The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fallacies Mini Project

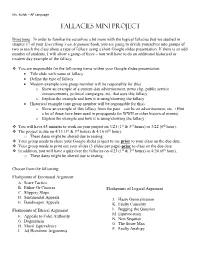

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases Examples of Argumentative Language Below are examples of signposts that are used in argumentative essays. Signposts enable the reader to follow our arguments easily. When pointing out opposing arguments (Cons): Opponents of this idea claim/maintain that… Those who disagree/ are against these ideas may say/ assert that… Some people may disagree with this idea, Some people may say that…however… When stating specifically why they think like that: They claim that…since… Reaching the turning point: However, But On the other hand, When refuting the opposing idea, we may use the following strategies: compromise but prove their argument is not powerful enough: - They have a point in thinking like that. - To a certain extent they are right. completely disagree: - After seeing this evidence, there is no way we can agree with this idea. say that their argument is irrelevant to the topic: - Their argument is irrelevant to the topic. Signposting sentences What are signposting sentences? Signposting sentences explain the logic of your argument. They tell the reader what you are going to do at key points in your assignment. They are most useful when used in the following places: In the introduction At the beginning of a paragraph which develops a new idea At the beginning of a paragraph which expands on a previous idea At the beginning of a paragraph which offers a contrasting viewpoint At the end of a paragraph to sum up an idea In the conclusion A table of signposting stems: These should be used as a guide and as a way to get you thinking about how you present the thread of your argument. -

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition ● A (normally) comical fallacy in which a proposition is backed by a premise or premises that are backed by the same proposition. Thus creating a cycle where no new or useful information is shared. Universal Example ● “Pvt. Joe Bowers: What are these electrolytes? Do you even know? Secretary of State: They're... what they use to make Brawndo! Pvt. Joe Bowers: But why do they use them to make Brawndo? Secretary of Defense: [raises hand after a pause] Because Brawndo's got electrolytes” (Example from logically fallicious.com from the movie Idiocracy). Circular Reasoning in The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Elizabeth Hale: But, woman, you do believe there are witches in- Explanation: Elizabeth believes that Elizabeth: If you think that I am one, there are no witches in Salem because then I say there are none. she knows that she is not a witch. She doesn’t think that she’s a witch (p. 200, act 2, lines 65-68) because she doesn’t believe that there are witches in Salem. And so on. More examples from The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Martha Martha Corey: I am innocent to a witch. I know not what a witch is. Explanation: This conversation Hawthorne: How do you know, then, between Martha and Hathorne is an that you are not a witch? example of begging the question. In Martha Corey: If I were, I would know it. Martha’s answer to Judge Hathorne, she uses false logic. -

4 Quantifiers and Quantified Arguments 4.1 Quantifiers

4 Quantifiers and Quantified Arguments 4.1 Quantifiers Recall from Chapter 3 the definition of a predicate as an assertion con- taining one or more variables such that, if the variables are replaced by objects from a given Universal set U then we obtain a proposition. Let p(x) be a predicate with one variable. Definition If for all x ∈ U, p(x) is true, we write ∀x : p(x). ∀ is called the universal quantifier. Definition If there exists x ∈ U such that p(x) is true, we write ∃x : p(x). ∃ is called the existential quantifier. Note (1) ∀x : p(x) and ∃x : p(x) are propositions and so, in any given example, we will be able to assign truth-values. (2) The definitions can be applied to predicates with two or more vari- ables. So if p(x, y) has two variables we have, for instance, ∀x, ∃y : p(x, y) if “for all x there exists y for which p(x, y) is holds”. (3) Let A and B be two sets in a Universal set U. Recall the definition of A ⊆ B as “every element of A is in B.” This is a “for all” statement so we should be able to symbolize it. We do so by first rewriting the definition as “for all x ∈ U, if x is in A then x is in B, ” which in symbols is ∀x ∈ U : if (x ∈ A) then (x ∈ B) , or ∀x :(x ∈ A) → (x ∈ B) . 1 (4*) Recall that a variable x in a propositional form p(x) is said to be free. -

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You Avoid the Central Point of an Argument, Instead Drawing Attention to a Minor (Or Side) Issue

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You avoid the central point of an argument, instead drawing attention to a minor (or side) issue. ex. You've put through a proposal that will cut overall loan benefits for students and drastically raise interest rates, but then you focus on how the system will be set up to process loan applications for students more quickly. Ad hominem: Here you attack a person's character, physical appearance, or personal habits instead of addressing the central issues of an argument. You focus on the person's personality, rather than on his/her ideas, evidence, or arguments. This type of attack sometimes comes in the form of character assassination (especially in politics). You must be sure that character is, in fact, a relevant issue. ex. How can we elect John Smith as the new CEO of our department store when he has been through 4 messy divorces due to his infidelity? Ad populum: This type of argument uses illegitimate emotional appeal, drawing on people's emotions, prejudices, and stereotypes. The emotion evoked here is not supported by sufficient, reliable, and trustworthy sources. Ex. We shouldn't develop our shopping mall here in East Vancouver because there is a rather large immigrant population in the area. There will be too much loitering, shoplifting, crime, and drug use. Complex or Loaded Question: Offers only two options to answer a question that may require a more complex answer. Such questions are worded so that any answer will implicate an opponent. Ex. At what point did you stop cheating on your wife? Setting up a Straw Person: Here you address the weakest point of an opponent's argument, instead of focusing on a main issue. -

Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I

Essential Logic Ronald C. Pine Chapter 4: INFORMAL FALLACIES I All effective propaganda must be confined to a few bare necessities and then must be expressed in a few stereotyped formulas. Adolf Hitler Until the habit of thinking is well formed, facing the situation to discover the facts requires an effort. For the mind tends to dislike what is unpleasant and so to sheer off from an adequate notice of that which is especially annoying. John Dewey, How We Think Introduction In everyday speech you may have heard someone refer to a commonly accepted belief as a fallacy. What is usually meant is that the belief is false, although widely accepted. In logic, a fallacy refers to logically weak argument appeal (not a belief or statement) that is widely used and successful. Here is our definition: A logical fallacy is an argument that is usually psychologically persuasive but logically weak. By this definition we mean that fallacious arguments work in getting many people to accept conclusions, that they make bad arguments appear good even though a little commonsense reflection will reveal that people ought not to accept the conclusions of these arguments as strongly supported. Although logicians distinguish between formal and informal fallacies, our focus in this chapter and the next one will be on traditional informal fallacies.1 For our purposes, we can think of these fallacies as "informal" because they are most often found in the everyday exchanges of ideas, such as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, political speeches, advertisements, conversational disagreements between people in social networking sites and Internet discussion boards, and so on. -

Is 'Argument' Subject to the Product/Process Ambiguity?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Philosophy Faculty Publications Philosophy 2011 Is ‘argument’ subject to the product/process ambiguity? G. C. Goddu University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/philosophy-faculty- publications Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Goddu, G. C. "Is ‘argument’ Subject to the Product/process Ambiguity?" Informal Logic 31, no. 2 (2011): 75-88. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Is ‘argument’ subject to the product/process ambiguity? G.C. GODDU Department of Philosophy University of Richmond Richmond, VA 23173 U.S.A. [email protected] Abstract: The product/process dis- Resumé: La distinction proces- tinction with regards to “argument” sus/produit appliquée aux arguments has a longstanding history and foun- joue un rôle de fondement de la dational role in argumentation the- théorie de l’argumentation depuis ory. I shall argue that, regardless of longtemps. Quelle que soit one’s chosen ontology of arguments, l’ontologie des arguments qu’on arguments are not the product of adopte, je soutiens que les argu- some process of arguing. Hence, ments ne sont pas le produit d’un appeal to the distinction is distorting processus d’argumentation. Donc the very organizational foundations l’usage de cette distinction déforme of argumentation theory and should le fondement organisationnel de la be abandoned. -

The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law , 65 Fla

Florida Law Review Volume 65 | Issue 6 Article 1 October 2013 The rT espass Fallacy in Patent Law Adam Mossoff Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Intellectual Property Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Adam Mossoff, The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law , 65 Fla. L. Rev. 1687 (2013). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol65/iss6/1 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mossoff: The Trespass Fallacy in Patent Law Florida Law Review Founded 1948 VOLUME 65 DECEMBER 2013 NUMBER 6 ESSAYS THE TRESPASS FALLACY IN PATENT LAW Adam Mossoff∗ Abstract The patent system is broken and in dire need of reform; so says the popular press, scholars, lawyers, judges, congresspersons, and even the President. One common complaint is that patents are now failing as property rights because their boundaries are not as clear as the fences that demarcate real estate—patent infringement is neither as determinate nor as efficient as trespass is for land. This Essay explains that this is a fallacious argument, suffering both empirical and logical failings. Empirically, there are no formal studies of trespass litigation rates; thus, complaints about the patent system’s indeterminacy are based solely on an idealized theory of how trespass should function, which economists identify as the “nirvana fallacy.” Furthermore, anecdotal evidence and other studies suggest that boundary disputes between landowners are neither as clear nor as determinate as patent scholars assume them to be. -

What Is Racial Domination?

STATE OF THE ART WHAT IS RACIAL DOMINATION? Matthew Desmond Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison Mustafa Emirbayer Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin—Madison Abstract When students of race and racism seek direction, they can find no single comprehensive source that provides them with basic analytical guidance or that offers insights into the elementary forms of racial classification and domination. We believe the field would benefit greatly from such a source, and we attempt to offer one here. Synchronizing and building upon recent theoretical innovations in the area of race, we lend some conceptual clarification to the nature and dynamics of race and racial domination so that students of the subjects—especially those seeking a general (if economical) introduction to the vast field of race studies—can gain basic insight into how race works as well as effective (and fallacious) ways to think about racial domination. Focusing primarily on the American context, we begin by defining race and unpacking our definition. We then describe how our conception of race must be informed by those of ethnicity and nationhood. Next, we identify five fallacies to avoid when thinking about racism. Finally, we discuss the resilience of racial domination, concentrating on how all actors in a society gripped by racism reproduce the conditions of racial domination, as well as on the benefits and drawbacks of approaches that emphasize intersectionality. Keywords: Race, Race Theory, Racial Domination, Inequality, Intersectionality INTRODUCTION Synchronizing and building upon recent theoretical innovations in the area of race, we lend some conceptual clarification to the nature and dynamics of race and racial domination, providing in a single essay a source through which thinkers—especially those seeking a general ~if economical! introduction to the vast field of race studies— can gain basic insight into how race works as well as effective ways to think about racial domination. -

Ambiguity in Argument Jan Albert Van Laar*

Argument and Computation Vol. 1, No. 2, June 2010, 125–146 Ambiguity in argument Jan Albert van Laar* Department of Theoretical Philosophy, University of Groningen, Groningen 9712 GL, The Netherlands (Received 8 September 2009; final version received 11 February 2010) The use of ambiguous expressions in argumentative dialogues can lead to misunderstanding and equivocation. Such ambiguities are here called active ambiguities. However, even a normative model of persuasion dialogue ought not to ban active ambiguities altogether, one reason being that it is not always possible to determine beforehand which expressions will prove to be actively ambiguous. Thus, it is proposed that argumentative norms should enable each participant to put forward ambiguity criticisms as well as self-critical ambiguity corrections, inducing them to improve their language if necessary. In order to discourage them from nitpicking and from arriving at excessively high levels of precision, the parties are also provided with devices with which to examine whether the ambiguity corrections or ambiguity criticisms have been appropriate. A formal dialectical system is proposed, in the Hamblin style, that satisfies these and some other philosophical desiderata. Keywords: active ambiguity; argument; critical discussion; equivocation; persuasion dialogue; pseudo-agreement; pseudo-disagreement 1. Introduction Argumentative types of dialogue can be hampered by expressions that are ambiguous or equivocal. A participant can show dissatisfaction with such ambiguities by disambiguating the formulations he has used or by inciting the other side to improve upon their formulations. A typical example can be found in the case where W.B. had been arrested both for drink and driving and for driving under suspension. -

334 CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES a Deductive Fallacy Is

CHAPTER 7 INFORMAL FALLACIES A deductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument necessarily follows from the truth of the premises given, when in fact that conclusion does not necessarily follow from those premises. An inductive fallacy is committed whenever it is suggested that the truth of the conclusion of an argument is made more probable by its relationship with the premises of the argument, when in fact it is not. We will cover two kinds of fallacies: formal fallacies and informal fallacies. An argument commits a formal fallacy if it has an invalid argument form. An argument commits an informal fallacy when it has a valid argument form but derives from unacceptable premises. A. Fallacies with Invalid Argument Forms Consider the following arguments: (1) All Europeans are racist because most Europeans believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans and all people who believe that Africans are inferior to Europeans are racist. (2) Since no dogs are cats and no cats are rats, it follows that no dogs are rats. (3) If today is Thursday, then I'm a monkey's uncle. But, today is not Thursday. Therefore, I'm not a monkey's uncle. (4) Some rich people are not elitist because some elitists are not rich. 334 These arguments have the following argument forms: (1) Some X are Y All Y are Z All X are Z. (2) No X are Y No Y are Z No X are Z (3) If P then Q not-P not-Q (4) Some E are not R Some R are not E Each of these argument forms is deductively invalid, and any actual argument with such a form would be fallacious. -

Lecture 1: Propositional Logic

Lecture 1: Propositional Logic Syntax Semantics Truth tables Implications and Equivalences Valid and Invalid arguments Normal forms Davis-Putnam Algorithm 1 Atomic propositions and logical connectives An atomic proposition is a statement or assertion that must be true or false. Examples of atomic propositions are: “5 is a prime” and “program terminates”. Propositional formulas are constructed from atomic propositions by using logical connectives. Connectives false true not and or conditional (implies) biconditional (equivalent) A typical propositional formula is The truth value of a propositional formula can be calculated from the truth values of the atomic propositions it contains. 2 Well-formed propositional formulas The well-formed formulas of propositional logic are obtained by using the construction rules below: An atomic proposition is a well-formed formula. If is a well-formed formula, then so is . If and are well-formed formulas, then so are , , , and . If is a well-formed formula, then so is . Alternatively, can use Backus-Naur Form (BNF) : formula ::= Atomic Proposition formula formula formula formula formula formula formula formula formula formula 3 Truth functions The truth of a propositional formula is a function of the truth values of the atomic propositions it contains. A truth assignment is a mapping that associates a truth value with each of the atomic propositions . Let be a truth assignment for . If we identify with false and with true, we can easily determine the truth value of under . The other logical connectives can be handled in a similar manner. Truth functions are sometimes called Boolean functions. 4 Truth tables for basic logical connectives A truth table shows whether a propositional formula is true or false for each possible truth assignment.