Species Listing PROPOSAL Form: Listing Endangered, Threatened, and Special Concern Species in Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

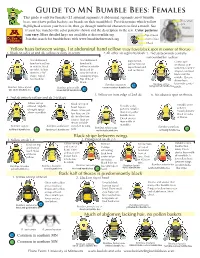

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble Three small bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns ® can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Bee Front of face Squad Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee C patch. two-spotted bumble bee C brown-belted bumble bee C 5. Yellow on front edge of 2nd ab 6. No obvious spot on thorax. 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Meet the Rare, Threatened and Endangered Insect Pollinators Of

NDSU EXTENSION E1977 Meet the Rare, Threatened and Endangered Jeremy Hemberger Johanna James-Heinze Insect Pollinators of North Dakota David Lowenstein, Consumer Horticulture Extension Educator, Michigan State University Nathaniel Walton, Consumer Horticulture Extension Educator, Michigan State University Patrick Beauzay, Integrated Pest Management Coordinator and Research Specialist, NDSU Veronica Calles-Torrez, Post-doctoral Scientist, NDSU Gerald Fauske, Insect Collection Manager and Research Specialist, NDSU David L. Cuthrell, Esther McGinnis, Extension Horticulturist, NDSU Michigan State University Janet Knodel, Extension Entomologist, NDSU Erik Runquist, Minnesota Zoo Why are some pollinators in decline? Rusty Patched Bumble Bee (Bombus affinis) and Nectar, pollen and habitat are three major requirements of Yellow-banded Bumble Bee (B. terricola) pollinators. When habitats (for example, natural areas) are lost to Gardeners frequently see and recognize bumble bees throughout agriculture, residential homes or commercial spaces, some insect the growing season, but some species have declined rapidly in the pollinators can undergo a rapid decline. Specialized pollinators are past few decades. Two declining bumble bee species are native to more susceptible to habitat or food losses because they often are the northern U.S. from the Dakotas eastward. dependent on a few specific host plants in a specialized habitat. Both feed on specific plants, compared with other bumble bees, Environmental contamination from using herbicides that which feed on a wider host plant list. In addition to habitat loss, prevent flowers from blooming or insecticides that kill pollinators their decline may be caused by a natural disadvantage in tolerating immediately or through time degrades otherwise suitable habitats. pathogens spread from commercially reared bumble bees. -

Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan

Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan Prepared By: Logan M. Rowe, David L. Cuthrell, and Helen D. Enander Michigan Natural Features Inventory Michigan State University Extension P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901 Prepared For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division 12/17/2019 MNFI Report No. 2019-33 Suggested Citation: Rowe, L. M., D. L. Cuthrell., H. D. Enander. 2019. Assessing Bumble Bee Diversity, Distribution, and Status for the Michigan Wildlife Action Plan. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2019- 33, Lansing, USA. Copyright 2019 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. MSU Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover: Bombus terricola taken by D. L. Cuthrell Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ iii Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Methods ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 Museum Searches .................................................................................................................................... -

Western Bumble Bee,Bombus Occidentalis

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Western Bumble Bee Bombus occidentalis occidentalis subspecies - Bombus occidentalis occidentalis mckayi subspecies - Bombus occidentalis mckayi in Canada occidentalis subspecies - THREATENED mckayi subspecies - SPECIAL CONCERN 2014 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2014. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Western Bumble Bee Bombus occidentalis, occidentalis subspecies (Bombus occidentalis occidentalis) and the mckayi subspecies (Bombus occidentalis mckayi) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xii + 52 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Sheila Colla, Michael Otterstatter, Cory Sheffield and Leif Richardson for writing the status report on the Western Bumble Bee, Bombus occidentalis, in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Jennifer Heron, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Arthropods Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Bourdon de l'Ouest (Bombus occidentalis) de la sous-espèce occidentalis (Bombus occidentalis occidentalis) et la sous-espèce mckayi (Bombus occidentalis mckayi) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Western Bumble Bee — Cover photograph by David Inouye, Western Bumble Bee worker robbing an Ipomopsis flower. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014. -

Interspecific Geographic Distribution and Variation of the Pathogens

Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 109 (2012) 209–216 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Invertebrate Pathology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jip Interspecific geographic distribution and variation of the pathogens Nosema bombi and Crithidia species in United States bumble bee populations Nils Cordes a, Wei-Fone Huang b, James P. Strange c, Sydney A. Cameron d, Terry L. Griswold c, ⇑ Jeffrey D. Lozier e, Leellen F. Solter b, a University of Bielefeld, Evolutionary Biology, Morgenbreede 45, 33615 Bielefeld, Germany b Illinois Natural History Survey, Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois, 1816 S. Oak St., Champaign, IL 61820, United States c USDA-ARS Pollinating Insects Research Unit, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5310, United States d Department of Entomology and Institute for Genomic Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, United States e Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487, United States article info abstract Article history: Several bumble bee (Bombus) species in North America have undergone range reductions and rapid Received 4 September 2011 declines in relative abundance. Pathogens have been suggested as causal factors, however, baseline data Accepted 10 November 2011 on pathogen distributions in a large number of bumble bee species have not been available to test this Available online 18 November 2011 hypothesis. In a nationwide survey of the US, nearly 10,000 specimens of 36 bumble bee species collected at 284 sites were evaluated for the presence and prevalence of two known Bombus pathogens, the micros- Keywords: poridium Nosema bombi and trypanosomes in the genus Crithidia. Prevalence of Crithidia was 610% for all Bombus species host species examined but was recorded from 21% of surveyed sites. -

Report for the Yellow Banded Bumble Bee (Bombus Terricola) Version 1.1

Species Status Assessment (SSA) Report for the Yellow Banded Bumble Bee (Bombus terricola) Version 1.1 Kent McFarland October 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northeast Region Hadley, Massachusetts 1 Acknowledgements Gratitude and many thanks to the individuals who responded to our request for data and information on the yellow banded bumble bee, including: Nancy Adamson, U.S. Department of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS); Lynda Andrews, U.S. Forest Service (USFS); Sarah Backsen, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS); Charles Bartlett, University of Delaware; Janet Beardall, Environment Canada; Bruce Bennett, Environment Yukon, Yukon Conservation Data Centre; Andrea Benville, Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre; Charlene Bessken USFWS; Lincoln Best, York University; Silas Bossert, Cornell University; Owen Boyle, Wisconsin DNR; Jodi Bush, USFWS; Ron Butler, University of Maine; Syd Cannings, Yukon Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada; Susan Carpenter, University of Wisconsin; Paul Castelli, USFWS; Sheila Colla, York University; Bruce Connery, National Park Service (NPS); Claudia Copley, Royal Museum British Columbia; Dave Cuthrell, Michigan Natural Features Inventory; Theresa Davidson, Mark Twain National Forest; Jason Davis, Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife; Sam Droege, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS); Daniel Eklund, USFS; Elaine Evans, University of Minnesota; Mark Ferguson, Vermont Fish and Wildlife; Chris Friesen, Manitoba Conservation Data Centre; Lawrence Gall, -

Suckley's Cuckoo Bumblebee Listing Petition

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST SUCKLEY’S CUCKOO BUMBLE BEE (Bombus suckleyi) UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT AND CONCURRENTLY DESIGNATE CRITICAL HABITAT Suckley’s cuckoo bumble bee Hadel Go, AMNH CC BY-NC 3.0 US CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY April 23, 2020 NOTICE OF PETITION David Bernhardt, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Margaret Everson, Principal Deputy Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1840 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Robyn Thorson, Regional Director Region 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 911 NE 11th Ave. Portland, OR 97232-4181 [email protected] Anna Munoz, Assistant Regional Director Region 6 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 650 Lakewood, CO 80228 [email protected] Paul Souza, Regional Director Region 8 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2800 Cottage Way, Suite W2606 Sacramento, California 95825 [email protected] ii Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b); Section 553(e) of the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e); and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity hereby petitions the Secretary of the Interior, through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS,” “Service”), to protect Suckley’s cuckoo bumble bee (Bombus suckleyi) under the ESA. -

Status Report and Assessment of Western

SPECIES STATUS REPORT Western Bumble Bee, Yellow-banded Bumble Bee, and Gypsy Cuckoo Bumble Bee (Bombus occidentalis, Bombus terricola, Bombus bohemicus) Bourdon de l’ouest, Bourdon terricole, Psithyre bohémien (French) Ineedzit (Teetl’it and Gwichyah Gwich’in) Kw’ıahnǫ dekwoo (Dogrib) Tł’ıstthó Tł’ıstthóghe (Chipewyan) Tth’ıhnǫ detthoı (South Slavey) April 2019 DATA DEFICIENT – Western bumble bee NOT AT RISK – Yellow-banded bumble bee DATA DEFICIENT – Gypsy cuckoo bumble bee Status of Western Bumble Bee, Yellow-banded Bumble Bee, and Gypsy Cuckoo Bumble Bee in the NWT Species at Risk Committee status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of species suspected of being at risk in the Northwest Territories (NWT). Suggested citation: Species at Risk Committee. 2019. Species Status Report for Western Bumble Bee, Yellow-banded Bumble Bee, and Gypsy Cuckoo Bumble Bee (Bombus occidentalis, Bombus terricola, Bombus bohemicus) in the Northwest Territories. Species at Risk Committee, Yellowknife, NT. © Government of the Northwest Territories on behalf of the Species at Risk Committee ISBN: 978-0-7708-0264-6/0-7708-0264-8 Production note: The drafts of this report were prepared by Dr. Christopher M. Ernst under contract with the Government of the Northwest Territories, and edited by Claire Singer. For additional copies contact: Species at Risk Secretariat c/o SC6, Department of Environment and Natural Resources P.O. Box 1320 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 Tel.: (855) 783-4301 (toll free) Fax.: (867) 873-0293 E-mail: [email protected] www.nwtspeciesatrisk.ca ABOUT THE SPECIES AT RISK COMMITTEE The Species at Risk Committee was established under the Species at Risk (NWT) Act. -

Guide to Bumble Bees of the Western United States

Bumble Bees of the Western United States By Jonathan Koch James Strange A product of the U.S. Forest Service and the Pollinator Partnership Paul Williams with funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Executive Editor Larry Stritch, Ph.D., USDA Forest Service Cover: Bombus huntii foraging. Photo Leah Lewis Executive and Managing Editor Laurie Davies Adams, The Pollinator Partnership Graphic Design and Art Direction Marguerite Meyer Administration Jennifer Tsang, The Pollinator Partnership IT Production Support Elizabeth Sellers, USGS Alphabetical Quick Reference to Species B. appositus .............110 B. frigidus ..................46 B. rufocinctus ............86 B. balteatus ................22 B. griseocollis ............90 B. sitkensis ................38 B. bifarius ..................78 B. huntii ....................66 B. suckleyi ...............134 B. californicus ..........114 B. insularis ...............126 B. sylvicola .................70 B. caliginosus .............26 B. melanopygus .........62 B. ternarius ................54 B. centralis ................34 B. mixtus ...................58 B. terricola ...............106 B. crotchii ..................82 B. morrisoni ...............94 B. vagans ...................50 B. fernaldae .............130 B. nevadensis .............18 B. vandykei ................30 B. fervidus................118 B. occidentalis .........102 B. vosnesenskii ..........74 B. flavifrons ...............42 B. pensylvanicus subsp. sonorus ....122 B. franklini .................98 2 Bumble Bees of the -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Hickory Nut Gorge Green Salamander (Aneides caryaensis) Photo by Austin Patton 2014 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Animal Species of North Carolina 2020 Compiled by Judith Ratcliffe, Zoologist North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. The list is published periodically, generally every two years. -

A Field Guide to Bumble Bees of the Northwest Territories

A Field Guide to Bumble Bees of the Northwest Territories This identification guide includes all species of bumble bees known to be present in the Northwest Territories. ©Recommended 2017 Government citation: of the Northwest Territories Environment and Natural Resources. 2017. A Field Guide to Bumble Bees of the Northwest Territories. Environment and Natural Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories. Yellowknife, NT. 64pp. An Identification Guide:Details Bumble on bumble Bees bee of North species America and diagrams of species colour ranges were crafted from the book and reproduced here, with permission from Princeton University Press. All errors remain our own. Museum specimen location data was generously shared by Leif Richardson, University of Vermont. Photos from bugguide.net were used with permission. Other photos have been donated through NWT Species Facebook group (www.facebook.com/groups/NWTSpecies) and used with permission. Thanks to Cory Sheffield for species identification. Front cover: Bomus perplexus – Fort Smith © Heidi Beilschmidt Selzler Table of Contents The Importance of Bumble Bees .............................................4 Bumble Bee Anatomy .............................................................5 The Bumble Bee Body ....................................................................5 Mimicry ..........................................................................................6 The Bumble Bee Colony ..........................................................8 Life Cycle and Stage .......................................................................9 -

The Decline and Conservation Status of North American Bumble Bees

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2011 The Decline and Conservation Status of North American Bumble Bees Jonathan B. Koch Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Koch, Jonathan B., "The Decline and Conservation Status of North American Bumble Bees" (2011). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1015. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1015 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DECLINE AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF NORTH AMERICAN BUMBLE BEES by Jonathan Berenguer Koch A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Biology Approved: ________________________ ________________________ Dr. James P. Pitts Dr. James P. Strange Major Professor Committee Member ________________________ ________________________ Dr. David N. Koons Dr. Byron R. Burnham Committee Member Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2011 ii Copyright © Jonathan Berenguer Koch 2011 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT The decline and conservation status of North American bumble bees by Jonathan Berenguer Koch, Master of Science Utah State University, 2011 Major Professor: Dr. James P. Pitts Department: Biology Several reports of North American bumble bee (Bombus Latreille) decline have been documented across the continent, but no study has fully assessed the geographic scope of decline. In this study I discuss the importance of Natural History Collections (NHC) in estimating historic bumble bee distributions and abundances, as well as in informing current surveys.