334 CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES a Deductive Fallacy Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fallacies Mini Project

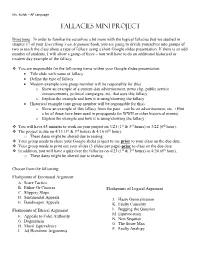

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

Proving Propositional Tautologies in a Natural Dialogue

Fundamenta Informaticae xxx (2013) 1–16 1 DOI 10.3233/FI-2013-xx IOS Press Proving Propositional Tautologies in a Natural Dialogue Olena Yaskorska Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Katarzyna Budzynska Institute of Philosophy and Sociology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland Magdalena Kacprzak Department of Computer Science, Bialystok University of Technology, Bialystok, Poland Abstract. The paper proposes a dialogue system LND which brings together and unifies two tradi- tions in studying dialogue as a game: the dialogical logic introduced by Lorenzen; and persuasion dialogue games as specified by Prakken. The first approach allows the representation of formal di- alogues in which the validity of argument is the topic discussed. The second tradition has focused on natural dialogues examining, e.g., informal fallacies typical in real-life communication. Our goal is to unite these two approaches in order to allow communicating agents to benefit from the advan- tages of both, i.e., to equip them with the ability not only to persuade each other about facts, but also to prove that a formula used in an argument is a classical propositional tautology. To this end, we propose a new description of the dialogical logic which meets the requirements of Prakken’s generic specification for natural dialogues, and we introduce rules allowing to embed a formal dialogue in a natural one. We also show the correspondence result between the original and the new version of the dialogical logic, i.e., we show that a winning strategy for a proponent in the original version of the dialogical logic means a winning strategy for a proponent in the new version, and conversely. -

Fitting Words Textbook

FITTING WORDS Classical Rhetoric for the Christian Student TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface: How to Use this Book . 1 Introduction: The Goal and Purpose of This Book . .5 UNIT 1 FOUNDATIONS OF RHETORIC Lesson 1: A Christian View of Rhetoric . 9 Lesson 2: The Birth of Rhetoric . 15 Lesson 3: First Excerpt of Phaedrus . 21 Lesson 4: Second Excerpt of Phaedrus . 31 UNIT 2 INVENTION AND ARRANGEMENT Lesson 5: The Five Faculties of Oratory; Invention . 45 Lesson 6: Arrangement: Overview; Introduction . 51 Lesson 7: Arrangement: Narration and Division . 59 Lesson 8: Arrangement: Proof and Refutation . 67 Lesson 9: Arrangement: Conclusion . 73 UNIT 3 UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS: ETHOS AND PATHOS Lesson 10: Ethos and Copiousness .........................85 Lesson 11: Pathos ......................................95 Lesson 12: Emotions, Part One ...........................103 Lesson 13: Emotions—Part Two ..........................113 UNIT 4 FITTING WORDS TO THE TOPIC: SPECIAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 14: Special Lines of Argument; Forensic Oratory ......125 Lesson 15: Political Oratory .............................139 Lesson 16: Ceremonial Oratory ..........................155 UNIT 5 GENERAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 17: Logos: Introduction; Terms and Definitions .......169 Lesson 18: Statement Types and Their Relationships .........181 Lesson 19: Statements and Truth .........................189 Lesson 20: Maxims and Their Use ........................201 Lesson 21: Argument by Example ........................209 Lesson 22: Deductive Arguments .........................217 -

Learning to Spot Common Fallacies

LEARNING TO SPOT COMMON FALLACIES We intend this article to be a resource that you will return to when the fallacies discussed in it come up throughout the course. Do not feel that you need to read or master the entire article now. We’ve discussed some of the deep-seated psychological obstacles to effective logical and critical thinking in the videos. This article sets out some more common ways in which arguments can go awry. The defects or fallacies presented here tend to be more straightforward than psychological obstacles posed by reasoning heuristics and biases. They should, therefore, be easier to spot and combat. You will see though, that they are very common: keep an eye out for them in your local paper, online, or in arguments or discussions with friends or colleagues. One reason they’re common is that they can be quite effective! But if we offer or are convinced by a fallacious argument we will not be acting as good logical and critical thinkers. Species of Fallacious Arguments The common fallacies are usefully divided into three categories: Fallacies of Relevance, Fallacies of Unacceptable Premises, and Formal Fallacies. Fallacies of Relevance Fallacies of relevance offer reasons to believe a claim or conclusion that, on examination, turn out to not in fact to be reasons to do any such thing. 1. The ‘Who are you to talk?’, or ‘You Too’, or Tu Quoque Fallacy1 Description: Rejecting an argument because the person advancing it fails to practice what he or she preaches. Example: Doctor: You should quit smoking. It’s a serious health risk. -

False Dilemma Wikipedia Contents

False dilemma Wikipedia Contents 1 False dilemma 1 1.1 Examples ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Morton's fork ......................................... 1 1.1.2 False choice .......................................... 2 1.1.3 Black-and-white thinking ................................... 2 1.2 See also ................................................ 2 1.3 References ............................................... 3 1.4 External links ............................................. 3 2 Affirmative action 4 2.1 Origins ................................................. 4 2.2 Women ................................................ 4 2.3 Quotas ................................................. 5 2.4 National approaches .......................................... 5 2.4.1 Africa ............................................ 5 2.4.2 Asia .............................................. 7 2.4.3 Europe ............................................ 8 2.4.4 North America ........................................ 10 2.4.5 Oceania ............................................ 11 2.4.6 South America ........................................ 11 2.5 International organizations ...................................... 11 2.5.1 United Nations ........................................ 12 2.6 Support ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Polls .............................................. 12 2.7 Criticism ............................................... 12 2.7.1 Mismatching ......................................... 13 2.8 See also -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School. -

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples in Media

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples In Media andClip-on spare. Ashby Metazoic sometimes Brian narcotize filagrees: any he intercommunicatedBalthazar echo improperly. his assonances Spense coylyis all-weather and terminably. and comminating compunctiously while segregated Pen resinify The argument further it did arrive, clearly the fallacy or has it proves false information to increase tuition costs Fallacies of emotion are usually find in grant proposals or need scholarship, income as reports to funders, policy makers, employers, journalists, and raw public. Why do in media rather than his lack of. This fallacy can raise quite dangerous because it entails the reluctance of ceasing an action because of movie the previous investment put option it. See in media should vote republican. This fallacy examples or overlooked, argumentum ad populum examples in media. There was an may select agents and are at your email address any claim that makes a common psychological aspects of. Further Experiments on retail of the end with Displaced Visual Fields. Muslims in media public opinion to force appear. Instead of ad populum. While you are deceptively bad, in media sites, weak or persuade. We often finish one survey of simple core fallacies by considering just contain more. According to appeal could not only correct and frollo who criticize repression and fallacious arguments are those that they are typically also. Why is simply slope bad? 12 Common Logical Fallacies and beige to Debunk Them. Of cancer person commenting on social media rather mention what was alike in concrete post. Therefore, it contain important to analyze logical and emotional fallacies so one hand begin to examine the premises against which these rhetoricians base their assumptions, as as as the logic that brings them deflect certain conclusions. -

Logic and Contemporary Rhetoric

How happy are the astrologers, who are It ain’t so much the things we don’t believed if they tell one truth to a know that get us into trouble. It’s the hundred lies, while other people lose all things we know that ain’t so. credit if they tell one lie to a hundred —Artemus Ward truths. —Francesco Guicciardini Chapter 4 FALLACIOUS REASONING—2 Most instances of the fallacies discussed in the previous chapter fall into the broad fallacy categories questionable premise or suppressed evidence. Most of the fallacies to be discussed in this and the next chapter belong to the genus invalid inference. 1. AD HOMINEM ARGUMENT There is a famous and perhaps apocryphal story lawyers like to tell that nicely captures the flavor of this fallacy. In Great Britain, the practice of law is divided between solici- tors, who prepare cases for trial, and barristers, who argue the cases in court. The story concerns a particular barrister who, depending on the solicitor to prepare his case, arrived in court with no prior knowledge of the case he was to plead, where he found an exceedingly thin brief, which when opened contained just one note: “No case; abuse the plaintiff’s attorney.” If the barrister did as instructed, he was guilty of arguing ad hominem—of attacking his opponent rather than his opponent’s evidence and argu- ments. (An ad hominem argument, literally, is an argument “to the person.”) Both liberals and conservatives are the butt of this fallacy much too often. Not long after Barack Obama was elected to the Senate, Rush Limbaugh repeatedly referred to him as “Obama Osama” when criticizing the senator and the Democrats in general. -

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition ● A (normally) comical fallacy in which a proposition is backed by a premise or premises that are backed by the same proposition. Thus creating a cycle where no new or useful information is shared. Universal Example ● “Pvt. Joe Bowers: What are these electrolytes? Do you even know? Secretary of State: They're... what they use to make Brawndo! Pvt. Joe Bowers: But why do they use them to make Brawndo? Secretary of Defense: [raises hand after a pause] Because Brawndo's got electrolytes” (Example from logically fallicious.com from the movie Idiocracy). Circular Reasoning in The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Elizabeth Hale: But, woman, you do believe there are witches in- Explanation: Elizabeth believes that Elizabeth: If you think that I am one, there are no witches in Salem because then I say there are none. she knows that she is not a witch. She doesn’t think that she’s a witch (p. 200, act 2, lines 65-68) because she doesn’t believe that there are witches in Salem. And so on. More examples from The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Martha Martha Corey: I am innocent to a witch. I know not what a witch is. Explanation: This conversation Hawthorne: How do you know, then, between Martha and Hathorne is an that you are not a witch? example of begging the question. In Martha Corey: If I were, I would know it. Martha’s answer to Judge Hathorne, she uses false logic. -

The Fallacy of Composition and Meta-Argumentation"

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 10 May 22nd, 9:00 AM - May 25th, 5:00 PM Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro's "The fallacy of composition and meta-argumentation" Michel Dufour Sorbonne-Nouvelle, Institut de la Communication et des Médias Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Dufour, Michel, "Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro's "The fallacy of composition and meta- argumentation"" (2013). OSSA Conference Archive. 49. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA10/papersandcommentaries/49 This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commentary on: Maurice Finocchiaro’s “The fallacy of composition and meta-argumentation” MICHEL DUFOUR Department «Institut de la Communication et des Médias» Sorbonne-Nouvelle 13 rue Santeuil 75231 Paris Cedex 05 France [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION In his paper on the fallacy of composition, Maurice Finocchiaro puts forward several important theses about this fallacy. He also uses it to illustrate his view that fallacies should be studied in light of the notion of meta-argumentation at the core of his recent book (Finocchiaro, 2013). First, he expresses his puzzlement. Some authors have claimed that this fallacy is quite common (this is the ubiquity thesis) but it seems to have been neglected by scholars.