High Hopes for Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

The Don Lee-Columbia System

THE DON LEE-COLUMBIA SYSTEM: By Mike Adams 111 Sutter Street was not the only network broadcast address during the thirties. The other was 1000 Van Ness Avenue, the Don Lee Cadillac Building, headquarters for KFRC and the Don Lee-Columbia Network. It was there that another radio legend was born. Don Lee was a prominent Los Angeles automobile dealer, who had owned all the Cadillac and LaSalle dealerships in the State of California for over 20 years. After making a substantial fortune in the auto business, he decided to try his hand at broadcasting.1 In 1926, he purchased KFRC in San Francisco from the City of Paris department store. The following year he bought KHJ in Los Angeles and connected the two stations by telephone line to establish the Don Lee Broadcasting System. From the beginning, Lee spared no expense to make these two stations among the finest in the nation, as a 1929 article from Broadcast Weekly attests: Both KHJ and KFRC have large complete staffs of artists, singers and entertainers, with each station having its own Don Lee Symphony Orchestra, dance band and organ, plus all of the musical instruments that can be used successful in broadcasting. It is no idle boast that either KHJ or KFRC could operate continuously without going outside their own staffs for talent, and yet give a variety with an appeal to every type of audience.[2] In 1929, CBS still had no affiliates west of the Rockies, and this was making it difficult for the network to compete with its larger rival, NBC. -

SIRIUS Satellite Radio Hires Dynamic Radio Industry Advertising Executives

SIRIUS Satellite Radio Hires Dynamic Radio Industry Advertising Executives Sam Benrubi, Stephen Smith To Form Cornerstone for Building SIRIUS' Ad Sales Team SIRIUS Committed to Building Ad Revenue on its Sports, Talk, Traffic, News, and Entertainment Channels NEW YORK - February 24, 2005 - SIRIUS Satellite Radio (NASDAQ: SIRI) today announced that it hired two of the radio industry's most respected and accomplished advertising executives, Sam Benrubi and Stephen Smith, to help build advertising revenue on its non-music channels. SIRIUS provides 65 channels of 100% commercial-free music; SIRIUS does offer commercial time to advertisers on its more than 55 talk, traffic, news, sports and entertainment channels. The appointments follow key programming announcements that enhance advertisers' ability to buy time on SIRIUS to reach a national audience. Recent programming announcements include this week's announcement that SIRIUS will be the new home of NASCAR in 2007; SIRIUS will sell all advertising time on its NASCAR channel and during the race broadcasts. "Sam and Steve are two of the best radio advertising sales executives in the country, with deep experience in broadcast advertising sales related to sports, Howard Stern, and other prominent talk show personalities," said Scott Greenstein, SIRIUS President of Entertainment and Sports. "Their appointments are an important part of the next step in the growth of SIRIUS, following our acquisition of significant programming assets that now allow SIRIUS promising advertising revenue possibilities. They will lead a team to build our advertising revenue stream to its fullest." Sam Benrubi, a senior nationwide advertising executive who has led network and local sales teams at Westwood One and Infinity Broadcasting, was named Senior Vice President, Advertising Sales. -

Announced Tacks on Children's Programs" Be Counter- of 1954 Over the Same Period Last Year, It by George Whitney, Acted by Stations on the Local Level

STATIONS Mortenson Leaves Don Lee WRC -WNBW (TV) Note Rise To Manage KFMB San Diego Defends Child Shows In Local, Spot Business ART MORTENSON, national advertising man- SUGGESTION has been made to sta- ager for Don Lee Broadcasting System in Holly- tion clients by Joseph J. Weed, presi- NBC -owned WRC and WNBW (TV) Washing- wood, resigned effective yesterday (Sunday) to dent of Weed Television Corp., station ton have increased business in both local and join KFMB San Diego as manager, it has been representatives, that "loose and general at- national spot advertising for the first six months announced tacks on children's programs" be counter- of 1954 over the same period last year, it by George Whitney, acted by stations on the local level. He was reported last week. general manager of advocated that plans be laid in the sum- WRC's income from local and national spot KFMB - AM - TV. mer months for a fall schedule of local for the first half of 1954 was 13.6% over the Hobby Myers, who talks by an outstanding program per- same period in 1953, with June business 15.4% has resigned as sonality of each station to parent- teacher, higher than the corresponding month last year KFMB manager, scout and church groups in which the -and higher than any June since 1947. will reveal his future standards of program acceptability by WNBW's non -network business rose 31.2% plans after an ex- the station be outlined. Mr. Weed con- for the first six months of 1954 compared with tended vacation, it tended that criticisms generally have been the same period in 1953. -

Glenn Miller 1939 the Year He Found the Sound

GLENN MILLER 1939 THE YEAR HE FOUND THE SOUND Dedicated to the Glenn Miller Birthpace Society June 2019 Prepared by: Dennis M. Spragg Glenn Miller Archives Alton Glenn Miller (1904-1944) From Glenn Miller Declassified © 2017 Dennis M. Spragg Sound Roots Glenn Miller was one of the foremost popular music celebrities of the twentieth century. The creative musician and successful businessman was remarkably intuitive and organized, but far from perfect. His instincts were uncanny, although like any human being, he made mistakes. His record sales, radio popularity, and box-office success at theaters and dance halls across the nation were unsurpassed. He had not come to fame and fortune without struggle and was often judgmental and stubborn. He had remarkable insight into public taste and was not afraid to take risks. To understand Miller is to appreciate his ideals and authenticity, essential characteristics of a prominent man who came from virtually nothing. He sincerely believed he owed something to the nation he loved and the fellow countrymen who bought his records. The third child of Lewis Elmer Miller and Mattie Lou Cavender, Alton Glen Miller was born March 1, 1904, at 601 South 16th Street in Clarinda, a small farming community tucked in the southwest corner of Iowa. Miller’s middle name changed to Glenn several years later in Nebraska. His father was an itinerant carpenter, and his mother taught school. His older brother, Elmer Deane, was a dentist. In 1906 Miller’s father took his family to the harsh sand hills of Tryon, Nebraska, near North Platte. The family moved to Hershey, Nebraska, in the fall of 1912 and returned to North Platte in July 1913, where Glenn’s younger siblings John Herbert and Emma Irene were born. -

Experiments in the Performance of Participation and Democracy

Respublika! Experiments in the performance of participation and democracy edited by Nico Carpentier 1 2 3 Publisher NeMe, Cyprus, 2019 www.neme.org © 2019 NeMe Design by Natalie Demetriou, ndLine. Printed in Cyprus by Lithografica ISBN 978-9963-9695-8-6 Copyright for all texts and images remains with original artists and authors Respublika! A Cypriot community media arts festival was realised with the kind support from: main funder other funders in collaboration with support Further support has been provided by: CUTradio, Hoi Polloi (Simon Bahceli), Home for Cooperation, IKME Sociopolitical Studies Institute, Join2Media, KEY-Innovation in Culture, Education and Youth, Materia (Sotia Nicolaou and Marina Polycarpou), MYCYradio, Old Nicosia Revealed, Studio 21 (Dervish Zeybek), Uppsala Stadsteater, Chystalleni Loizidou, Evi Tselika, Anastasia Demosthenous, Angeliki Gazi, Hack66, Limassol Hacker Space, and Lefkosia Hacker Space. Respublika! Experiments in the performance of participation and democracy edited by Nico Carpentier viii Contents Foreword xv An Introduction to Respublika! Experiments in the Performance of 3 Participation and Democracy Nico Carpentier Part I: Participations 14 Introduction to Participations 17 Nico Carpentier Community Media as Rhizome 19 Nico Carpentier The Art of Community Media Organisations 29 Nico Carpentier Shaking the Airwaves: Participatory Radio Practices 34 Helen Hahmann Life:Moving 42 Briony Campbell and the Life:Moving participants and project team Life:Moving - The Six Participants 47 Briony Campbell -

Broadcasting Emay 4 the News Magazine of the Fifth Estate Vol

The prrime time iinsups fort Vail ABC-TV in Los Angeles LWRT in Washington Broadcasting EMay 4 The News Magazine of the Fifth Estate Vol. 100 No. 18 50th Year 1981 m Katz. The best. The First Yea Of Broadcasting 1959 o PAGE 83 COPYRIGHT 0 1981 IA T COMMUNICATIONS CO Afready sok t RELUON PEOPLE... Abilene-Sweetwater . 65,000 Diary we elt Raleigh-Durham 246,000 Albany, Georgia 81,000 Rapid City 39,000 Albany-Schenectady- Reno 30,000 Troy 232,000 Richmond 206,000 Albuquerque 136,000 Roanoke-Lynchberg 236,000 Alexandria, LA 57,000 Detroit 642,000 Laredo 19,000 Rochester, NY 143,000 Alexandria, MN' 25,000 Dothan 62,000 Las Vegas 45,000 Rochester-Mason City- Alpena 11,000 Dubuque 18,000 Laurel-Hattiesburg 6,000 Austin 75,000 Amarillo 81,000 Duluth-Superior 107,000 Lexington 142,000 Rockford 109,000 Anchorage 27,000 El Centro-Yuma 13,000 Lima 21,000 Roswell 30,000 Anniston 27,000 El Paso 78,000 Lincoln-Hastings- Sacramento-Stockton 235,000 Ardmore-Ada 49,000 Elmira 32,000 Kearney 162,000 St. Joseph 30,000 Atlanta 605,000 Erie 71,000 Little Rock 197,000 St. Louis 409,000 Augusta 88,000 Eugene 34,000 Los Angeles 1 306,000 Salinas-Monterey 59,000 Austin, TX 84,000 Eureka 17,000 Louisville 277,000 Salisbury 30,000 Bakersfield 36,000 Evansville 117,000 Lubbock 78,000 Salt Lake City 188,000 Baltimore 299,000 Fargo 129,000 Macon 109,000 San Angelo 22,000 Bangor 68,000 Farmington 5,000 Madison 98,000 San Antonio 199,000 Baton Rouge 138,000 Flagstaff 11,000 Mankato 30,000 San Diego 252,000 Beaumont-Port Arthur 96,000 Flint-Saginaw-Bay City 201,000 Marquette 44,000 San Francisco 542,000 Bend 8,000 Florence, SC 89,000 McAllen-Brownsville Santa Barbara- (LRGV) 54,000 Billings 47,000 Ft. -

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

Byliner Staff About Humility and Gratitude

Join Us on September 2012 Newsletter of The Press Club of Cleveland From the President Rock Hall Panel Revisits WMMS’s Past and Ed Byers Speculates About Radio’s Future First off, it’s almost By Anastasia Pantsios, Cleveland SCENE Hall of Fame time and People who weren’t around or who were some full disclosure on too young to remember Cleveland in the Stuart Warner’s being ’70s and ’80s might wonder why anyone elected to the Hall of would make a fuss over a mundane “guy- Fame. zone” station like WMMS, with its bland As most of you know, commercial hard rock and its focus on Stuart has chaired The Press Club’s Hall sports and hot babes — appealing to a spe- of Fame committee for as long as I can cific group of males under 30. (L-R) WMMS’s staff; Walt Tiburski, Denny remember, which, in of itself, should In a special program, presented by The Sanders, Gaye Ramstrom, John Gorman, Billy qualify one for induction. But as we all Press Club of Cleveland and the Rock and Bass and moderator Jim Henke, curator, The know, Stuart’s journalism credentials are Roll Hall of Fame, five people who were Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. second to none. pivotal in creating the WMMS legend The instant we found out that Stuart’s spoke at the Rock Hall’s Foster Theatre Sanders, its evening air personality and name had been placed in nomination for about what made the station so dominant behind-the-scenes guide; John Gorman, the Hall, he not only stepped down as in Cleveland and so influential nationwide the hyper-competitive program direc- chairman, but departed the committee — and speculated on whether that influ- tor who took the station to the top of the altogether until after the election. -

Impact Report 2014 Iheartmedia Communities ™ Impact Report 2014 Contents

Impact Report 2014 iHeartMedia Communities ™ Impact Report 2014 Contents Company Overview 02 Executive Letter 04 Community Commitment 06 iHeartMedia 09 2014 Special Projects 12 National Radio Campaigns 30 Radiothons 102 Public Affairs Shows 116 Responding to Disasters 128 Wish Granting 132 Special Events and Fundraising 142 2014 Honorary Awards and Recognition 148 Music Development 160 Local Advisory Boards 174 On-Air Personalities 178 Station Highlights 196 Clear Channel Outdoor 240 Community Commitment 242 Protecting Our Communities 244 National Partners & Programs 248 Market Highlights 258 IMPACT REPORT 2014 | 1 Company Overview ABOUT IHEARTMEDIA, INC. iHeartMedia, Inc. is one of the leading global media and entertainment companies specializing in radio, digital, outdoor, mobile, live events, social and on-demand entertainment and information services for local communities and providing premier opportunities for advertisers. For more company information visit iHeartMedia.com. ABOUT IHEARTMEDIA With 245 million monthly listeners in the U.S., 97 million monthly digital uniques and 196 million monthly consumers of its Total Traffic and Weather Network, iHeartMedia has the largest reach of any radio or television outlet in America. It serves over 150 markets through 858 owned radio stations, and the company’s radio stations and content can be heard on AM/FM, HD digital radio, satellite radio, on the Internet at iHeartRadio.com and on the company’s radio station websites, on the iHeartRadio mobile app, in enhanced auto dashes, on tablets and smartphones, and on gaming consoles. iHeartRadio, iHeartMedia’s digital radio platform, is the No. 1 all-in-one digital audio service with over 500 million downloads; it reached its first 20 million registered users faster than any digital service in Internet history and reached 50 million users faster than any digital music service and even faster than Twitter, Facebook and Pinterest. -

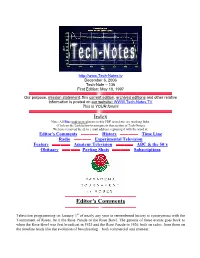

Tech-Note – 136 First Edition: May 18, 1997

http://www.Tech-Notes.tv December 6, 2006 Tech-Note – 136 First Edition: May 18, 1997 Our purpose, mission statement, this current edition, archived editions and other relative information is posted on our website: WWW.Tech-Notes.TV This is YOUR forum! Index Note: All Blue underscored items in this PDF newsletter are working links. (Click on the Link below to navigate to that section of Tech-Notes) We have removed the @ in e-mail address, replacing it with the word at. Editor's Comments History Time Line Radio Experimental Television Feature Amateur Television ABC & the 50’s Obituary Parting Shots Subscriptions Editor's Comments Television programming on January 1st of nearly any year in remembered history is synonymous with the Tournament of Roses, be it the Rose Parade or the Rose Bowl. The genesis of these events goes back to when the Rose Bowl was first broadcast in 1923 and the Rose Parade in 1926, both on radio: from there on the timeline reads like the evolution of broadcasting – both commercial and amateur. It has been a lot of fun and very interesting gathering the information we’ll presenting in this special edition of the Tech-Notes. It is our opinion that if the technical aspects relating to the history of broadcastings involvement isn’t documented somewhere, it will be lost to future generations who may just ask: “How’d they do that?” In this spirit, we contacted the major networks and Los Angeles TV and Radio station, but didn’t really get very far with any of them. -

Cinematheque.Com

PROGRAM SCHEDULE SEP T • OCT 2009 Infoline: 925-3457 100 Arthur St. IN THE EXCHANGE www.winnipegcinematheque.com MONTREAL MAIN (see page 3 for details) Please join the Winnipeg Film Group CinemaCinema LoungeLounge Acclaimed Canadian director John Greyson introduces for the release of our latest publication: Montreal Main, by director Frank Vitale PLACE, a 128 page book Wednesday, 21 October 2009 October 25, 7:00 PM • See page 3 for details featuring 13 essays on 5 – 7 PM > 100 Arthur Street 13 independent feature > Filmmakers and authors in attendance filmmakers from Winnipeg For Sale > winnipegfilmgroup.com DOCUMENTARIES OF THE 21ST CENTURY IN QUEBEC WITH ESSAYS BY October 23 – 25 • See page 4 for details DANISHKA ESTERHAZY ON NORMA BAILEY | SOLOMON NAGLER ON JEFFREY ERBACH | JONAS CHERNICK ON SEAN GARRITY | IOANNIS MOOKAS ON NOAM GONICK | CAELUM VATNSDAL ON GREG HANEC 13 ESSAYS LARISSA FAN ON CLIVE HOLDEN | TRICIA WASNEY ON PAULA KELLY 13 FILMMAKERS Poetic Passages: 1 CITY KENNETH GEORGE GODWIN ON JOHN KOZAK | MIYE BROMBERG ON A PHILIP HOFFMAN RETROSPECTIVE GUY MADDIN | MATTHEW RANKIN ON WINSTON WASHINGTON MOXAM Wednesday Oct. 7, 7:00 & 9:00 PM • See page 5 for details GEOFF PEVERE ON JOHN PAIZS | JONATHAN BALL ON JEFF SOLYLO AND SEAN CARNEY ON CAELUM VATNSDAL The Cinematheque is proud to be in partnership with UMFM Campus Radio...and is a sponsor of Winnipeg’s only film talk radio show Ultrasonic Film. Tune to 101.5 on the FM dial every Thursday evening from 10 PM to 11 PM for the best in film reviews and discussion with hosts James and Lindsay.