Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You Avoid the Central Point of an Argument, Instead Drawing Attention to a Minor (Or Side) Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fallacies Mini Project

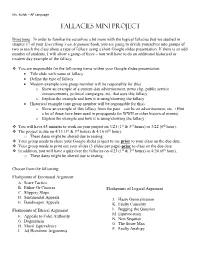

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

35 Fallacies

THIRTY-TWO COMMON FALLACIES EXPLAINED L. VAN WARREN Introduction If you watch TV, engage in debate, logic, or politics you have encountered the fallacies of: Bandwagon – "Everybody is doing it". Ad Hominum – "Attack the person instead of the argument". Celebrity – "The person is famous, it must be true". If you have studied how magicians ply their trade, you may be familiar with: Sleight - The use of dexterity or cunning, esp. to deceive. Feint - Make a deceptive or distracting movement. Misdirection - To direct wrongly. Deception - To cause to believe what is not true; mislead. Fallacious systems of reasoning pervade marketing, advertising and sales. "Get Rich Quick", phone card & real estate scams, pyramid schemes, chain letters, the list goes on. Because fallacy is common, you might want to recognize them. There is no world as vulnerable to fallacy as the religious world. Because there is no direct measure of whether a statement is factual, best practices of reasoning are replaced be replaced by "logical drift". Those who are political or religious should be aware of their vulnerability to, and exportation of, fallacy. The film, "Roshomon", by the Japanese director Akira Kurisawa, is an excellent study in fallacy. List of Fallacies BLACK-AND-WHITE Classifying a middle point between extremes as one of the extremes. Example: "You are either a conservative or a liberal" AD BACULUM Using force to gain acceptance of the argument. Example: "Convert or Perish" AD HOMINEM Attacking the person instead of their argument. Example: "John is inferior, he has blue eyes" AD IGNORANTIAM Arguing something is true because it hasn't been proven false. -

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases Examples of Argumentative Language Below are examples of signposts that are used in argumentative essays. Signposts enable the reader to follow our arguments easily. When pointing out opposing arguments (Cons): Opponents of this idea claim/maintain that… Those who disagree/ are against these ideas may say/ assert that… Some people may disagree with this idea, Some people may say that…however… When stating specifically why they think like that: They claim that…since… Reaching the turning point: However, But On the other hand, When refuting the opposing idea, we may use the following strategies: compromise but prove their argument is not powerful enough: - They have a point in thinking like that. - To a certain extent they are right. completely disagree: - After seeing this evidence, there is no way we can agree with this idea. say that their argument is irrelevant to the topic: - Their argument is irrelevant to the topic. Signposting sentences What are signposting sentences? Signposting sentences explain the logic of your argument. They tell the reader what you are going to do at key points in your assignment. They are most useful when used in the following places: In the introduction At the beginning of a paragraph which develops a new idea At the beginning of a paragraph which expands on a previous idea At the beginning of a paragraph which offers a contrasting viewpoint At the end of a paragraph to sum up an idea In the conclusion A table of signposting stems: These should be used as a guide and as a way to get you thinking about how you present the thread of your argument. -

False Dilemma Wikipedia Contents

False dilemma Wikipedia Contents 1 False dilemma 1 1.1 Examples ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Morton's fork ......................................... 1 1.1.2 False choice .......................................... 2 1.1.3 Black-and-white thinking ................................... 2 1.2 See also ................................................ 2 1.3 References ............................................... 3 1.4 External links ............................................. 3 2 Affirmative action 4 2.1 Origins ................................................. 4 2.2 Women ................................................ 4 2.3 Quotas ................................................. 5 2.4 National approaches .......................................... 5 2.4.1 Africa ............................................ 5 2.4.2 Asia .............................................. 7 2.4.3 Europe ............................................ 8 2.4.4 North America ........................................ 10 2.4.5 Oceania ............................................ 11 2.4.6 South America ........................................ 11 2.5 International organizations ...................................... 11 2.5.1 United Nations ........................................ 12 2.6 Support ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Polls .............................................. 12 2.7 Criticism ............................................... 12 2.7.1 Mismatching ......................................... 13 2.8 See also -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School. -

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition ● A (normally) comical fallacy in which a proposition is backed by a premise or premises that are backed by the same proposition. Thus creating a cycle where no new or useful information is shared. Universal Example ● “Pvt. Joe Bowers: What are these electrolytes? Do you even know? Secretary of State: They're... what they use to make Brawndo! Pvt. Joe Bowers: But why do they use them to make Brawndo? Secretary of Defense: [raises hand after a pause] Because Brawndo's got electrolytes” (Example from logically fallicious.com from the movie Idiocracy). Circular Reasoning in The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Elizabeth Hale: But, woman, you do believe there are witches in- Explanation: Elizabeth believes that Elizabeth: If you think that I am one, there are no witches in Salem because then I say there are none. she knows that she is not a witch. She doesn’t think that she’s a witch (p. 200, act 2, lines 65-68) because she doesn’t believe that there are witches in Salem. And so on. More examples from The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Martha Martha Corey: I am innocent to a witch. I know not what a witch is. Explanation: This conversation Hawthorne: How do you know, then, between Martha and Hathorne is an that you are not a witch? example of begging the question. In Martha Corey: If I were, I would know it. Martha’s answer to Judge Hathorne, she uses false logic. -

4 Quantifiers and Quantified Arguments 4.1 Quantifiers

4 Quantifiers and Quantified Arguments 4.1 Quantifiers Recall from Chapter 3 the definition of a predicate as an assertion con- taining one or more variables such that, if the variables are replaced by objects from a given Universal set U then we obtain a proposition. Let p(x) be a predicate with one variable. Definition If for all x ∈ U, p(x) is true, we write ∀x : p(x). ∀ is called the universal quantifier. Definition If there exists x ∈ U such that p(x) is true, we write ∃x : p(x). ∃ is called the existential quantifier. Note (1) ∀x : p(x) and ∃x : p(x) are propositions and so, in any given example, we will be able to assign truth-values. (2) The definitions can be applied to predicates with two or more vari- ables. So if p(x, y) has two variables we have, for instance, ∀x, ∃y : p(x, y) if “for all x there exists y for which p(x, y) is holds”. (3) Let A and B be two sets in a Universal set U. Recall the definition of A ⊆ B as “every element of A is in B.” This is a “for all” statement so we should be able to symbolize it. We do so by first rewriting the definition as “for all x ∈ U, if x is in A then x is in B, ” which in symbols is ∀x ∈ U : if (x ∈ A) then (x ∈ B) , or ∀x :(x ∈ A) → (x ∈ B) . 1 (4*) Recall that a variable x in a propositional form p(x) is said to be free. -

Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I All effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare necessities and then must be expressed in a few stereotyped formulas. Adolf Hitler Until the habit of thinking is well formed, facing the situation to discover the facts requires an effort. For the mind tends to dislike what is unpleasant and so to sheer off from an adequate notice of that which is especially annoying. John Dewey, How We Think Introduction In everyday speech you may have heard someone refer to a commonly accepted belief as a fallacy. What is usually meant is that the belief is false, although widely accepted. In logic, a fallacy refers to logically weak argument appeal (not a belief or statement) that is widely used and successful. Here is our definition: A logical fallacy is an argument that is usually psychologically persuasive but logically weak. By this definition we mean that fallacious arguments work in getting many people to accept conclusions, that they make bad arguments appear good even though a little commonsense reflection will reveal that people ought not to accept the conclusions of these arguments as strongly supported. Although logicians distinguish between formal and informal fallacies, our focus in this chapter and the next one will be on traditional informal fallacies.1 For our purposes, we can think of these fallacies as "informal" because they are most often found in the everyday exchanges of ideas, such as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, political speeches, advertisements, conversational disagreements between people in social networking sites and Internet discussion boards, and so on. -

Is 'Argument' Subject to the Product/Process Ambiguity?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Philosophy Faculty Publications Philosophy 2011 Is ‘argument’ subject to the product/process ambiguity? G. C. Goddu University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/philosophy-faculty- publications Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Goddu, G. C. "Is ‘argument’ Subject to the Product/process Ambiguity?" Informal Logic 31, no. 2 (2011): 75-88. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Is ‘argument’ subject to the product/process ambiguity? G.C. GODDU Department of Philosophy University of Richmond Richmond, VA 23173 U.S.A. [email protected] Abstract: The product/process dis- Resumé: La distinction proces- tinction with regards to “argument” sus/produit appliquée aux arguments has a longstanding history and foun- joue un rôle de fondement de la dational role in argumentation the- théorie de l’argumentation depuis ory. I shall argue that, regardless of longtemps. Quelle que soit one’s chosen ontology of arguments, l’ontologie des arguments qu’on arguments are not the product of adopte, je soutiens que les argu- some process of arguing. Hence, ments ne sont pas le produit d’un appeal to the distinction is distorting processus d’argumentation. Donc the very organizational foundations l’usage de cette distinction déforme of argumentation theory and should le fondement organisationnel de la be abandoned. -

The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law , 65 Fla

Florida Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 6 Article 1 October 2013 The rT espass Fallacy in Patent Law Adam Mossoff Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Adam Mossoff, The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law , 65 Fla. L. Rev. 1687 (2013). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol65/iss6/1 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mossoff: The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law Florida Law Review Founded 1948 VOLUME 65 DECEMBER 2013 NUMBER 6 ESSAYS THE TRESPASS FALLACY IN PATENT LAW Adam Mossoff∗ Abstract The patent system is broken and in dire need of reform; so says the popular press, scholars, lawyers, judges, congresspersons, and even the President. One common complaint is that patents are now failing as property rights because their boundaries are not as clear as the fences that demarcate real estate—patent infringement is neither as determinate nor as efficient as trespass is for land. This Essay explains that this is a fallacious argument, suffering both empirical and logical failings. Empirically, there are no formal studies of trespass litigation rates; thus, complaints about the patent system’s indeterminacy are based solely on an idealized theory of how trespass should function, which economists identify as the “nirvana fallacy.” Furthermore, anecdotal evidence and other studies suggest that boundary disputes between landowners are neither as clear nor as determinate as patent scholars assume them to be. -

The Big Lie” Feedback Responses

2016 Two More Chains Fall Issue “The Big Lie” Feedback Responses Do you agree or disagree Please elaborate on why you What’s the next step? How do we bring opposing with “The Big Lie” agree or disagree. views together? concepts? Why? 1. (Respondent selected “Other” for job position.) [No Input] Learn how to read wildfires. Agree. Underestimating potential leads to Based on “Personal Experience.” accidents. 2. Firefighter I have over 33 years’ experience working We need to discuss revising the entry level training programs to Agree. for All Risk Fire Departments in California include this information and focus more on the intent of the Fire Based on “Personal Experience.” including CAL FIRE. Qualified as DIVS, Orders (not just memorizing) what they really mean—and how to SOFR, STCR, FAL1 to name a few. mitigate risk to acceptable levels before we engage. Through this experience and studies I What happened to S-133 and S-134? Have these course been have long ago formed the following eliminated and if so why? opinions: With the risk management process, we seek to mitigate risk, but cannot always remove risk. Therefore, manage the risk and decide if the mitigations are acceptable before we engage. I also agree that there is a culture to memorize and recognize the Standard Fire Orders, but in practice the culture does not fully support following the orders or complying with the intent of the orders. With this type of culture, we often set ourselves up for the opportunity to experience catastrophic results. 1 Do you agree or disagree Please elaborate on why you What’s the next step? How do we bring opposing with “The Big Lie” agree or disagree.