Teachers' Guide to the Middle School Public Debate Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

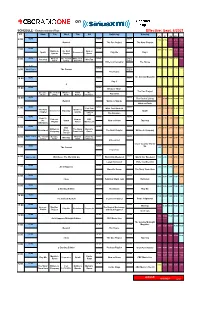

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

DEBATING AGENT of ACTION COUNTERPLANS (I): MORGAN POWERS & EXECUTIVE ORDERS by David M

DEBATING AGENT OF ACTION COUNTERPLANS (I): MORGAN POWERS & EXECUTIVE ORDERS by David M. Cheshier By the end of last year's academic wider than those few discussed here. This Court enforces, then the counterplan to sim- achievement season, agent of action essay does not review the merits of state ply have the Court initiate action which it counterplans were well established as a legislative or judicial action, although those then enforces as it would other decisions generic of choice, and the early indication will obviously be viable strategies in cer- might well be plan inclusive. Or is it? Even if is that they will have a similarly dominant tain debates. It does not review the compli- the outcome is very similar, one might ar- influence in privacy debates. While the cated literatures surrounding the Congres- gue the mandates of the plan are essentially summer experience of students at the sional delegation power, though in some different from the counterplan. And if we Dartmouth Debate Institute may be atypi- debates the delegation/nondelegation issue decide otherwise, wouldn't every cal, almost every round there came down to will arise. Nor does it review the range of counterplan become plan-inclusive, if only an agent counterplan, a Clinton popularity/ potential international action counterplans because both the plan and counterplan political capital position, a privacy critique, available on this topic, most of which would share similar language regarding "normal and associated theory attacks. The strate- presumably involve either consultation or means", "enforcement," and "funding"? gic benefits are plain to see - agent harmonization of American privacy policy Since there is, in certain quarters, a counterplans often capture the case advan- with the European Union - it was only little growing hostility to plan-inclusiveness, and tage and open the way for political process more than a month ago that U.S. -

Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature

PAYING ATTENTION TO PUBLIC READERS OF CANADIAN LITERATURE: POPULAR GENRE SYSTEMS, PUBLICS, AND CANONS by KATHRYN GRAFTON BA, The University of British Columbia, 1992 MPhil, University of Stirling, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2010 © Kathryn Grafton, 2010 ABSTRACT Paying Attention to Public Readers of Canadian Literature examines contemporary moments when Canadian literature has been canonized in the context of popular reading programs. I investigate the canonical agency of public readers who participate in these programs: readers acting in a non-professional capacity who speak and write publicly about their reading experiences. I argue that contemporary popular canons are discursive spaces whose constitution depends upon public readers. My work resists the common critique that these reading programs and their canons produce a mass of readers who read the same work at the same time in the same way. To demonstrate that public readers are canon-makers, I offer a genre approach to contemporary canons that draws upon literary and new rhetorical genre theory. I contend in Chapter One that canons are discursive spaces comprised of public literary texts and public texts about literature, including those produced by readers. I study the intertextual dynamics of canons through Michael Warner’s theory of publics and Anne Freadman’s concept of “uptake.” Canons arise from genre systems that are constituted to respond to exigencies readily recognized by many readers, motivating some to participate. I argue that public readers’ agency lies in the contingent ways they select and interpret a literary work while taking up and instantiating a canonizing genre. -

Learning to Spot Common Fallacies

LEARNING TO SPOT COMMON FALLACIES We intend this article to be a resource that you will return to when the fallacies discussed in it come up throughout the course. Do not feel that you need to read or master the entire article now. We’ve discussed some of the deep-seated psychological obstacles to effective logical and critical thinking in the videos. This article sets out some more common ways in which arguments can go awry. The defects or fallacies presented here tend to be more straightforward than psychological obstacles posed by reasoning heuristics and biases. They should, therefore, be easier to spot and combat. You will see though, that they are very common: keep an eye out for them in your local paper, online, or in arguments or discussions with friends or colleagues. One reason they’re common is that they can be quite effective! But if we offer or are convinced by a fallacious argument we will not be acting as good logical and critical thinkers. Species of Fallacious Arguments The common fallacies are usefully divided into three categories: Fallacies of Relevance, Fallacies of Unacceptable Premises, and Formal Fallacies. Fallacies of Relevance Fallacies of relevance offer reasons to believe a claim or conclusion that, on examination, turn out to not in fact to be reasons to do any such thing. 1. The ‘Who are you to talk?’, or ‘You Too’, or Tu Quoque Fallacy1 Description: Rejecting an argument because the person advancing it fails to practice what he or she preaches. Example: Doctor: You should quit smoking. It’s a serious health risk. -

Debate Association & Debate Speech National ©

© National SpeechDebate & Association DEBATE 101 Everything You Need to Know About Policy Debate: You Learned Here Bill Smelko & Will Smelko DEBATE 101 Everything You Need to Know About Policy Debate: You Learned Here Bill Smelko & Will Smelko © NATIONAL SPEECH & DEBATE ASSOCIATION DEBATE 101: Everything You Need to Know About Policy Debate: You Learned Here Copyright © 2013 by the National Speech & Debate Association All rights reserved. Published by National Speech & Debate Association 125 Watson Street, PO Box 38, Ripon, WI 54971-0038 USA Phone: (920) 748-6206 Fax: (920) 748-9478 [email protected] No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, now known or hereafter invented, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, information storage and retrieval, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. The National Speech & Debate Association does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, age, gender identity, gender expression, affectional or sexual orientation, or disability in any of its policies, programs, and services. Printed and bound in the United States of America Contents Chapter 1: Debate Tournaments . .1 . Chapter 2: The Rudiments of Rhetoric . 5. Chapter 3: The Debate Process . .11 . Chapter 4: Debating, Negative Options and Approaches, or, THE BIG 6 . .13 . Chapter 5: Step By Step, Or, It’s My Turn & What Do I Do Now? . .41 . Chapter 6: Ten Helpful Little Hints . 63. Chapter 7: Public Speaking Made Easy . -

The Fallacy of Composition and Meta-Argumentation"

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 10 May 22nd, 9:00 AM - May 25th, 5:00 PM Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro's "The fallacy of composition and meta-argumentation" Michel Dufour Sorbonne-Nouvelle, Institut de la Communication et des Médias Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Dufour, Michel, "Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro's "The fallacy of composition and meta- argumentation"" (2013). OSSA Conference Archive. 49. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA10/papersandcommentaries/49 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro’s “The fallacy of composition and meta-argumentation” MICHEL DUFOUR Department «Institut de la Communication et des Médias» Sorbonne-Nouvelle 13 rue Santeuil 75231 Paris Cedex 05 France [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION In his paper on the fallacy of composition, Maurice Finocchiaro puts forward several important theses about this fallacy. He also uses it to illustrate his view that fallacies should be studied in light of the notion of meta-argumentation at the core of his recent book (Finocchiaro, 2013). First, he expresses his puzzlement. Some authors have claimed that this fallacy is quite common (this is the ubiquity thesis) but it seems to have been neglected by scholars. -

Fallacies in Reasoning

FALLACIES IN REASONING FALLACIES IN REASONING OR WHAT SHOULD I AVOID? The strength of your arguments is determined by the use of reliable evidence, sound reasoning and adaptation to the audience. In the process of argumentation, mistakes sometimes occur. Some are deliberate in order to deceive the audience. That brings us to fallacies. I. Definition: errors in reasoning, appeal, or language use that renders a conclusion invalid. II. Fallacies In Reasoning: A. Hasty Generalization-jumping to conclusions based on too few instances or on atypical instances of particular phenomena. This happens by trying to squeeze too much from an argument than is actually warranted. B. Transfer- extend reasoning beyond what is logically possible. There are three different types of transfer: 1.) Fallacy of composition- occur when a claim asserts that what is true of a part is true of the whole. 2.) Fallacy of division- error from arguing that what is true of the whole will be true of the parts. 3.) Fallacy of refutation- also known as the Straw Man. It occurs when an arguer attempts to direct attention to the successful refutation of an argument that was never raised or to restate a strong argument in a way that makes it appear weaker. Called a Straw Man because it focuses on an issue that is easy to overturn. A form of deception. C. Irrelevant Arguments- (Non Sequiturs) an argument that is irrelevant to the issue or in which the claim does not follow from the proof offered. It does not follow. D. Circular Reasoning- (Begging the Question) supports claims with reasons identical to the claims themselves. -

Is the Consultant Counterplan Legitimate

THE D G E IS THE CONSULTATION COUNTERPLAN LEGITIMATE? by David M. Cheshier The most popular category of counterplan on the “weap- ons of mass destruction” (WMD) topic involves consultation. The negative argues that instead of promptly adopting and imple- menting the plan, the United States should consult some speci- fied government beforehand, only moving forward if the plan meets the approval of our consultation partner. Many versions were produced over the summer, including counterplans to consult NATO, Japan, Russia, China, Israel, India, and Canada. On this resolution, the consultation counterplan is often an irresistible strategic option for the negative. Because most plan texts as written advocate immediate implementation (if they don’t the affirmative may be in topicality trouble), the counterplan is mutually exclusive, for one can’t act and consult about acting at the same time. Because the resolution locks the affirmative into frequently defending policies the rest of the world would agree to, the counterplan consultation process would usually culminate in the eventual passage of the plan. Thus, the negative is able to argue there is little or no downside to asking for input. Consulta- tion promises to capture the advantages, with the value added benefit of an improvement in America’s relations with NATO, Rus- sia, or China (from here on I’ll use Russia as my example). The view is also prevalent that the consultation counterplan cannot be permuted by the affirmative, since to do so invariably commits the affirmative either to severance or intrinsicness (more on this shortly). Consultation is here to stay. For the counterplan to work, the negative must include lan- guage, which gives the consultation partner a “veto” over the plan. -

334 CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES a Deductive Fallacy Is

CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES A deductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument necessarily follows from the truth of the premises given, when in fact that conclusion does not necessarily follow from those premises. An inductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument is made more probable by its relationship with the premises of the argument, when in fact it is not. We will cover two kinds of fallacies: formal fallacies and informal fallacies. An argument commits a formal fallacy if it has an invalid argument form. An argument commits an informal fallacy when it has a valid argument form but derives from unacceptable premises. A. Fallacies with Invalid Argument Forms Consider the following arguments: (1) All Europeans are racist because most Europeans believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans and all people who believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans are racist. (2) Since no dogs are cats and no cats are rats, it follows that no dogs are rats. (3) If today is Thursday, then I'm a monkey's uncle. But, today is not Thursday. Therefore, I'm not a monkey's uncle. (4) Some rich people are not elitist because some elitists are not rich. 334 These arguments have the following argument forms: (1) Some X are Y All Y are Z All X are Z. (2) No X are Y No Y are Z No X are Z (3) If P then Q not-P not-Q (4) Some E are not R Some R are not E Each of these argument forms is deductively invalid, and any actual argument with such a form would be fallacious. -

Quantifying Aristotle's Fallacies

mathematics Article Quantifying Aristotle’s Fallacies Evangelos Athanassopoulos 1,* and Michael Gr. Voskoglou 2 1 Independent Researcher, Giannakopoulou 39, 27300 Gastouni, Greece 2 Department of Applied Mathematics, Graduate Technological Educational Institute of Western Greece, 22334 Patras, Greece; [email protected] or [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 July 2020; Accepted: 18 August 2020; Published: 21 August 2020 Abstract: Fallacies are logically false statements which are often considered to be true. In the “Sophistical Refutations”, the last of his six works on Logic, Aristotle identified the first thirteen of today’s many known fallacies and divided them into linguistic and non-linguistic ones. A serious problem with fallacies is that, due to their bivalent texture, they can under certain conditions disorient the nonexpert. It is, therefore, very useful to quantify each fallacy by determining the “gravity” of its consequences. This is the target of the present work, where for historical and practical reasons—the fallacies are too many to deal with all of them—our attention is restricted to Aristotle’s fallacies only. However, the tools (Probability, Statistics and Fuzzy Logic) and the methods that we use for quantifying Aristotle’s fallacies could be also used for quantifying any other fallacy, which gives the required generality to our study. Keywords: logical fallacies; Aristotle’s fallacies; probability; statistical literacy; critical thinking; fuzzy logic (FL) 1. Introduction Fallacies are logically false statements that are often considered to be true. The first fallacies appeared in the literature simultaneously with the generation of Aristotle’s bivalent Logic. In the “Sophistical Refutations” (Sophistici Elenchi), the last chapter of the collection of his six works on logic—which was named by his followers, the Peripatetics, as “Organon” (Instrument)—the great ancient Greek philosopher identified thirteen fallacies and divided them in two categories, the linguistic and non-linguistic fallacies [1]. -

Ccofse Policy Debate Glossary Advantage: a Description Used By

CCofSE Policy Debate Glossary advantage: a description used by the affirmative to explain what beneficial effects will result from its plan. affirmative: The team in a debate which supports the resolution and speaks first and last in the order of the speeches. affirmative case: The initial affirmative position (presented in the Affirmative Constructive) which demonstrates that there is a need for change because there is a serious problem (harm, or need) which the present system cannot solve (inherency) but which can be solved by the affirmative plan (solvency). affirmative plan: The policy action advocated by the affirmative burden of proof: 1) The requirement that sufficient evidence or reasoning to prove a claim should be presented; 2) the requirement that the affirmative must prove the stock issues. burden of rebuttal or clash: The requirement that each speaker continue the debate by calling into question or disputing the opposition's argument on the substantive issues. comparative advantage case: An affirmative case format that argues desirable benefits of the plan in contrast to the present system. It claims advantages in comparison to present policies. constructives: The first four speeches of the debate, the two Affirmative Constructives (1AC, 2AC) and the two Negative Constructives (1NC, 2NC). Arguments are initiated in these speeches and extended in rebuttals. criteria case: An affirmative case format that posits a goal and then outlines the criteria necessary to achieve the goal. cross-examination: a three minute period following each of the constructive speeches in which a member of the opposing team directly questions the speaker. disadvantage (“DA” or "disad"): An undesirable, effect of the plan. -

A Student's Guide to Classic Debate Competition

Learning Classic Debate A Student’s Guide to Classic Debate Competition By Todd Hering © 2000 Revised 2007 Learning Classic Debate 2 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: Understanding the Classic Debate Format Chapter 3: Argumentation & Organization Chapter 4: Delivery Chapter 5: Research & Evidence Chapter 6: Writing Your Case Chapter 7: The Rules of Classic Debate To The Reader: Welcome to “Learning Classic Debate.” This guide is intended to help you prepare for Classic Debate competition. The Classic Debate League was launched in the fall of 2000. The classic format is intended to produce straightforward debates that reward competitors for their preparation, argumentation, and delivery skills. If you find topics in this guide to be confusing, please e-mail the author at the address below so that you can get an answer to your question and so that future editions may be improved. Thanks and good luck with your debates. About the author: Todd Hering debated for Stillwater High School from 1989-1991. After graduating, he served as an assistant coach at Stillwater from 1991-1994. In 1994, Hering became head debate coach at Stillwater, a position he held until 1997 when he moved to the new Eastview High School in Apple Valley, MN. Hering is currently a teacher and head debate coach at Eastview and is the League Coordinator for the Classic Debate League. Contact Information: Todd Hering Eastview High School 6200 140th Street West Apple Valley, MN 55124-6912 Phone: (651) 683-6969 ext. 8689 E-Mail: [email protected] Learning Classic Debate 3 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Competitive interscholastic debates have occurred in high schools for well over a century.