Experimental Sound & Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Mmmmmmm I I Mmmmmmmmm I M I M I

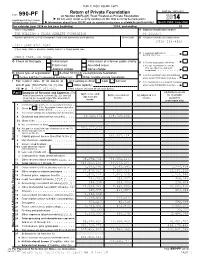

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ¸ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2014 or tax year beginning , 2014, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE WILLIAM & FLORA HEWLETT FOUNDATION 94-1655673 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (650) 234 -4500 2121 SAND HILL ROAD City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code m m m m m m m C If exemption application is I pending, check here MENLO PARK, CA 94025 G m m I Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm here m mand m attach m m m m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminatedm I Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I J X Fair market value of all assets at Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminationm I end of year (from Part II, col. -

Bilaga C Exempel På Abuseärenden

Bilaga C Exempel på abuseärenden Notera att information om avsändare och annan personlig information är borttagen ur dessa exempel. Exempel 1 – Copyright Compliance Notice ID: 22-102071976 Notice Date: 28 Aug 2013 03:56:47 GMT Foreningen For Digitala Fri- Och Rattigheter Dear Sir or Madam: Irdeto USA, Inc. (hereinafter referred to as "Irdeto") swears under penalty of perjury that Paramount Pictures Corporation ("Paramount") has authorized Irdeto to act as its non-exclusive agent for copyright infringement notification. Irdeto's search of the protocol listed below has detected infringements of Paramount's copyright interests on your IP addresses as detailed in the below report. Irdeto has reasonable good faith belief that use of the material in the manner complained of in the below report is not authorized by Paramount, its agents, or the law. The information provided herein is accurate to the best of our knowledge. Therefore, this letter is an official notification to effect removal of the detected infringement listed in the below report. The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, the Universal Copyright Convention, as well as bilateral treaties with other countries allow for protection of client's copyrighted work even beyond U.S. borders. The below documentation specifies the exact location of the infringement. We hereby request that you immediately remove or block access to the infringing material, as specified in the copyright laws, and insure the user refrains from using or sharing with others unauthorized Paramount's materials in the future. Further, we believe that the entire Internet community benefits when these matters are resolved cooperatively. -

THE SIXTH EXTINCTION: an UNNATURAL HISTORY Copyright © 2014 by Elizabeth Kolbert

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. THE SIXTH EXTINCTION: AN UNNATURAL HISTORY Copyright © 2014 by Elizabeth Kolbert. All rights reserved. For information, address Henry Holt and Co., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010. www.henryholt.com Jacket photograph from the National Museum of Natural History, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution e-ISBN 978-0-8050-9979-9 First Edition: February 2014 If there is danger in the human trajectory, it is not so much in the survival of our own species as in the fulfillment of the ultimate irony of organic evolution: that in the instant of achieving self- understanding through the mind of man, life has doomed its most beautiful creations. —E. O. WILSON Centuries of centuries and only in the present do things happen. —JORGE LUIS BORGES CONTENTS Title Page Copyright Notice Copyright Epigraph Author’s Note Prologue I: The Sixth Extinction II: The Mastodon’s Molars III: The Original Penguin IV: The Luck of the Ammonites V: Welcome to the Anthropocene VI: The Sea Around Us VII: Dropping Acid VIII: The Forest and the Trees IX: Islands on Dry Land X: The New Pangaea XI: The Rhino Gets an Ultrasound XII: The Madness Gene XIII: The Thing with Feathers Acknowledgments Notes Selected Bibliography Photo/Illustration Credits Index About the Author Also by Elizabeth Kolbert AUTHOR’S NOTE Though the discourse of science is metric, most Americans think in terms of miles, acres, and degrees Fahrenheit. -

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

About Endgame

IN ASSOCIATION WITH BLINDER FILMS presents in coproduction with UMEDIA in association with FÍS ÉIREANN / SCREEN IRELAND, INEVITABLE PICTURES and EPIC PICTURES GROUP THE HAUNTINGS BEGIN IN THEATERS MARCH, 2020 Written and Directed by MIKE AHERN & ENDA LOUGHMAN Starring Maeve Higgins, Barry Ward, Risteárd Cooper, Jamie Beamish, Terri Chandler With Will Forte And Claudia O’Doherty 93 min. – Ireland / Belgium – MPAA Rating: R WEBSITE: www.CrankedUpFilms.com/ExtraOrdinary / http://rosesdrivingschool.com/ SOCIAL MEDIA: Facebook - Twitter - Instagram HASHTAG: #ExtraOrdinary #ChristianWinterComeback #CosmicWoman #EverydayHauntings STILLS/NOTES: Link TRAILER: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x1TvL5ZL6Sc For additional information please contact: New York: Leigh Wolfson: [email protected]: 212.373.6149 Nina Baron: [email protected] – 212.272.6150 Los Angeles: Margaret Gordon: [email protected] – 310.854.4726 Emily Maroon – [email protected] – 310.854.3289 Field: Sara Blue - [email protected] - 303-955-8854 1 LOGLINE Rose, a mostly sweet & mostly lonely Irish small-town driving instructor, must use her supernatural talents to save the daughter of Martin (also mostly sweet & lonely) from a washed-up rock star who is using her in a Satanic pact to reignite his fame. SHORT SYNOPSIS Rose, a sweet, lonely driving instructor in rural Ireland, is gifted with supernatural abilities. Rose has a love/hate relationship with her ‘talents’ & tries to ignore the constant spirit related requests from locals - to exorcise possessed rubbish bins or haunted gravel. But! Christian Winter, a washed up, one-hit-wonder rock star, has made a pact with the devil for a return to greatness! He puts a spell on a local teenager- making her levitate. -

Grist Only on Soundcult Extreme Album Review

2/22/2018 Drumcorps – Grist only on Soundcult Extreme Album Review article quote Wanna find something? Drumcorps – Grist September 12, 2007 Fiend Leave a comment electronic, review breakcore, electronic, grindcore Album Reviews Music News Where to Send Promos Become a Editor About Us Copyright Policy Post Types Article Image Link Audio Video Quote Categories electronic metal news review rock Amazon Music Deals! Popular I could say i have a sort of love/hate relationship with grindcore, mostly because when its well made, it’s Kingcrow ‑ Insider completely and utterly awesome, but most of the times its just an amalgam of noise and not in the good sense, December 20, 2013 also i could say i have the same feeling with electronic music in general, so when Aaron Specter‘s Drumcorps no comments pulls this “Grist” saying it’s a mixing of grindcore and breakcore… i tend to take it with a grain of salt. It all starts up with “Botch Up and Die” and it’s pretty grindcore, kinda of a homage to Botch, with the eccentric Dark Tranquility and Sonata guitars over a grind blast beat, its not only amusing but quite groovy, nicely done, “Down” is kinda dance meets Arctica joined forces for Heavy noisecore with distorted samples and guitars into the mix, okkk, “Pig Destroyer Destroyer” has some nice Metal Poker Tournament drumming building to a slowed down chopped distorted noise filled beat … are we making fun of Pig Destroyer?, December 12, 2013 is this supposed to be a compliment or a satire, anyway it all builds up to a distorted guitar breakcore fest, no comments mixing real life drumming with beats and distortion…. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. For The Economistt perpetuating the Patent Office myth, see April 13, 1991, page 83. 2. See Sass. 3. Book publication in 1906. 4.Swirski (2006). 5. For more on eliterary critiques and nobrow artertainment, see Swirski (2005). 6. Carlin, et al., online. 7. Reagan’s first inaugural, January 20, 1981. 8. For background and analysis, see Hess; also excellent study by Lamb. 9. This and following quote in Conason, 78. 10. BBC News, “Obama: Mitt Romney wrong.” 11. NYC cabbies in Bryson and McKay, 24; on regulated economy, Goldin and Libecap; on welfare for Big Business, Schlosser, 72, 102. 12. For an informed critique from the perspective of a Wall Street trader, see Taleb; for a frontal assault on the neoliberal programs of economic austerity and political repression, see Klein; Collins and Yeskel; documentary Walmart. 13. In Kohut, 28. 14. Orwell, 318. 15. Storey, 5; McCabe, 6; Altschull, 424. 16. Kelly, 19. 17. “From falsehood, anything follows.” 18. Calder; also Swirski (2010), Introduction. 19. In The Economist, February 19, 2011: 79. 20. Prominently Gianos; Giglio. 21. The Economistt (2011). 22. For more examples, see Swirski (2010); Tavakoli-Far. My thanks to Alice Tse for her help with the images. Chapter 1 1. In Powers, 137; parts of this research are based on Swirski (2009). 2. Haynes, 19. 168 NOTES 3. In Moyers, 279. 4. Ruderman, 10. 5. In Krassner, 276–77. 6. Green, 57; bottom of paragraph, Ruderman, 179. 7. In Zagorin, 28; next quote 30; Shakespeare did not spare the Trojan War in Troilus and Cressida. -

Lamorinda Weekly Issue 23 Volume 11

Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2018 • Vol. 11 Issue 23 26,000 copies delivered biweekly to Lamorinda homes & businesses 925-377-0977 wwww.lamorindaweekly.comww.lamorindaweekly.com FREE Windy Margerum shows off her winning medals (left). Margerum in long jump (top right); Monte Upshaw, 1954 (lower right). Photos providedprovided Keeping track of Lamorinda long jumpers By John T. Miller hree generations of track and fi eld stars continue to long jump (‘04 and ‘08) – stays active with private coach- Joy and Grace, along with their other siblings Chip and make news in the Lamorinda area. ing, and Joy’s daughter, Acalanes High School grad Windy Merry, plan to honor their father with a Monte Upshaw T Monte Upshaw, the patriarch of the family, Margerum, is off to a fl ying start at UC Berkeley compet- Long Jump Festival to be held at Edwards Stadium next passed away in July and will be honored next year with ing in track and fi eld. Joy’s eldest daughter Sunny is a for- year. The event is being planned to coincide with the Bru- a long jump festival. His eldest daughter Joy continues to mer Central Coast Section champion long jumper whose tus Hamilton Invitational meet on April 27-28. Proceeds excel in Masters track and fi eld competition worldwide; college career at Berkeley was cut short by an Achilles in- will go to benefi t the UC Berkeley track program. a younger daughter Grace – a two-time Olympian in the jury. ... continued on page A12 Advertising Here's to a happy, healthy and homey new year! 1941 Ascot Drive, Moraga 2 bedrooms 710 Augusta Drive, Moraga 2 bedrooms Community Service B4 + den/2 baths, + den, 2 baths, 1,379 sq.ft. -

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

Echo Beatty – 'Tidal Motions' (Icarus Records & Vynilla Vinyl) (Album

Echo Beatty – ‘Tidal Motions’ (Icarus Records & Vynilla Vinyl) (Album release: 28/01/2013 – Single ‘Tidal Motions’: 12/12/2012) The new Ghent-based label Icarus Records aims to be a platform for music that is undefined by musical borders. Antwerp-based duo Echo Beatty’s debut album ‘Tidal Motions’ is the first release on the label, a cooperation with Vynilla Vinyl. The album will be presented in Antwerp (Friday 18/01/13 - Salle Jeanne) and Ghent (Saturday 19/01/13 - Minardschouwburg). Echo Beatty Hailing from Antwerp, Echo Beatty are multi-instrumentalist Jochem Baelus and singer Annelies Van Dinter. It is February 2011, and Echo Beatty is the first-ever band to record an Icarus.fm livesession for Ghent-based radio station Urgent.fm. Consciously and continuously exploring their own musical limits, they use a wide array of homemade instruments, ranging from knitting needles and haircombs to musicboxes, to create their unpredictable and subtle trademark sound. Fragile yet sometimes aggressive. Light in some places, dark in others. Following the release of their first EP ‘Tiny Organs Of Trust’, and a small tour playing venues in Germany, The Netherlands and the Czech Republic, they temporarely move to Montreal in the spring of 2011 to work on new songs. There they join forces with producer Jeff Mc Murrich, known for prior collaborations with artists as Sandro Perri, Owen Pallett and Tindersticks. Tidal Motions Mc Murrich succesfully manages to capture Echo Beatty’s characteristical sound, that can be described as electric folk drenched in a subtle ‘Twin Peaks’’ atmosphere. ‘Tidal Motions’ is Echo Beatty’s very first full album. -

KREVISS Cargo Records Thanks WW DISCORDER and All Our Retail Accounts Across the Greater Vancouver Area

FLAMING LIPS DOWN BY LWN GIRL TROUBLE BOMB ATOMIC 61 KREVISS Cargo Records thanks WW DISCORDER and all our retail accounts across the greater Vancouver area. 1992 was a good year but you wouldn't dare start 1993 without having heard: JESUS LIZARD g| SEBADOH Liar Smash Your Head IJESUS LIZARD CS/CD On The Punk Rock CS/CD On Sebadoh's songwriter Lou Barlow:"... (his) songwriting sticks to your gullet like Delve into some raw cookie dough, uncharted musical and if he ever territory. overcomes his fascination with the The holiday season sound of his own being the perfect nonsense, his time for this baby Sebadoh could be from Jesus Lizard! the next greatest band on this Hallelujah! planet". -- Spin ROCKET FROM THE CRYPT Circa: Now! CS/CD/LP San Diego's saviour of Rock'n'Roll. Forthe ones who Riff-driven monster prefer the Grinch tunes that are to Santa Claus. catchier than the common cold and The most brutal, loud enough to turn unsympathetic and your speakers into a sickeningly repulsive smoldering heap of band ever. wood and wires. A must! Wl Other titles from these fine labels fjWMMgtlllli (roue/a-GO/ are available through JANUARY 1993 "I have a responsibility to young people. They're OFFICE USE ONLY the ones who helped me get where I am today!" ISSUE #120 - Erik Estrada, former CHiPs star, now celebrity monster truck commentator and Anthony Robbins supporter. IRREGULARS REGULARS A RETROSPECT ON 1992 AIRHEAD 4 BOMB vs. THE FLAMING LIPS COWSHEAD 5 SHINDIG 9 GIRL TROUBLE SUBTEXT 11 You Don't Go To Hilltop, You VIDEOPHILTER 21 7" T\ REAL LIVE ACTION 25 MOFO'S PSYCHOSONIC PIX 26 UNDER REVIEW 26 SPINLIST. -

Mapping the Aesthetical-Political Sonic, Master Thesis, © March 2017 Supervisor: Sommerer, Christa, Univ.-Prof

Universität für Künstlerische und Industrielle Gestaltung Linz Institut für Medien Interface Culture SOUNDSREVOLTING:MAPPINGTHE AESTHETICAL-POLITICALSONIC oliver lehner Master Thesis MA supervisor: Sommerer, Christa, Univ.-Prof. Dr. date of approbation: March 2017 signature (supervisor): Linz, 2017 Oliver Lehner: Sounds Revolting: Mapping the Aesthetical-Political Sonic, Master Thesis, © March 2017 supervisor: Sommerer, Christa, Univ.-Prof. Dr. location: Linz ABSTRACT I demand change. As a creator of sound art, I wanted to know what it can do. I tried to find out about the potential field in the overlap between a political aesthetic and a political sonic, between an artis- tic activism and sonic war machines. My point of entry was Steve Goodman’s Sonic Warfare. From there, trajectories unfolded through sonic architectures into an activist philosophy in interactive art. Sonic weapon technology and contemporary sound art practices define a frame for my works. In the end, I could only hint at sonic agents for change. iii CONTENTS i thesis 1 1 introduction 3 1.1 Why sound matters (to me) . 3 1.2 Listening for “New Weapons” . 4 1.3 Sounds of War . 5 1.4 Aesthetics and Politics . 6 2 acoustic weapons 11 2.1 On “Non-lethal” Weapons (NLW) . 11 2.2 A brief history of weaponized sound . 14 2.3 Sonic Battleground Europe . 19 2.4 Civil Sonic Weapons and Counter Measures . 20 3 the art of (sonic) war 23 3.1 Advanced Hyperstition: Goodman’s work after Sonic Warfare . 23 3.2 Artistic Sonic War Machines . 26 3.3 Ultrasound Art and Micropolitics of Frequency . 31 4 the search for sound artivism 37 4.1 Art and Activism .