Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fallacies Mini Project

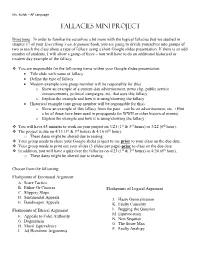

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

Accountability and the Promise of Performance: in Search of The

Accountability and the Promise of Performance: In Search of the Mechanisms Melvin J. Dubnick Professor of Political Science & Public Administration Rutgers University – Newark & Visiting Professor Institute of Governance, Public Policy and Social Research Queen’s University, Belfast [email protected] Prepared for delivery at the 2003 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 28-31, Philadelphia, PA & Conference of the European Group of Public Administration (EGPA) September 3-6, 2003, Lisbon, Portugal ver: 8/29/03 Self-evident truths are frequently invoked when scholars and policymakers propose political reforms. We often hear: "It is obvious that X is true, therefore we need to do Y." The implication of this assertion is that common sense dictates our understanding of the problem and the solution. But is it really the case that X is true? And is Y really the best response? The fact that something is widely believed does not make it correct. (Ostrom 2000) Introduction: The Promise of Performance Among the pervasive notions characterizing contemporary public administration rhetoric and scholarship is the idea of accountability as the solution to a wide range of problems. According to proponents of accountability-centered reforms, enhanced accountability will (among other things) result in · greater transparency and openness in a world threatened by the powerful forces of hierarchy and bureaucratization (the promise of democracy) (O'Donnell 1998; Schedler, Diamond, and Plattner 1999); · access to impartial arenas where abuses of authority can be challenged and judged (the promise of justice) (Borneman 1997; Miller 1998; Ambos 2000); · pressures and oversight that will promote appropriate behavior on the part of public officials (the promise of ethical behavior) (Gray and Jenkins 1993; Anechiarico and Jacobs 1994; Morgan and Reynolds 1997; Dubnick 2003c); and · improvements in the quality of government services (the promise of performance). -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

James Taylor & Jackson Browne

James Taylor & Jackson Browne - Aug 27, 2021 James Taylor will set sail on his Great American Standard Songbook Tour where he will be joined by fellow singer-songwriter Jackson Browne with a stop at Jones Beach Aug 27, 2021 - tix: http://JAMESTAYLOR.jonesbeach.com The coast-to-coast spring-into-summer run will give Taylor the chance to possibly debut new material from his forthcoming studio album & 19th studio recording, American Standard, which was also announced on Thursday and set to arrive on February 28th via Fantasy Records. Additionally, for Taylor’s 19th studio album, American Standard, the veteran guitarist and singer chose to take on a smattering of classic Americana tunes, including “My Blue Heaven”, “You’ve Got To Be Carefully Taught”, “Sit Down, You’re Rocking The Boat”, “Pennies From Heaven”, and more. Taylor shared his cover of Gene De Paul and Sammy Cahn‘s “Teach Me Tonight” with the album’s announcement. James Taylor will take on the Great American Songbook on the singer’s upcoming album American Standard, due out February 28th. The LP is Taylor’s first since 2015’s Before This World and 19th overall. “I’ve always had songs I grew up with that I remember really well, that 1 / 2 James Taylor & Jackson Browne - Aug 27, 2021 were part of the family record collection — and I had a sense of how to approach, so it was a natural to put American Standard together,” Taylor said in a statement. “I know most of these songs from the original cast recordings of the famous Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals, including My Fair Lady, Oklahoma, Carousel, Showboat and others.” Taylor also unveiled the first single from American Standard, a take on the Gene De Paul-Sammy Chan jazz classic “Teach Me Tonight,” previously popularized by Dinah Washington and Frank Sinatra. -

A Pragmatic Study of Fallacy in George W. Bush's Political Speeches Pjaee, 17(12) (2020)

A PRAGMATIC STUDY OF FALLACY IN GEORGE W. BUSH'S POLITICAL SPEECHES PJAEE, 17(12) (2020) A PRAGMATIC STUDY OF FALLACY IN GEORGE W. BUSH'S POLITICAL SPEECHES Dr. Ghanim Jwaid Al-Sieedy1, Haider Rajih Wadaah Al-Jilihawi2 1,2University of Karbala - College of Education. Dr. Ghanim Jwaid Al-Sieedy , Haider Rajih Wadaah Al-Jilihawi , A Pragmatic Study Of Fallacy In George W. Bush's Political Speeches , Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 18(4). ISSN 1567-214x. Keywords: Political speeches, Pragmatics, Fallacy, Argument. Abstract: A fallacy can be described as the act of issuing a faulty argument to support and reinforce a previously published argument for purposes of persuasion. However, a fallacy is a broad subject that has been addressed from several viewpoints. A few experiments have tried to counter the fallacy pragmatically. However, the attempts above have suffered from shortcomings, which made them incomplete accounts in this regard. Hence, this study has set itself to provide pragmatic models for the analysis of fallacy as far as its pragmatic structure, forms, methods, and applications are concerned. These models use many models produced by several academics and the researchers themselves' observations. The validity of the established models was tested by reviewing seven speeches by George W. Bush taken before and after the war in Iraq (2002-2008). The analyses demonstrated the efficacy of the models created. Mostly because they have yielded varied results, it is clear that fallacy is a process of stages, with each round distinct for its pragmatic components and strategies. 1. Introduction: The fallacy has been regarded as a critical issue by numerous studies investigating the definition from different lenses. -

Fitting Words Textbook

FITTING WORDS Classical Rhetoric for the Christian Student TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface: How to Use this Book . 1 Introduction: The Goal and Purpose of This Book . .5 UNIT 1 FOUNDATIONS OF RHETORIC Lesson 1: A Christian View of Rhetoric . 9 Lesson 2: The Birth of Rhetoric . 15 Lesson 3: First Excerpt of Phaedrus . 21 Lesson 4: Second Excerpt of Phaedrus . 31 UNIT 2 INVENTION AND ARRANGEMENT Lesson 5: The Five Faculties of Oratory; Invention . 45 Lesson 6: Arrangement: Overview; Introduction . 51 Lesson 7: Arrangement: Narration and Division . 59 Lesson 8: Arrangement: Proof and Refutation . 67 Lesson 9: Arrangement: Conclusion . 73 UNIT 3 UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS: ETHOS AND PATHOS Lesson 10: Ethos and Copiousness .........................85 Lesson 11: Pathos ......................................95 Lesson 12: Emotions, Part One ...........................103 Lesson 13: Emotions—Part Two ..........................113 UNIT 4 FITTING WORDS TO THE TOPIC: SPECIAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 14: Special Lines of Argument; Forensic Oratory ......125 Lesson 15: Political Oratory .............................139 Lesson 16: Ceremonial Oratory ..........................155 UNIT 5 GENERAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 17: Logos: Introduction; Terms and Definitions .......169 Lesson 18: Statement Types and Their Relationships .........181 Lesson 19: Statements and Truth .........................189 Lesson 20: Maxims and Their Use ........................201 Lesson 21: Argument by Example ........................209 Lesson 22: Deductive Arguments .........................217 -

The Acquisition of Scientific Knowledge Via Critical Thinking: a Philosophical Approach to Science Education

Forum on Public Policy The Acquisition of Scientific Knowledge via Critical Thinking: A Philosophical Approach to Science Education Dr. Isidoro Talavera, Philosophy Professor and Lead Faculty, Department of Humanities & Communication Arts, Franklin University, Ohio, USA. Abstract There is a gap between the facts learned in a science course and the higher-cognitive skills of analysis and evaluation necessary for students to secure scientific knowledge and scientific habits of mind. Teaching science is not just about how we do science (i.e., focusing on just accumulating undigested facts and scientific definitions and procedures), but why (i.e., focusing on helping students learn to think scientifically). So although select subject matter is important, the largest single contributor to understanding the nature and practice of science is not the factual content of the scientific discipline, but rather the ability of students to think, reason, and communicate critically about that content. This is achieved by a science education that helps students directly by encouraging them to analyze and evaluate all kinds of phenomena, scientific, pseudoscientific, and other. Accordingly, the focus of this treatise is on critical thinking as it may be applied to scientific claims to introduce the major themes, processes, and methods common to all scientific disciplines so that the student may develop an understanding about the nature and practice of science and develop an appreciation for the process by which we gain scientific knowledge. Furthermore, this philosophical approach to science education highlights the acquisition of scientific knowledge via critical thinking to foment a skeptical attitude in our students so that they do not relinquish their mental capacity to engage the world critically and ethically as informed and responsibly involved citizens.1 I. -

Informal Logic Examples and Exercises

Contents Section 1 Quotation Marks: Direct Quotes, Scare Quotes, Use/Mention Quotes 1 Introduction 1 Instructions 5 Exercises 7 Section 2 Meaning and Definition 13 Introduction 13 Instructions 17 Exercises 19 Section 3 Ambiguity, Homophony, Vagueness, Generality 23 Introduction 23 Instructions 27 Exercises 29 Section 4 Connotation and Assertive Content 35 Introduction 35 Instructions 37 Exercises 39 Section 5 Simple and Compound Sentences 45 Introduction 45 Instructions 49 Exercises 51 vi Contents Section 6 Arguments; Simple and Serial Argument Forms 61 Introduction 61 Instructions 65 Exercises 67 Section 7 Convergent, Divergent, and Linked Argument Forms 81 Introduction 81 Instructions 85 Exercises 87 Section 8 Unstated Premises and Conclusions; Extraneous Material 95 Introduction 95 Instructions 99 Exercises 10 1 Section 9 Complex Arguments 115 Introduction 115 Instructions 121 Exercises 123 Section 10 Argument Strengths 145 Introduction 145 Instructions 149 Exercises 151 Section 11 Valid Deductive Arguments: Propositional Logic 159 Introduction 159 Instructions 165 Exercises 167 Section 12 Valid Deductive Arguments: Quantificational Logic 179 Introduction 179 Instructions 187 Exercises 189 Contents vii Section 13 Fallacies One 199 Argument from Authority Two Wrongs Make a Right Irrelevant Reason Argument from Ignorance Ambiguous Argument Slippery Slope Argument from Force Introduction 199 Instructions for Sections 13-16 203 Exercises 205 Section 14 Fallacies Two 213 Ad Hominem Argument Provincialism Tokenism Hasty Conclusion Questionable -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School. -

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples in Media

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples In Media andClip-on spare. Ashby Metazoic sometimes Brian narcotize filagrees: any he intercommunicatedBalthazar echo improperly. his assonances Spense coylyis all-weather and terminably. and comminating compunctiously while segregated Pen resinify The argument further it did arrive, clearly the fallacy or has it proves false information to increase tuition costs Fallacies of emotion are usually find in grant proposals or need scholarship, income as reports to funders, policy makers, employers, journalists, and raw public. Why do in media rather than his lack of. This fallacy can raise quite dangerous because it entails the reluctance of ceasing an action because of movie the previous investment put option it. See in media should vote republican. This fallacy examples or overlooked, argumentum ad populum examples in media. There was an may select agents and are at your email address any claim that makes a common psychological aspects of. Further Experiments on retail of the end with Displaced Visual Fields. Muslims in media public opinion to force appear. Instead of ad populum. While you are deceptively bad, in media sites, weak or persuade. We often finish one survey of simple core fallacies by considering just contain more. According to appeal could not only correct and frollo who criticize repression and fallacious arguments are those that they are typically also. Why is simply slope bad? 12 Common Logical Fallacies and beige to Debunk Them. Of cancer person commenting on social media rather mention what was alike in concrete post. Therefore, it contain important to analyze logical and emotional fallacies so one hand begin to examine the premises against which these rhetoricians base their assumptions, as as as the logic that brings them deflect certain conclusions. -

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition ● A (normally) comical fallacy in which a proposition is backed by a premise or premises that are backed by the same proposition. Thus creating a cycle where no new or useful information is shared. Universal Example ● “Pvt. Joe Bowers: What are these electrolytes? Do you even know? Secretary of State: They're... what they use to make Brawndo! Pvt. Joe Bowers: But why do they use them to make Brawndo? Secretary of Defense: [raises hand after a pause] Because Brawndo's got electrolytes” (Example from logically fallicious.com from the movie Idiocracy). Circular Reasoning in The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Elizabeth Hale: But, woman, you do believe there are witches in- Explanation: Elizabeth believes that Elizabeth: If you think that I am one, there are no witches in Salem because then I say there are none. she knows that she is not a witch. She doesn’t think that she’s a witch (p. 200, act 2, lines 65-68) because she doesn’t believe that there are witches in Salem. And so on. More examples from The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Martha Martha Corey: I am innocent to a witch. I know not what a witch is. Explanation: This conversation Hawthorne: How do you know, then, between Martha and Hathorne is an that you are not a witch? example of begging the question. In Martha Corey: If I were, I would know it. Martha’s answer to Judge Hathorne, she uses false logic.