University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Mmmmmmm I I Mmmmmmmmm I M I M I

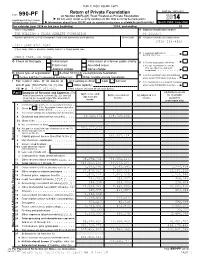

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ¸ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2014 or tax year beginning , 2014, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE WILLIAM & FLORA HEWLETT FOUNDATION 94-1655673 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (650) 234 -4500 2121 SAND HILL ROAD City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code m m m m m m m C If exemption application is I pending, check here MENLO PARK, CA 94025 G m m I Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm here m mand m attach m m m m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminatedm I Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I J X Fair market value of all assets at Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminationm I end of year (from Part II, col. -

![Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8021/howl-the-naked-bodies-of-madness-118021.webp)

Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10352/ Published chapter Rodosthenous, George (2005) The dramatic imagery of "Howl": the [naked] bodies of madness. In: Howl for Now. Route Publishing , Pontefract, UK, pp. 53- 72. ISBN 1 901927 25 3 White Rose Research Online [email protected] The dramatic imagery of “Howl”: the [naked] bodies of madness George Rodosthenous …the suffering of America‘s naked mind for love into an eli eli lamma lamma sabacthani saxophone cry that shivered the cities (―Howl‖, 1956) Unlike Arthur Rimbaud who wrote his ―A Season in Hell‖ (1873) when he was only 19 years old, Allen Ginsberg was 29 when he completed his epic poem ―Howl‖ (1956). Both works encapsulate an intense world created by the imagery of words and have inspired and outraged their readers alike. What makes ―Howl‖ relevant to today, 50 years after its first reading, is its honest and personal perspective on life, and its nearly journalistic, but still poetic, approach to depicting a world of madness, deprivation, insanity and jazz. And in that respect, it would be sensible to point out the similarities of Rimbaud‘s concerns with those of Ginsberg‘s. They both managed to create art that changed the status quo of their times and confessed their nightmares in a way that inspired future generations. Yet there is a stark contrast here: for Rimbaud, ―A Season in Hell‖ was his swan song; fortunately, in the case of Ginsberg, he continued to write for decades longer, until his demise in 1997. -

R0693-05.Pdf

I' i\ FILE NO .._O;:..=5:....:::1..;::..62;;;;..4:..- _ RESOLUTION NO. ----------------~ 1 [Howl Week.] 2 3 Resolution declaring the week of October 2-9 Howl Week in the City and County of San 4 Francisco to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the first reading of Allen Ginsberg's 5 classic American poem about the Beat Generation. 6 7 WHEREAS, Allen Ginsberg wrote Howl in San Francisco, 50 years ago in 1955; and 8 ! WHEREAS, Mr. Ginsberg read Howl for the first time at the Six Gallery on Fillmore 9 I Street in San Francisco on October 7, 1955; and 10 WHEREAS, The Six Gallery reading marked the birth of the Beat Generation and the 11 I start not only of Mr. Ginsberg's career, but also of the poetry careers of Michael McClure, 12 Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Philip Whalen; and 13 14 WHEREAS, Howl was published by Lawrence Ferlinghetti at City Lights and has sold 15 nearly one million copies in the Pocket Poets Series; and 16 WHEREAS, Howl rejuvenated American poetry and marked the start of an American 17 Cultural Revolution; and 18 WHEREAS, The City and County of San Francisco is proud to call Allen Ginsberg one 19 of its most beloved poets and Howl one of its signature poems; and, 20 WHEREAS, October 7,2005 will mark the 50th anniversary of the first reading of 21 HOWL; and 22 WHEREAS, Supervisor Michela Alioto-Pier will dedicate a plaque on October 7,2005 23 at the site of Six Gallery; now, therefore, be it 24 25 SUPERVISOR PESKIN BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Page 1 9/20/2005 \\bdusupu01.svr\data\graups\pElskin\iagislatiarlire.soll.ltrons\2005\!lo\l'lf week 9.20,05.6(J-(; 1 RESOLVED, That the San Francisco Board of Supervisors declares the week of 2 October 2-9 Howl Week to commemorate the 50th anniversary of this classic of 20th century 3 American literature. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Statement for the Library of Congress Study on the Current State Of

Library of Congress Study on the Current State of Recorded Sound Preservation and Restoration Statement by Margaret A. Compton, Film, Videotape, & Audiotape Archivist Ruta Abolins, Director The Walter J. Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection University of Georgia Libraries, Athens, Georgia The University of Georgia Library preserves a substantial amount of archival audio material of all formats in both the Peabody Awards Archives and the Walter J. Brown Media Archives. The Peabody Award is one of the most respected and coveted awards in broadcasting. It was conceived in 1939 by Lambdin Kay, manager of WSB Radio in Atlanta, and sponsored by John E. Drewry, dean of the Grady School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Georgia. The first awards were given in 1940 for radio broadcasts of 1939. Television entries began in 1949. Just this year, over 1,100 audio and visual entries were received at the awards office, totaling approximately 5,000 physical documents which will be added to the archives after judging is complete. The Peabody Awards Archives is administrated by the University of Georgia library and is housed in the Main Library on campus. This archives is important for studying the history of broadcasting, since every entry submitted—not just those which win Peabody Awards—has been kept, along with any paper material and ephemera submitted with the programs, preserving a snapshot of the best in annual broadcasting from around the world. The Library’s Walter J. Brown Media Archives is made up of a broader range of campus, local, and southeast regional archival audio and visual materials. -

The Impact of Pacifica Foundation on Two Traditions of Freedom of Expression

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 27 Issue 4 Article 3 1978 The Impact of Pacifica oundationF on Two Traditions of Freedom of Expression Stephen W. Gard Cleveland- Marshall College of Law Jeffrey Endress Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the First Amendment Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Stephen W. Gard and Jeffrey Endress, The Impact of Pacifica oundationF on Two Traditions of Freedom of Expression, 27 Clev. St. L. Rev. 465 (1978) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol27/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES THE IMPACT OF Pacifica FoundationON TWO TRADITIONS OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION STEPHEN W. GARD* AND JEFFREY ENDREssf I. INTRODUCTION T HERE EXIST IN THIS NATION TWO TRADITIONS of freedom of expression: "that of the written and spoken word and that of the broadcast word."' The contrast between these two traditions is extraordinary. The first has its 2 roots in the historic rejection of administrative licensing of the written word and the popular repudiation of the Alien and Sedition Act of 1798.3 This tradition regards prior restraints as virtually verboten4 and all governmental regulation of the content of expression as inherently suspect.5 In short, here freedom of speech is the rule and governmental regulation is an exception to be jealously confined within narrow, judicially defined, limits. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

The Digital Dilemma 2 Perspectives from Independent Filmmakers, Documentarians and Nonprofi T Audiovisual Archives

Copyright ©2012 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. “Oscar,” “Academy Award,” and the Oscar statuette are registered trademarks, and the Oscar statuette the copyrighted property, of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The accuracy, completeness, and adequacy of the content herein are not guaranteed, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences expressly disclaims all warranties, including warranties of merchantability, fi tness for a particular purpose and non-infringement. Any legal information contained herein is not legal advice, and is not a substitute for advice of an attorney. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this document may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Inquiries should be addressed to: Science and Technology Council Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences 1313 Vine Street, Hollywood, CA 90028 (310) 247-3000 http://www.oscars.org Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Digital Dilemma 2 Perspectives from Independent Filmmakers, Documentarians and Nonprofi t Audiovisual Archives 1. Digital preservation – Case Studies. 2. Film Archives – Technological Innovations 3. Independent Filmmakers 4. Documentary Films 5. Audiovisual I. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and -

Station List

IN THIS ISSUE -NEW! FM Station I o List C ILA HUGO GERHSBACK, Editor BRUNETTI WRIST-WATCH TRANSMITTER SEE PAGE 28 SALES of previous editions offer the best evidence of its worth. Edition Year Copies sold 1st 1937 51,000 2nd 1938 25,000 3rd 1939 55,000 4th 1941 60,000 5th 1946 75,000 Here's what you get: Data on correct replace- ment parts Circuit information Servicing hints Installation notes IF peaks Tube complements and number of tubes References to Rider, giving Ready April 1st volume and page number RESERVE YOUR The 6th Edition COPY NOW Mallory Radio Service Encyclopedia Here it is -up to date -the only accurate, authorita- number of tubes ... and in addition, cross -index to tive radio service engineers guide, complete in one Rider by volume and page number for easy reference. GIVES YOU ALL THIS IN- volume -the Mallory Radio Service Encyclopedia, NO OTHER BOOK FORMATION- that's why it's a MUST for every 6th Edition. radio service engineer. Made up in the same easy -to -use form that proved 25% more listings than the 5th Edition. Our ability so popular in the 5th Edition, it gives you the to supply these books is taxed to the limit. The only complete facts on servicing all pre -war and post -war way of being sure that you will get your copy quickly sets ... volume and tone controls, capacitors, and is to order a copy today. Your Mallory Distributor vibrators ... circuit information, servicing hints, will reserve one for you. The cost to you is $2.00 net. -

Radio and Television Station Transfers: Adequacy of Supervision Under the Federal Communications Act

Indiana Law Journal Volume 30 Issue 3 Article 6 Spring 1955 Radio and Television Station Transfers: Adequacy of Supervision under the Federal Communications Act Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Communications Law Commons Recommended Citation (1955) "Radio and Television Station Transfers: Adequacy of Supervision under the Federal Communications Act," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 30 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol30/iss3/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES RADIO AND TELEVISION STATION TRANSFERS:. ADEQUACY OF-SUPERVISION UNDER THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS ACT Over five hundred radio and television stations were transferred in a recent twelve month period reflecting the increasing significance of transfers in regulation of the industry.1 While the history of radio regu- lation traces back to 1910,2 the first legislation controlling transfers was the Radio Act of 1927 which required "the consent in writing of the licensing authority."3 The Communications Act of 1934 re-enacted this provision and added the "public interest" criterion as a basis for judging transfers.4 Under this vague statutory mandate,, the FCC has empha- sized a number of factors in approving or disapproving transfer applica- 1. For purposes of this Note, "transfer" will refer to transfer and assignment of stations (which naturally includes the license), and transfers of construction permits. -

“A Certain Stigma” of Educational Radio: Judith Waller and “Public Service” Broadcasting Amanda R

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Communication, College of Publications 1-1-2017 “A Certain Stigma” of Educational Radio: Judith Waller and “Public Service” Broadcasting Amanda R. Keeler Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. Critical Studies in Media Communication, Vol. 34, No. 5 (2017): 495-508. DOI. © 2017 Taylor & Francis Group. Used with permission. Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Publications/Department of Communication This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; but the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation below. Critical Studies in Media Communication, Vol. 34, No. 5 (2017): 495-508. DOI. This article is © Taylor & Francis (Routledge) and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e- Publications@Marquette. Taylor & Francis (Routledge) does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Taylor & Francis (Routledge). “A certain stigma” of educational radio: Judith Waller and “public service” broadcasting Amanda Keeler Department of Digital Media and Performing Arts, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI Abstract This paper explores Judith Waller’s radio programming philosophy over her career that began in 1922 at WMAQ Chicago. In the 1940s, representing the interests of her employer NBC, Waller began to use the phrase “public service” as a way to break free of the “stigma” of educational radio. The concept of public service programming shifted during the 1930s and 1940s in the US, redefined and negotiated in response to assumptions about radio listeners, the financial motivations of commercial radio, and Federal Communications Commission rulings. -

Jones-11-OCR-Page-0025.Pdf

Bakersfield Livermore Pacific Grove San Francisco (Cont) KGFM 101.5 I KKIQ 101.7 I KOCN 104.9 KSFX 103.7 F I KIFM 96.5 Lodi Palm Springs * KUSF 90.3 I KLYD-FM 94. 1 E I KWIN 97.7 I KOES-FM 104.7 I KYA-FM 93.3 I KUZZ-FM 107.9 Loma Linda Pasadena San Jose Berkeley * KEMR 88.3 '* KPCS 89.3 R I KBAY 100.3 * KALX 90.7 Lompoc I KROQ-FM 106.7 KEZR 106.5 '* KPFA 94. 1 R KLOM-FM 92.7 Paso Robles I KOME 98.5 * KPFB 89.3 Long Beach I KPRA 94.3 I KSJO 92.3 F I KRE-FM 102.9 E Patterson * KLON 88.l R * KSJS 90.7 Big Bear Lake I KNAC I KOSO 93.1 G 105.5 San Luis Obispo I KTOT-FM 101.7 I KNOB 97.9 Pismo Beach * KCBX 90.l Bishop * KSUL KPGA 95.3 90.1 * KCPR 91.3 E t KIOQ-FM 100.7 Porterville Los Altos I KUNA 96. l Blythe KIOO 99.7 * KFJC 89.7 I KZOZ 93.3 KYOR-FM 100.3 Quincy I KPEN 97.7 San Mateo Buena Park KFRW 95.9 Los Angeles * KCSM 91.1 R * KBPK 90.1 Redding I KBCA 105.1 I KSOL 107.7 Camarillo KVIP-FM 98.1 KBIG 104.3 San Rafael I KEWE 95.9 F - Redlands I KFAC FM 92.3 I KTIM-FM 100.9 M Cerlsbad KCAL-FM 96.7 I KFSG 96.3 Santa Ana I KARL-FM 95.9 * KUOR-FM 89.1 I KGBS-FM 97.1 D I KWIZ-FM 96.7 Carmel Redondo Beach KHOF 99.5 I KYMS 106.3 D I KLRB 101.7 I KKOP 93.5 I KIQQ 100.3 E Santa Barbara cathedral City Rio Vista I KJOI 98.7 '* KCSB-FM 91.5 I KWXY-FM 103.l * KRVH 90.9 I KKDJ 102.7 G I KDB-FM 93.7 Chico Riverside I KLOS 95.5 I KRUZ 103.3 E * KCHO 91.1 KBBL 99.