Rumba Under Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 PETRE P. CARP 100 De Ani De La Moarte (Bibliografie Selectivă) (N. 29

PETRE P. CARP 100 de ani de la moarte (bibliografie selectivă) (n. 29 iunie 1837, Iași - d. 19 iunie 1919, Țibănești) I. OPERA 1. Volume Afacerea tramvaelor la Senat : după note stenografice / discursurile domnilor P. P. Carp şi Al. Marghiloman. - Bucureşti : Tipografia şi Stabilimentul de Arte Grafice George Ionescu, 1911. - 47 p. Auswartige Politik und Agrarreform / reden und zeitungsartikel von P. P. Carp; autorisierte Ubers. von Victor A. Beldiman und Erwin von Fehlmayr. - Bukarest : Socec, 1917. - 78 p. Discursuri : vol. 1 : 1868-1888 / P. P. Carp. - Bucureşti : Editura Librăriei Socec & Co. S. A., 1907. Discursuri parlamentare / P. P. Carp. - [București] : Tipografia Curţii Regale, [1895]. - 299 p. Discursuri parlamentare / P. P. Carp; ediţie îngrijită de Marcel Duţă; studiu introductiv de Ion Bulei. - Bucureşti : Grai şi suflet - Cultura naţională, 2000. - 630 p. (COTA: III 27418; 32(498)/C26) Exproprierea marei proprietăţi / P. P. Carp. - Bucureşti : Tipografia şi Stabilimentul de Arte Grafice G. Ionescu, 1914. Patru discursuri rostite în Senat / de Petre P. Carp. - Iaşi : Tipografia Naţională, 1878. - 30 p. Politica externă a României : cuvîntările rostite în discuţia răspunsului la Mesaj în şedinţele din 14, 15, 16 şi 17 decembrie 1915 ale Camerei Deputaţilor / de d-nii P. P. Carp şi C. Stere. - Iaşi : Editura Revistei Viaţa Românească, 1915. - 61 p. Procesul Maiorescu cu actele autentice / P. P. Carp, N. Mândrea, G. Mârzescu, I. Negruzzi, V. Pogor. - Iaşi : Imprimeria Adolf Bermann, 1865. - 23, LXVI p. România şi răsboiul european / P. P. Carp. - Bucureşti : Tipografia Dorneanu I., s.a. - 32 p. Tulburările de la 5 aprilie şi Legea maximului : două discursuri rostite în Cameră / de Al. -

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Nathan Oyori Ogechi aus Kenia Hamburg 2002 ii 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt Datum der Disputation: 15. November 2002 iii Acknowledgement I am indebted to many people for their support and encouragement. It is not possible to mention all by name. However, it would be remiss of me not to name some of them because their support was too conspicuous. I am bereft of words with which to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh for accepting to supervise my research and her selflessness that enabled me secure further funding at the expiry of my one-year scholarship. Her thoroughness and meticulous supervision kept me on toes. I am also indebted to Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt for reading my error-ridden draft. I appreciate the support I received from everybody at the Afrika-Abteilung, Universität Hamburg, namely Dr. Roland Kießling, Theda Schumann, Dr. Jutta Becher, Christiane Simon, Christine Pawlitzky and the institute librarian, Frau Carmen Geisenheyner. Professors Myers-Scotton, Kamwangamalu, Clyne and Auer generously sent me reading materials whenever I needed them. Thank you Dr. Irmi Hanak at Afrikanistik, Vienna, Ndugu Abdulatif Abdalla of Leipzig and Bi. Sauda Samson of Hamburg. I thank the DAAD for initially funding my stay in Deutschland. Professors Miehe and Khamis of Bayreuth must be thanked for their selfless support. I appreciate the kind support I received from the Akademisches Auslandsamt, University of Hamburg. -

Henri H. Stahl's Contribution to the Sociological Monographs of the Bucharest School of Sociology

UTOPIA CONSTRUCTIVĂ A MONOGRAFIEI HENRI H. STAHL’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE SOCIOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS OF THE BUCHAREST SCHOOL OF SOCIOLOGY ALINA JURAVLE* ABSTRACT This study is an attempt to shed light onto Henri H. Stahl’s contribution to the sociological monographs that were the core of the Bucharest School of Sociology’s activity. Stahl is presented as an active member of the School, bringing into it his own background and abilities, distinct or shared views, values and interests and then impacting it through his actions which, combined with other factors, distinctively change and shape its development. As such, the study is also not an attempt to summarize his theoretical developments and to compare and place them in rapport with those of other social scientists. The purpose of this study is to expose at least partially the degree to which the knowledge that Stahl generates and uses differs in shape and contents from that of Dimitrie Gusti, regarding the manner in which it is used in his course towards a certain role and status in the School, the manner in which his course in the School develops, and the manner in which his personal characteristics and options, group and organizational developments and the wider social context interact in order to shape published sociological knowledge. Keywords: Henri H. Stahl, sociological monographs, Bucharest School of Sociology, knowledge. THE SOCIOLOGICAL MONOGRAPH – THEORY, METHOD, PRINTED SCIENTIFIC RESULT The following study is an attempt to shed light onto Henri H. Stahl’s contribution to the sociological monographs that were the core of the Bucharest School of Sociology’s activity. -

Maria PAȘCALĂU,Moses Gaster Și Lazăr Șăineanu: Problema Dublei

MOSES GASTER ȘI LAZĂR ȘĂINEANU: PROBLEMA DUBLEI IDENTITĂȚI Maria PAȘCALĂU Universitatea de Vest din Timișoara [email protected] Moses Gaster and Lazăr Șăineanu: The Question of Double Identity In the 1880s, as a result of the acculturation process, a generation of elite Jewish intellectuals became active, who promoted the idea of Romanian Jewish identity and came to make significant contributions to Romanian science and culture. The present paper aims to study the question of double identity concerning the generation of Romania’s acculturated Jewish intellectuals in the late 19th century, by analyzing two representative cases: Moses Gaster, a moderate assimilationist with Jewish nationalist tendencies, and Lazăr Șăineanu, who came to adopt a radical form of assimilation by converting to Christianity. This research will be undertaken from an interdisciplinary approach that includes cultural, historical, and political perspectives. The question of double identity regarding the two Jewish intellectuals will be related to aspects of their biographical trajectory, with a focus on their personal and professional backgrounds, on the relationship with the Jewish community and religious life, on cultural and scientific concerns, as well as on integration issues. By following the personal and cultural destinies of the two Jewish intellectuals, this paper aims to emphasize the impact of their work on both Romanian and Jewish cultures and to reveal the main difficulties that the whole generation they represented had to face by assuming the Romanian Jewish identity: increase in anti-Semitism, hostile reactions coming from the cultural and political authorities, rejection of integration, the pressure of the Romanian culture with ethnic-national identity tendencies on their Jewish identity. -

India Architecture Guide 2017

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Zanskar Geologically, the Zanskar Range is part of the Tethys Himalaya, an approximately 100-km-wide synclinorium. Buddhism regained its influence Lungnak Valley over Zanskar in the 8th century when Tibet was also converted to this ***** Zanskar Desert ཟངས་དཀར་ religion. Between the 10th and 11th centuries, two Royal Houses were founded in Zanskar, and the monasteries of Karsha and Phugtal were built. Don't miss the Phugtal Monastery in south-east Zanskar. Zone 2: Punjab Built in 1577 as the holiest Gurdwara of Sikhism. The fifth Sikh Guru, Golden Temple Rd, Guru Arjan, designed the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) to be built in Atta Mandi, Katra the centre of this holy tank. The construction of Harmandir Sahib was intended to build a place of worship for men and women from all walks *** Golden Temple Guru Ram Das Ahluwalia, Amritsar, Punjab 143006, India of life and all religions to come and worship God equally. The four entrances (representing the four directions) to get into the Harmandir ਹਰਿਮੰਦਿ ਸਾਰਹਬ Sahib also symbolise the openness of the Sikhs towards all people and religions. Mon-Sun (3-22) Near Qila Built in 2011 as a museum of Sikhism, a monotheistic religion originated Anandgarh Sahib, in the Punjab region. Sikhism emphasizes simran (meditation on the Sri Dasmesh words of the Guru Granth Sahib), that can be expressed musically *** Virasat-e-Khalsa Moshe Safdie Academy Road through kirtan or internally through Nam Japo (repeat God's name) as ਰਿਿਾਸਤ-ਏ-ਖਾਲਸਾ a means to feel God's presence. -

20 De Scriitori TIPAR.Qxp

20 ROMANIAN WRITERS 20 ROMANIAN WRITERS Translations from the Romanian by Alistair Ian Blyth Artwork by Dragoş Tudor © ROMANIAN CULTURAL INSTITUTE CONTENT Gabriela Adameşteanu 6 Daniel Bănulescu 12 M. Blecher 18 Mircea Cărtărescu 22 Petru Cimpoeşu 28 Lena Constante 34 Gheorghe Crăciun 38 Filip Florian 42 Ioan Groşan 46 Florina Ilis 50 Mircea Ivănescu 56 Nicolae Manolescu 62 Ion Mureşan 68 Constantin Noica 74 Răzvan Petrescu 80 Andrei Pleşu 86 Ioan Es. Pop 92 N. Steinhardt 98 Stelian Tănase 102 Ion Vartic 108 Gabriela Adameşteanu Born 1942. Writer and translator. Editor-in-chief of the Bucureştiul cultural supplement of 22 magazine. Published volumes: The Even way of Every Day (1975), Give Yourself a Holiday (1979), Wasted Morning (1983) (French translation, Éditions Gallimard, 2005), Summer-Spring (1989), The Obsession of Politics (1995), The Two Romanias (2000), The Encounter (2004) Romanian Writers’ Union Prize for Debut, Romanian Academy Prize (1975), Romanian Writers’ Union Prize for Novel (1983), Hellman Hammet Prize, awarded by Human Rights Watch (2002), Ateneu literary review and Ziarul de Iaşi Prize for the novel The Encounter (2004) 6 7 The starched bonnet of Madame Ana moves over Oh, our stable, mediocre familial sentiments, of the tea table, then into the middle of the room, which it would seem you are not worthy, as long next to the tall-legged tables. On each of them she as you cannot prevent yourself from seeing the places a five-armed candelabra and, after hesitating one close to you! From seeing him and, on seeing “Wasted Morning … is one of the best novels to have been published in recent him, from falling into the sin of judging years: rich, even dense, profound, ‘true’ in the most minute of details, modern in its him! construction, and written with finesse. -

Memory, Justice and Moral Cleansing

SPRING 2017 | VOL.27 | N0.2 ACTON INSTITUTE'S INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RELIGION, ECONOMICS AND CULTURE Memory, justice and moral cleansing What are Freedom and the When our success transatlantic values? nation-state threatens our success EDITOR'S NOTE Sarah Stanley MANAGING EDITOR This spring issue of Religion & Liberty is, among other things, a reflection on the 100-year anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution and the horrors committed by Communist regimes. For the cover story, Religion & Liberty executive editor, John Couretas, interviews Mihail Neamţu, a leading conservative in Romania. They discuss the Russian Revolution and current protests against corruption going on in Romania. A similar topic appears in Rev. Anthony Perkins’ re- view of the 2017 film Bitter Harvest. This love story is set in the Ukraine during the Holodomor, a deadly famine imposed on Ukraine by Joseph Stalin’s Soviet regime in the 1930s. Perkins addresses the signifi- cance of the Holodomor in his critique of the new movie. Romanian Orthodox hermit INTERVIEW Nicolae Steinhardt was another victim of a 07 Memory, justice and moral cleansing Communist regime. During imprisonment Coming to grips with the Russian Revolution and its legacy in a Romanian gulag, he found faith and Interview with Romanian public intellectual Mihail Neamţu even happiness. A rare excerpt in English from his “Diary of Happiness” appears in this issue. You’ve probably noticed this issue of Religion & Liberty looks very different from previous ones. As part of a wider look at international issues, this magazine has been updated and expanded to include new sections focusing on the unique chal- lenges facing Canada, Europe and the Unit- ed States. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Gail Kligman Distinguished

CURRICULUM VITAE Gail Kligman Distinguished Professor Department of Sociology University of California Box 951551 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551 Tel.: 310-206-7277 (office) 310-206-9838 (department fax) [email protected] [email protected] Kligman @soc.ucla.edu [email protected] Place of birth: Philadelphia, PA Specializations Historical-Comparative Sociology, Political Sociology, Gender, Socialism and Postsocialism, International Migration, Trafficking, Eastern Europe, Ethnographic Methods. Education Ph.D. 1977 University of California, Berkeley (Sociology) M.A. 1973 University of California, Berkeley (Folklore) B.A. 1971 University of California, Berkeley (Sociology) Academic Positions Affiliated Professor, Promise Institute for Human Rights, UCLA Law, 2021- . Affiliated Professor, UCLA Bixby Program for Population and Reproductive Health, 2021--. Special Academic Advisor on International Research to the UCLA Vice-Chancellor for Research, 2019-2020. Associate Vice Provost, UCLA International Institute, 2015-2019. Affiliated Professor, Global Public Affairs, UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, 2015- . Director, UCLA Center for European and Eurasian Studies, 2005-2015. Distinguished Professor of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles, 2012- . Professor, Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles, 1995---. Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles, 1993- 1995 (on leave 1993-94). Ion Ratiu Visiting Chair of Romanian Studies, Department of -

The Life of the Romanian Theologian Antonie Plamadeala As a Runaway from the Secret Police and As a Political Prisoner in Communist Romania

The Life of the Romanian Theologian Antonie Plamadeala as a Runaway from the Secret Police and as a Political Prisoner in Communist Romania Cristina Plamadeala A Thesis in The Department of Theological Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Theological Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2015 © Cristina Plamadeala, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Cristina Plamadeala Entitled: The Life of the Romanian Theologian Antonie Plamadeala as a Runaway from the Secret Police and as a Political Prisoner in Communist Romania and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Theological Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: __________________________________Chair Chair’s name __________________________________Examiner Examiner’s name __________________________________Examiner Examiner’s name __________________________________Supervisor Supervisor’s name Approved by_______________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______2015 _______________________________________________________ Dean of Faculty ii ABSTRACT The Life of the Romanian Theologian Antonie Plamadeala as a Runaway from the Secret Police and as a Political Prisoner in Communist Romania Cristina Plamadeala The present work discusses the life of the Romanian theologian Antonie Plamadeala (1926-2005) in the1940s-1950s. More specifically, it tells the story of his refuge from Bessarabia to Romania, of his run from Romania’s secret police (Securitate) and of his years of incarceration as a political prisoner for alleged ties to the Legionary Movement, known for its Fascist, paramilitary and anti-Semitic activity and rhetoric. -

Introduction

INTRODUctION Burrel, Spaç, Qafë-Bari, Ruzyně, Pankrác, Mírov, Leopoldov, Valdice, Jáchymov, Bytíz u Přibrami, Białołęka, Aiud, Gherla, Jilava, Piteşti, Recsk, Lovech, Belene, Idrizovo, Goli otok. These are names that mean little or nothing to many. But to East Europeans from Central Europe to the farthest reaches of the Balkans, they form an indelible part of their collective memory as the darkest page in the forty-five-year history of communism in the region. They are the names of detention centers, prison camps, and forced labor camps that corrupted the landscape of Eastern Europe from the end of World War II to the collapse of communism in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Although less familiar than the Soviet gulag made famous through the writings of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and undeniably Soviet in inspiration, they were no less brutal and dehumanizing.1 They became a living hell for a huge number of human beings from every walk of life, especially intellectuals, artists, and students whose only crime in many in- stances was a repugnance for the repressive Communist system that demanded conformity and brooked no opposition. Resistance to the imposition of Communist rule throughout Eastern Europe manifested itself almost from the very beginning and grew into mass, and some- times violent, eruptions of protest, among them the Poznań riots in Poland in October 1956, the Hungarian Revolution later that same year, the Prague Spring that led to the Soviet and Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, the rise of Solidarity in Poland in the early 1980s—the reverberations from which were ultimately felt throughout all of Eastern Europe—and the bloody upheaval that ended the reign of Nicolae Ceauşescu in Romania in December 1989. -

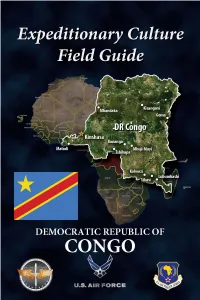

ECFG-DRC-2020R.Pdf

ECFG About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally t complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The he fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. Democratic Republicof The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), focusing on unique cultural features of the DRC’s society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN © Siegfried Modola). the For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact Congo AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2015 Studio Magazine Board of Trustees This Issue of Studio Is Underwritten, Editor-In-Chief Raymond J

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2015 Studio magazine Board of Trustees This issue of Studio is underwritten, Editor-in-Chief Raymond J. McGuire, Chairman in part, with support from Elizabeth Gwinn Carol Sutton Lewis, Vice-Chair Rodney M. Miller, Treasurer Creative Director The Studio Museum in Harlem is sup- Thelma Golden Dr. Anita Blanchard ported, in part, with public funds provided Jacqueline L. Bradley Managing Editor by the following government agencies and Valentino D. Carlotti Dana Liss elected representatives: Kathryn C. Chenault Joan S. Davidson Copy Editor The New York City Department of Cultural Gordon J. Davis, Esq. Samir S. Patel Aairs; New York State Council on the Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Arts, a state agency; National Endowment Design Sandra Grymes for the Arts; the New York City Council; Pentagram Arthur J. Humphrey Jr. and the Manhattan Borough President. George L. Knox Printing Nancy L. Lane Allied Printing Services The Studio Museum in Harlem is deeply Dr. Michael L. Lomax grateful to the following institutional do- Original Design Concept Bernard I. Lumpkin nors for their leadership support: 2X4, Inc. Dr. Amelia Ogunlesi Ann G. Tenenbaum Studio is published two times a year Bloomberg Philanthropies John T. Thompson by The Studio Museum in Harlem, Booth Ferris Foundation Reginald Van Lee 144 W. 125th St., New York, NY 10027. Ed Bradley Family Foundation The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Hon. Bill de Blasio, ex-oicio Copyright ©2015 Studio magazine. Charitable Trust Hon. Tom Finkelpearl, ex-oicio Ford Foundation All rights, including translation into other The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation languages, are reserved by the publisher.