High Fashion, Lower Class of La Sape in Congo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng

Trilingual Codeswitching in Kenya – Evidence from Ekegusii, Kiswahili, English and Sheng Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Nathan Oyori Ogechi aus Kenia Hamburg 2002 ii 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt Datum der Disputation: 15. November 2002 iii Acknowledgement I am indebted to many people for their support and encouragement. It is not possible to mention all by name. However, it would be remiss of me not to name some of them because their support was too conspicuous. I am bereft of words with which to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Mechthild Reh for accepting to supervise my research and her selflessness that enabled me secure further funding at the expiry of my one-year scholarship. Her thoroughness and meticulous supervision kept me on toes. I am also indebted to Prof. Dr. Ludwig Gerhardt for reading my error-ridden draft. I appreciate the support I received from everybody at the Afrika-Abteilung, Universität Hamburg, namely Dr. Roland Kießling, Theda Schumann, Dr. Jutta Becher, Christiane Simon, Christine Pawlitzky and the institute librarian, Frau Carmen Geisenheyner. Professors Myers-Scotton, Kamwangamalu, Clyne and Auer generously sent me reading materials whenever I needed them. Thank you Dr. Irmi Hanak at Afrikanistik, Vienna, Ndugu Abdulatif Abdalla of Leipzig and Bi. Sauda Samson of Hamburg. I thank the DAAD for initially funding my stay in Deutschland. Professors Miehe and Khamis of Bayreuth must be thanked for their selfless support. I appreciate the kind support I received from the Akademisches Auslandsamt, University of Hamburg. -

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:07 p.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Article abstract Volume 21, Number 2, 2011 This essay offers broad reflection on some of the challenges faced by African composers of art music. The specific point of departure is the publication of a URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar new anthology, Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Ghanaian pianist and scholar William Chapman Nyaho and published in 2009 by Oxford University Press. The anthology exemplifies a diverse range of See table of contents creative achievement in a genre that is less often associated with Africa than urban ‘popular’ music or ‘traditional’ music of pre-colonial origins. Noting the virtues of musical knowledge gained through individual composition rather than ethnography, the article first comments on the significance of the Publisher(s) encounters of Steve Reich and György Ligeti with various African repertories. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Then, turning directly to selected pieces from the anthology, attention is given to the multiple heritage of the African composer and how this affects his or her choices of pitch, rhythm and phrase structure. Excerpts from works by Nketia, ISSN Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi and Osman serve as illustration. 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Agawu, K. (2011). The Challenge of African Art Music. Circuit, 21(2), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Halifu Osumare, the Hiplife in Ghana: West Africa Indigenization of Hip-Hop, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 219 Pp., $85.00 (Hardcover)

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), Book Review 1501–1504 1932–8036/2013BKR0009 Halifu Osumare, The Hiplife in Ghana: West Africa Indigenization of Hip-Hop, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 219 pp., $85.00 (hardcover). Reviewed by Angela Anima-Korang Southern Illinois University Carbondale Ghana’s music industry can be described as a thriving one, much like its film industry. The West African sovereign state is well on its way to becoming a force to reckon with on the international music market. With such contemporary rap artists as Sarkodie, Fuse ODG (Azonto), Reggie Rockstone, R2Bs, and Edem in its fold, Ghana’s music is transcending borders and penetrating international markets. Historically, Ghana’s varying ethnic groups, as well as its interaction with countries on the continent, greatly influences the genres of music that the country has created over the years. Traditionally, Ghana’s music is geographically categorized by the types of musical instruments used: Music originating from the North uses stringed instruments and high-pitched voices; and music emanating from the Coast features drums and relatively low-pitched voice intermissions. Up until the 1990s, “highlife” was the most popular form of music in Ghana, borrowing from jazz, swing, rock, soukous, and mostly music to which the colonizers had listened. Highlife switched from the traditional form with drums to a music genre characterized by the electric guitar. “Burger-highlife” then erupted as a form of highlife generated by artists who had settled out of Ghana (primarily in Germany), but who still felt connected to the motherland through music, such as Ben Brako, George Darko, and Pat Thomas. -

Explore African Immigrant Musical Traditions with Your Students Recommended for Grade Levels 5 and Up

Explore African Immigrant Musical Traditions with Your Students Recommended for Grade Levels 5 and up Teacher Preparation / Goals African immigrant musical traditions are as rich and varied as the many languages and cultures of Africa. There are many different reasons for their formation; to explore new influences, to reshape older practices, or to maintain important traditions from the homeland. In these reading and activities students will learn about the African immigrant musical traditions found in the Washington, D.C. area. Special programs held after school and during the weekend and summer have been initiated to teach children more about their culture through the medium of music and dance. In the African immigrant community, music and dance groups immerse the students in the culture of their ancestors’ homeland. Some of these groups have been here for many years and are an important part of the community. Many African-born parents value these programs because they fear that their American-born children may be losing their heritage. In preparation for the lesson read the attached articles, "African Immigrant Music and Dance in Washington, D.C." and "Nile Ethiopian Ensemble: A Profile of An African Immigrant Music and Dance Group." See what you can find out about the musical traditions to be found in your area, and not just those performed by African immigrants, but by others as well. For example, when you start looking, you may find a Korean group or a group from the Czech Republic. If possible, visit a performance of a music or dance group and talk to the teachers or directors of the group. -

Designfreebies Indesign Brochure Template

Page1 www.karibumusic.org Page3 Bagamoyo Until the middle of the 18th century, Bagamoyo was a small, rather insignificant trading center. Trade items were fish, salt and gum among other things. Most of the population consisted of fishermen and farmers. 19th century: The arrival of the Arabs. Bagamoyo became a central point for the East African slave trade In 1868 Muslims presented the “Fathers of the Holy Ghost” with land to build a mission north of Bagamoyo - the first mission in East Africa. 19th century: A starting point for the expeditions of Livingstone and others. 1874: The body of Livingstone is laid-in-state in Bagamoyo. 1880: Bagamoyo is a multi-cultural town with about 1,000 inhabitants. 1888: Bagamoyo becomes the capital of German-East Africa. Welcome Note KARIBU MUSIC FESTIVAL 2014 Content Festival Overview ............................... Page 7 Karibu Cultural Promotions................ Page 8 Technical partner ............................... Page 9 Partners............................................... Page 10 Festival Artists .................................... Page 11 - 31 Music Workshops & Seminars ........... Page 32 Performance Schedule.......................... Page 36 Festival Map..........................................Page 37 7 Festival Overview aribu Music Festival is an annual, Three-days International Music Festival created by Karibu KCultural Promotions, a nonprofit making organization and the Legendary Music Entertainment & Promotion of Dar es Salaam Tanzania. This is the second edition of the Karibu Music Festival to be held at Bagamoyo, the College of Arts and Culture (TASUBA) and on Mwanakalenge grounds. Karibu Festival is composed of various genres of art such as music, dance and cultural exposure; where by artists from different parts of the world are invited to share the stage with the local artists of Tanzania. -

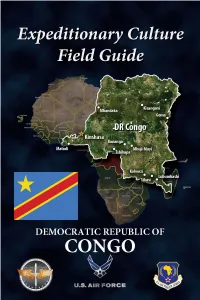

ECFG-DRC-2020R.Pdf

ECFG About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally t complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The he fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. Democratic Republicof The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), focusing on unique cultural features of the DRC’s society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN © Siegfried Modola). the For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact Congo AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. -

“Indépendance Cha Cha”: African Pop Music Since the Independence Era, In: Africa Spectrum, 45, 3, 131-146

Africa Spectrum Dorsch, Hauke (2010), “Indépendance Cha Cha”: African Pop Music since the Independence Era, in: Africa Spectrum, 45, 3, 131-146. ISSN: 1868-6869 (online), ISSN: 0002-0397 (print) The online version of this and the other articles can be found at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Published by GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Institute of African Affairs in co-operation with the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation Uppsala and Hamburg University Press. Africa Spectrum is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To subscribe to the print edition: <[email protected]> For an e-mail alert please register at: <www.africa-spectrum.org> Africa Spectrum is part of the GIGA Journal Family which includes: Africa Spectrum • Journal of Current Chinese Affairs • Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs • Journal of Politics in Latin America • <www.giga-journal-family.org> Africa Spectrum 3/2010: 131-146 “Indépendance Cha Cha”: African Pop Music since the Independence Era Hauke Dorsch Abstract: Investigating why Latin American music came to be the sound- track of the independence era, this contribution offers an overview of musi- cal developments and cultural politics in certain sub-Saharan African coun- tries since the 1960s. Focusing first on how the governments of newly inde- pendent African states used musical styles and musicians to support their nation-building projects, the article then looks at musicians’ more recent perspectives on the independence era. Manuscript received 17 November 2010; 21 February 2011 Keywords: Africa, music, socio-cultural change Hauke Dorsch teaches cultural anthropology at Johannes Gutenberg Uni- versity in Mainz, Germany, where he also serves as the director of the Afri- can Music Archive. -

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2015 Studio Magazine Board of Trustees This Issue of Studio Is Underwritten, Editor-In-Chief Raymond J

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2015 Studio magazine Board of Trustees This issue of Studio is underwritten, Editor-in-Chief Raymond J. McGuire, Chairman in part, with support from Elizabeth Gwinn Carol Sutton Lewis, Vice-Chair Rodney M. Miller, Treasurer Creative Director The Studio Museum in Harlem is sup- Thelma Golden Dr. Anita Blanchard ported, in part, with public funds provided Jacqueline L. Bradley Managing Editor by the following government agencies and Valentino D. Carlotti Dana Liss elected representatives: Kathryn C. Chenault Joan S. Davidson Copy Editor The New York City Department of Cultural Gordon J. Davis, Esq. Samir S. Patel Aairs; New York State Council on the Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Arts, a state agency; National Endowment Design Sandra Grymes for the Arts; the New York City Council; Pentagram Arthur J. Humphrey Jr. and the Manhattan Borough President. George L. Knox Printing Nancy L. Lane Allied Printing Services The Studio Museum in Harlem is deeply Dr. Michael L. Lomax grateful to the following institutional do- Original Design Concept Bernard I. Lumpkin nors for their leadership support: 2X4, Inc. Dr. Amelia Ogunlesi Ann G. Tenenbaum Studio is published two times a year Bloomberg Philanthropies John T. Thompson by The Studio Museum in Harlem, Booth Ferris Foundation Reginald Van Lee 144 W. 125th St., New York, NY 10027. Ed Bradley Family Foundation The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Hon. Bill de Blasio, ex-oicio Copyright ©2015 Studio magazine. Charitable Trust Hon. Tom Finkelpearl, ex-oicio Ford Foundation All rights, including translation into other The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation languages, are reserved by the publisher. -

Culture and Customs of Kenya

Culture and Customs of Kenya NEAL SOBANIA GREENWOOD PRESS Culture and Customs of Kenya Cities and towns of Kenya. Culture and Customs of Kenya 4 NEAL SOBANIA Culture and Customs of Africa Toyin Falola, Series Editor GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sobania, N. W. Culture and customs of Kenya / Neal Sobania. p. cm.––(Culture and customs of Africa, ISSN 1530–8367) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–31486–1 (alk. paper) 1. Ethnology––Kenya. 2. Kenya––Social life and customs. I. Title. II. Series. GN659.K4 .S63 2003 305.8´0096762––dc21 2002035219 British Library Cataloging in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2003 by Neal Sobania All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2002035219 ISBN: 0–313–31486–1 ISSN: 1530–8367 First published in 2003 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 For Liz Contents Series Foreword ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Chronology xvii 1 Introduction 1 2 Religion and Worldview 33 3 Literature, Film, and Media 61 4 Art, Architecture, and Housing 85 5 Cuisine and Traditional Dress 113 6 Gender Roles, Marriage, and Family 135 7 Social Customs and Lifestyle 159 8 Music and Dance 187 Glossary 211 Bibliographic Essay 217 Index 227 Series Foreword AFRICA is a vast continent, the second largest, after Asia. -

African Popular Music Ensemble Tuesdays (7:20 PM-9:10 PM) at the School of Music Dr

1 FALL 2021 MUN 1xxx - section TBA World Music Ensemble – African Popular Music Ensemble Tuesdays (7:20 PM-9:10 PM) at the School of Music Dr. Sarah Politz, [email protected] Office: Yon Hall 435 Office hours: TBA Credits: 1.0 credit hours The African Popular Music Ensemble will specialize in the popular music of the African continent, with a special focus on Afrobeat, highlife, soukous, African jazz, and the brass band traditions of Africa and the diaspora. Together we will listen to, perform, and arrange music from the works of Fela Kuti (Nigeria), Salif Keita (Mali), Hugh Masekela, Abdullah Ibrahim, Miriam Makeba (South Africa), Mulatu Astatke (Ethiopia), and the Gangbe Brass Band of Benin. Instrumentation will vary based on personnel each semester, and will typically include a rhythm section, horn section, and vocal soloists. The ensemble will also draw on the participation of faculty performers, as well as guest artists specializing in African popular music from the community and beyond. These collaborations will contribute to the diversity of musical and cultural experiences related to Africa that are available to students throughout the semester. Course Objectives The African Popular Music Ensemble is dedicated to learning African culture through musical performance. After completion of this course, students will be able to perform in a variety of African popular music styles on their instrument. These skills will be developed through a combination of listening to recordings, developing skills in listening and blending within the ensemble, and individual study and practice outside of rehearsals. Students who wish to develop their skills in improvisation will have many opportunities to do so. -

Journals.Openedition.Org/Etudesafricaines/159 DOI : 10.4000/Etudesafricaines.159 ISSN : 1777-5353

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenEdition Cahiers d’études africaines 168 | 2002 Musiques du monde Réflexions sur un hymne continental La musique africaine dans le monde* Bob W. White Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/159 DOI : 10.4000/etudesafricaines.159 ISSN : 1777-5353 Éditeur Éditions de l’EHESS Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 janvier 2002 Pagination : 633-644 ISBN : 978-2-7132-1778-4 ISSN : 0008-0055 Référence électronique Bob W. White, « Réflexions sur un hymne continental », Cahiers d’études africaines [En ligne], 168 | 2002, mis en ligne le 27 juin 2005, consulté le 02 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ etudesafricaines/159 ; DOI : 10.4000/etudesafricaines.159 © Cahiers d’Études africaines Bob W. White Réflexions sur un hymne continental La musique africaine dans le monde* En dépit des appréhensions quant à son caractère imprévisible, la mondiali- sation commence à sembler drôlement prévisible. D’un côté, on applaudit la concrétisation du rêve néo-libéral de la déréglementation des marchés, de la libre circulation des capitaux et de l’accès illimité à une main-d’œuvre bon marché. De l’autre, on dénonce l’élargissement du fossé qui sépare les riches et les pauvres, les changements climatiques imminents et les menaces de disparition qui pèsent sur diverses espèces biologiques et culturelles. Cette inquiétude, comme l’observe Arjun Appadurai (2000) dans un ouvrage récent qui s’intitule tout simplement « Globalization », a servi les ambitions des industries du savoir en Occident, notamment la recherche et l’édition universitaires, sans pour autant les délivrer du mal du provincialisme. -

The Commodification of Culture in the Postcolonial Anglophone

Consuming the Other: The Commodification of Culture in the Postcolonial Anglophone World by José Sebastián Terneus A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: J. Edward Mallot, Chair Lee Bebout Gregory Castle ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 ABSTRACT This project examines different modes of cultural production from the postcolonial Anglophone world to identify how marginal populations have either been subjugated or empowered by various forms of consumerism. Four case studies specifically follow the flow of products, resources, and labor either in the colonies or London. In doing so, these investigations reveal how neocolonial systems both radiate from old imperial centers and occupy postcolonial countries. Using this method corroborates contemporary postcolonial theory positing that modern “Empire” is now amorphous and stateless rather than constrained to the metropole and colony. The temporal progression of each chapter traces how commodification and resource exploitation has evolved from colonial to contemporary periods. Each section of this study consequently considers geography and time to show how consumer culture grew via imperialism, yet also supported and challenged the progression of colonial conquest. Accordingly, as empire and consumerism have transformed alongside each other, so too have the tools that marginal groups use to fight against economic and cultural subjugation. Novels remain as one traditional format – and consumer product – that can resist the effects of colonization. Other contemporary postcolonial artists, however, use different forms of media to subvert or challenge modes of neocolonial oppression. Texts such as screenplays, low-budget films, memoirs, fashion subcultures, music videos, and advertisements illuminate how postcolonial groups represent themselves.