Conference Proceedings Financial Reform and the Real Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Annual Report

2011 / 2012 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Director’s Message………………………………………………….…..3 Mission and SCEPA Team………..………………………..….….….4 Research Assistants………………………………………………….....5 Research Projects………………………………..……………………...6 Research Papers….……………………………………………………....9 Public Events………………………………………………………….…..14 2 DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE At SCEPA, we are committed to supporting research projects that advance positive change. Our formula is simple. We start with high‐quality, peer‐reviewed academic research, prescribe innovative solutions for the nation’s economic questions, and end with high‐impact outreach strategies that inform and educate policy makers, opinion leaders, advocates and the public. This fiscal year, we made strategic investments in our ability to facilitate this theory of change. Namely, we focused on building a solid platform to support research, including building our communications capacity and increasing our collaboration with coalition partners. In 2010, we went live with a new website, www.economicpolicyresearch.org, to replace our previous static site for one which gave us the functionality of a modern communications platform. Now, we have the functionality to allow our research team and collaborators an interactive forum to discuss public events, post research, and respond to Teresa Ghilarducci, SCEPA questions within the larger issue environment. Supportive communications and social media, including our Director and Professor, @SCEPA_Economics Twitter feed and Facebook page, allow us to target our many interactive audiences and build a Bernard L. and Irene Schwartz Chair in Economic rapid response capability for both traditional and non‐traditional media. Policy Analysis In the first year, SCEPA’s website climbed to second on Google for economic policy research, putting our site in the company of older, more resourced organizations. -

Speech by Andy Haldane at the Bank of Estonia, Tallinn, on Wednesday

Folk Wisdom Speech given by Andrew G Haldane Chief Economist Bank of England 100th Anniversary of the Bank of Estonia Tallinn, Estonia 19 September 2018 The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Bank of England or the Monetary Policy Committee. I would like to thank Shiv Chowla, John Lewis, Jack Meaning and Sophie Stone for their help in preparing the text and to Nicholas Gruen and Matthew Taylor for discussions on these issues. I would like to thank David Bholat, Ben Broadbent, Janine Collier, Laura Daniels, Jonathan Fullwood, Andrew Hebden, Paul Lowe, Clare Macallan and Becky Maule and for their comments and contributions. 1 All speeches are available online at www.bankofengland.co.uk/speeches I am delighted to be here to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Bank of Estonia. It is a particular privilege to be giving this lecture in the Bank’s “Independence Hall” – the very spot where, on 24 February 1918, Estonia’s Provisional Government was formed. The founding of the Bank of Estonia followed on the Republic’s first birthday in 1919. Reaching your first century is a true milestone for any person or institution. In the UK, when you reach your 100th birthday you receive a signed card of congratulations from the Queen. I am afraid I have no royal birthday card for you today. But I have the next best thing – another speech from another central banker. Times are tough in central banking. Central banks have borne much of the burden of supporting the global economy as it has recovered from the global financial crisis. -

Roper Center Archives Update September, 2006

Roper Center Archives Update September, 2006 Where thinking people go to learn what people are thinking. Roper Center Archives Update September, 2006 Highlights: ¾ Pew Research Center Poll: The Right to Die, II interviews where conducted November 9-27, 2005 by Princeton Survey Research Associates International. ¾ Los Angeles Times California Primary Election Exit Poll on June 6, 2006. ¾ Pew Research Center’s January and February 2006 News Interest Index. ¾ 4 new SRBI/Time Magazine Polls conducted from June to August 2006. Roper Center Archives Update September, 2006 New Studies United States -- National adult samples Study Title: Hart-McInturff/NBC/WSJ Poll # 2005-6053: Politics/News Stories/Schiavo Case/Tax Cuts/Social Security/Iraq/The Pope/Immigration/Steroids Study #: USNBCWSJ2005-6053 Methodology: Survey by: NBC News and The Wall Street Journal Conducted by Hart and McInturff Research Companies, March 31-April 3, 2005, and based on telephone interviews with a National adult sample of 1,002. Variables: 104 Topical Coverage: Direction of the country (1); George W. Bush job performance (3); Congress job performance (1); ranking feelings about public figures (6); Republican Party job performance (1); ; roles Democrats in Congress should play (1); filibuster for judicial nominations (2); federal government role in morals and values (1); congressional action on certain issues (11); subjects in the news (11); Terri Schiavo (8); tax cuts (1); Social Security (9); Social Security vs. Medicare (1); war in Iraq (3); influence of Pope and Catholic Church (4); immigration (4); military threats to the United States (8); baseball fan (1); baseball players using steroids (2); stocks vs. real estate investments (1). -

Introduction to Network Science & Visualisation

IFC – Bank Indonesia International Workshop and Seminar on “Big Data for Central Bank Policies / Building Pathways for Policy Making with Big Data” Bali, Indonesia, 23-26 July 2018 Introduction to network science & visualisation1 Kimmo Soramäki, Financial Network Analytics 1 This presentation was prepared for the meeting. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the BIS, the IFC or the central banks and other institutions represented at the meeting. FNA FNA Introduction to Network Science & Visualization I Dr. Kimmo Soramäki Founder & CEO, FNA www.fna.fi Agenda Network Science ● Introduction ● Key concepts Exposure Networks ● OTC Derivatives ● CCP Interconnectedness Correlation Networks ● Housing Bubble and Crisis ● US Presidential Election Network Science and Graphs Analytics Is already powering the best known AI applications Knowledge Social Product Economic Knowledge Payment Graph Graph Graph Graph Graph Graph Network Science and Graphs Analytics “Goldman Sachs takes a DIY approach to graph analytics” For enhanced compliance and fraud detection (www.TechTarget.com, Mar 2015). “PayPal relies on graph techniques to perform sophisticated fraud detection” Saving them more than $700 million and enabling them to perform predictive fraud analysis, according to the IDC (www.globalbankingandfinance.com, Jan 2016) "Network diagnostics .. may displace atomised metrics such as VaR” Regulators are increasing using network science for financial stability analysis. (Andy Haldane, Bank of England Executive -

From Asian to Global Financial Crisis

This page intentionally left blank FROM ASIAN TO GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS This is a unique insider account of the new world of unfettered finance. The author, an Asian regulator, examines how old mindsets, market fundamental- ism, loose monetary policy, carry trade, lax supervision, greed, cronyism, and financial engineering caused both the Asian crisis of the late 1990s and the cur- rent global crisis of 2007–2009. This book shows how the Japanese zero inter- est rate policy to fight deflation helped create the carry trade that generated bubbles in Asia whose effects brought Asian economies down. The study’s main purpose is to demonstrate that global finance is so interlinked and interactive that our current tools and institutional structure to deal with critical episodes are completely outdated. The book explains how current financial policies and regulation failed to deal with a global bubble and makes recommendations on what must change. Andrew Sheng is currently the Chief Adviser to the China Banking Regulatory Commission and a Board Member of the Qatar Financial Centre Regulatory Authority, Khazanah Nasional Berhad and Sime Darby Berhad, Malaysia. He is also Adjunct Professor at the Graduate School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University, Beijing, and at the Faculty of Economics and Administration at the University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur. Mr Sheng was Chairman of the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong from 1998 to 2005. A former central banker with Bank Negara Malaysia and Hong Kong Monetary Authority, between 2003 and 2005 he was Chairman of the Technical Committee of IOSCO, the International Organization of Securities Commissions, the standard setter for securities regulation. -

Who We Are and What We Do

Who We Are and What We Do The Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) is an independent statutory body established by the Securities and Futures Commission Ordinance (SFCO). The SFCO and nine other securities and futures related ordinances were consolidated into the Securities and Futures Ordinance (SFO), which came into operation on 1 April 2003. We are responsible for administering the laws governing the securities and futures markets in Hong Kong and facilitating and encouraging the development of these markets. Our statutory regulatory objectives as set out in the SFO are: >> to maintain and promote the fairness, >> to minimise crime and misconduct in the efficiency, competitiveness, securities and futures industry; transparency and orderliness of the >> to reduce systemic risks in the securities securities and futures industry; and futures industry; and >> to promote understanding by the >> to assist the Financial Secretary in public of the operation and maintaining the financial stability of functioning of the securities and Hong Kong by taking appropriate steps in futures industry; relation to the securities and futures >> to provide protection for members of industry. the public investing in or holding financial products; In carrying out our mission, we aim to ensure Hong Kong’s continued success and development as an international financial centre. The SFC is divided into four operational divisions: Corporate Finance, Intermediaries and Investment Products, Enforcement, and Supervision of Markets. The Commission is supported by -

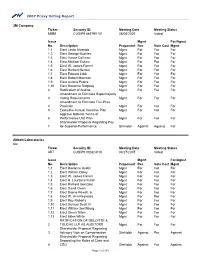

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

Andrew Haldane: the Creative Economy

The Creative Economy Speech given by Andrew G Haldane Chief Economist Bank of England The Inaugural Glasgow School of Art Creative Engagement Lecture The Glasgow School of Art 22 November 2018 The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the Bank of England or the Monetary Policy Committee. I would like to thank Marilena Angeli and Shiv Chowla for their help in preparing the text. I would like to thank Philip Bond, Clare Macallan and Mette Nielson for their comments and contributions. 1 All speeches are available online at www.bankofengland.co.uk/speeches It is a great pleasure to be at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA). For over 170 years, the GSA has been one of the leading educational institutions in the creative arts in Europe. Today, the School continues to provide a conveyor belt of talent that is fuelling the rise in the creative industries, a sector growing rapidly and one where the UK can genuinely be said to be a world-leader. It is creativity, and its role in improving incomes in the economy and well-being in society, that I will discuss this evening. Now, there is a certain irony in me (a middle-aged career public servant) giving a lecture to you (staff and students at one of Europe’s creative hot-spots) about the determinants and benefits of creativity. Don’t worry, that irony is not lost on me. Nonetheless, I hope that by analysing creativity through an economic and historical lens we can learn something about its key ingredients. Developing those raw ingredients, and mixing them appropriately, has been crucial for social and economic progress over the course of history. -

Report of Investigation

REPORT OF INVESTIGATION UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL Investigation into Allegations of Improper Preferential Treatment and Special Access in Connection with the Division of Enforcement's Investigation of Citigroup, Inc. Case No. OIG-559 September 27,2011 This document is subjed to the provisions of th e Privacy Act of 1974, and may require redadion before disdosure to third parties. No redaction has betn performed by the Office of Inspedor Gmeral. Recipients of this report should not disseminate or copy it without the Inspector General's approval. " Report of Investigation Cas. No. OIG-559 Investigation into Allegations of Improper Preferential Treatment and Speeial Access in Connection with the Division of Enforcement's Investigation ofCitigroup, Inc. Table of Contents Introduction and Summary of Results ofthe Investigation ......................................... ..... .. I Scope of the Investigation................................................................................................... 2 Relevant Statutes, Regulations and Pol icies ....................................................................... 4 Results of the Investigation................................................. .. .............................................. 5 I. The Enforcement Staff Investigated Citigroup and Considered Various Charges and Settlement Options ........................................................................................... 5 A. The Enforcement Staff Opened an Investigation -

The Tempered Ordered Probit (TOP) Model with an Application to Monetary Policy William H.Greene Max Gillman Mark N.Harris Christopher Spencer WP 2013 – 10

ISSN 1750-4171 ECONOMICS DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES The Tempered Ordered Probit (TOP) Model With An Application To Monetary Policy William H.Greene Max Gillman Mark N.Harris Christopher Spencer WP 2013 – 10 School of Business and Economics Loughborough University Loughborough LE11 3TU United Kingdom Tel: + 44 (0) 1509 222701 Fax: + 44 (0) 1509 223910 http://www.lboro.ac.uk/departments/sbe/economics/ The Tempered Ordered Probit (TOP) model with an application to monetary policy William H. Greeney Max Gillmanz Mark N. Harrisx Christopher Spencer{ September 2013 Abstract We propose a Tempered Ordered Probit (TOP) model. Our contribution lies not only in explicitly accounting for an excessive number of observations in a given choice category - as is the case in the standard literature on in‡ated models; rather, we introduce a new econometric model which nests the recently developed Middle In‡ated Ordered Probit (MIOP) models of Bagozzi and Mukherjee (2012) and Brooks, Harris, and Spencer (2012) as a special case, and further, can be used as a speci…cation test of the MIOP, where the implicit test is described as being one of symmetry versus asymmetry. In our application, which exploits a panel data-set containing the votes of Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) members, we show that the TOP model a¤ords the econometrician considerable ‡exibility with respect to modelling the impact of di¤erent forms of uncertainty on interest rate decisions. Our …ndings, we argue, reveal MPC members’ asymmetric attitudes towards uncertainty and the changeability of interest rates. Keywords: Monetary policy committee, voting, discrete data, uncertainty, tempered equations. -

Learning to Spot Common Fallacies

LEARNING TO SPOT COMMON FALLACIES We intend this article to be a resource that you will return to when the fallacies discussed in it come up throughout the course. Do not feel that you need to read or master the entire article now. We’ve discussed some of the deep-seated psychological obstacles to effective logical and critical thinking in the videos. This article sets out some more common ways in which arguments can go awry. The defects or fallacies presented here tend to be more straightforward than psychological obstacles posed by reasoning heuristics and biases. They should, therefore, be easier to spot and combat. You will see though, that they are very common: keep an eye out for them in your local paper, online, or in arguments or discussions with friends or colleagues. One reason they’re common is that they can be quite effective! But if we offer or are convinced by a fallacious argument we will not be acting as good logical and critical thinkers. Species of Fallacious Arguments The common fallacies are usefully divided into three categories: Fallacies of Relevance, Fallacies of Unacceptable Premises, and Formal Fallacies. Fallacies of Relevance Fallacies of relevance offer reasons to believe a claim or conclusion that, on examination, turn out to not in fact to be reasons to do any such thing. 1. The ‘Who are you to talk?’, or ‘You Too’, or Tu Quoque Fallacy1 Description: Rejecting an argument because the person advancing it fails to practice what he or she preaches. Example: Doctor: You should quit smoking. It’s a serious health risk. -

Mankiw Coursebook

e Forward Guidance Forward Guidance Forward guidance is the practice of communicating the future path of monetary Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars policy instruments. Such guidance, it is argued, will help sustain the gradual recovery that now seems to be taking place while central banks unwind their massive and Market Participants balance sheets. This eBook brings together a collection of contributions from central Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars and Market Participants bank officials, researchers at universities and central banks, and financial market practitioners. The contributions aim to discuss what economic theory says about Edited by Wouter den Haan forward guidance and to clarify what central banks hope to achieve with it. With contributions from: Peter Praet, Spencer Dale and James Talbot, John C. Williams, Sayuri Shirai, David Miles, Tilman Bletzinger and Volker Wieland, Jeffrey R Campbell, Marco Del Negro, Marc Giannoni and Christina Patterson, Francesco Bianchi and Leonardo Melosi, Richard Barwell and Jagjit S. Chadha, Hans Gersbach and Volker Hahn, David Cobham, Charles Goodhart, Paul Sheard, Kazuo Ueda. CEPR 77 Bastwick Street, London EC1V 3PZ Tel: +44 (0)20 7183 8801 A VoxEU.org eBook Email: [email protected] www.cepr.org Forward Guidance Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars and Market Participants A VoxEU.org eBook Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Centre for Economic Policy Research 3rd Floor 77 Bastwick Street London, EC1V 3PZ UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7183 8801 Email: [email protected] Web: www.cepr.org © 2013 Centre for Economic Policy Research Forward Guidance Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars and Market Participants A VoxEU.org eBook Edited by Wouter den Haan a Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) The Centre for Economic Policy Research is a network of over 800 Research Fellows and Affiliates, based primarily in European Universities.