Existential Analytics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space With

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space with Flashbacks and Flash-forwards in the Series "Lost" Promotor: Auteur: Prof. Dr. S. Slembrouck Olga Berendeeva Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Afstudeerrichting: Master Engels Academiejaar 2008-2009 2e examenperiode For My Parents Who are so far But always so close to me Мои родителям, Которые так далеко, Но всегда рядом ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Stefaan Slembrouck for his interest in my work. I am grateful for all the encouragement, help and ideas he gave me throughout the writing. He was the one who helped me to figure out the subject of my work which I am especially thankful for as it has been such a pleasure working on it! Secondly, I want to thank my boyfriend Patrick who shared enthusiasm for my subject, inspired me, and always encouraged me to keep up even when my mood was down. Also my friend Sarah who gave me a feedback on my thesis was a very big help and I am grateful. A special thank you goes to my parents who always believed in me and supported me. Thanks to all the teachers and professors who provided me with the necessary baggage of knowledge which I will now proudly carry through life. iii Foreword In my previous research paper I wrote about film discourse, thus, this time I wanted to continue with it but have something new, some kind of challenge which would interest me. After a conversation with my thesis guide, Professor Slembrouck, we decided to stick on to film discourse but to expand it. -

LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy

"Accidental Intellectuals": LOST Fandom and Everyday Philosophy Author: Abigail Letak Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/2615 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2012 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! This thesis is dedicated to everyone who has ever been obsessed with a television show. Everyone who knows that adrenaline rush you get when you just can’t stop watching. Here’s to finding yourself laughing and crying along with the characters. But most importantly, here’s to shows that give us a break from the day-to-day milieu and allow us to think about the profound, important questions of life. May many shows give us this opportunity as Lost has. Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to thank my parents, Steve and Jody, for their love and support as I pursued my area of interest. Without them, I would not find myself where I am now. I would like to thank my advisor, Juliet Schor, for her immense help and patience as I embarked on combining my personal interests with my academic pursuits. Her guidance in methodology, searching the literature, and general theory proved invaluable to the completion of my project. I would like to thank everyone else who has provided support for me throughout the process of this project—my friends, my professors, and the Presidential Scholars Program. I’d like to thank Professor Susan Michalczyk for her unending support and for believing in me even before I embarked on my four years at Boston College, and for being the one to initially point me in the direction of sociology. -

Post/Teca 03.2011

Post/teca materiali digitali a cura di sergio failla 03.2011 ZeroBook 2011 Post/teca materiali digitali Di post in post, tutta la vita è un post? Tra il dire e il fare c'è di mezzo un post? Meglio un post oggi che niente domani? E un post è davvero un apostrofo rosa tra le parole “hai rotto er cazzo”? Questi e altri quesiti potrebbero sorgere leggendo questa antologia di brani tratti dal web, a esclusivo uso e consumo personale e dunque senza nessunissima finalità se non quella di perder tempo nel web. (Perché il web, Internet e il computer è solo questo: un ennesimo modo per tutti noi di impiegare/ perdere/ investire/ godere/ sperperare tempo della nostra vita). In massima parte sono brevi post, ogni tanto qualche articolo. Nel complesso dovrebbero servire da documentazione, zibaldone, archivio digitale. Per cosa? Beh, questo proprio non sta a me dirlo. Buona parte del materiale qui raccolto è stato ribloggato anche su girodivite.tumblr.com grazie al sistema di re-blog che è possibile con il sistema di Tumblr. Altro materiale qui presente è invece preso da altri siti web e pubblicazioni online e riflette gli interessi e le curiosità (anche solo passeggeri e superficiali) del curatore. Questo archivio esce diviso in mensilità. Per ogni “numero” si conta di far uscire la versione solo di testi e quella fatta di testi e di immagini. Quanto ai copyright, beh questa antologia non persegue finalità commerciali, si è sempre cercato di preservare la “fonte” o quantomeno la mediazione (“via”) di ogni singolo brano. Qualcuno da qualche parte ha detto: importa certo da dove proviene una cosa, ma più importante è fino a dove tu porti quella cosa. -

The Vilcek Foundation Celebrates a Showcase Of

THE VILCEK FOUNDATION CELEBRATES A SHOWCASE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS AND FILMMAKERS OF ABC’S HIT SHOW EXHIBITION CATALOGUE BY EDITH JOHNSON Exhibition Catalogue is available for reference inside the gallery only. A PDF version is available by email upon request. Props are listed in the Exhibition Catalogue in the order of their appearance on the television series. CONTENTS 1 Sun’s Twinset 2 34 Two of Sun’s “Paik Industries” Business Cards 22 2 Charlie’s “DS” Drive Shaft Ring 2 35 Juliet’s DHARMA Rum Bottle 23 3 Walt’s Spanish-Version Flash Comic Book 3 36 Frozen Half Wheel 23 4 Sawyer’s Letter 4 37 Dr. Marvin Candle’s Hard Hat 24 5 Hurley’s Portable CD/MP3 Player 4 38 “Jughead” Bomb (Dismantled) 24 6 Boarding Passes for Oceanic Airlines Flight 815 5 39 Two Hieroglyphic Wall Panels from the Temple 25 7 Sayid’s Photo of Nadia 5 40 Locke’s Suicide Note 25 8 Sawyer’s Copy of Watership Down 6 41 Boarding Passes for Ajira Airways Flight 316 26 9 Rousseau’s Music Box 6 42 DHARMA Security Shirt 26 10 Hatch Door 7 43 DHARMA Initiative 1977 New Recruits Photograph 27 11 Kate’s Prized Toy Airplane 7 44 DHARMA Sub Ops Jumpsuit 28 12 Hurley’s Winning Lottery Ticket 8 45 Plutonium Core of “Jughead” (and sling) 28 13 Hurley’s Game of “Connect Four” 9 46 Dogen’s Costume 29 14 Sawyer’s Reading Glasses 10 47 John Bartley, Cinematographer 30 15 Four Virgin Mary Statuettes Containing Heroin 48 Roland Sanchez, Costume Designer 30 (Three intact, one broken) 10 49 Ken Leung, “Miles Straume” 30 16 Ship Mast of the Black Rock 11 50 Torry Tukuafu, Steady Cam Operator 30 17 Wine Bottle with Messages from the Survivor 12 51 Jack Bender, Director 31 18 Locke’s Hunting Knife and Sheath 12 52 Claudia Cox, Stand-In, “Kate 31 19 Hatch Painting 13 53 Jorge Garcia, “Hugo ‘Hurley’ Reyes” 31 20 DHARMA Initiative Food & Beverages 13 54 Nestor Carbonell, “Richard Alpert” 31 21 Apollo Candy Bars 14 55 Miki Yasufuku, Key Assistant Locations Manager 32 22 Dr. -

Network Fictions Article

Research How to Cite: Mousoutzanis, A 2016 Network Fictions and the Global Unhomely. C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings, 4(1): 7, pp. 1–19, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16995/c21.7 Published: 18 April 2016 Peer Review: This article has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of C21 Literature: Journal of 21st- century Writings, which is a journal of the Open Library of Humanities. Copyright: © 2016 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distri- bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Open Access: C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings is a peer-reviewed open access journal. Digital Preservation: The Open Library of Humanities and all its journals are digitally preserved in the CLOCKSS scholarly archive service. The Open Library of Humanities is an open access non-proft publisher of scholarly articles and monographs. Aris Mousoutzanis, ‘Network Fictions and the Global Unhomely’ (2016) 4(1): 7 C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-century Writings, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16995/c21.7 RESEARCH Network Fictions and the Global Unhomely Aris Mousoutzanis1 1 University of Brighton, GB [email protected] The paper suggests that the increasing proliferation of network fctions in literature, flm, television and the internet may be interpreted through a theoretical framework that reconceptuallises the originally strictly psychoanalytic concept of the Unheimlich (Freud’s idea of the ‘unhomely’ or ‘uncanny’) within the context of political, economic and cultural disources fo globalisation. -

Magazine Media

SEPTEMBER 2009: DRAMA MM M M MediaMagazine edia agazine Menglish and media centre issue 29 | septemberM 2009 Reading Red Riding Bond and beyond Learning to Tweet Representations in TV drama Drama in the news english and media centre andmedia english The webisode story 2009 |september 29 ssue | i MM MM MediaMagazine is published by the English and Media Centre, a non-profit making organisation. editorial The Centre publishes a wide range of classroom materials and runs For those of you just starting out, welcome to the wonderful courses for teachers. If you’re world of Film and Media Studies; for those of you returning for studying English at A Level, look out an A2 year, welcome back, hopefully with the results you wanted; for emagazine, also published by and for everyone, welcome to the first of this year’s editions of the Centre. MediaMagazine. The English and Media Centre This issue explores the theme of Drama from a wide range of 18 Compton Terrace perspectives. Starting with the basics, Mark Ramey considers the London N1 2UN differences between the experiences of theatre and cinema, and asks what makes a Telephone: 020 7359 8080 drama cinematic, while Nick Lacey explores some of the essential differences – and Fax: 020 7354 0133 similarities – between the big and small screen with a study of State of Play from Email for subscription enquiries: TV drama to Hollywood blockbuster. Stephen Hill takes a historical approach to the [email protected] development of TV drama in its social and historical context, and demonstrates its Managing Editor: Michael Simons changing technologies and representations through analysis of Mike Leigh’s iconic 70s comedy of manners Abigail’s Party. -

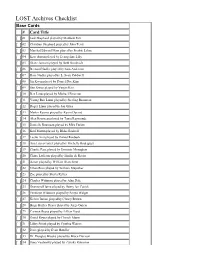

LOST Archives Checklist

LOST Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Jack Shephard played by Matthew Fox [ ] 02 Christian Shephard played by John Terry [ ] 03 Marshal Edward Mars played by Fredric Lehne [ ] 04 Kate Austin played by Evangeline Lilly [ ] 05 Diane Janssen played by Beth Broderick [ ] 06 Bernard Nadler played by Sam Anderson [ ] 07 Rose Nadler played by L. Scott Caldwell [ ] 08 Jin Kwon played by Daniel Dae Kim [ ] 09 Sun Kwon played by Yunjin Kim [ ] 10 Ben Linus played by Michael Emerson [ ] 11 Young Ben Linus played by Sterling Beaumon [ ] 12 Roger Linus played by Jon Gries [ ] 13 Martin Keamy played by Kevin Durand [ ] 14 Alex Rousseau played by Tania Raymonde [ ] 15 Danielle Rousseau played by Mira Furlan [ ] 16 Karl Martin played by Blake Bashoff [ ] 17 Leslie Arzt played by Daniel Roebuck [ ] 18 Ana Lucia Cortez played by Michelle Rodriguez [ ] 19 Charlie Pace played by Dominic Monaghan [ ] 20 Claire Littleton played by Emilie de Ravin [ ] 21 Aaron played by William Blanchette [ ] 22 Ethan Rom played by William Mapother [ ] 23 Zoe played by Sheila Kelley [ ] 24 Charles Widmore played by Alan Dale [ ] 25 Desmond Hume played by Henry Ian Cusick [ ] 26 Penelope Widmore played by Sonya Walger [ ] 27 Kelvin Inman played by Clancy Brown [ ] 28 Hugo Hurley Reyes played by Jorge Garcia [ ] 29 Carmen Reyes played by Lillian Hurst [ ] 30 David Reyes played by Cheech Marin [ ] 31 Libby Smith played by Cynthia Watros [ ] 32 Dave played by Evan Handler [ ] 33 Dr. Douglas Brooks played by Bruce Davison [ ] 34 Ilana Verdansky played by Zuleika -

TV/Series, Hors Séries 1 | 2016 the Promise of Lost (About Season 2) 2

TV/Series Hors séries 1 | 2016 Lost: (re)garder l'île The Promise of Lost (About Season 2) Guillaume Dulong Translator: Brian Stacy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/4963 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.4963 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Guillaume Dulong, « The Promise of Lost (About Season 2) », TV/Series [Online], Hors séries 1 | 2016, Online since 01 December 2020, connection on 05 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/tvseries/4963 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/tvseries.4963 This text was automatically generated on 5 December 2020. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. The Promise of Lost (About Season 2) 1 The Promise of Lost (About Season 2) Guillaume Dulong Translation : Brian Stacy I am like a man who, having grounded his ship on many shoals and nearly wrecked it in passing a small island, still has the nerve to put out to sea in the same leaky weather-beaten vessel, and even carries his ambition so far as to think of going around the globe in it. My memory of past errors and perplexities makes me unsure about the future. The wretched condition, the weakness and disorder, of the ·intellectual· faculties that I have to employ in my enquiries increase my anxiety. And the impossibility of amending or correcting these faculties reduces me almost to despair, and makes me resolve to die on the barren rock where I am now rather than to venture into that boundless ocean that goes on to infinity1! 1 After Lost's first season ended with a hit finale that saw its characters blast open the hatch, the stakes involved in writing the sequel were so high that Cuse and Lindelof were quoted saying that Abrams came forward right away to ask them what was beneath the hatch. -

The Lost Pdf Free Download

THE LOST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J. D. Robb | 373 pages | 10 Oct 2014 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780515147186 | English | New York, United States The Lost PDF Book Mar 11, Carrie brightbeautifulthings rated it liked it Shelves: netgalley , ya-realism , horrorshow. And to make matters worse Piper starts falling for the random dude who shows up weeks later claiming his been kept away in a separate room for the last six months? I also did not establish a connection to any of the characters. I would have gotten 5 stars but the ending is way to open. Here are the 10 Best Books of , along with Notable Books of the year. Like some mythical hero who pays a visit to that realm of shadows the Greeks called the underworld, Mendelsohn has brought back stories of the dead that we are not likely to forget long after we close his book. She's known this guy for years and he's never given her the time of day. External Reviews. This being said I hated the end. It ends in a cliffhanger and I wish she would have kept the story going or ended the book where Piper gets home to her parents instead of Evan taking her. But Mendelsohn has tried to do other things here as well, such as show how memory and truth can converge and diverge at the flick of an eyelid, and that, despite what seems to be long runs of coincidences in his journeying towards finding the story…This is a great achievement, and an intensely moving one. -

"Man of Science, Man of Faith:" Lost, Consumer Agency and the Fate

"Man of Science, Man of Faith:" Lost, Consumer Agency and the Fate/Free Will Binary in the Post-9/tt Context Susan Tkachuk Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Intersdisciplinary Master of Arts in Popular Culture Brock University © Susan Tkachuk, June 2009 Abstract In 2004, Lost debuted on ABC and quickly became a cultural phenomenon. Its postmodem take on the classic Robinson Crusoe desert island scenario gestures to a variety of different issues circulating within the post-9II1 cultural consciousness, such as terrorism, leadership, anxieties involving air travel, torture, and globalization. Lost's complex interwoven flashback and flash-forward narrative structure encourages spectators to creatively hypothesize solutions to the central mysteries of the narrative, while also thematically addressing archetypal questions of freedom of choice versus fate. Through an examination of the narrative structure, the significance of technological shifts in television, and fan cultures in Lost, this thesis discusses the tenuous notion of consumer agency within the current cultural context. Furthermore, I also explore these issues in relation to the wider historical post-9III context. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I offer my thanks to my supervisor, Scott Henderson, whose guidance and sense of humour were invaluable throughout work on this project. When I began work on this thesis, I found its scope intimidating and difficult to distill into a cohesive, properly structured thesis, and Scott was irreplaceable in helping me achieve this. He was an endless source of ideas, and our meetings were so light-hearted and entertaining, I never felt like we were even doing work. I also thank my parents, Bruce and Kathy, for their enthusiastic support of my education. -

Masterthesis Final.Pdf

MASTERTHESIS Herr Florian Tillack „Nach drei Staffeln ist Schluss!“ (sagen die Dänen) – Was steckt hinter erfolgreichem seriellem Erzählen? 2015 Fakultät: Medien MASTERTHESIS „Nach drei Staffeln ist Schluss!“ (sagen die Dänen) – Was steckt hinter erfolgreichem seriellem Erzählen? Autor: Herr Florian Tillack Studiengang: Information & Communication Science Seminargruppe: IC12s1-M Erstprüfer: Prof. Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Dr. Gunter Süß Faculty of Media MASTERTHESIS ‘After three seasons it’s over!” (the Danes say) – What is behind successful serial storytelling? author: Mr. Florian Tillack course of studies: Information & Communication Science seminar group: IC12s1-M first examiner: Prof. Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Dr. Gunter Süß Bibliografische Angaben Tillack, Florian: „Nach drei Staffeln ist Schluss!“ (sagen die Dänen) – Was steckt hinter erfolgreichem seriellem Erzählen? 165 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Masterthesis, 2015. Abstract Gegenstand der vorliegenden Arbeit ist die Erforschung von Gründen für die in den letzten circa 25 Jahren gestiegene Popularität zeitgenössischer Fernsehserien bei einem überwiegend jungen Publikum, der Presse und dem medienwissenschaftlichen Diskurs. Initialpunkt dieser Entwicklung ist der US-amerikanische Fernsehmarkt. Von ihm ausgehend hat das profitorientierte Wesen serieller Produktionen auf der einen und außergewöhnlicher Wagemut und Kreativität von Produzentenseite auf der anderen Seite innovative und neue Erzählformen etabliert. Der Einfluss -

Gabriel Leme Camoleze TCC 2010

GABRIEL LEME CAMOLEZE IMPACTO DA PÓS-PRODUÇÃO EM EDIÇÃO AUDIOVISUAL: ANÁLISE DAS TECNOLOGIAS EMPREGADAS NO SERIADO LOST. Assis – SP 2010 1 GABRIEL LEME CAMOLEZE IMPACTO DA PÓS-PRODUÇÃO EM EDIÇÃO AUDIOVISUAL: ANÁLISE DAS TECNOLOGIAS EMPREGADAS NO SERIADO LOST. Trabalho apresentado ao curso de Comunicação Social com Habilitação em Publicidade e Propaganda, do Instituto Municipal de Ensino Superior de Assis – IMESA/FEMA, como requisito parcial à obtenção do Certificado de Conclusão de Curso. Orientado: Gabriel Leme Camoleze Orientadora: Ma. Renata Patrícia Corrêa Coutinho Assis – SP 2010 2 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA CAMOLEZE, Gabriel Leme Impacto da Pós-Produção em Audiovisual: Análise das Tecnologias Empregadas no Seriado LOST / Gabriel Leme Camoleze. Fundação Educacional do Município de Assis – FEMA – Assis, 2010 p.94 Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso – Instituto Municipal de Ensino Superior de Assis – IMESA 1. Edição. 2. Pós-Produção. 3. Vídeo. 4. Arte CDD: 659.1 Biblioteca da FEMA 3 IMPACTO DA PÓS-PRODUÇÃO EM EDIÇÃO AUDIOVISUAL: ANÁLISE DAS TECNOLOGIAS EMPREGADAS NO SERIADO LOST. Aluno: Gabriel Leme Camoleze Orientadora: Profª Ma. Renata Patrícia Correa Coutinho Examinadora: Profª Ma. Rosemary Rocha Pereira da Silva Data da defesa: 12/11/2010 Assis – SP 2010 4 Dedicatória Dedico esta monografia primeiramente ao verdadeiro merecedor de qualquer homenagem e exaltação, de qualquer mérito ou conquista, o meu Pai e Criador, Deus. Em segundo a minha falecida mãe Silvia, que me ensinou tudo que sei, e me educou para ser quem sou hoje, sempre com muita batalha e perseverança. Tudo que eu vier a conquistar no decorrer da minha existência devo a ela. Meu Pai Elcio por sempre pensar em mim e nunca me deixar desistir, e a minha irmã Nayana, por sempre me apoiar nos estudos e na vida, em qualquer situação sabe que ela é a pessoa com quem posso contar.