THE LAWRENCES of the PUNJAB All Rights Reserved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Garden of India; Or, Chapters on Oudh History and Affairs

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES ^ AMSTIROAM THE GARDEN OF INDIA. THE GARDEN or INDIA; OR CHAPTERS ON ODDH HISTORY AND AFFAIRS. BY H. C. IHWIN, B.A. OxoN., B.C.S. LOHf D N: VV. H. ALLEN <t CO., 13 WATERLOO TLACE. PUBLISH KUS TO THK INDIA OKKICK. 1880. Mil rtg/ito reMrvedij LONDON : PRINTP.D BT W. H. ALLKN AND CO , 13 iVATERLOO PLACK, S.W. D5 7a TO MI BROTHER OFFICERS OF THE OUDH COMMISSION I BEG LEAVE TO INSCRIBE THIS LITTLE BOOK WITH A PROFOUND SENSE OF ITS MANY DEFICIENCIES BUT IN THE HOPE THAT HOWEVER WIDELY SOME OP THEM MAY DISSENT FROM NOT A FEW OF THE OPINIONS I HAVE VENTURED TO EXPRESS THEY WILL AT LEAST BELIEVE THAT THESE ARE INSPIRED BY A SINCERE LOVE OF THE PROVINCE AND THE PEOPLE WHOSE WELFARE WE HAVE ALL ALIKE AT HEART. a 3 : ' GHrden of India I t'adinjj flower ! Withers thy bosom fair ; State, upstart, usurer devour What frost, flood, famine spare." A. H. H. "Ce que [nous voulonsj c'est que le pauvre, releve de sa longue decheance, cesse de trainer avec douleur ses chaines hereditaires, d'etre an pur instrument de travail, uue simple matiere exploitable Tout effort qui ne produirait pas ce resultat serait sterile ; toute reforme dans les choses presentes qui n'aboutirait point a cette reforme fonda- meutale serait derisoire et vaine." Lamennais. " " Malheur aux resignes d'aujourd'hui ! George Sand. " The dumb dread people that sat All night without screen for the night. All day mthout food for the day, They shall give not their harvest away, They shall eat of its frtiit and wax fat They shall see the desire of their sight, Though the ways of the seasons be steep, They shall climb mth face to the light, Put in the sickles and reap." A. -

The Lucknow Album

' <f5S; : THE LUCKNOW ALBUM. CONTAINING A SERIES OF FIFTY PHOTOGRAPHIC VIEWS OF LUCKNOW AND ITS ENVIRONS TOGETHEK WITH A LAEGE SIZED PLAN OF THE CITY EXECUTED BY Darogha Ubbas Alli Assistant Municipal Engineer. o:**;o TO THE ABOVE IS ADDED A FULL DESCRIPTION OF EACH SCENE DEPICTED. THE WHOLE FOEMING A COMPLETE ttJCTTSXRATED &XHCDE TO THE CITY OF LTJCKNOW THE CAPITAL OF OUDH. =-§«= CALCUTTA Printed by p. ji, J<ouse, ]3aptist yVlissiON T^ress. 1874. \thmkh frg fmroioti TO SiFy_ George Coupei\, JBart., C. j3 CHIEF COMMISSIONER OF OUDH. s . CONTENTS. Ho*- Page 1-2.—Aulum Bagh, and General Havelock's tomb, 6-7 3. Bebeapore ki — Kothe, , . 9 4.—The Welaite Bagh, ,., 10 5. —Dilkoosba, ih. 6. —La Martiniere, \\ 7. —Hyat Buksb, 13 8. Darul Shaffa , — , $. 9.—Tbe Offices of the Oudh and Eohilcund Railway Company, 15 1 0.—St. Joseph's Church, ib. 11 . — Christ's Church, $. 12.—Wingfield Park, , 16 13.— Sekunder Bagh, 17 14. —Kuddum Russool, 18 15. —Najuf Ashruf or Shah Najaf, $, 16.—Mote Mahal, 19 3 7.— Khoorshaid Munzil, 20 18. —Tara Kothe or Star House, 21 19. —Memorial of the Massacre of European Captives, ......... 22 20. —ivunkur Wali Kothi, 23 21. —Noor Bukhsh ki Kothi or Light-giving House, H, 22, 23, 24.—Kaiser Bagh or Caesar's Garden, 25 25, 26.—Saadut Ali Khan's Tomb, and Moorshed Zadi's Tomb, 27 27.—Kaiser Pussund, 29 28—Neil's Gate, #. 29. —Bruce's Bridge, 31 30, 31.—Chutter Munzil, , ,-j. 32. —Lai Baradurree, ....*, t 32 Guard, 33, 34.—Bailie , 33 35.—Bulrampore Hospital, 46 ( vi ) Nos. -

THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY of INDIA Indian Society and The

THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA Indian society and the making of the British Empire Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA General editor GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Associate editors CA. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine's College and JOHN F. RICHARDS Professor of History, Duke University Although the original Cambridge History of India, published between 1922. and 1937, did much to formulate a chronology for Indian history and de- scribe the administrative structures of government in India, it has inevitably been overtaken by the mass of new research published over the last fifty years. Designed to take full account of recent scholarship and changing concep- tions of South Asia's historical development, The New Cambridge History of India will be published as a series of short, self-contained volumes, each dealing with a separate theme and written by a single person. Within an overall four-part structure, thirty-one complementary volumes in uniform format will be published. As before, each will conclude with a substantial bib- liographical essay designed to lead non-specialists further into the literature. The four parts planned are as follows: I The Mughals and their contemporaries II Indian states and the transition to colonialism III The Indian Empire and the beginnings of modern society IV The evolution of contemporary South Asia A list of individual titles in preparation will be found at the end of the volume. -

1 the Discourse of Colonial Enterprise and Its Representation of the Other Through the Expanded Cultural Critique

Notes 1 The discourse of colonial enterprise and its representation of the other through the expanded cultural critique 1. I use the term “enterprise” in a delimited manner to specifically denote the colonial enterprise of capitalism and corporate enterprise of multi-nationals under global capitalism. I also examine the subversion of the colonialist capitalist enterprise through the deployment of indigenous enterprise in Chapter 4. It is not within the purview of my project to examine the history of the usage of the term “enterprise” in its medieval and military context. 2. Syed Hussein Alatas in a 1977 study documents and analyses the origins and function of what he calls the myth of the lazy native from the sixteenth to the twentieth century in Malaysia, Philippines, and Indonesia. See his The Myth of the Lazy Native (1977). I pay tribute to this excellent study; however, my own work differs from Alatas in the following respects. Alatas treats colonialist labour practices as an ideology or a patently false “myth” not as discourse. Unlike Alatas my own study of labour practices is oriented towards discourse analysis. This difference in tools leads to a more fundamental theoretical divergence: Alatas foregrounds the myth of the lazy native without investigating the binary half of the industrious European that sustains the former. Contrarily I argue that the colonized native’s unproductive work and play within the expanded cultural critique cannot be discussed without taking into account the normative labour and leisure practices in post-Enlightenment enterprise. 3. My choice of the Defoe text, as well as my locating the colonial capitalist discourses of labour in the English Enlightenment is influenced by Marx’s brief but intriguing interpretation of Defoe’s Crusoe. -

1 TRIBE and STATE in WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis

1 TRIBE AND STATE IN WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis presented for PhD degree at the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673067 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673067 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT The thesis begins by describing the socio-political and economic organisation of the tribes of Waziristan in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as aspects of their culture, attention being drawn to their egalitarian ethos and the importance of tarburwali, rivalry between patrilateral parallel cousins. It goes on to examine relations between the tribes and the British authorities in the first thirty years after the annexation of the Punjab. Along the south Waziristan border, Mahsud raiding was increasingly regarded as a problem, and the ways in which the British tried to deal with this are explored; in the 1870s indirect subsidies, and the imposition of ‘tribal responsibility’ are seen to have improved the position, but divisions within the tribe and the tensions created by the Second Anglo- Afghan War led to a tribal army burning Tank in 1879. -

Biography of Thomas Valpy French

THOMAS VALPY FRENCH, FIRST BISHOP OF LAHORE By Vivienne Stacey CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introductory – Burton- on-Trent, Lahore, Muscat 2 Chapter 2 Childhood, youth and. early manhood 10 Chapter 3 The voyage, first impressions, St. John’s College Agra 16 Chapter 4 Agra in the 1850’s 25 Chapter 5 French’s first furlough and his first call to the Dejarat 36 Chapter 6 Six years in England, 1863-1869 46 Chapter 7 St. John’s Divinity School, Lahore 55 Chapter 8 The creation of’ the Diocese at Lahore 69 Chapter 9 The building of the Cathedral of the Resurrection, Lahore 75 Chapter 10 The first Bishop of Lahore 1877 – 1887 84 Chapter 11 Resignation. Journey to England through the Middle East 97 Chapter 12 Call to Arabia and death in Muscat 108 Some important dates 121 Bib1iography primary sources 122 secondary sources 125 1 Chapter 1: Introductory. Burton-on Trent, Lahore, Muscat Three thousand or so Pakistanis are camped in the half-built town of Salalah in the Sultanate of Oman. They are helping to construct the second largest city of Oman – most of them live in tents or huts. Their size as a community is matched by the Indian commu- nity also helping in this work and in the hospital and health pro- grammes. Among the three thousand Pakistanis perhaps three hundred belong to the Christian community. Forty or so meet for a service of worship every Friday evening – they are organized as a local congregation singing psalms in Punjabi and hearing the Holy Bible expounded in Urdu. -

Nineteenth-Century Army Officers'wives in British

IMPERIAL STANDARD-BEARERS: NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARMY OFFICERS’WIVES IN BRITISH INDIA AND THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation by VERITY GAY MCINNIS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2012 Major Subject: History IMPERIAL STANDARD-BEARERS: NINETEENTH-CENTURY ARMY OFFICERS’WIVES IN BRITISH INDIA AND THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation by VERITY GAY MCINNIS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, R.J.Q. Adams J. G. Dawson III Committee Members, Sylvia Hoffert Claudia Nelson David Vaught Head of Department, David Vaught May 2012 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT Imperial Standard-Bearers: Nineteenth-Century Army Officers’ Wives in British India and the American West. (May 2012) Verity Gay McInnis, B.A., Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi; M.A., Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee: Dr. R.J.Q. Adams Dr. Joseph G. Dawson III The comparative experiences of the nineteenth-century British and American Army officer’s wives add a central dimension to studies of empire. Sharing their husbands’ sense of duty and mission, these women transferred, adopted, and adapted national values and customs, to fashion a new imperial sociability, influencing the course of empire by cutting across and restructuring gender, class, and racial borders. Stationed at isolated stations in British India and the American West, many officers’ wives experienced homesickness and disorientation. -

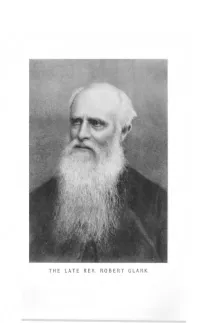

The Late Rev. Robert Clark. the Missions

THE LATE REV. ROBERT CLARK. THE MISSIONS OF THE CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY A~D THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND ZENANA MISSIONARY · SOCIETY IN THE PUNJAB AND SINDH BY THE LATE REv. ROBERT CLARK, M.A. EDITED .AND REPISED BY ROBERT MACONACHIE, LATE I.C.S. LONDON: CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY SALi SBU R Y SQUARE, E.C. 1904 PREFATORY NOTE. --+---- THE first edition of this book was published in 18~5. In 1899 Mr. Robert Clark sent the copy for a second and revised edition, omitting some parts of the original work, adding new matter, and bringing the history of the different branches of the Mission up to date. At the same time he generously remitted a sum of money to cover in part the expense of the new edition. It was his wish that Mr. R. Maconachie, for many years a Civil officer in the Punjab, and a member of the C.M.S. Lahore Corre sponding Committee, would edit the book; and this task Mr. Maconachie, who had returned to England and was now a member of the Committee at home, kindly undertook. Before, however, he could go through the revised copy, Mr. Clark died, and this threw the whole responsibility of the work upon the editor. Mr. Maconachie then, after a careful examination of the revision, con sidered that the amount of matter provided was more than could be produced for a price at which the book could be sold. He therefore set to work to condense the whole, and this involved the virtual re-writing of some of the chapters. -

Masterly Inactivity’: Lord Lawrence, Britain and Afghanistan, 1864-1879

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ ‘Masterly inactivity’: Lord Lawrence, Britain and Afghanistan, 1864-1879 Wallace, Christopher Julian Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 1 ‘Masterly inactivity’: Lord Lawrence, Britain and Afghanistan, 1864-1879 Christopher Wallace PhD History June 2014 2 Abstract This dissertation examines British policy in Afghanistan between 1864 and 1879, with particular emphasis on Sir John Lawrence’s term as governor-general and viceroy of India (1864-69). -

One Hundred Years

ONE HUNDRED YEARS BEING THE SHORT HISTORY OF THE CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY "1tbou ebalt remember all tbe wa'!? wblcb tbe 1orb tb'!? Gob kb tbec." ,DET. Tiii. ! ~birlJ <$bition LONDON CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY SALISBURY SQUARE, E.C. 1899 PREFACE. HIS little book has been written for publication in advance of the complete· History of the Church Missionary Society. The greater part of it con sists of a very brief summary of some of the facts D given in the larger work ; and here and there sentences and paragraphs are actually reproduced from the still unpublished volumes. But part of Chapter IX., and Chapters X. and XI., have had to be written before the corresponding portions of the complete History. · To many of the most · important parts of the complete History, however, there is nothing corresponding in these pages. For the History dwells at some length upon the environment of the Society at different periods in the century, that is to say, upon the state of the Church of England at home, noticing various religious movements, developments, and controversies, and introducing such men as Bishops Blomfield and Wilberforce, Archbishops Tait and Benson, Lords Shaftesbury and Cairns, Sir Arthur Blackwood and Mr. Pennefather, Bishop Ryle and Canon Hoare. Also upon the progress of Christian Missions generally, with references to the work of men like Bishops Selwyn, Patteson, and Steere, of Morrison, Livingstone, and Hudson Taylor. Also upon public events and affairs abroad which have affected Missions, such as the Slave Trade, African Exploration, the Opium Traffic, the colonization of New Zealand, and a whole series of important events in India. -

The Life of Hodson of Hodson's Horse

EVERYMAN. I-W1LLGO-W1TH THEE. &BETHYGV1DE JN THY MOST- NEED' ITOGOBY-THY-5JDE THE PUBLISHERS OF LlB cR^tcRy WILL BE PLEASED TO SEND FREELY TO ALL APPLICANTS A LIST OF THE PUBLISHED AND PROJECTED VOLUMES TO BE COMPRISED UNDER THE FOLLOWING TWELVE HEADINGS: TRAVEL ^ SCIENCE ^ FICTION THEOLOGY & PHILOSOPHY HISTORY ^ CLASSICAL FOR YOUNG PEOPLE ESSAYS ^ ORATORY POETRY & DRAMA BIOGRAPHY ROMANCE IN TWO STYLES OF BINDING, CLOTH, FLAT BACK, COLOURED TOP, AND LEATHER, ROUND CORNERS, GILT TOP. LONDON : J. M. DENT & SONS, LTD. NEW YORK: E. P. BUTTON & CO. Life gf -\ HODSON^ HODSON'S HORSE : BY Captain Lionel J TROTTER LONDON: PUBLISHED byJ-M-DENT ^-SONS-HP AND IN NEW YORK*! BY E-P- DUTTON^CO INTRODUCTION 1 AMONG the men who fought and bled in their country's service during the flood-tide of the Indian Mutiny, few names shone with a steadier and more inspiring lustre than that of William S. R. Hodson, the prince of scout- ing officers, the bold and skilful leader of Hodson's Horse. From the middle of May to the close of Sep- tember, 1857, the fame of his achievements rang daily louder in the field force which Barnard led from Karnal to the siege of Delhi. During the next six months he contrived to add some new and noteworthy services to a record already blazing with heroic deeds. Dying as a brevet-major in the prime of his strenuous manhood, he had already won for himself a proud place on the honour-lists of our long island story. Hodson's claim to be remembered as a great soldier has never been questioned even by the boldest assailants of his moral rectitude or of his fitness for civil rule. -

Child Characters in Victorian and Postcolonial Fiction, 1814 - 2006

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Works in Progress: Child Characters in Victorian and Postcolonial Fiction, 1814 - 2006 Kiran Mascarenhas Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/364 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Works in Progress: Child Characters in Victorian and Postcolonial Fiction, 1814 – 2006 By Kiran Mascarenhas A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the City University of New York 2014 ii © Kiran Mascarenhas All Rights Reserved iii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. __________ _____________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee, Ashley Dawson, Ph.D. __________ _____________________________________________ Date Executive Officer, Mario DiGangi, Ph.D. Talia Schaffer, Ph.D. Timothy Alborn, Ph.D. Supervisory Committee iv The City University of New York Abstract Works in Progress: Child Characters in Victorian and Postcolonial Fiction, 1814 – 2006 By Kiran Mascarenhas Advisers: Ashley Dawson, Talia Schaffer In this dissertation I analyze the relationship between national and individual development in Victorian and postcolonial novels set in India. My central argument is that the investment in the idea of progress that characterizes colonial narratives of childhood gives way in postcolonial fiction to a suspicion of dominant understandings of progress, and that this difference is manifest in the identity formation of the child character as well as in the form of the novel.