gives a bit of background on the making of the series. Even though I was an enthusiastic Lostie from the start, I was grateful for the Guide , if only because it reassured me 9 CCH001.inddH001.indd 9 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM 10 RICHARD DAVIES that I wasn’ t the only one having trouble keeping track of who was who and who had done what.