“A Certain Stigma” of Educational Radio: Judith Waller and “Public Service” Broadcasting Amanda R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio and Television Station Transfers: Adequacy of Supervision Under the Federal Communications Act

Indiana Law Journal Volume 30 Issue 3 Article 6 Spring 1955 Radio and Television Station Transfers: Adequacy of Supervision under the Federal Communications Act Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Communications Law Commons Recommended Citation (1955) "Radio and Television Station Transfers: Adequacy of Supervision under the Federal Communications Act," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 30 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol30/iss3/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES RADIO AND TELEVISION STATION TRANSFERS:. ADEQUACY OF-SUPERVISION UNDER THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS ACT Over five hundred radio and television stations were transferred in a recent twelve month period reflecting the increasing significance of transfers in regulation of the industry.1 While the history of radio regu- lation traces back to 1910,2 the first legislation controlling transfers was the Radio Act of 1927 which required "the consent in writing of the licensing authority."3 The Communications Act of 1934 re-enacted this provision and added the "public interest" criterion as a basis for judging transfers.4 Under this vague statutory mandate,, the FCC has empha- sized a number of factors in approving or disapproving transfer applica- 1. For purposes of this Note, "transfer" will refer to transfer and assignment of stations (which naturally includes the license), and transfers of construction permits. -

Offensive Language Spoken on Popular Morning Radio Programs Megan Fitzgerald

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Offensive Language Spoken on Popular Morning Radio Programs Megan Fitzgerald Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION OFFENSIVE LANGUAGE SPOKEN ON POPULAR MORNING RADIO PROGRAMS By MEGAN FITZGERALD A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Megan Fitzgerald defended on October 31, 2007. Barry Sapolsky Professor Directing Dissertation Colleen Kelley Outside Committee Member Jay Rayburn Committee Member Gary Heald Committee Member Steven McClung Committee Member Approved: Stephen McDowell, Chair, Communication John K. Mayo, Dean, Communication The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Patrick and Kathleen Fitzgerald. Thank you for supporting all that I do—even when I wanted to grow up to be the Pope. By watching you, I learned the power of teaching by example. And, you set the best. Thank you. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation was completed under the guidance of my major professor, Dr. Barry Sapolsky. Dr. Sapolsky not only served as my major professor, but also as a mentor throughout my entire graduate program. He was a constant source of encouragement, motivation, and, at times, realism. In addition to serving on my committee, he also gave me the opportunity to work in the Communication Research Center. -

Groping in the Dark : an Early History of WHAS Radio

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2012 Groping in the dark : an early history of WHAS radio. William A. Cummings 1982- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cummings, William A. 1982-, "Groping in the dark : an early history of WHAS radio." (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 298. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/298 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GROPING IN THE DARK: AN EARLY HISTORY OF WHAS RADIO By William A. Cummings B.A. University of Louisville, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2012 Copyright 2012 by William A. Cummings All Rights Reserved GROPING IN THE DARK: AN EARLY HISTORY OF WHAS RADIO By William A. Cummings B.A., University of Louisville, 2007 A Thesis Approved on April 5, 2012 by the following Thesis Committee: Thomas C. Mackey, Thesis Director Christine Ehrick Kyle Barnett ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my grandfather, Horace Nobles. -

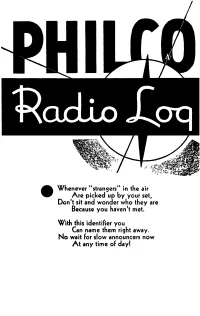

Philco Radio Log 1934

Whenever "strangers" in the air Are picked up by your set, Don't sit and wonder who they are Because you haven't met. With this identifier you Can name them right away. No wait for slow announcers now At any time of day! 50 75 100 150 200 250 300 500 750 1000 POWER 1500 2000 2500 1000 10000 15000 25000 50000 F G H I J K L M N 0 CODE P Q R 5 T U V W There are only 97 numbers on YOUR dial to accommodate more than 700 radio stations of North Amer ica. Stations at each number are listed MAP-LIKE beside 97 blank spaces. The 97 groups are in exact order, so, YOUR dial number recorded every 5th, or 10th, space enables you to estimate those skipped. To identify those heard by chance, station announcements will seldom be necessary. You can expect to hear stations of greater power, from greater distances. Note the letter at the extreme right and code above. *C:olumbla (WABC:) tNallonal Red (WEAF) .J.Natlonal Blue (WlZ) :J:Natlonal Red OR Blue Network Revision 40 1933-BY HAYNES' RADIO LOG Winter 1933 161 WEST HARRISON ST. CHICAGO, ILLINOIS WESTERN MIDDLE WESTERN Kilo D' I N CENTRAL EASTER'N WtI811 •• Ore •• Cal •• Utah. Etc. Minn., la., Neb., ~o .• Tez., Etc 14 o. Ilt, Mfch., OhiO, Tenn., Etc. MasS., N. Y., Pa .• N. Co.Btc. CFQC S.:skatoon. Sask ..... M 540 'CKLW Windsor-Detroit .... S ~~~~ ~~~~!lft~~b~e?::;~:·:~ r~~~RK:I~:"~~k~J.~~~: .~ 558---- ·WKRC Cincinnati. Ohlo...• O ·:::~lWa'te~b~ilvi·:::::~ *KLZ Den ver. -

A Wavelength for Every Network: Synchronous Broadcasting and National Radio in the United States, 1926–1932 Michael J

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Communication and Journalism Faculty Communication and Journalism Scholarship 2007 A Wavelength for Every Network: Synchronous Broadcasting and National Radio in the United States, 1926–1932 Michael J. Socolow University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cmj_facpub Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Radio Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Socolow, Michael J., "A Wavelength for Every Network: Synchronous Broadcasting and National Radio in the United States, 1926–1932" (2007). Communication and Journalism Faculty Scholarship. 1. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cmj_facpub/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication and Journalism Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Wavelength for Every Network: Synchronous Broadcasting and National Radio in the United States, 1926-1932 Author(s): Michael J. Socolow Source: Technology and Culture, Vol. 49, No. 1 (Jan., 2008), pp. 89-113 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press and the Society for the History of Technology Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40061379 Accessed: 07-06-2016 21:28 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. -

Radio Program Controls: a Network of Inadequacy

RADIO PROGRAM CONTROLS: A NETWORK OF INADEQUACY " [Tihe troubles of representative government . go back to a common source: to the failure of self-governing people to trans- cend their casual experience and their prejudice, by inventing, creating, and organizing a machinery of knowledge." t RADIo broadcasting is unique among the media of mass communication in that, while the reach of its facilities is unsurpassed,' their number is limited ultimately by the finite nature of the broadcast spectrum - and not by the availability of finance capital.3 Conditioned in its every aspect by this physical circumscription, national policy toward radio 4 has abandoned the theoretically free competition guaranteed other vehicles of expression 11 and has established a licensing system restricting the number of stations, tNVATE Lipp-mAN, PUBLIC OpiNiox 364-5 (1922). 1. Ninety-eight per cent of the people of the United States are within range of at least one of the more than 1400 operating or authorized stations, WnrrE, TiE Atox- CAN RAnio 204 (1947), while approximately four-fifths of the country's homes, it may be estimated, are equipped with radios. SIXTEENTH CENSUS, HousINo, Vol. I1, pt. I, p. 28 (1943). The picture is darkened by the fact that 5,575 of the cities of 1,000 or more population have no local stations and, accordingly, can receive only programs broadcast to extensive areas and not aimed at the needs of particular localities. While frequency modulation (FM) makes technically possible indigenous coverage of these communities, construction expense forces the prediction that most small towns will continue to receive only outside treatment of local news. -

Richard Flury Catalogue of Works

1 Richard Flury Catalogue of Works (For the printed catalogue, see Chris Walton: Richard Flury. The Life and Music of a Swiss Romantic. London: Toccata Press, 2017) Abbreviations Performing forces pic – piccolo; fl – flute; afl – alto flute; ob – oboe; eng hn – cor anglais; cl – clarinet; bcl – bass clarinet; s-sax – soprano saxophone; a-sax – alto saxophone; bar-sax – baritone saxophone; b-sax – bass saxophone; bn – bassoon; cbn – contrabassoon; hn – horn; tpt – trumpet; trbn – trombone; btrbn – bass trombone; flugelhn – flugelhorn; a-hn – alto horn [in E-flat]; t-hn – tenor horn [in B flat]; bar-hn – baritone horn; tb – tuba; timp – timpani; cast – castanets; cym – cymbal(s); glock – glockenspiel; tamb – tambourine; tamt – tam-tam; trgl – triangle; xyl – xylophone; hp – harp; org – organ; pf – piano; cel – celeste; vn – violin; va – viola; vc – cello; db – double bass; str – strings; S – soprano; Mez – mezzo- soprano; A – alto, contralto; T – tenor; Bar – baritone; B – bass The ‘alto horn (here ‘a-hn’) is here a Saxhorn in E flat, the tenor horn (here ‘t-hn’) is in B flat. Where ‘hn’ is used below on its own, it refers only to the French horn. Where Flury’s band music requires instruments such as a piccolo in D flat or a metal clarinet, this is clearly marked as such. Other abbreviations FP – first performance Instr. – instrumentation Publ. – publication cond. – conducted by Operas Eine florentinische Tragödie. Opera in one act Libretto: Oscar Wilde’s play A Florentine Tragedy in the German translation by Max Meyerfeld, slightly abridged by Richard Flury 1926–28 (date of completion: 14 December 1928) Dramatis personae: Bianca – soprano Simone – baritone Guido – tenor Date and place: Florence, 1500s Instr.: 2 fl (2+pic), 2 ob, 2 cl, 2 bn – 4 hn, 2 tpt, 3 trbn – timp, bass drum, cast, cym, glock, side-drum, tamb, tamt, trgl – hp – str FP: 9 April 1929 in the Solothurn City Theatre. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

70-14,102 STEBBINS, Gene R., 1934- LISTENER-SPONSORED RADIO: THE PACIFICA STATIONS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 • Mass Communications University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright by Gene R. Stebbins 1970 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED LISTENER-SPONSORED RADIO: THE PACIFICA STATIONS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gene R. Stebbins, B.A., M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Apposed b Adviser rtment of ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS No work such as the present one could be under taken without substantial help and assistance from a great number of people. The author is deeply indebted to many persons, including the followingr the Board of Directors of Pacifica Foundation for permission to do research in the records and papers of Pacifica and KPFA, the many persons now associated with KPFA who contri buted valuable information, the many former KPFA staff members who consented to lengthy interviews, and a number of persons who by correspondence contributed sig nificant information, including Mr. Norman Jorgensen, attorney," Mr. Johnson D. Hill? and Mrs. Joy Hill. To two women who have never met, but without whom this work would never have been possible, go the author' deepest appreciations Mrs. Vera Hopkins, Secretary to Pacifica Foundation, whose patience and assistance far exceeded that asked; and the author's wife Judy, whose proofreading and suggestions were invaluable. ii Finally, the author wishes to acknowledge the persons noted in these pages and many who are not whose devotion, patience, and perseverence are responsible for the existence of the Pacifica stations. -

Programming Live Local Radio in the 1930S: WDZ Reaches Rural Illinois

Programming Live Local Radio in the 1930s: WDZ Reaches Rural Illinois By Stephen D. Perry, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Communication Illinois State University Submitted to BEA History Division (Open Competition) 1999 Convention – Las Vegas, NV Running Head: LIVE LOCAL RADIO Contact: Stephen Perry ISU Dept. of Communication Box 4480 Normal, IL 61790-4480 [email protected] (309) 438-7339 Fax: (309) 438-3048 Live Local Radio 2 Programming Live Local Radio in the 1930s: WDZ Reaches Rural Illinois Abstract Though vast in quantity, little study has pursued the types of content programmed by the independent radio station. This study examines the first decade of full-time programming at rural WDZ, examining artist acquisition, financing, and genres. WDZ moved from a haphazard open- door policy to a more professional orientation. The station eventually made extensive efforts to reach out into communities it served, promoting both the station and the livelihood of on-air performers through paid concert appearances. Live Local Radio 3 Programming Live Local Radio in the 1930s: WDZ Reaches Rural Illinois Despite its dominance of America’s waking hours and public consciousness from 1922 until its apotheosis in television in the early 1950s (and despite the attention that media such as film, television, and the press have received academically), radio remains a dark and fading memory somewhere between vaudeville and I Love Lucy—without the benefit of cable-channel reruns (Hilmes, 1997, xiv). Much of what is known about radio’s early decades comes from information available through the dominant and centralized sources, such as the NBC and CBS networks and the corporate parents of early networks, AT&T, RCA, GE, and Westinghouse. -

![National Broadcasting Company History Files [Finding Aid]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6659/national-broadcasting-company-history-files-finding-aid-11226659.webp)

National Broadcasting Company History Files [Finding Aid]

NBC: A Finding Aid to the National Broadcasting Company History Files at the Library of Congress, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1999 Revised 2010 March Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsrs/mbrsrs.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsrs/eadmbrs.rs000001 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2002660093 Index to the collection completed by Seth Morris, Sam Brylawski, Jan McKee, Bryan Cornell, and Gene DeAnna, 1995. Finding aid expanded by Gail Sonnemann with the assistance of Kathleen B. Miller. Collection Summary Title: National Broadcasting Company history files Dates: 1922-1986 Creator: National Broadcasting Company Extent: 1966 folders of manuscript and published papers Language: Collection material in English Location: Recorded Sound Reference Center, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: The National Broadcasting Company History files document the activities of the first national broadcasting network in the United States. The collection includes memoranda, correspondence, speeches, reports, policy statements, and pamphlets covering the creation of the network, its growth in the field of radio, and its subsequent expansion into television broadcasting. Location: NBC history files, Folders 1-1966 Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Dunham, Corydon B., 1927- Goodman, Julian, 1922- Lohr, Lenox R. -

Hasse KAHNS: Egon KAISER

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Hasse KAHNS: Hasse Kahn -v; Göte Wilhelmsson -p; Lasse Karlsson -g; Ingvar Berggren -b; Sten Sköld -d; recorded March 16, 1949 in Stockholm 69335 MEAN TO ME 2.19 Aircheck ------------------------------------------ Egon KAISER: Egon Kaiser und sein Orchester; Refrain: Paul Erdtmann; recorded April 1932 in Berlin 105155 DEINE BEINE 2.45 C1945 Kristall 3284 Tanzorchester Egon Kaiser; Refraingesang: Paul Dorn; recorded March 1933 in Berlin 106083 JEDER MACHT MAL EINE DUMMHEIT 2.31 5641 Polydor 17087 aus dem Tonfilm "Skandal in Budapest" Egon Kaiser Tanzorchester mit deutschem Refraingesang: Paul Dorn; recorded August 1933 in Berlin 105196 WENN ICH SO KÖNNTE WIE ICH MÖCHTE 3.09 5531 BR Grammophon 10159 105200 MACH' DIE AUGEN ZU UND TRÄUM' MIT MIR VON LIEBE 3.04 5532 BR --- Tanzorchester Egon Kaiser; Refraingesang: Erwin Hartung; recorded December 1933 in Berlin 106052 WENN ES EIN GLÜCK GIBT 3.12 5627 Polydor 17087 Tanzorchester Egon Kaiser; Paul Dorn -Refraingesang; recorded January 1934 in Berlin 106053 NUR DU BRINGST MIR DAS GLÜCK INS HAUS 3.04 2305 Grammophon 10163 Egon Kaiser mit seinem Tanzorchester; Refraingesang: Inge Haff; recorded January 1934 in Berlin 107538 EINMAL EINE GROSSE DAME SEIN 2.55 2504 Gram 10 163 aus dem gleichnamigen Tonfilm Tanzorchester Egon Kaiser; Refraingesang: Max Mensing; Leitung: Walter Ulfig; recorded March 1934 in Berlin 106087 EIN WENIG LEICHTSINN -

A History of Educational Radio in Chicago with Emphasis on WBEZ-FM, 1920-1960

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1991 A History of Educational Radio in Chicago with Emphasis on WBEZ-FM, 1920-1960 Jerry J. Field Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Field, Jerry J., "A History of Educational Radio in Chicago with Emphasis on WBEZ-FM, 1920-1960" (1991). Dissertations. 2273. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2273 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1991 Jerry J. Field A History of Educational Radio In Chicago With Emphasis on WBEZ-FM: 1920-1960 by Jerry J. Field A Dissertation Proposal Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Education of Loyola Uni_versity of_ Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education (Ed.D.) MAY 1991 Jerry J. Field Loyola University of Chicago A HISTORY OF EDUCATIONAL RADIO IN CHICAGO WITH EMPHASIS ON WBEZ-FM: 1920-1960 The Chicago Board of Education was considered one of the pioneers in the use of educational radio in the nation. How radio programs were used by the Chicago Board of Education during the period of 1920 through 1960 is the focus of the dissertation. The Board's use of radio programs as a supplement to the existing lessons was unique to the teaching curriculum.