Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Nathan Oyori Ogechi aus Kenia Hamburg 2002 ii 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt Datum der Disputation: 15. November 2002 iii Acknowledgement I am indebted to many people for their support and encouragement. It is not possible to mention all by name. However, it would be remiss of me not to name some of them because their support was too conspicuous. I am bereft of words with which to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh for accepting to supervise my research and her selflessness that enabled me secure further funding at the expiry of my one-year scholarship. Her thoroughness and meticulous supervision kept me on toes. I am also indebted to Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt for reading my error-ridden draft. I appreciate the support I received from everybody at the Afrika-Abteilung, Universität Hamburg, namely Dr. Roland Kießling, Theda Schumann, Dr. Jutta Becher, Christiane Simon, Christine Pawlitzky and the institute librarian, Frau Carmen Geisenheyner. Professors Myers-Scotton, Kamwangamalu, Clyne and Auer generously sent me reading materials whenever I needed them. Thank you Dr. Irmi Hanak at Afrikanistik, Vienna, Ndugu Abdulatif Abdalla of Leipzig and Bi. Sauda Samson of Hamburg. I thank the DAAD for initially funding my stay in Deutschland. Professors Miehe and Khamis of Bayreuth must be thanked for their selfless support. I appreciate the kind support I received from the Akademisches Auslandsamt, University of Hamburg. -

Identity, Nationalism, and Resistance in African Popular Music

Instructor: Jeffrey Callen, Ph.D., Adjunct Faculty, Department of Performing Arts, University of San Francisco SYLLABUS ETHNOMUSICOLOGY 98T: IDENTITY, NATIONALISM AND RESISTANCE IN AFRICAN POPULAR MUSIC How are significant cultural changes reflected in popular music? How does popular music express the aspirations of musicians and fans? Can popular music help you create a different sense of who you are? Course Statement: The goal of this course is to encourage you to think critically about popular music. Our focus will be on how popular music in Africa expresses people’s hopes and aspirations, and sense of who they are. Through six case studies, we will examine the role popular music plays in the formation of national and transnational identities in Africa, and in mobilizing cultural and political resistance. We will look at a wide variety of African musical styles from Congolese rumba of the 1950s to hip-hop in a variety of African countries today. Readings: There is one required book for this course: Music is the Weapon of the Future by Frank Tenaille. Additional readings are posted on the Blackboard site for this class. Readings are to be done prior to the week in which they are discussed Listenings: Listenings (posted on Blackboard) are to be done prior to the week in which they are discussed. If entire albums are assigned for listening, listen to as much as you have time for. The Course Blog: The course blog will be an important part of this course. On it you will post your reactions to the class listenings and readings. It also lists internet resources that will prove helpful in finding supplemental information on class subjects and in preparing your final research project. -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

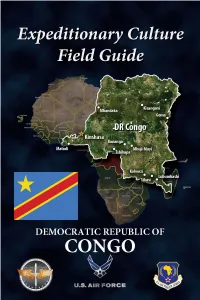

ECFG-DRC-2020R.Pdf

ECFG About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally t complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The he fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. Democratic Republicof The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), focusing on unique cultural features of the DRC’s society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN © Siegfried Modola). the For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact Congo AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2015 Studio Magazine Board of Trustees This Issue of Studio Is Underwritten, Editor-In-Chief Raymond J

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2015 Studio magazine Board of Trustees This issue of Studio is underwritten, Editor-in-Chief Raymond J. McGuire, Chairman in part, with support from Elizabeth Gwinn Carol Sutton Lewis, Vice-Chair Rodney M. Miller, Treasurer Creative Director The Studio Museum in Harlem is sup- Thelma Golden Dr. Anita Blanchard ported, in part, with public funds provided Jacqueline L. Bradley Managing Editor by the following government agencies and Valentino D. Carlotti Dana Liss elected representatives: Kathryn C. Chenault Joan S. Davidson Copy Editor The New York City Department of Cultural Gordon J. Davis, Esq. Samir S. Patel Aairs; New York State Council on the Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Arts, a state agency; National Endowment Design Sandra Grymes for the Arts; the New York City Council; Pentagram Arthur J. Humphrey Jr. and the Manhattan Borough President. George L. Knox Printing Nancy L. Lane Allied Printing Services The Studio Museum in Harlem is deeply Dr. Michael L. Lomax grateful to the following institutional do- Original Design Concept Bernard I. Lumpkin nors for their leadership support: 2X4, Inc. Dr. Amelia Ogunlesi Ann G. Tenenbaum Studio is published two times a year Bloomberg Philanthropies John T. Thompson by The Studio Museum in Harlem, Booth Ferris Foundation Reginald Van Lee 144 W. 125th St., New York, NY 10027. Ed Bradley Family Foundation The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Hon. Bill de Blasio, ex-oicio Copyright ©2015 Studio magazine. Charitable Trust Hon. Tom Finkelpearl, ex-oicio Ford Foundation All rights, including translation into other The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation languages, are reserved by the publisher. -

Culture and Customs of Kenya

Culture and Customs of Kenya NEAL SOBANIA GREENWOOD PRESS Culture and Customs of Kenya Cities and towns of Kenya. Culture and Customs of Kenya 4 NEAL SOBANIA Culture and Customs of Africa Toyin Falola, Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sobania, N. W. Culture and customs of Kenya / Neal Sobania. p. cm.––(Culture and customs of Africa, ISSN 1530–8367) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–31486–1 (alk. paper) 1. Ethnology––Kenya. 2. Kenya––Social life and customs. I. Title. II. Series. GN659.K4 .S63 2003 305.8´0096762––dc21 2002035219 British Library Cataloging in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2003 by Neal Sobania All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2002035219 ISBN: 0–313–31486–1 ISSN: 1530–8367 First published in 2003 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 For Liz Contents Series Foreword ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Chronology xvii 1 Introduction 1 2 Religion and Worldview 33 3 Literature, Film, and Media 61 4 Art, Architecture, and Housing 85 5 Cuisine and Traditional Dress 113 6 Gender Roles, Marriage, and Family 135 7 Social Customs and Lifestyle 159 8 Music and Dance 187 Glossary 211 Bibliographic Essay 217 Index 227 Series Foreword AFRICA is a vast continent, the second largest, after Asia. -

African Studies

FILMS, VIDEOS & DVDS FOR African Studies The Future Of Mud: A Tale of Houses and Lives in Djenne A Film by Susan Vogel Presented by the Musée National du Mali This constructed documentary blends In interviews, information with narrative to show family members the cycle of mud building and the lives of masons talk about the in Djenne, a UNESCO World Heritage city in Mali. town of Djenne, its buildings, and THE FUTURE OF MUD focuses on the mason their desires for Komusa Tenaepo, who hopes that his son will the future, as do succeed him. The film shows a day in the life of a distinguished the mason and Amadou, his young helper from Koranic master, a poor family near Timbuktu, as Komusa decides and a staff whether to allow his son to leave for schooling member of the government office charged with in the capital. preserving the architecture of Djenne. The film reveals the interdependence between The film ends with thousands of participants at the masons, buildings, and lives lived in them. It exam- annual replastering of Djenne’s beloved mosque, ines the tenuous survival of the inherited learning an age-old event, which, for the first time, has been of masons, and the hard work that sustain this specially staged in hopes of attracting tourists. style of architecture. It shows life in Djenne’s mud buildings: courtyards, a blacksmiths’ workshop, a 2007 RAI International Festival of Ethnographic Film modern white vinyl sitting room, the construction site, and Friday prayers at the great mosque. 58 minutes | color | 2007 Sale/DVD: $390 | Order #AF7-01 First Run/Icarus Films | 1 Living Memory Malick Sidibé: A Film by Susan Vogel Portrait of the Artist as a Portraitist Produced by Susan Vogel, Samuel Sidibé, Eric Engles & the Musée National du Mali A Film by Susan Vogel The film is constructed in six sketches, focusing on This short but sweet film looks at the work of the “Brilliant!.. -

África: Revista Do Centro De Estudos Africanos

África: Revista do Centro de Estudos Africanos. USP, S. Paulo, 22-23: 111-119, 1999/2000/2001. THE GLOBALIZATION OF THE URBAN MUSIC OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO Kazadi wa MUKUNA * ABSTRACT: The term “globalization” has recently become a catchword in most languages. In the field of music, globalization begets the concept of “world music”. As a new concept in music, globalization presents a challenge to scholars and layman as to the scope of its definition. In this paper I assert that regardless of its accepted definition and concept, “world music” is becoming a reality as a product of the globalization process. As a hybrid product, “world music” is feeding on music cultures of the world. As with its community, and its culture, the semantic field of its language is also at present being defined. This assertion is sustained by a myriad of sound recordings born out of experimental collabo- ration by musicians. the urban music of the Democratic Republic of Congo has contrib- uted and continues to contribute to the evolution of the hybrid product in the attainment of its new identity. Keywords: Ethnomusicology; globalization; Popular Music of DRC; World music Although it has recently become a catchword, “globalization” is an open- ended process that implies different levels of unification. It is a reality that began emerging in recent decades in economic and political arenas, specifically in refer- ence to the creation of a world market and the promotion of multinational indus- tries. However, a closer look at the semantics of the term also brings to mind that globalization is a process which has occurred since the dawn of time, consciously or otherwise, through various forms of human activities. -

Downloaded4.0 License

Journal of World Literature 6 (2021) 216–244 brill.com/jwl Congolese Literature as Part of Planetary Literature Silvia Riva | orcid: 0000-0002-0100-0569 Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy [email protected] Abstract Historically and economically, the Congo has been considered one of the most interna- tionalized states of Africa. The idea that African cultural plurality was minimized dur- ing the colonial era has to be reconsidered because textual negotiations and exchanges (cosmopolitan and vernacular, written and oral) have been frequent during and after colonization, mostly in urban areas. Through multilingual examples, this paper aims to question the co-construction of linguistic and literary pluralism in Congo and to advo- cate for the necessity of a transdisciplinary and collaborative approach, to understand the common life of African vernacular and cosmopolitan languages. I show that world literature models based on Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of negotiation between center and periphery thus have to be replaced by a concept of multilingual global history. Finally, I propose the notion of “planetary literature” as a new way of understanding the inter- connection between literatures taking care of the world. Keywords restitution – post-scriptural orality – planetary literature – multilingualism – Third Landscape 1 Recast, Return, and the Opening Up to the World Let me start by recalling an essay dating back to the early 1990s by the philoso- pher V.Y. Mudimbe. In relation to contemporary African art, he introduced the notion of reprendre (literally, “to retake”) to mean both the act of taking up an interrupted tradition, not out of a desire for purity, which would testify only to the imaginations of dead ancestors, but in a way © silvia riva, 2021 | doi:10.1163/24056480-00602006 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the cc by-ncDownloaded4.0 license. -

High Fashion, Lower Class of La Sape in Congo

Africa: History and Culture, 2019, 4(1) Copyright © 2019 by Academic Publishing House Researcher s.r.o. Published in the Slovak Republic Africa: History and Culture Has been issued since 2016. E-ISSN: 2500-3771 2019, 4(1): 4-11 DOI: 10.13187/ahc.2019.1.4 www.ejournal48.com Articles and Statements “Hey! Who is that Dandy?”: High Fashion, Lower Class of La Sape in Congo Shuan Lin a , * a National Changhua University of Education, Taiwan Abstract Vestments transmit a sense of identity, status, and occasion. The vested body thus provides an ideal medium for investigating changing identities at the intersection of consumption and social status. This paper examines the vested body in the la Sape movement in Congo, Central Africa, by applying the model of ‘conspicuous consumption’ put forward by Thorstein Veblen. In so doing, the model of ‘conspicuous consumption’ illuminates how la Sape is more than an appropriation of western fashion, but rather a medium by which fashion is invested as a site for identity transformation in order to distinguish itself from the rest of the society. The analysis focuses particularly the development of this appropriation of western clothes from the pre-colonial era to the 1970s with the intention of illustrating the proliferation of la Sape with the expanding popularity of Congolese music at its fullest magnitude, and the complex consumption on clothing. Keywords: Congo, Conspicuous Consumption, la Sape, Papa Wemba, Vested Body, Vestments. 1. Introduction “I saved up to buy these shoes. It took me almost two years. If I hadn’t bought this pair, I’d have bought a plot of land,” he said proudly, adding that it’s the designer logo that adds to his “dignity” and “self-esteem.” “I had to buy them,” he said. -

Rumba Under Fire

DUMITRESCU RUMBA UNDER FIRE THE ARTS OF SURVIVAL FROM WEST POINT TO DELHI EDITED BY IRINA DUMITRESCU RUMBA UNDER FIRE RUMBA UNDER FIRE RUMBA UNDER FIRE THE ARTS OF SURVIVAL FROM WEST POINT TO DELHI EDITED BY IRINA DUMITRESCU PUNCTUM BOOKS EARTH RUMBA UNDER FIRE: THE ARTS OF SURVIVAL FROM WEST POINT TO DELHI © 2016 Irina Dumitrescu http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ This work carries a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. First published in 2016 by punctum books Printed on Earth http://punctumbooks.com punctum books is an independent, open-access publisher dedicated to radically creative modes of intellectual inquiry and writing across a whimsical para-humantities assemblage. We solicit and pimp quixotic, sagely mad engagements with textual thought-bodies. We provide shelters for intellectual vagabonds. ISBN-13: 978-0692655832 ISBN-10: 0692655832 Cover and book design: Chris Piuma. Cover photo: Private Walter Koch of Ohio of the Sixth United States Army takes a break during torrential rain in northern New Guinea in 1944. Photo used with permission of the Aus- tralian War Memorial. -

Download File

Mbalax: Cosmopolitanism in Senegalese Urban Popular Music Timothy Roark Mangin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Timothy Roark Mangin All rights reserved ABSTRACT Mbalax: Cosmopolitanism in Senegalese Urban Popular Music Timothy Roark Mangin This dissertation is an ethnographic and historical examination of Senegalese modern identity and cosmopolitanism through urban dance music. My central argument is that local popular culture thrives not in spite of transnational influences and processes, but as a result of a Senegalese cosmopolitanism that has long valued the borrowing and integration of foreign ideas, cultural practices, and material culture into local lifeways. My research focuses on the articulation of cosmopolitanism through mbalax, an urban dance music distinct to Senegal and valued by musicians and fans for its ability to shape, produce, re-produce, and articulate overlapping ideas of their ethnic, racial, generational, gendered, religious, and national identities. Specifically, I concentrate on the practice of black, Muslim, and Wolof identities that Senegalese urban dance music articulates most consistently. The majority of my fieldwork was carried out in the nightclubs and neighborhoods in Dakar, the capital city. I performed with different mbalax groups and witnessed how the practices of Wolofness, blackness, and Sufism layered and intersected to articulate a modern Senegalese identity, or Senegaleseness. This ethnographic work was complimented by research in recording studios, television studios, radio stations, and research institutions throughout Senegal. The dissertation begins with an historical inquiry into the foundations of Senegalese cosmopolitanism from precolonial Senegambia and the spread of Wolof hegemony, to colonial Dakar and the rise of a distinctive urban Senegalese identity that set the proximate conditions for the postcolonial cultural policy of Négritude and mbalax.