Dancing Double Binds: Feminine Virtue and Women's Work in Kinshasa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Nathan Oyori Ogechi aus Kenia Hamburg 2002 ii 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt Datum der Disputation: 15. November 2002 iii Acknowledgement I am indebted to many people for their support and encouragement. It is not possible to mention all by name. However, it would be remiss of me not to name some of them because their support was too conspicuous. I am bereft of words with which to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh for accepting to supervise my research and her selflessness that enabled me secure further funding at the expiry of my one-year scholarship. Her thoroughness and meticulous supervision kept me on toes. I am also indebted to Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt for reading my error-ridden draft. I appreciate the support I received from everybody at the Afrika-Abteilung, Universität Hamburg, namely Dr. Roland Kießling, Theda Schumann, Dr. Jutta Becher, Christiane Simon, Christine Pawlitzky and the institute librarian, Frau Carmen Geisenheyner. Professors Myers-Scotton, Kamwangamalu, Clyne and Auer generously sent me reading materials whenever I needed them. Thank you Dr. Irmi Hanak at Afrikanistik, Vienna, Ndugu Abdulatif Abdalla of Leipzig and Bi. Sauda Samson of Hamburg. I thank the DAAD for initially funding my stay in Deutschland. Professors Miehe and Khamis of Bayreuth must be thanked for their selfless support. I appreciate the kind support I received from the Akademisches Auslandsamt, University of Hamburg. -

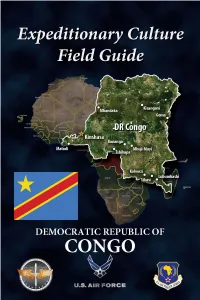

ECFG-DRC-2020R.Pdf

ECFG About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally t complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The he fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. Democratic Republicof The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), focusing on unique cultural features of the DRC’s society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN © Siegfried Modola). the For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact Congo AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

“Indépendance Cha Cha”: African Pop Music Since the Independence Era, In: Africa Spectrum, 45, 3, 131-146

Africa Spectrum Dorsch, Hauke (2010), “Indépendance Cha Cha”: African Pop Music since the Independence Era, in: Africa Spectrum, 45, 3, 131-146. ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs in co-operation with the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To subscribe to the print edition: <[email protected]> For an e-mail alert please register at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Africa Spectrum is part of the GIGA Journal Family which includes: Africa Spectrum • Journal of Current Chinese Affairs • Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs • Journal of Politics in Latin America • <www.giga-journal-family.org> Africa Spectrum 3/2010: 131-146 “Indépendance Cha Cha”: African Pop Music since the Independence Era Hauke Dorsch Abstract: Investigating why Latin American music came to be the sound- track of the independence era, this contribution offers an overview of musi- cal developments and cultural politics in certain sub-Saharan African coun- tries since the 1960s. Focusing first on how the governments of newly inde- pendent African states used musical styles and musicians to support their nation-building projects, the article then looks at musicians’ more recent perspectives on the independence era. Manuscript received 17 November 2010; 21 February 2011 Keywords: Africa, music, socio-cultural change Hauke Dorsch teaches cultural anthropology at Johannes Gutenberg Uni- versity in Mainz, Germany, where he also serves as the director of the Afri- can Music Archive. -

Dec 19, 2015 Fondation Cartier Traces the Creative Spirit of the Democratic Republic of the Congo Fondation Cartier Traces the C

dec 19, 2015 fondation cartier traces the creative spirit of the democratic republic of the congo fondation cartier traces the creative spirit of the democratic republic of the congo monsengo shula, ‘ata ndele mokili ekobaluka (tôt ou tard le monde changera)’, 2014 acrylic and glitters on canvas, 130 x 200 cm private collection © monsengo shula photo © florian kleinefen beauté congo – 1926-2015 – congo kitoko fondation cartier, paris on now until january 10th, 2016 the creative spirit of the democratic republic of the congo is celebrated in a special exhibition hosted at the fondation cartier in paris. curated by andré magnin, ‘beauté congo – 1926-2015 – congo kitoko’ highlights the birth of modern painting practices in the african nation beginning in the 1920s, and traces almost a century of the country’s artistic production. while the focus is on painting, the show also includes comics, music, photography and sculpture, offering the public a unique opportunity in which to discover and experience the diverse and vibrant art scene of the region. monsengo shula, ‘ata ndele mokili ekobaluka (tôt ou tard le monde changera)’, 2014 (detail) image © designboom 1 in the mid-1920s, when the congo was still a belgian colony, precursors such as albert and antoinette lubacki, and djilatendo painted the first known congolese works on paper, opening the door to the modern and contemporary art scene in the country. figurative and geometric in style, their works depicted village life, the natural world, dreams and legends expressed with great poetry and imagination. following world war II, french painter pierre romain-desfossés moved to the congo and established an art workshop called atelier du hangar, where until his death in 1954, painters such as bela sar, mwenze kibwanga and pili pili mulongoy learned to freely exercise their imaginations, creating colorful and enchanting works in their own inventive and distinctive styles. -

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2015 Studio Magazine Board of Trustees This Issue of Studio Is Underwritten, Editor-In-Chief Raymond J

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2015 Studio magazine Board of Trustees This issue of Studio is underwritten, Editor-in-Chief Raymond J. McGuire, Chairman in part, with support from Elizabeth Gwinn Carol Sutton Lewis, Vice-Chair Rodney M. Miller, Treasurer Creative Director The Studio Museum in Harlem is sup- Thelma Golden Dr. Anita Blanchard ported, in part, with public funds provided Jacqueline L. Bradley Managing Editor by the following government agencies and Valentino D. Carlotti Dana Liss elected representatives: Kathryn C. Chenault Joan S. Davidson Copy Editor The New York City Department of Cultural Gordon J. Davis, Esq. Samir S. Patel Aairs; New York State Council on the Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Arts, a state agency; National Endowment Design Sandra Grymes for the Arts; the New York City Council; Pentagram Arthur J. Humphrey Jr. and the Manhattan Borough President. George L. Knox Printing Nancy L. Lane Allied Printing Services The Studio Museum in Harlem is deeply Dr. Michael L. Lomax grateful to the following institutional do- Original Design Concept Bernard I. Lumpkin nors for their leadership support: 2X4, Inc. Dr. Amelia Ogunlesi Ann G. Tenenbaum Studio is published two times a year Bloomberg Philanthropies John T. Thompson by The Studio Museum in Harlem, Booth Ferris Foundation Reginald Van Lee 144 W. 125th St., New York, NY 10027. Ed Bradley Family Foundation The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Hon. Bill de Blasio, ex-oicio Copyright ©2015 Studio magazine. Charitable Trust Hon. Tom Finkelpearl, ex-oicio Ford Foundation All rights, including translation into other The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation languages, are reserved by the publisher. -

Culture and Customs of Kenya

Culture and Customs of Kenya NEAL SOBANIA GREENWOOD PRESS Culture and Customs of Kenya Cities and towns of Kenya. Culture and Customs of Kenya 4 NEAL SOBANIA Culture and Customs of Africa Toyin Falola, Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sobania, N. W. Culture and customs of Kenya / Neal Sobania. p. cm.––(Culture and customs of Africa, ISSN 1530–8367) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–31486–1 (alk. paper) 1. Ethnology––Kenya. 2. Kenya––Social life and customs. I. Title. II. Series. GN659.K4 .S63 2003 305.8´0096762––dc21 2002035219 British Library Cataloging in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2003 by Neal Sobania All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2002035219 ISBN: 0–313–31486–1 ISSN: 1530–8367 First published in 2003 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 For Liz Contents Series Foreword ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Chronology xvii 1 Introduction 1 2 Religion and Worldview 33 3 Literature, Film, and Media 61 4 Art, Architecture, and Housing 85 5 Cuisine and Traditional Dress 113 6 Gender Roles, Marriage, and Family 135 7 Social Customs and Lifestyle 159 8 Music and Dance 187 Glossary 211 Bibliographic Essay 217 Index 227 Series Foreword AFRICA is a vast continent, the second largest, after Asia. -

P32:Layout 1

TV PROGRAMS MONDAY, DECEMBER 2, 2013 Impossible 04:50 Suite Life On Deck 01:45 Dynamo: Magician 05:15 Wizards Of Waverly Place Impossible 05:35 Wizards Of Waverly Place 02:35 Dynamo: Magician 06:00 Austin And Ally John Galliano’s 00:20 Paradox Impossible 06:25 Austin And Ally 01:15 Hebburn 03:25 Dynamo: Magician 06:45 A.N.T. Farm case to be heard in 01:45 Absolutely Fabulous Impossible 07:10 A.N.T. Farm 02:15 Spooks 04:15 Dynamo: Magician 07:35 Gravity Falls a labour court 03:05 Last Of The Summer Wine Impossible 07:55 My Babysitter’s A Vampire 03:35 Luther 05:05 Dynamo: Magician 08:20 Sofia The First 04:30 Hebburn Impossible 08:45 Doc McStuffins ohn Galliano’s case against former employers 05:00 Nina And The Neurons 06:00 Mythbusters 09:05 Mickey Mouse Clubhouse Christian Dior Couture SA and John Galliano SA 07:00 Mythbusters 09:30 Shake It Up J 05:15 Poetry Pie will be heard in a labour court. The Paris Court of 07:50 Extreme Fishing 09:55 Austin And Ally 05:20 Mr Bloom’s Nursery Appeals rejected an appeal by Dior, which was seek- 05:40 Little Human Planet 08:40 Overhaulin’ 2012 10:15 A.N.T. Farm 10:40 Dog With A Blog ing to move the case to a commercial court, and 05:45 Bobinogs 09:30 Border Security 11:05 Jessie 05:55 Tweenies 09:55 Storage Hunters ordered the companies to each pay the fashion 11:25 Suite Life On Deck € 06:15 Nina And The Neurons 10:20 Property Wars designer 2,500, in addition to court costs. -

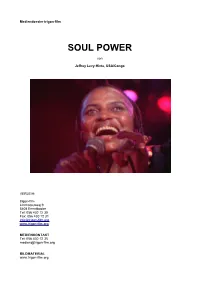

Pd Soul Power D

Mediendossier trigon-film SOUL POWER von Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, USA/Congo VERLEIH: trigon-film Limmatauweg 9 5408 Ennetbaden Tel: 056 430 12 30 Fax: 056 430 12 31 [email protected] www.trigon-film.org MEDIENKONTAKT Tel: 056 430 12 35 [email protected] BILDMATERIAL www.trigon-film.org MITWIRKENDE Regie: Jeffrey Levy-Hinte Kamera: Paul Goldsmith Kevin Keating Albert Maysles Roderick Young Montage: David Smith Produzenten: David Sonenberg, Leon Gast Produzenten Musikfestival Hugh Masekela, Stewart Levine Dauer: 93 Minuten Sprache/UT: Englisch/Französisch/d/f MUSIKER/ IN DER REIHENFOLGE IHRES ERSCHEINENS “Godfather of Soul” James Brown J.B.’s Bandleader & Trombonist Fred Wesley J.B.’s Saxophonist Maceo Parker Festival / Fight Promoter Don King “The Greatest” Muhammad Ali Concert Lighting Director Bill McManus Festival Coordinator Alan Pariser Festival Promoter Stewart Levine Festival Promoter Lloyd Price Investor Representative Keith Bradshaw The Spinners Henry Fambrough Billy Henderson Pervis Jackson Bobbie Smith Philippé Wynne “King of the Blues” B.B. King Singer/Songwriter Bill Withers Fania All-Stars Guitarist Yomo Toro “La Reina de la Salsa” Celia Cruz Fania All-Stairs Bandleader & Flautist Johnny Pacheco Trio Madjesi Mario Matadidi Mabele Loko Massengo "Djeskain" Saak "Sinatra" Sakoul, Festival Promoter Hugh Masakela Author & Editor George Plimpton Photographer Lynn Goldsmith Black Nationalist Stokely Carmichael a.k.a. “Kwame Ture” Ali’s Cornerman Drew “Bundini” Brown J.B.’s Singer and Bassist “Sweet" Charles Sherrell J.B.’s Dancers — “The Paybacks” David Butts Lola Love Saxophonist Manu Dibango Music Festival Emcee Lukuku OK Jazz Lead Singer François “Franco” Luambo Makiadi Singer Miriam Makeba Spinners and Sister Sledge Manager Buddy Allen Sister Sledge Debbie Sledge Joni Sledge Kathy Sledge Kim Sledge The Crusaders Kent Leon Brinkley Larry Carlton Wilton Felder Wayne Henderson Stix Hooper Joe Sample Fania All-Stars Conga Player Ray Barretto Fania All Stars Timbali Player Nicky Marrero Conga Musician Danny “Big Black” Ray Orchestre Afrisa Intern. -

High Fashion, Lower Class of La Sape in Congo

Africa: History and Culture, 2019, 4(1) Copyright © 2019 by Academic Publishing House Researcher s.r.o. Published in the Slovak Republic Africa: History and Culture Has been issued since 2016. E-ISSN: 2500-3771 2019, 4(1): 4-11 DOI: 10.13187/ahc.2019.1.4 www.ejournal48.com Articles and Statements “Hey! Who is that Dandy?”: High Fashion, Lower Class of La Sape in Congo Shuan Lin a , * a National Changhua University of Education, Taiwan Abstract Vestments transmit a sense of identity, status, and occasion. The vested body thus provides an ideal medium for investigating changing identities at the intersection of consumption and social status. This paper examines the vested body in the la Sape movement in Congo, Central Africa, by applying the model of ‘conspicuous consumption’ put forward by Thorstein Veblen. In so doing, the model of ‘conspicuous consumption’ illuminates how la Sape is more than an appropriation of western fashion, but rather a medium by which fashion is invested as a site for identity transformation in order to distinguish itself from the rest of the society. The analysis focuses particularly the development of this appropriation of western clothes from the pre-colonial era to the 1970s with the intention of illustrating the proliferation of la Sape with the expanding popularity of Congolese music at its fullest magnitude, and the complex consumption on clothing. Keywords: Congo, Conspicuous Consumption, la Sape, Papa Wemba, Vested Body, Vestments. 1. Introduction “I saved up to buy these shoes. It took me almost two years. If I hadn’t bought this pair, I’d have bought a plot of land,” he said proudly, adding that it’s the designer logo that adds to his “dignity” and “self-esteem.” “I had to buy them,” he said. -

Rumba Under Fire

DUMITRESCU RUMBA UNDER FIRE THE ARTS OF SURVIVAL FROM WEST POINT TO DELHI EDITED BY IRINA DUMITRESCU RUMBA UNDER FIRE RUMBA UNDER FIRE RUMBA UNDER FIRE THE ARTS OF SURVIVAL FROM WEST POINT TO DELHI EDITED BY IRINA DUMITRESCU PUNCTUM BOOKS EARTH RUMBA UNDER FIRE: THE ARTS OF SURVIVAL FROM WEST POINT TO DELHI © 2016 Irina Dumitrescu http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ This work carries a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. First published in 2016 by punctum books Printed on Earth http://punctumbooks.com punctum books is an independent, open-access publisher dedicated to radically creative modes of intellectual inquiry and writing across a whimsical para-humantities assemblage. We solicit and pimp quixotic, sagely mad engagements with textual thought-bodies. We provide shelters for intellectual vagabonds. ISBN-13: 978-0692655832 ISBN-10: 0692655832 Cover and book design: Chris Piuma. Cover photo: Private Walter Koch of Ohio of the Sixth United States Army takes a break during torrential rain in northern New Guinea in 1944. Photo used with permission of the Aus- tralian War Memorial. -

Revisedphdwhole THING Whizz 1

McGuinness, Sara E. (2011) Grupo Lokito: a practice-based investigation into contemporary links between Congolese and Cuban popular music. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/14703 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. GRUPO LOKITO A practice-based investigation into contemporary links between Congolese and Cuban popular music Sara E. McGuinness Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2011 School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Identity Politics in Nairobi Matatu Folklore Mbugua Wa-Mungai

Identity Politics in Nairobi Matatu Folklore Mbugua Wa-Mungai To cite this version: Mbugua Wa-Mungai. Identity Politics in Nairobi Matatu Folklore. Philosophy. Department of Jewish and Comparative Folklore The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2003. English. tel-01259814 HAL Id: tel-01259814 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01259814 Submitted on 21 Jan 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Identity Politics in Nairobi Matatu Folklore A dissertation presented to the Senate of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, for the award of the degree degree of doctor of philosophy Mbugua wa-Mungai Department of Jewish and Comparative Folklore The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 11 1FRA 1111111 111 1111 111 IIIIII IF RA002891 Wow 3o1. March 2003 Declaration This dissertation is my original work and has not been submitted for any academic award, or other credit, in any other institution. The writing has been done under the supervision of Professor Gain. Hasan-Rokem, Department of Jewish and Comparative Folklore and Dr. Hagar Salmon. Departments of Jewish and Comparative Folklore and Middle Eastern and African Studies. Dedication To the MbuQua clan, my wife Wanibui, and our children Mun.gai and Njeri, in appreciation for the life that we share, for braving the lonely years and for keeping my place by the fireside as I went matatu-chasing.