Radio Program Controls: a Network of Inadequacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glenn Miller 1939 the Year He Found the Sound

GLENN MILLER 1939 THE YEAR HE FOUND THE SOUND Dedicated to the Glenn Miller Birthpace Society June 2019 Prepared by: Dennis M. Spragg Glenn Miller Archives Alton Glenn Miller (1904-1944) From Glenn Miller Declassified © 2017 Dennis M. Spragg Sound Roots Glenn Miller was one of the foremost popular music celebrities of the twentieth century. The creative musician and successful businessman was remarkably intuitive and organized, but far from perfect. His instincts were uncanny, although like any human being, he made mistakes. His record sales, radio popularity, and box-office success at theaters and dance halls across the nation were unsurpassed. He had not come to fame and fortune without struggle and was often judgmental and stubborn. He had remarkable insight into public taste and was not afraid to take risks. To understand Miller is to appreciate his ideals and authenticity, essential characteristics of a prominent man who came from virtually nothing. He sincerely believed he owed something to the nation he loved and the fellow countrymen who bought his records. The third child of Lewis Elmer Miller and Mattie Lou Cavender, Alton Glen Miller was born March 1, 1904, at 601 South 16th Street in Clarinda, a small farming community tucked in the southwest corner of Iowa. Miller’s middle name changed to Glenn several years later in Nebraska. His father was an itinerant carpenter, and his mother taught school. His older brother, Elmer Deane, was a dentist. In 1906 Miller’s father took his family to the harsh sand hills of Tryon, Nebraska, near North Platte. The family moved to Hershey, Nebraska, in the fall of 1912 and returned to North Platte in July 1913, where Glenn’s younger siblings John Herbert and Emma Irene were born. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

CTE Preschool Parent Handbook

CTE Preschool 3 Educational Dr. Essex Jct., VT 05452 (802) 857-7459 Parent Handbook The Center for Technology, Essex Preschool is a lab school operated by a certified head teacher and high school students in the Human Services Program. The schedule is as follows: Tuesday/ Thursday 9:40-11:40 4-5yr olds Tuesday/ Thursday 12:30-2:00 3-4yr olds Wednesday/ Friday 9:40-11:40 4-5yr olds CTE Preschool admits children and employees of any race, religion, disability, color, gender, sexual orientation, and national/ ethnic background. This program is open to children with a wide range of needs. We are a learning facility and if our program can meet the needs of the child with the staff that we have available we are happy to do so. We strive to meet the needs of all children that attend our program. In rare circumstances if our program can not meet the needs of a child and/or the child has an issue that is causing harm to themselves or others and can not be resolved, the child may be asked to leave the program. Fees: There is a $10 non-refundable registration fee. Each class is $5/ day. Payments shall be made monthly or yearly. A notice of payments due will be posted monthly. The purpose of this program is to train high school and adult students for the field of child care. The philosophy of the program is to give the students practical experiences in working with young children. The theory is that one learns best by doing. -

CONTENTS Hearing South American Stations, Uruguay 2 British War News Broadcasts 5 Letters to the Technical Editor, B

'-, ._.RA._-. fflee I grgi ro- :. The .411 -Wave Radio Log Authority November 1939 No. 133 CONTENTS Hearing South American Stations, Uruguay 2 British War News Broadcasts 5 Letters To The Technical Editor, B. Francis Dashiell. 7 Radexing With the Radexers, by Ray LaRocque 11 Turner Dial Says- 16 Among The Clubs 16 Video Varieties, Television 17 The Radex Club 18 DXers' Picture Gallery 20 On The West Coast, by Anthonynthony C. Tarr 21 Ham Hounding, by Hugh Hunter?? 25 Amateur Calls Heard 30 Canada's Friendly Station, by John Beardall, CFCO 32 High Frequency Globe Trotting, by Ray LaRocque 35 Shortwave Broadcasting Stations 4q. DXers' Appointment Calendar 53 Radio Stations of the World 54 Applications to the FCC 62 The Month's Changes in Station Data 63 North American Broadcasting Stations by Frequencies 64 The Saine List Arranged by Locations 84 And By Call Letters 90 FIFTEEN ARTICLES SEVEN INDEXES RRSS RADEX READERS SHOPPING SERVICE OFFERS YOU '- r THE NEW ' F HALLICRAFTERS SKYRIDER DEFIANT SX-24 3 BAND RANGE. Tunes from 540 kcs. to 43500 kcs. in SX-24 - 1939 four bands. Band 1, 540 to 1730 kcs. Band 2, 1700 to 5100 kcs. Band 3, 5000 to 15700 kcs. Band 4, 15200 to 43500 kcs. Skyrider Defiant BAND SPREAD. The band spread dial is calibrated so Cash that the operator may determine the frequency of the J $69.50 Price signals to which he listens in any of the amateur bands. ' The outer edge of the dial is marked off in 100 divisions for additional ease in logging and locating stations. -

Radio and Television Station Transfers: Adequacy of Supervision Under the Federal Communications Act

Indiana Law Journal Volume 30 Issue 3 Article 6 Spring 1955 Radio and Television Station Transfers: Adequacy of Supervision under the Federal Communications Act Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Communications Law Commons Recommended Citation (1955) "Radio and Television Station Transfers: Adequacy of Supervision under the Federal Communications Act," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 30 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol30/iss3/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES RADIO AND TELEVISION STATION TRANSFERS:. ADEQUACY OF-SUPERVISION UNDER THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS ACT Over five hundred radio and television stations were transferred in a recent twelve month period reflecting the increasing significance of transfers in regulation of the industry.1 While the history of radio regu- lation traces back to 1910,2 the first legislation controlling transfers was the Radio Act of 1927 which required "the consent in writing of the licensing authority."3 The Communications Act of 1934 re-enacted this provision and added the "public interest" criterion as a basis for judging transfers.4 Under this vague statutory mandate,, the FCC has empha- sized a number of factors in approving or disapproving transfer applica- 1. For purposes of this Note, "transfer" will refer to transfer and assignment of stations (which naturally includes the license), and transfers of construction permits. -

“A Certain Stigma” of Educational Radio: Judith Waller and “Public Service” Broadcasting Amanda R

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Communication, College of Publications 1-1-2017 “A Certain Stigma” of Educational Radio: Judith Waller and “Public Service” Broadcasting Amanda R. Keeler Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. Critical Studies in Media Communication, Vol. 34, No. 5 (2017): 495-508. DOI. © 2017 Taylor & Francis Group. Used with permission. Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Publications/Department of Communication This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; but the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation below. Critical Studies in Media Communication, Vol. 34, No. 5 (2017): 495-508. DOI. This article is © Taylor & Francis (Routledge) and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e- Publications@Marquette. Taylor & Francis (Routledge) does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Taylor & Francis (Routledge). “A certain stigma” of educational radio: Judith Waller and “public service” broadcasting Amanda Keeler Department of Digital Media and Performing Arts, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI Abstract This paper explores Judith Waller’s radio programming philosophy over her career that began in 1922 at WMAQ Chicago. In the 1940s, representing the interests of her employer NBC, Waller began to use the phrase “public service” as a way to break free of the “stigma” of educational radio. The concept of public service programming shifted during the 1930s and 1940s in the US, redefined and negotiated in response to assumptions about radio listeners, the financial motivations of commercial radio, and Federal Communications Commission rulings. -

Offensive Language Spoken on Popular Morning Radio Programs Megan Fitzgerald

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Offensive Language Spoken on Popular Morning Radio Programs Megan Fitzgerald Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION OFFENSIVE LANGUAGE SPOKEN ON POPULAR MORNING RADIO PROGRAMS By MEGAN FITZGERALD A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Megan Fitzgerald defended on October 31, 2007. Barry Sapolsky Professor Directing Dissertation Colleen Kelley Outside Committee Member Jay Rayburn Committee Member Gary Heald Committee Member Steven McClung Committee Member Approved: Stephen McDowell, Chair, Communication John K. Mayo, Dean, Communication The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Patrick and Kathleen Fitzgerald. Thank you for supporting all that I do—even when I wanted to grow up to be the Pope. By watching you, I learned the power of teaching by example. And, you set the best. Thank you. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation was completed under the guidance of my major professor, Dr. Barry Sapolsky. Dr. Sapolsky not only served as my major professor, but also as a mentor throughout my entire graduate program. He was a constant source of encouragement, motivation, and, at times, realism. In addition to serving on my committee, he also gave me the opportunity to work in the Communication Research Center. -

Detroit's Thanksgiving Day Tradition

DETROIT’S THANKSGIVING DAY TRADITION It was, legend says, a typically colorful, probably chilly, November day in 1622 that Pilgrims and Native Americans celebrated the new world's bounty with a sumptuous feast. They sat together at Plymouth Plantation (they spelled it Plimouth) in Massachusetts, gave thanks for the goodness set before them, then dined on pumpkin pie, sweet potatoes, maize, cranberry sauce, turkey and who knows what else. Actually, fish was just as predominant a staple. And history books say pumpkin pie really debuted a year later. But regardless of the accuracy of the details, that's how Thanksgiving Day is seen by Americans -- except Detroiters. They may have most of the same images as everyone else, but with a new twist that began in 1934. That's when Detroiters and their outstate Michigan compatriots found themselves at the dawn of an unplanned behavior modification, courtesy of George A. "Dick" Richards, owner of the city's new entry in the National Football League: The Detroit Lions. Larry Paladino, Lions Pride, 1993 Four generations of Detroiters have been a proud part of the American celebration of Thanksgiving. The relationship between Detroit and Thanksgiving dates back to 1934 when owner G.A. Richards scheduled a holiday contest between his first-year Lions and the Chicago Bears. Some 75 years later, fans throughout the State of Michigan have transformed an annual holiday event into the single greatest tradition in the history of American professional team sports. Indeed, if football is America’s passion, Thanksgiving football is Detroit’s passion. DETROIT AND THANKSGIVING DAY No other team in professional sports can claim to be as much a part of an American holiday as can the Detroit Lions with Thanksgiving. -

Groping in the Dark : an Early History of WHAS Radio

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2012 Groping in the dark : an early history of WHAS radio. William A. Cummings 1982- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cummings, William A. 1982-, "Groping in the dark : an early history of WHAS radio." (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 298. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/298 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GROPING IN THE DARK: AN EARLY HISTORY OF WHAS RADIO By William A. Cummings B.A. University of Louisville, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2012 Copyright 2012 by William A. Cummings All Rights Reserved GROPING IN THE DARK: AN EARLY HISTORY OF WHAS RADIO By William A. Cummings B.A., University of Louisville, 2007 A Thesis Approved on April 5, 2012 by the following Thesis Committee: Thomas C. Mackey, Thesis Director Christine Ehrick Kyle Barnett ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my grandfather, Horace Nobles. -

Connect with Us

DIGITAL CHANNEL GUIDE Contact us at 496-5800 or visit www.waitsfieldcable.com for more information. HD CHANNELS 233 The Tennis Channel HD Standard HD 288 E! HD Standard HD 203 WCAX (CBS) HD Standard HD 236 The Outdoor Channel HD Preferred HD 290 Comedy Central HD Standard HD 204 WVNY (ABC) HD Standard HD 237 Universal Sports Network HD Standard HD 291 Bravo HD Preferred HD 205 WPTZ (NBC) HD Standard HD 239 Fox News Channel HD Standard HD 295 Syfy HD Preferred HD 206 CBMT (CBC) HD Standard HD 240 CNBC HD Standard HD 299 FXX HD Preferred HD 207 WFFF (FOX) HD Standard HD 241 MSNBC HD Standard HD 301 The Discovery Channel HD Standard HD 209 WETK (PBS) HD Standard HD 242 CNN HLN News and Views HD Standard HD 302 History HD Standard HD 213 USA HD Standard HD 243 CNN HD Standard HD 303 Animal Planet HD Standard HD 214 FX Networks HD Standard HD 256 The Disney Channel HD Standard HD 304 National Geographic HD Standard HD 215 Spike TV HD Standard HD 257 Disney XD HD Standard HD 306 The Science Channel HD Preferred HD 216 TBS HD Standard HD 258 Cartoon Network HD Standard HD 307 Biography HD Preferred HD 217 TNT HD Standard HD 259 Nickelodeon HD Standard HD 309 NASA HD Preferred HD 221 Major League Baseball 268 ABC Family HD Standard HD 311 American Movie Classics HD Standard HD Network HD Standard HD 270 Lifetime Network HD Standard HD 312 Lifetime Movie Network HD Standard HD 222 NBC Sports Network HD Standard HD 274 Women’s Entertainment HD Preferred HD 315 Independent Film Channel HD Preferred HD 223 NFL Network HD Standard HD 276 Food Network -

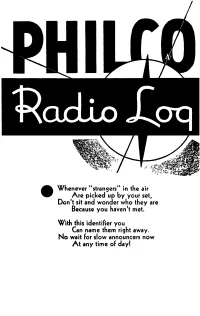

Philco Radio Log 1934

Whenever "strangers" in the air Are picked up by your set, Don't sit and wonder who they are Because you haven't met. With this identifier you Can name them right away. No wait for slow announcers now At any time of day! 50 75 100 150 200 250 300 500 750 1000 POWER 1500 2000 2500 1000 10000 15000 25000 50000 F G H I J K L M N 0 CODE P Q R 5 T U V W There are only 97 numbers on YOUR dial to accommodate more than 700 radio stations of North Amer ica. Stations at each number are listed MAP-LIKE beside 97 blank spaces. The 97 groups are in exact order, so, YOUR dial number recorded every 5th, or 10th, space enables you to estimate those skipped. To identify those heard by chance, station announcements will seldom be necessary. You can expect to hear stations of greater power, from greater distances. Note the letter at the extreme right and code above. *C:olumbla (WABC:) tNallonal Red (WEAF) .J.Natlonal Blue (WlZ) :J:Natlonal Red OR Blue Network Revision 40 1933-BY HAYNES' RADIO LOG Winter 1933 161 WEST HARRISON ST. CHICAGO, ILLINOIS WESTERN MIDDLE WESTERN Kilo D' I N CENTRAL EASTER'N WtI811 •• Ore •• Cal •• Utah. Etc. Minn., la., Neb., ~o .• Tez., Etc 14 o. Ilt, Mfch., OhiO, Tenn., Etc. MasS., N. Y., Pa .• N. Co.Btc. CFQC S.:skatoon. Sask ..... M 540 'CKLW Windsor-Detroit .... S ~~~~ ~~~~!lft~~b~e?::;~:·:~ r~~~RK:I~:"~~k~J.~~~: .~ 558---- ·WKRC Cincinnati. Ohlo...• O ·:::~lWa'te~b~ilvi·:::::~ *KLZ Den ver.