Radio and Television Broadcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 22, 2015, Meeting with Southern

Southern Nuclear Operating Company STANDARD EMERGENCY PLAN ANNEX for Vogtle Electric Generating Plant Units 1 and 2 FINAL DRAFT DRAFT VEGP UNITS 1 AND 2 ANNEX DRAFT Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction (SEP) ...................................................................................................................3 1.1 Facility Description ............................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Emergency Planning Zones (SEP J.5) ............................................................................................... 3 1.3 State of Georgia (SEP A.2.2) ............................................................................................................. 3 1.4 State of South Carolina (SEP A.2.3) .................................................................................................. 5 1.5 Local Organizations (SEP A.2.4, B.6.1) ............................................................................................ 6 1.6 24-Hour Staffing (SEP F.1.2) ............................................................................................................ 6 1.7 Department of Energy (DOE) – Savannah River Site (SRS) (SEP A.1.4) ........................................ 7 Figure 1.1.A – Location and Vicinity Map ................................................................................................. 8 Figure 1.1.B - Vogtle Electric Generating Plant Site Plan ........................................................................ -

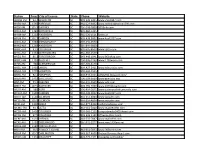

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

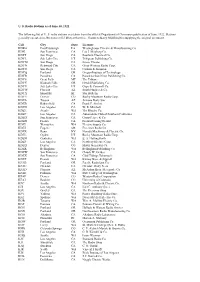

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

CTE Preschool Parent Handbook

CTE Preschool 3 Educational Dr. Essex Jct., VT 05452 (802) 857-7459 Parent Handbook The Center for Technology, Essex Preschool is a lab school operated by a certified head teacher and high school students in the Human Services Program. The schedule is as follows: Tuesday/ Thursday 9:40-11:40 4-5yr olds Tuesday/ Thursday 12:30-2:00 3-4yr olds Wednesday/ Friday 9:40-11:40 4-5yr olds CTE Preschool admits children and employees of any race, religion, disability, color, gender, sexual orientation, and national/ ethnic background. This program is open to children with a wide range of needs. We are a learning facility and if our program can meet the needs of the child with the staff that we have available we are happy to do so. We strive to meet the needs of all children that attend our program. In rare circumstances if our program can not meet the needs of a child and/or the child has an issue that is causing harm to themselves or others and can not be resolved, the child may be asked to leave the program. Fees: There is a $10 non-refundable registration fee. Each class is $5/ day. Payments shall be made monthly or yearly. A notice of payments due will be posted monthly. The purpose of this program is to train high school and adult students for the field of child care. The philosophy of the program is to give the students practical experiences in working with young children. The theory is that one learns best by doing. -

CONTENTS Hearing South American Stations, Uruguay 2 British War News Broadcasts 5 Letters to the Technical Editor, B

'-, ._.RA._-. fflee I grgi ro- :. The .411 -Wave Radio Log Authority November 1939 No. 133 CONTENTS Hearing South American Stations, Uruguay 2 British War News Broadcasts 5 Letters To The Technical Editor, B. Francis Dashiell. 7 Radexing With the Radexers, by Ray LaRocque 11 Turner Dial Says- 16 Among The Clubs 16 Video Varieties, Television 17 The Radex Club 18 DXers' Picture Gallery 20 On The West Coast, by Anthonynthony C. Tarr 21 Ham Hounding, by Hugh Hunter?? 25 Amateur Calls Heard 30 Canada's Friendly Station, by John Beardall, CFCO 32 High Frequency Globe Trotting, by Ray LaRocque 35 Shortwave Broadcasting Stations 4q. DXers' Appointment Calendar 53 Radio Stations of the World 54 Applications to the FCC 62 The Month's Changes in Station Data 63 North American Broadcasting Stations by Frequencies 64 The Saine List Arranged by Locations 84 And By Call Letters 90 FIFTEEN ARTICLES SEVEN INDEXES RRSS RADEX READERS SHOPPING SERVICE OFFERS YOU '- r THE NEW ' F HALLICRAFTERS SKYRIDER DEFIANT SX-24 3 BAND RANGE. Tunes from 540 kcs. to 43500 kcs. in SX-24 - 1939 four bands. Band 1, 540 to 1730 kcs. Band 2, 1700 to 5100 kcs. Band 3, 5000 to 15700 kcs. Band 4, 15200 to 43500 kcs. Skyrider Defiant BAND SPREAD. The band spread dial is calibrated so Cash that the operator may determine the frequency of the J $69.50 Price signals to which he listens in any of the amateur bands. ' The outer edge of the dial is marked off in 100 divisions for additional ease in logging and locating stations. -

Connect with Us

DIGITAL CHANNEL GUIDE Contact us at 496-5800 or visit www.waitsfieldcable.com for more information. HD CHANNELS 233 The Tennis Channel HD Standard HD 288 E! HD Standard HD 203 WCAX (CBS) HD Standard HD 236 The Outdoor Channel HD Preferred HD 290 Comedy Central HD Standard HD 204 WVNY (ABC) HD Standard HD 237 Universal Sports Network HD Standard HD 291 Bravo HD Preferred HD 205 WPTZ (NBC) HD Standard HD 239 Fox News Channel HD Standard HD 295 Syfy HD Preferred HD 206 CBMT (CBC) HD Standard HD 240 CNBC HD Standard HD 299 FXX HD Preferred HD 207 WFFF (FOX) HD Standard HD 241 MSNBC HD Standard HD 301 The Discovery Channel HD Standard HD 209 WETK (PBS) HD Standard HD 242 CNN HLN News and Views HD Standard HD 302 History HD Standard HD 213 USA HD Standard HD 243 CNN HD Standard HD 303 Animal Planet HD Standard HD 214 FX Networks HD Standard HD 256 The Disney Channel HD Standard HD 304 National Geographic HD Standard HD 215 Spike TV HD Standard HD 257 Disney XD HD Standard HD 306 The Science Channel HD Preferred HD 216 TBS HD Standard HD 258 Cartoon Network HD Standard HD 307 Biography HD Preferred HD 217 TNT HD Standard HD 259 Nickelodeon HD Standard HD 309 NASA HD Preferred HD 221 Major League Baseball 268 ABC Family HD Standard HD 311 American Movie Classics HD Standard HD Network HD Standard HD 270 Lifetime Network HD Standard HD 312 Lifetime Movie Network HD Standard HD 222 NBC Sports Network HD Standard HD 274 Women’s Entertainment HD Preferred HD 315 Independent Film Channel HD Preferred HD 223 NFL Network HD Standard HD 276 Food Network -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Radio Program Controls: a Network of Inadequacy

RADIO PROGRAM CONTROLS: A NETWORK OF INADEQUACY " [Tihe troubles of representative government . go back to a common source: to the failure of self-governing people to trans- cend their casual experience and their prejudice, by inventing, creating, and organizing a machinery of knowledge." t RADIo broadcasting is unique among the media of mass communication in that, while the reach of its facilities is unsurpassed,' their number is limited ultimately by the finite nature of the broadcast spectrum - and not by the availability of finance capital.3 Conditioned in its every aspect by this physical circumscription, national policy toward radio 4 has abandoned the theoretically free competition guaranteed other vehicles of expression 11 and has established a licensing system restricting the number of stations, tNVATE Lipp-mAN, PUBLIC OpiNiox 364-5 (1922). 1. Ninety-eight per cent of the people of the United States are within range of at least one of the more than 1400 operating or authorized stations, WnrrE, TiE Atox- CAN RAnio 204 (1947), while approximately four-fifths of the country's homes, it may be estimated, are equipped with radios. SIXTEENTH CENSUS, HousINo, Vol. I1, pt. I, p. 28 (1943). The picture is darkened by the fact that 5,575 of the cities of 1,000 or more population have no local stations and, accordingly, can receive only programs broadcast to extensive areas and not aimed at the needs of particular localities. While frequency modulation (FM) makes technically possible indigenous coverage of these communities, construction expense forces the prediction that most small towns will continue to receive only outside treatment of local news. -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

Hadiotv EXPERIMENTER AUGUST -SEPTEMBER 75C

DXer's DREAM THAT ALMOST WAS SHASILAND HadioTV EXPERIMENTER AUGUST -SEPTEMBER 75c BUILD COLD QuA BREE ... a 2-FET metal moocher to end the gold drain and De Gaulle! PIUS Socket -2 -Me CB Skyhook No -Parts Slave Flash Patrol PA System IC Big Voice www.americanradiohistory.com EICO Makes It Possible Uncompromising engineering-for value does it! You save up to 50% with Eico Kits and Wired Equipment. (%1 eft ale( 7.111 e, si. a er. ortinastereo Engineering excellence, 100% capability, striking esthetics, the industry's only TOTAL PERFORMANCE STEREO at lowest cost. A Silicon Solid -State 70 -Watt Stereo Amplifier for $99.95 kit, $139.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3070. A Solid -State FM Stereo Tuner for $99.95 kit. $139.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3200. A 70 -Watt Solid -State FM Stereo Receiver for $169.95 kit, $259.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3570. The newest excitement in kits. 100% solid-state and professional. Fun to build and use. Expandable, interconnectable. Great as "jiffy" projects and as introductions to electronics. No technical experience needed. Finest parts, pre -drilled etched printed circuit boards, step-by-step instructions. EICOGRAFT.4- Electronic Siren $4.95, Burglar Alarm $6.95, Fire Alarm $6.95, Intercom $3.95, Audio Power Amplifier $4.95, Metronome $3.95, Tremolo $8.95, Light Flasher $3.95, Electronic "Mystifier" $4.95, Photo Cell Nite Lite $4.95, Power Supply $7.95, Code Oscillator $2.50, «6 FM Wireless Mike $9.95, AM Wireless Mike $9.95, Electronic VOX $7.95, FM Radio $9.95, - AM Radio $7.95, Electronic Bongos $7.95. -

The JW.HAU CORK Tw M Tm Lifralji MANY LOCAL RESIDENTS

■ 'V-'- 'i^Si , ---.-afe,- --■■ WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, »AQB f XnJBTSBH AVBBAOB DAILY OIBODLA'nON WBATBBI inattrlirster lEvntino V e n # fa r tha Meffth at AiNSiBL 1887 Bart$»M O peolng The Toung Peofile’s Legion of the Manchester Tent, Knights of the Mias Faith Fallow of Main stieot week win not be outlined until be keeping although there are enough Salvation Army will open Its fall Maccabees wlU have a peach short sailed today on the 8. 8. ’Tlarlnthla" learns the total enrollment. Most applicanta to form classes, while FUr benight and FHday; oeoM- eTlLISH-AMERICAN for a 10-day cruise to Havana and 80 HERE ENROLL 5 , 8 6 1 . s : ABOUTTOWN activlUes with a special meeting cake supper thU evening at 7:18 of those who registered last night sloyd work and cl^senahlp wlU Bleailier-M the Andit tw m tm lifralJi at the citadel tonight In charge of In the Batch and Brown ball. A Nassau, B.I. Her slater, Hlaa Phillis probably be dropped unless a good- DANCES Fallow, accompanied her to New signed up for the classes In advanced Bareas at Otaeolatloas sA - AS namteia of Um Red Men's Batordap Eyeafag Sept. S5tli Captain Fred Ladlow and Lieuten brief business meeting will follow. ly number of registrations for these MANCHESTER — A CITY OF VnXAflE CHARM George M. Bidwell, chairman of the Y ork. typing aad stenography. A slight ttngo eonunIttM and ether mem- Pnlaskt Hall, Korth St. ant Walter Hooper of WiUlmantle. FOR N I ^ SCHOOL falling off was noticed In registra- subjects are received tonight. -

Complete Radio Roster

Station Freq City of License State Phone Website WAAW-FM 94.7 WILLISTON SC 803-649-6405 www.shout947.com WABV-AM 1590 ABBEVILLE SC 864-223-9402 www.radioinspiracion1590.com WOSF-FM 105.3 GAFFNEY SC 704-548-7800 1053rnb.com WAGS-AM 1380 BISHOPVILLE SC 803-484-5415 WAIM-AM 1230 ANDERSON SC 864-226-1511 waim.us WPUB-FM 102.7 CAMDEN SC 803-438-9002 www.kool1027.com WALD-AM 1080 JOHNSONVILLE SC 803-939-9530 WANS-AM 1280 ANDERSON SC 864-844-9009 WARQ-FM 93.5 COLUMBIA SC 803-695-8600 www.q935.com WASC-AM 1530 SPARTANBURG SC 864-585-1530 WKZQ-FM 96.1 FORESTBROOK SC 843-448-1041 www.961wkzq.com WAVO-AM 1150 ROCK HILL SC 704-596-1240 www.1150wavo.com WAZS-AM 980 SUMMERVILLE SC 704-405-3170 WBCU-AM 1460 UNION SC 864-427-2411 www.wbcuradio.com WHGS-AM 1270 HAMPTON SC 803-943-5555 WBHC-FM 92.1 HAMPTON SC 803-943-5555 allhits921.blogspot.com/ WBLR-AM 1430 BATESBURG SC 706-309-9609 www.gnnradio.org WBT-FM 99.3 CHESTER SC 704-374-3500 www.wbt.com WNKT-FM 107.5 EASTOVER SC 803-796-7600 www.1075thegame.com WULR-AM 980 YORK SC 336-434-5025 www.cadenaradialnuevavida.com WCAM-AM 1590 CAMDEN SC 803-438-9002 www.kool1027.com WAHT-AM 1560 CLEMSON SC 864-654-4004 www.wccpfm.com WCCP-FM 105.5 CLEMSON SC 864-654-4004 www.wccpfm.com WCKI-AM 1300 GREER SC 864-877-8458 catholicradioinsc.com WCMG-FM 94.3 LATTA SC 843-661-5000 www.magic943fm.com WCOS-AM 1400 COLUMBIA SC 803-343-1100 foxsportsradio1400.iheart.com WCOS-FM 97.5 COLUMBIA SC 803-343-1100 975wcos.iheart.com WCRE-AM 1420 CHERAW SC 843-537-7887 www.myfm939.com WCRS-AM 1450 GREENWOOD SC 864-941-9277 www.wcrs1450am.net