Conserving Bumble Bees Guidelines for Creating and Managing Habitat for America's Declining Pollinators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thresholds of Response in Nest Thermoregulation by Worker Bumble Bees, Bombus Bifarius Nearcticus (Hymenoptera: Apidae)

Ethology 107, 387Ð399 (2001) Ó 2001 Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin ISSN 0179±1613 Animal Behavior Area, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle and Department of Psychology, University of Puget Sound, Tacoma Thresholds of Response in Nest Thermoregulation by Worker Bumble Bees, Bombus bifarius nearcticus (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Sean O'Donnell & Robin L. Foster O'Donnell, S. & Foster, R. L. 2001: Thresholds of response in nest thermoregulation by worker bumble bees, Bombus bifarius nearcticus (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Ethology 107, 387Ð399. Abstract Regulation of nest temperature is important to the ®tness of eusocial insect colonies. To maintain appropriate conditions for the developing brood, workers must exhibit thermoregulatory responses to ambient temperature. Because nest- mate workers dier in task performance, thermoregulatory behavior provides an opportunity to test threshold of response models for the regulation of division of labor. We found that worker bumble bees (Bombus bifarius nearcticus) responded to changes in ambient temperature by altering their rates of performing two tasks ± wing fanning and brood cell incubation. At the colony level, the rate of incubating decreased, and the rate of fanning increased, with increasing temperature. Changes in the number of workers performing these tasks were more important to the colony response than changes in workers' task perform- ance rates. At the individual level, workers' lifetime rates of incubation and fanning were positively correlated, and most individuals did not specialize exclusively on either of these temperature-sensitive tasks. However, workers diered in the maximum temperature at which they incubated and in the minimum temperature at which they fanned. More individuals fanned at high and incubated at low temperatures. -

Anthidium Manicatum, an Invasive Bee, Excludes a Native Bumble Bee, Bombus Impatiens, from floral Resources

Biol Invasions https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1889-7 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) ORIGINAL PAPER Anthidium manicatum, an invasive bee, excludes a native bumble bee, Bombus impatiens, from floral resources Kelsey K. Graham . Katherine Eaton . Isabel Obrien . Philip T. Starks Received: 15 April 2018 / Accepted: 21 November 2018 Ó Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 Abstract Anthidium manicatum is an invasive pol- response to A. manicatum presence. We found that B. linator reaching widespread distribution in North impatiens avoided foraging near A. manicatum in both America. Male A. manicatum aggressively defend years; but despite this resource exclusion, we found no floral territories, attacking heterospecific pollinators. evidence of fitness consequences for B. impatiens. Female A. manicatum are generalists, visiting many of These results suggest A. manicatum pose as significant the same plants as native pollinators. Because of A. resource competitors, but that B. impatiens are likely manicatum’s rapid range expansion, the territorial able to compensate for this resource loss by finding behavior of males, and the potential for female A. available resources elsewhere. manicatum to be significant resource competitors, invasive A. manicatum have been prioritized as a Keywords Exotic species Á Resource competition Á species of interest for impact assessment. But despite Interspecific competition Á Foraging behavior Á concerns, there have been no empirical studies inves- Pollination tigating the impact of A. manicatum on North Amer- ican pollinators. Therefore, across a two-year study, we monitored foraging behavior and fitness of the common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens) in Introduction With increasing movement of goods and people Electronic supplementary material The online version of around the world, introduction of exotic species is this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1889-7) con- increasing at an unprecedented rate (Ricciardi et al. -

The Maryland Entomologist

THE MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGIST Insect and related-arthropod studies in the Mid-Atlantic region Volume 7, Number 2 September 2018 September 2018 The Maryland Entomologist Volume 7, Number 2 MARYLAND ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY www.mdentsoc.org Executive Committee: President Frederick Paras Vice President Philip J. Kean Secretary Janet A. Lydon Treasurer Edgar A. Cohen, Jr. Historian (vacant) Journal Editor Eugene J. Scarpulla E-newsletter Editors Aditi Dubey The Maryland Entomological Society (MES) was founded in November 1971, to promote the science of entomology in all its sub-disciplines; to provide a common meeting venue for professional and amateur entomologists residing in Maryland, the District of Columbia, and nearby areas; to issue a periodical and other publications dealing with entomology; and to facilitate the exchange of ideas and information through its meetings and publications. The MES was incorporated in April 1982 and is a 501(c)(3) non-profit, scientific organization. The MES logo features an illustration of Euphydryas phaëton (Drury) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae), the Baltimore Checkerspot, with its generic name above and its specific epithet below (both in capital letters), all on a pale green field; all these are within a yellow ring double-bordered by red, bearing the message “● Maryland Entomological Society ● 1971 ●”. All of this is positioned above the Shield of the State of Maryland. In 1973, the Baltimore Checkerspot was named the official insect of the State of Maryland through the efforts of many MES members. Membership in the MES is open to all persons interested in the study of entomology. All members receive the annual journal, The Maryland Entomologist, and the monthly e-newsletter, Phaëton. -

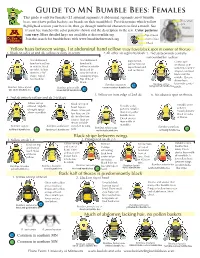

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble Three small bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns ® can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Bee Front of face Squad Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee C patch. two-spotted bumble bee C brown-belted bumble bee C 5. Yellow on front edge of 2nd ab 6. No obvious spot on thorax. 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Bumble Bee Abundance in New York City Community Gardens: Implications for Urban Agriculture

Matteson and Langellotto: URBAN BUMBLE BEE ABUNDANCE Cities and the Environment 2009 Volume 2, Issue 1 Article 5 Bumble Bee Abundance in New York City Community Gardens: Implications for Urban Agriculture Kevin C. Matteson and Gail A. Langellotto Abstract A variety of crops are grown in New York City community gardens. Although the production of many crops benefits from pollination by bees, little is known about bee abundance in urban community gardens or which crops are specifically dependent on bee pollination. In 2005, we compiled a list of crop plants grown within 19 community gardens in New York City and classified these plants according to their dependence on bee pollination. In addition, using mark-recapture methods, we estimated the abundance of a potentially important pollinator within New York City urban gardens, the common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens). This species is currently recognized as a valuable commercial pollinator of greenhouse crops. However, wild populations of B. impatiens are abundant throughout its range, including in New York City community gardens, where it is the most abundant native bee species present and where it has been observed visiting a variety of crop flowers. We conservatively counted 25 species of crop plants in 19 surveyed gardens. The literature suggests that 92% of these crops are dependent, to some degree, on bee pollination in order to set fruit or seed. Bombus impatiens workers were observed visiting flowers of 78% of these pollination-dependent crops. Estimates of the number of B. impatiens workers visiting individual gardens during the study period ranged from 3 to 15 bees per 100 m2 of total garden area and 6 to 29 bees per 100 m2 of garden floral area. -

Bumble Bees of CT-Females

Guide to CT Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow Three small eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Front of face Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee patch. two-spotted bumble bee brown-belted bumble bee 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black 5. No obvious spot on thorax. Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Global Trends in Bumble Bee Health

EN65CH11_Cameron ARjats.cls December 18, 2019 20:52 Annual Review of Entomology Global Trends in Bumble Bee Health Sydney A. Cameron1,∗ and Ben M. Sadd2 1Department of Entomology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA; email: [email protected] 2School of Biological Sciences, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois 61790, USA; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020. 65:209–32 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on Bombus, pollinator, status, decline, conservation, neonicotinoids, pathogens October 14, 2019 The Annual Review of Entomology is online at Abstract ento.annualreviews.org Bumble bees (Bombus) are unusually important pollinators, with approx- https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-011118- imately 260 wild species native to all biogeographic regions except sub- 111847 Saharan Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. As they are vitally important in Copyright © 2020 by Annual Reviews. natural ecosystems and to agricultural food production globally, the increase Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020.65:209-232. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org All rights reserved in reports of declining distribution and abundance over the past decade ∗ Corresponding author has led to an explosion of interest in bumble bee population decline. We Access provided by University of Illinois - Urbana Champaign on 02/11/20. For personal use only. summarize data on the threat status of wild bumble bee species across bio- geographic regions, underscoring regions lacking assessment data. Focusing on data-rich studies, we also synthesize recent research on potential causes of population declines. There is evidence that habitat loss, changing climate, pathogen transmission, invasion of nonnative species, and pesticides, oper- ating individually and in combination, negatively impact bumble bee health, and that effects may depend on species and locality. -

Bumble Bees in Montana

Bumble Bees in Montana by Amelia C. Dolan, Middle School Specialist at Athlos Academies, Boise, ID and former MSU Graduate Student; Casey M. Delphia, Research Scientist, Departments of Ecology and LRES; and Lauren M. Kerzicnik, Insect Diagnostician and Assistant IPM Specialist Bumble bees are important native pollinators in wildlands and agricultural systems. Creating habitat to support bumble bees in yards and gardens can MontGuide be easy and is a great way to get involved in native bee conservation. MT201611AG New 7/16 BUMBLE BEES ARE IMPORTANT NATIVE Bumble bees are one group of bees that are able to pollinators in wildlands and agricultural systems. They “buzz pollinate,” which is important for certain types are easily recognized by their large size and colorful, hairy of plants such as blueberries and tomatoes. Within bodies. Queens are active in the spring and workers can the flowers of these types of plants, pollen is held in be seen throughout the summer into early fall. Creating small tube-like anthers (i.e. poricidal anthers), and is habitat to support bumble bees in yards and gardens can not released unless the anthers are vibrated. Bumble be easy and is a great way to get involved in native bee bees buzz pollinate by landing on the flower, grabbing conservation. the anthers with their jaws (i.e. mandibles), and then Bumble bees are in the family Apidae (includes honey quickly vibrating their flight muscles. The vibration bees, bumble bees, carpenter bees, cuckoo bees, sunflower effect is similar to an electric toothbrush and the pollen bees, and digger bees) and the is released. -

Portland Field Guide

FIELD GUIDE FRITZ HAEG’S ANIMAL ESTATES REGIONAL MODEL HOMES 5.0 PORTLAND, OREGON 5 . N 0 O P G O RE RTLAND, O ANIMAL ESTATES 5.0 PORTLAND, OREGON DOUGLAS F. COOLEY MEMORIAL ART GALLERY REED COLLEGE 26 AUGUST–5 OCTOBER 2008 FRITZ HAEG 04 INTRODUCTION 10 IN LIVABLE CITIES IS FRITZ HAEG PRESERVATION OF THE WILD MIKE HOUCK 06 BUILD A BETTER SNAG! 14 SNAGS AND LOGS STEPHANIE SNYDER CHARLOTTE CORKRAN ANIMAL CLIENTS 18 CLIENT 5.1 34 CLIENT 5.5 VAUX’S SWIFT NORTHWESTERN GARTER SNAKE CHAETURA VAUXI THAMNOPHIS SIRTALIS TETRATAENIA CONTENTS BOB SALLINGER TIERRA CURRY 2 2 CLIENT 5.2 38 CLIENT 5.6 WHITE-BREASTED NUTHATCH ORANGE-RUMPED BUMBLEBEE SITTA CAROLINENSIS BOMBUS MELANOPYGUS CHARLOTTE CORKRAN CHRISTOPHER MARSHALL 26 CLIENT 5.3 42 CLIENT 5.7 OLIVE-SIDED FLYCATCHER SNAIL-EATING GROUND BEETLE CONTOPUS COOPERI SCAPHINOTUS ANGULATUS CHARLOTTE CORKRAN CHRISTOPHER MARSHALL 30 CLIENT 5.4 SILVER-HAIRED BAT LASIONYCTERIS NOCTIVAGANS CHARLOTTE CORKRAN 46 FIELD NOTES 48 CREDITS CLIENT 5.1 VAUX’S SWIFT CHAETURA VAUXI The ongoing Animal Estates lished between the man-made and the wild. initiative creates dwellings for Animals and their habitats are woven back into our cities, strip malls, garages, offi ce parks, animals that have been displaced freeways, backyards, parking lots, and neigh- by humans. Each edition of borhoods. Animal Estates intends to provide a the project is accompanied by provocative twenty-fi rst-century model for the some combination of events, human-animal relationship that is more intimate, visible, and thoughtful. workshops, exhibitions, videos, printed materials, and a temporary PORTLAND headquarters presenting an ever- In the gallery, the temporary Animal Estates expanding urban wildlife archive. -

Response of Pollinators to the Tradeoff Between Resource Acquisition And

Oikos 000: 001–010, 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.19910.x © 2011 The Authors. Oikos © 2011 Nordic Society Oikos Subject Editor: Koos Biesmierer. Accepted 25 July 2011 0 Response of pollinators to the tradeoff between resource 53 acquisition and predator avoidance 55 5 Ana L. Llandres, Eva De Mas and Miguel A. Rodríguez-Gironés 60 A. L. Llandres ([email protected]), E. De Mas and M. A. Rodríguez-Gironés, Dept of Functional and Evolutionary Ecology, Estación Experimental de Zonas Áridas (CSIC), Carretera de Sacramento, s/n, ES-04120, La Cañada de San Urbano, Almería, Spain. 10 65 Although the behaviour of animals facing the conflicting demands of increasing foraging success and decreasing predation risk has been studied in many taxa, the response of pollinators to variations in both factors has only been studied in isola- tion. We compared visit rates of two pollinator species, hoverflies and honeybees, to 40 Chrysanthemum segetum patches 15 in which we manipulated predation risk (patches with and without crab spiders) and nectar availability (rich and poor patches) using a full factorial design. Pollinators responded differently to the tradeoff between maximising intake rate and minimising predation risk: honeybees preferred rich safe patches and avoided poor risky patches while the number of hov- 70 erflies was highest at poor risky patches. Because honeybees were more susceptible to predation than hoverflies, our results suggest that, in the presence of competition for resources, less susceptible pollinators concentrate their foraging effort on 20 riskier resources, where competition is less severe. Crab spiders had a negative effect on the rate at which inflorescences were visited by honeybees. -

Bombus Vancouverensis Cresson, 1878 Common Name: Two Form Bumble Bee ELCODE: IIHYM24070 Taxonomic Serial No.: 714787

Alaska Natural Heritage Program Conservation Status Report Bombus vancouverensis Cresson, 1878 Common Name: Two Form Bumble Bee ELCODE: IIHYM24070 Taxonomic Serial No.: 714787 Synonyms: Pyrobombus bifarius Cresson, 1878; Bombus bifarius Cresson, 1878 Taxonomy Notes: Williams et al. (2014) report that DNA barcode data indicate this species has two lineages. However, the Barcode of Life Data System (BOLD) has all samples of this species (n = 163) grouped in a single BIN (BOLD:AAB4830). Ghisbain et al. (2020) concluded that B. bifarius sensu stricto does not occur in Alaska, and therefore all specimens are now B. vancouverensis and Sikes & Rykken (2020) concurred. Report last updated – November 2, 2020 Conservation Status G5 S3 Occurrences, Range Number of Occurrences: 20, number of museum records: 3,646 (Canadian National Collection, Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Alaska Museum Insect Collection, University of Alberta Museums, Koch et al. 2015). AK Range Extent: Bombus vancouverensis occurrences 359,987 km2; 4-km2 grid cells: 19. Found on the Seward Peninsula, and in Interior Alaska, the Matanuska Valley and the Copper River Basin. Also in Haines and Alaska-Canada Border at Stewart. North American Distribution: Alaska and south west Yukon Territory to British Columbia to the Pacific Northwest. In the Great Basin, Rocky Mountains, Arizona, New Mexico, Sierra Mountains and California Coast. Trends Trends are based on museum voucher collections of all Bombus species. Short-term trends are focus the past two decades (2000’s and 2010s), whereas long-term trends are based on all years. Data originate from museum voucher collections only and are summarized by decade. White bars indicate the number of voucher collections for the species. -

The Conservation Status of Bumble Bees of Canada, the USA, and Mexico

The Conservation Status of Bumble Bees of Canada, the USA, and Mexico Scott Hoffman Black, Rich Hatfield, Sarina Jepsen, Sheila Colla and Rémy Vandame Photo: Clay Bolt Importance of Bumble Bees There are 57 bumble bee species in Canada, US and Mexico. Hunt’s bumble bee; Bombus huntii , Photo: Clay Bolt Importance of Bumble Bees Important pollinator of many crops. Bombus sandersoni , Sanderson’s bumble bee Photo: Clay Bolt Importance of Bumble Bees Keystone pollinator in ecosystems. Yelllowheaded bumble bee, Bombus flavifrons Photo: Clay Bolt Bumble Bee Extinction Risk Assessment Network of 75+ bumble bee experts & specialists worldwide Goal: global bumble bee extinction risk assessment using consistent criteria Bumble Bee Extinction Risk Assessment IUCN Red List Criteria for Evaluating Extinction Risk • Used a database of 250,000+ specimen records (created from multiple data providers and compiled by Leif Richardson for Bumble Bees of North America) • Evaluate changes between recent (2002-2012) and historic (pre-2002): • Range (Extent of Occurrence) • Relative abundance • Persistence (50 km x 50 km grid cell occupancy) Sources: Hatfield et al. 2015 Bumble Bee Extinction Risk Assessment IUCN Red List Criteria for Evaluating Extinction Risk • Analyses informed application of Red List Categories; BBSG members provided review • This method was then adapted applied to South American and Mesoamerican bumble bees. Sources: Hatfield et al. 2015 Bumble Bee Extinction Risk Assessment Trilateral Region 6 4 5 28% of bumble bees Critically Endangered in Canada, the Endangered United States, and 7 Vulnerable Mexico are in an IUCN Threatened Near Threatened Category Least Concern 3 Data Deficient 32 Sources: Hatfield et al.