2. Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polity (PRE-Cure)

Polity (PRE-Cure) April 2020 - March 2021 Visit our website www.sleepyclasses.com or our YouTube channel for entire GS Course FREE of cost Also Available: Prelims Crash Course || Prelims Test Series T.me/SleepyClasses Table of Contents Links to the videos on YouTube .................1 32. GARUD Portal ...................................18 1. Punjab Village and Small Towns Act 3 33. Samudra Setu ....................................18 2. Sections 269 & 270 IPC ................3 34. Online Summit of NAM Contact Group 3. Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana 18 3 35. “The Saras Collection” on the 4. New Domicile Rules for J&K .........5 Government e-Marketplace Portal 19 5. Medical Devices notified as Drugs 5 36. Dilution of Labour Laws .................20 6. NPPA ...................................................6 37. Data sharing under Arogya Setu Act 20 7. Lifeline UDAN ...................................6 38. Shetkar Committee recommendations 8. Stranded in India Portal .................6 accepted ...............................................21 9. PM CARES Fund ...............................6 39. GOAL Programme ............................22 10. PMNRF ...............................................7 40. Project Arth Ganga ..........................23 11. National Security Act .....................7 41. One Nation, One Channel- Education 12. MPLAD Scheme ...............................8 Initiatives .............................................23 13. Arogya Setu .......................................9 42. National Test Abhyaas App ...........24 -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Socio-Economic Issues Facing Katkaris Issues Facing Socio-Economic

2014 A Report by TataInstite of Social Sciences Socio-Economic Issues Facing Katkaris Issues Facing Socio-Economic - exclusion and deprivation of Katkaris in the districts of Raigad and Thane Region. Following mixed methods and a review of secondary literature. It details the extreme vulnerabilities faced by Katkaris in the present time. The report also suggests culturally and economically sensitive government measures for Inclusion and Development of Katkaris. Project Directors: Dr. Suryakant Waghmore Prof. Bipin Jojo Tata Institute of Social Sciences Sponsor: Rest of Maharasthra Development Board CONTENTS I Introduction ................................................................................................. 4 Geographic Location of Katkaris ...................................................................... 4 Table 1.0: Distribution of Katkari Population in Maharashtra ........................... 4 Tribals in Raigad district of Maharashtra ......................................................... 5 Research Design ............................................................................................. 6 Study Villages ................................................................................................. 6 Rapid Appraisal .............................................................................................. 6 Chapterisation ............................................................................................... 7 II Socio-Economic Status of Katkaris .............................................................. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Shughni Southern Pashto Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Wakhi Mandarin Chinese Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Domaaki Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Khowar Khowar Khowar Kati Yidgha Eastern Farsi Munji Kalasha Kati KatiKati Phalura Kalami Indus Kohistani Shina Kati Prasuni Kamviri Dameli Kalami Languages of the Gawar-Bati To rw al i Chilisso Waigali Gawar-Bati Ushojo Kohistani Shina Balti Parachi Ashkun Tregami Gowro Northwest Pashayi Southwest Pashayi Grangali Bateri Ladakhi Northeast Pashayi Southeast Pashayi Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Aimaq Parya Northern Hindko Kashmiri Northern Pashto Purik Hazaragi Ladakhi Indian Subcontinent Changthang Ormuri Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Southern Hindko Kashmiri Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Southern Pashto Ladakhi Central Pashto Khams Tibetan Kullu Pahari KinnauriBhoti Kinnauri Sunam Majhi Western Panjabi Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Chitkuli Kinnauri Mahasu Pahari Eastern Panjabi Panang Jaunsari Western Balochi Southern Pashto Garhwali Khetrani Hazaragi Humla Rawat Central Tibetan Waneci Rawat Brahui Seraiki DarmiyaByangsi ChaudangsiDarmiya Western Balochi Kumaoni Chaudangsi Mugom Dehwari Bagri Nepali Dolpo Haryanvi Jumli Urdu Buksa Lowa Raute Eastern Balochi Tichurong Seke Sholaga Kaike Raji Rana Tharu Sonha Nar Phu ChantyalThakali Seraiki Raji Western Parbate Kham Manangba Tibetan Kathoriya Tharu Tibetan Eastern Parbate Kham Nubri Marwari Ts um Gamale Kham Eastern -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Mandarin Chinese Evenki Oroqen Tuva China Buriat Russian Southern Altai Oroqen Mongolia Buriat Oroqen Russian Evenki Russian Evenki Mongolia Buriat Kalmyk-Oirat Oroqen Kazakh China Buriat Kazakh Evenki Daur Oroqen Tuva Nanai Khakas Evenki Tuva Tuva Nanai Languages of China Mongolia Buriat Tuva Manchu Tuva Daur Nanai Russian Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Russian Kalmyk-Oirat Halh Mongolian Manchu Salar Korean Ta tar Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Northern UzbekTuva Russian Ta tar Uyghur SalarNorthern Uzbek Ta tar Northern Uzbek Northern Uzbek RussianTa tar Korean Manchu Xibe Northern Uzbek Uyghur Xibe Uyghur Uyghur Peripheral Mongolian Manchu Dungan Dungan Dungan Dungan Peripheral Mongolian Dungan Kalmyk-Oirat Manchu Russian Manchu Manchu Kyrgyz Manchu Manchu Manchu Northern Uzbek Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Korean Kyrgyz Northern Uzbek West Yugur Peripheral Mongolian Ainu Sarikoli West Yugur Manchu Ainu Jinyu Chinese East Yugur Ainu Kyrgyz Ta jik i Sarikoli East Yugur Sarikoli Sarikoli Northern Uzbek Wakhi Wakhi Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Ainu Tu Wakhi Wakhi Khowar Tu Wakhi Uyghur Korean Khowar Domaaki Khowar Tu Bonan Bonan Salar Dongxiang Shina Chilisso Kohistani Shina Balti Ladakhi Japanese Northern Pashto Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Amdo Tibetan Northern Hindko Kashmiri Purik Choni Ladakhi Changthang Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Japanese Bhadrawahi Zangskari Kashmiri Baima Ladakhi Pangwali Mandarin Chinese Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Japanese Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Ladakhi Northern Qiang -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Pashto, Southern Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Shughni Chinese, Mandarin Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Wakhi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Khowar Khowar Domaaki Khowar Kati Shina Farsi, Eastern Yidgha Munji Kati Kalasha Gujari Kati KatiPhalura Gujari Kalami Shina, Kohistani Gawar-BatiKamviri Kalami Dameli TorwaliKohistani, Indus Gujari Chilisso Pashayi, Northwest Prasuni Kamviri Balti Kati Ushojo Gowro Languages of the Gawar-Bati Waigali Savi Chilisso Ladakhi Ladakhi Bateri Pashayi, SouthwestAshkun Tregami Pashayi, Northeast Shina Purik Grangali Shina Brokskat ParyaPashayi, Southeast Aimaq Shumashti Hindko, Northern Hazaragi GujariKashmiri Pashto, Northern Purik Tirahi Ladakhi Changthang Kashmiri Gujari Indian Subcontinent Gujari Pahari-PotwariGujari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Hindko, Southern Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Ormuri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Dogri-Kangri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Pashto, Southern Ladakhi Pashto, Central Khams Pahari, Kullu Kinnauri, Bhoti KinnauriSunam Gahri Shumcho Panjabi, Western Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Kinnauri, Chitkuli Pahari, Mahasu Panjabi, Eastern Panang Jaunsari Garhwali Balochi, Western Pashto, Southern Khetrani Tehri Rawat Tibetan Hazaragi Waneci Rawat Brahui Saraiki DarmiyaByangsi Chaudangsi Tibetan Balochi, Western Chaudangsi Bagri Kumauni Humla Bhotia Rangkas Dehwari Mugu Kumauni Tichurong Dolpo Haryanvi Urdu Buksa Lopa Nepali Kaike Panchgaunle Balochi, Eastern Raute Tichurong Sholaga Baragaunle Raji Nar Phu Tharu, Rana Sonha Thakali Kham, GamaleKham, Sheshi -

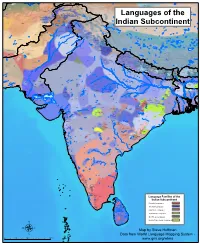

The Linguistic LANDSCAPE of INDIA India Is a Land of Around 500 Different Languages, of Which a Majority Are Used Even Today

CULTURE AND LIFESTYLE The linguistic LANDSCAPE OF INDIA India is a land of around 500 different languages, of which a majority are used even today. Sonal Kulkarni-Joshi talks about their diversity and traces their ancient global linkages ndia’s society, culture, history communication need. Among these, Visitors next to the reproduction of an and politics have continuously 121 languages have more than 10,000 ancient Sanskrit- been shaped by the multiplicity speakers and 22 of these are officially inscribed stone slab marking the India stand of her languages. So, how many recognised in the Indian Constitution. at the 2006 Frankfurt languages are spoken in India? These include Assamese, Bengali, Book Fair IThe country is home to speakers Bodo, Dogri, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, of about 461 languages. Of these, Kashmiri, Konkani, Malayalam, 447 languages are actively used in Manipuri, Marathi, Maithili, Nepali, daily communication, while 14 are Odia, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santali, extinct - they no longer fulfil any Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu and Urdu. These are referred to as the ‘scheduled spoken by most number of people languages’ and according to the its official communication tool: nation-wide census conducted in Marathi in Maharashtra, Bangla in 2011, 96.72 per cent Indians speak West Bengal, Kannada in Karnataka any one of these languages as their and so on. Hindi and the other mother tongue. Hindi is spoken by scheduled languages are also used as a majority of the Indian population official languages in the states – they (26.6 %), followed by Bangla (7.94 %), are used in regional administration Marathi (6.84 %) and Telugu (6.68 %). -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System 16 - N Ew Zealand English French Southern and Antarctic Lands

Greenland Svalbard Greenlandic Inuktitut Greenlandic Inuktitut Nganasan Nenets Dolgan Nenets Nganasan Yakut Nenets Nganasan Norwegian Nganasan Nganasan Jan Mayen Nenets Tundra Enets Dolgan North Saami North SaamiNorth Saami Nganasan Greenlandic Inuktitut North Saami Nenets Kven FinnishNorth Saami North Saami Nenets Forest Enets North Saami North Saami Skolt Saami North Saami North Saami Inari SaamiKven Finnish Forest Enets North Saami Norwegian North Saami Nenets Nenets Nenets Nenets Skolt Saami Chukchi North SaamiNorth Saami North SaamiNorth Saami Nenets Yakut North SaamiLule Saami Kildin Saami Nenets North Saami Nenets Nenets Pite Saami Tornedalen Finnish North Saami Te r Sa am i Nenets Pite SaamiPite Saami Lule Saami Nenets Nenets Tornedalen Finnish Even Lule Saami Ume Saami Pite Saami Karelian Selkup Selkup Even Icelandic Ume Saami Pite Saami Evenki Even Chukchi Iceland South Saami South SaamiUme Saami Finland Karelian Komi-Zyrian South Saami Russia Even Finnish Selkup South Saami Nenets Koryak Norway Swedish Even Sweden Swedish Even Faroese Koryak Chukchi Faroese South Saami Koryak South Saami Ludian Selkup Faroese Livvi-Karelian Veps Koryak Norwegian Evenki Alutor Koryak Koryak Veps Koryak Alutor Swedish Swedish Swedish Selkup Finnish Koryak Vod Ingrian Komi-Permyak Alutor Koryak Estonian Selkup Estonian Scottish Gaelic Estonia Evenki Scottish Gaelic Liv Itelmen Udmurt Khakas Scottish Gaelic Latvia Koryak Latvian Liv Russian Scots Denmark Meadow Mari Itelmen Scottish Gaelic Meadow Mari Danish Hill Mari Bashkort Lithuania Bashkort -

WILDRE-2 2Nd Workshop on Indian Language Data

WILDRE2 - 2nd Workshop on Indian Language Data: Resources and Evaluation Workshop Programme 27th May 2014 14.00 – 15.15 hrs: Inaugural session 14.00 – 14.10 hrs – Welcome by Workshop Chairs 14.10 – 14.30 hrs – Inaugural Address by Mrs. Swarn Lata, Head, TDIL, Dept of IT, Govt of India 14.30 – 15.15 hrs – Keynote Lecture by Prof. Dr. Dafydd Gibbon, Universität Bielefeld, Germany 15.15 – 16.00 hrs – Paper Session I Chairperson: Zygmunt Vetulani Sobha Lalitha Devi, Vijay Sundar Ram and Pattabhi RK Rao, Anaphora Resolution System for Indian Languages Sobha Lalitha Devi, Sindhuja Gopalan and Lakshmi S, Automatic Identification of Discourse Relations in Indian Languages Srishti Singh and Esha Banerjee, Annotating Bhojpuri Corpus using BIS Scheme 16.00 – 16.30 hrs – Coffee break + Poster Session Chairperson: Kalika Bali Niladri Sekhar Dash, Developing Some Interactive Tools for Web-Based Access of the Digital Bengali Prose Text Corpus Krishna Maya Manger, Divergences in Machine Translation with reference to the Hindi and Nepali language pair András Kornai and Pushpak Bhattacharyya, Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization Niladri Sekhar Dash, Generation of a Digital Dialect Corpus (DDC): Some Empirical Observations and Theoretical Postulations S Rajendran and Arulmozi Selvaraj, Augmenting Dravidian WordNet with Context Menaka Sankarlingam, Malarkodi C S and Sobha Lalitha Devi, A Deep Study on Causal Relations and its Automatic Identification in Tamil Panchanan Mohanty, Ramesh C. Malik & Bhimasena Bhol, Issues in the Creation of Synsets in Odia: A Report1 Uwe Quasthoff, Ritwik Mitra, Sunny Mitra, Thomas Eckart, Dirk Goldhahn, Pawan Goyal, Animesh Mukherjee, Large Web Corpora of High Quality for Indian Languages i Massimo Moneglia, Susan W. -

View by Puja Roy

Cover image: S j Fotografy CLASS OF 2013-14 HWÆTHWUGU Cædmon, the shy cowherd, left the banquet when he couldn’t take his turn singing like everyone else. In his dream, an angel came to him, coaxing him to sing, “Sing me hwæthwugu!” said the angel, meaning, in Old English, “Sing me Something!” and coaxed him further. It was the angel’s encouragement that resulted in the creation of the first poem in English, Cædmon’s Hymn of Creation. Hwæthwugu, or ‘something’, then, is that indescribable element which can make literature come alive, it is that which can make shy cowherds sing and fill their song with a touch of some mysterious reality, not of this world. Hwæthwugu is that secret element added by every writer, every creator to their work, as they pour a part of themselves into what they write. One sees the writers come alive through their Manuscript of Bede’s History of the English Church writing, because writing is more than and People, showing Cædmon’s Hymn, written out in simply words, it is something beyond prose as he sang the angel something, and so sang the words ... hymn of frumsceaft — Creation) Hwæthwugu... it is in the smell of old parchment, in the yellowing of the pages, it is the secret of the scent of books forgotten for many ages... 1 EDITORS Editor Dr. Prachi Khandeparkar Creative Editors Pankti Shah Shraddha Indulkar Assistant Editors Ms. Divya Bhatnagar Varun Gwalani Disha Sanghvi 2 CONTENTS Message from the Principal ...................................................................................... 4 Message from the Head of the Department ............................................................. 5 Editorial .................................................................................................................. -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.7631(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 7 | issUe - 11 | aUGUst - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ HEALTH STATUS OF KATHODI KATKARI TRIBE IN KARNATAKA Bhaskar Basapur1 and Dr. Ravi S. Dalawai2 1 Research Scholar , Dept of Sociology , Rani Channamma University,Belagavi . 2 Research Guide , Assistant Professor Dept of Sociology , Rani Channamma University, Belagavi. ABSTRACT Kathodi Katkari tribe community resides in Forest virgin of Khanapur Taluk of Belagavi district. This community has originated in Maharashtra State. The primary occupation of Kathodi Katkari tribe is to cut trees. This people of this tribe talk their own Tribal language and this called as Katkari. This tribe is not aware of cleanliness and sanitation. The people of this tribe do not bath daily. The people of Kathodi Katkari tribe Deliver babies at the home. Child marriage is observed in the Tender age when girl of this grow 14 to 16 years and when boy 16 to 18 years they get married. The people use traditional medicines. KEY WORD: Kathodi Katkari, Health, Child Marraige, Traditional Medicine, Migration, Jasmine Bark, Vaivadanga. INTRODUCTION Some of the tribal communities do not have the permanent settlement, these tribal communities always keep migrating from one place to other. Kathodi Katkari tribal community is one amongst such tribal communities. Kathodi Katkari tribal community resides in forest region of Khanapur taluk of Belagavi district. This community has originated in Maharashtra state. They have migrated from Maharashtra to Karnataka several years ago. The primary occupation of Kathodi Katkari tribe is to cut trees. This tribe used to extract liquor named Kath through distillation process from the bark of trees. -

Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization

Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization Andras´ Kornai, Pushpak Bhattacharyya Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Department of Algebra Indian Institute of Technology, Budapest Institute of Technology [email protected], [email protected] Abstract We describe the planned Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization (ISLV) project, which aims at turning as many languages and dialects of the subcontinent into digitally viable languages as feasible. Keywords: digital vitality, language vitalization, Indian subcontinent In this position paper we describe the planned Indian Sub- gesting that efforts aimed at building language technology continent Language Vitalization (ISLV) project. In Sec- (see Section 4) are best concentrated on the less vital (but tion 1 we provide the rationale why such a project is called still vital or at the very least borderline) cases at the ex- for and some background on the language situation on the pense of the obviously moribund ones. To find this border- subcontinent. Sections 2-5 describe the main phases of the line we need to distinguish the heritage class of languages, planned project: Survey, Triage, Build, and Apply, offering typically understood only by priests and scholars, from the some preliminary estimates of the difficulties at each phase. still class, which is understood by native speakers from all walks of life. For heritage language like Sanskrit consider- 1. Background able digital resources already exist, both in terms of online The linguistic diversity of the Indian Subcontinent is available material (in translations as well as in the origi- remarkable, and in what follows we include here not nal) and in terms of lexicographical and grammatical re- just the Indo-Aryan family, but all other families like sources of which we single out the Koln¨ Sanskrit Lexicon Dravidian and individual languages spoken in the broad at http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/monier and the geographic area, ranging from Kannada and Telugu INRIA Sanskrit Heritage site at http://sanskrit.inria.fr.