Anthidium Manicatum, an Invasive Bee, Excludes a Native Bumble Bee, Bombus Impatiens, from floral Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisconsin Bee Identification Guide

WisconsinWisconsin BeeBee IdentificationIdentification GuideGuide Developed by Patrick Liesch, Christy Stewart, and Christine Wen Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) The honey bee is perhaps our best-known pollinator. Honey bees are not native to North America and were brought over with early settlers. Honey bees are mid-sized bees (~ ½ inch long) and have brownish bodies with bands of pale hairs on the abdomen. Honey bees are unique with their social behavior, living together year-round as a colony consisting of thousands of individuals. Honey bees forage on a wide variety of plants and their colonies can be useful in agricultural settings for their pollination services. Honey bees are our only bee that produces honey, which they use as a food source for the colony during the winter months. In many cases, the honey bees you encounter may be from a local beekeeper’s hive. Occasionally, wild honey bee colonies can become established in cavities in hollow trees and similar settings. Photo by Christy Stewart Bumble bees (Bombus sp.) Bumble bees are some of our most recognizable bees. They are amongst our largest bees and can be close to 1 inch long, although many species are between ½ inch and ¾ inch long. There are ~20 species of bumble bees in Wisconsin and most have a robust, fuzzy appearance. Bumble bees tend to be very hairy and have black bodies with patches of yellow or orange depending on the species. Bumble bees are a type of social bee Bombus rufocinctus and live in small colonies consisting of dozens to a few hundred workers. Photo by Christy Stewart Their nests tend to be constructed in preexisting underground cavities, such as former chipmunk or rabbit burrows. -

LIFE 4 Pollinators Bees of the Mediterranean Hairs Are Used to Gather the Pollen Grains

NO OR FEW HAIR FEW OR NO HAIRY ANDRENID A may be present. be may E COLITIDAE E D I GU D IEL F morphogenus more than one class per category category per class one than more morphogenus COLITIDAE n each each n I classes. several propose we categories, protection under the common agricultural policy. agricultural common the under protection or each of these these of each or F colour. tegument and hairs strategy, the pollinators initiative and biodiversity biodiversity and initiative pollinators the strategy, MEGACHILIDAE he traits you need to observe at first are size, size, are first at observe to need you traits he T legislation, including amongst others the biodiversity biodiversity the others amongst including legislation, HALICTIDAE morphogenera defined by few traits. few by defined morphogenera U policy and and policy U E of range a to contribute wil project he T regroup them in few big groups of species called called species of groups big few in them regroup the remaining high-value pollinator habitats. pollinator high-value remaining the MEGACHILIDAE ees species are not easy to identify, but we we but identify, to easy not are species ees B and ensure sustainable management and restoration of of restoration and management sustainable ensure and the level of individual species individual of level the to address the main drivers behind pollinator decline decline pollinator behind drivers main the address to recognised within 15 morpho-groups and not at at not and morpho-groups 15 within recognised obstacles to proper planning of successful programmes programmes successful of planning proper to obstacles APIDAE morphological traits only, allows the bees to be be to bees the allows only, traits morphological his knowledge gap is one of the main main the of one is gap knowledge his T diversity. -

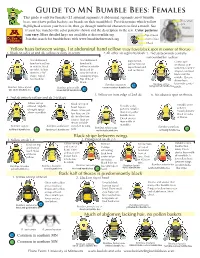

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble Three small bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns ® can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Bee Front of face Squad Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee C patch. two-spotted bumble bee C brown-belted bumble bee C 5. Yellow on front edge of 2nd ab 6. No obvious spot on thorax. 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Bumble Bee Abundance in New York City Community Gardens: Implications for Urban Agriculture

Matteson and Langellotto: URBAN BUMBLE BEE ABUNDANCE Cities and the Environment 2009 Volume 2, Issue 1 Article 5 Bumble Bee Abundance in New York City Community Gardens: Implications for Urban Agriculture Kevin C. Matteson and Gail A. Langellotto Abstract A variety of crops are grown in New York City community gardens. Although the production of many crops benefits from pollination by bees, little is known about bee abundance in urban community gardens or which crops are specifically dependent on bee pollination. In 2005, we compiled a list of crop plants grown within 19 community gardens in New York City and classified these plants according to their dependence on bee pollination. In addition, using mark-recapture methods, we estimated the abundance of a potentially important pollinator within New York City urban gardens, the common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens). This species is currently recognized as a valuable commercial pollinator of greenhouse crops. However, wild populations of B. impatiens are abundant throughout its range, including in New York City community gardens, where it is the most abundant native bee species present and where it has been observed visiting a variety of crop flowers. We conservatively counted 25 species of crop plants in 19 surveyed gardens. The literature suggests that 92% of these crops are dependent, to some degree, on bee pollination in order to set fruit or seed. Bombus impatiens workers were observed visiting flowers of 78% of these pollination-dependent crops. Estimates of the number of B. impatiens workers visiting individual gardens during the study period ranged from 3 to 15 bees per 100 m2 of total garden area and 6 to 29 bees per 100 m2 of garden floral area. -

Conserving Missouri's Wild and Managed Pollinators

Conserving Missouri’s Wild and Managed Pollinators At the heart of the pollination issue lies our bounty of foods such as peaches, Go to the bee, thou poet: strawberries, squash and apples. These and other foods requiring pollination have consider her ways and be wise. been staples in the human diet for centuries, and their pollinators have been highly — George Bernard Shaw revered since ancient times. From Egyptian hieroglyphics and Native American cave paintings to Greek mythology and English poetry, bees and butterflies have been a source of fascination and awe for millennia (Figure 1). Yet, over the past century, pollinator numbers have suffered declines. During this time, global development, a booming human population, and industrial agriculture brought about drastic landscape changes. These changes have resulted in greater losses of forage and nesting resources for pollinators than ever before seen. The ecosystem service of pollination, once taken for granted, is now potentially threatened as many pollinator species face declines in Missouri, the United States and many regions around the world. Pollinators are critically important for natural ecosystems and crop production. Through pollination, they perform roles essential to human welfare. Heightened public awareness of their services and of their declines over the past two decades has prompted action, but much remains to be done. This publication introduces issues regarding the conservation of pollinators in Missouri. It explores why pollinators are crucial, what major threats confront them, what conservation steps are being taken, and how you can help. It highlights bees over other pollinators as bees are the most important for both agricultural and natural pollination in Missouri. -

2017 City of York Biodiversity Action Plan

CITY OF YORK Local Biodiversity Action Plan 2017 City of York Local Biodiversity Action Plan - Executive Summary What is biodiversity and why is it important? Biodiversity is the variety of all species of plant and animal life on earth, and the places in which they live. Biodiversity has its own intrinsic value but is also provides us with a wide range of essential goods and services such as such as food, fresh water and clean air, natural flood and climate regulation and pollination of crops, but also less obvious services such as benefits to our health and wellbeing and providing a sense of place. We are experiencing global declines in biodiversity, and the goods and services which it provides are consistently undervalued. Efforts to protect and enhance biodiversity need to be significantly increased. The Biodiversity of the City of York The City of York area is a special place not only for its history, buildings and archaeology but also for its wildlife. York Minister is an 800 year old jewel in the historical crown of the city, but we also have our natural gems as well. York supports species and habitats which are of national, regional and local conservation importance including the endangered Tansy Beetle which until 2014 was known only to occur along stretches of the River Ouse around York and Selby; ancient flood meadows of which c.9-10% of the national resource occurs in York; populations of Otters and Water Voles on the River Ouse, River Foss and their tributaries; the country’s most northerly example of extensive lowland heath at Strensall Common; and internationally important populations of wetland birds in the Lower Derwent Valley. -

Hymenoptera: Colletidae): Emerging Patterns from the Southern End of the World Eduardo A

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2011) ORIGINAL Biogeography and diversification of ARTICLE colletid bees (Hymenoptera: Colletidae): emerging patterns from the southern end of the world Eduardo A. B. Almeida1,2*, Marcio R. Pie3, Sea´n G. Brady4 and Bryan N. Danforth2 1Departamento de Biologia, Faculdade de ABSTRACT Filosofia, Cieˆncias e Letras, Universidade de Aim The evolutionary history of bees is presumed to extend back in time to the Sa˜o Paulo, Ribeira˜o Preto, SP 14040-901, Brazil, 2Department of Entomology, Comstock Early Cretaceous. Among all major clades of bees, Colletidae has been a prime Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, example of an ancient group whose Gondwanan origin probably precedes the USA, 3Departamento de Zoologia, complete break-up of Africa, Antarctica, Australia and South America, because Universidade Federal do Parana´, Curitiba, PR modern lineages of this family occur primarily in southern continents. In this paper, 81531-990, Brazil, 4Department of we aim to study the temporal and spatial diversification of colletid bees to better Entomology, National Museum of Natural understand the processes that have resulted in the present southern disjunctions. History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, Location Southern continents. DC 20560, USA Methods We assembled a dataset comprising four nuclear genes of a broad sample of Colletidae. We used Bayesian inference analyses to estimate the phylogenetic tree topology and divergence times. Biogeographical relationships were investigated using event-based analytical methods: a Bayesian approach to dispersal–vicariance analysis, a likelihood-based dispersal–extinction– cladogenesis model and a Bayesian model. We also used lineage through time analyses to explore the tempo of radiations of Colletidae and their context in the biogeographical history of these bees. -

Bombus Impatiens, Common Eastern Bumblebee

Bombus impatiens, Common Eastern Bumble Bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Christopher J. Fellows, Forest Huval, T.E. Reagan and Chris Carlton Description The common eastern bumble bee, Bombus impatiens, is an important native pollinator found in the eastern United States and southern Canada. Adult bees are covered with short, even hairs across their bodies. They are mostly black with a yellow thorax (middle section) and an additional yellow stripe at the base of the abdomen. As with other social insects, the different forms, or castes, of B. impatiens vary in size. Worker bumble bees measure from 1/3 to 2/3 of an inch in length (8.5-16 mm), while drones measure ½ to ¾ of an inch (12 to 18 mm). Queen bumble bees are the largest members of the three castes, measuring between 1/3 of an inch to 1 inch (17 and 23 mm) in length. Larvae are rarely seen and are enclosed with the nest brood cells for the duration of their A common eastern bumble bee resting on a flower. Note development. They are pale, legless grubs around 1 inch the yellow patch of hairs on the forward portion of the thorax (David Cappaert, Bugwood.org). (25 mm) in length. At least six additional species of bumble bees have been construction. Within the hollow fiber ball, the queen documented in Louisiana, with another two species possibly deposits a lump of nectar-moistened pollen. The queens present but not confirmed. Identifications are mainly based also construct honey pots near the nest entrance using on the patterns of coloration of the body hairs, but these the secretions of her wax glands. -

Creating Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Pollinator Habitat District 2 Demonstration Research Project Summary Updated for Site Visit in April 2019

Creating Economically and Ecologically Sustainable Pollinator Habitat District 2 Demonstration Research Project Summary Updated for Site Visit in April 2019 The PIs are most appreciative for identification assistance provided by: Arian Farid and Alan R. Franck, Director and former Director, resp., University of South Florida Herbarium, Tampa, FL; Edwin Bridges, Botanical and Ecological Consultant; Floyd Griffith, Botanist; and Eugene Wofford, Director, University of Tennessee Herbarium, Knoxville, TN Investigators Rick Johnstone and Robin Haggie (IVM Partners, 501-C-3 non-profit; http://www.ivmpartners.org/); Larry Porter and John Nettles (ret.), District 2 Wildflower Coordinator; Jeff Norcini, FDOT State Wildflower Specialist Cooperator Rick Owen (Imperiled Butterflies of Florida Work Group – North) Objective Evaluate a cost-effective strategy for creating habitat for pollinators/beneficial insects in the ROW beyond the back-slope. Rationale • Will aid FDOT in developing a strategy to create pollinator habitat per the federal BEE Act and FDOT’s Wildflower Program • Will demonstrate that FDOT can simultaneously • Create sustainable pollinator habitat in an economical and ecological manner • Reduce mowing costs • Part of national effort coordinated by IVM Partners, who has • Established or will establish similar projects on roadside or utility ROWS in Alabama, Arkansas, Maryland, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Idaho, Montana, Virginia, West Virginia, and Tennessee; studies previously conducted in Arizona, Delaware, Michigan, and New Jersey • Developed partnerships with US Fish & Wildlife Service, Army Corps of Engineers, US Geological Survey, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Rutgers University, Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Chesapeake Wildlife Heritage, The Navajo Nation, The Wildlife Habitat Council, The Pollinator Partnership, Progressive Solutions, Bayer Crop Sciences, Universities of Maryland, Ohio, West Virginia, and the EPA. -

Nest Site Selection in the European Wool-Carder Bee, Anthidium Manicatum, with Methods for an Emerging Model Species*

Apidologie (2011) 42:181 – 191 Original article c INRA/DIB-AGIB/EDP Sciences, 2010 DOI: 10.1051/apido/2010050 Nest site selection in the European wool-carder bee, Anthidium manicatum, with methods for an emerging model species* Ansel Payne 1,DustinA.Schildroth2,PhilipT.Starks 3 1 Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, NY 10024 New York, USA 2 Department of Psychology, University of New England, ME 04005 Biddeford, USA 3 Department of Biology, Tufts University, MA 02155 Medford, USA Received 6 February 2010 – Revised 11 May 2010 – Accepted 12 May 2010 Abstract – For many organisms, choosing an appropriate nest site is a critical component of reproductive fitness. Here we examine nest site selection in the solitary, resource defense polygynous bee, Anthidium manicatum. Using a wood-framed screen enclosure outfitted with food sources, nesting materials, and bam- boo trap nests, we show that female bees prefer to initiate nests in sites located high above the ground. We also show that nest sites located at higher levels are less likely to contain spiderwebs, suggesting an adaptive explanation for nest site height preferences. We report size differences between this study’s source populations in Boston, Massachusetts and Brooklyn, New York; male bees collected in Boston have smaller mean head widths than males collected in Brooklyn. Finally, we argue that methods for studying captive populations of A. manicatum hold great promise for research into sexual selection, alternative phenotypes, recognition systems, and the evolution of nesting behavior. Megachilidae / introduced species / solitary bee / enclosure methods 1. INTRODUCTION biased sexual size dimorphism unusual among bees (Darwin, 1871; Severinghaus et al., 1981; The European wool-carder bee, Anthidium Shreeves and Field, 2008). -

Bumble Bees Are Essential

Prepared by the Bombus Task Force of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC) Photo Sheila Colla Rusty-patched bumble bee, Bombus affi nis Declining North American Bumble Bees Photo David Inouye Western bumble bee, Bombus occidentalis Bumble Bees Helping Photo James Strange are Pollinators Essential Thrive Franklin bumble bee, Bombus franklini Bumble Bee Facts Photo Leif Richardson Globally, there are about 250 described species Some bumble bee are known to rob fl owers of bumble bees. They are found primarily in the of their nectar. Nectar robbing occurs when temperate zones of North and South America, a bee extracts nectar from a fl ower without and Eurasia. coming into contact with its reproductive Yellow-banded bumble bee, Bumble bees are documented to pollinate parts (i.e. anthers and/or stigma), usually Bombus terricola many important food crops. They are also more by biting a hole at the base of the fl ower. Photo Ron Hemberger effective than honey bees at pollinating crops Bumble bees are effective buzz pollinators grown in greenhouses. of several economically important plants in When most insects are inactive due to cold the family Solanaceae such as tomato, bell temperatures bumble bees are able to fl y by pepper and eggplant. In buzz pollination warming their fl ight muscles by shivering, bees extract pollen from a fl ower by American bumble bee, enabling them to raise their body temperature vibrating against the fl ower’s anthers, Bombus pensylvanicus as necessary for fl ight. making an audible buzzing noise. Instead of starting their own colonies, some Currently, the Common Eastern bumble bee bumble bee species have evolved to take over (Bombus impatiens) is the only species being another species’ colony to rear their young. -

Melissa 6, January 1993

The Melittologist's Newsletter Ronald J. McGinley. Bryon N. Danforth. Maureen J. Mello Deportment of Entomology • Smithsonian Institution. NHB-105 • Washington. DC 20560 NUMBER-6 January, 1993 CONTENTS COLLECTING NEWS COLLECTING NEWS .:....:Repo=.:..:..rt=on~Th.:..:.=ird=-=-PC=A..::.;M:.:...E=xp=ed=it=io:..o..n-------=-1 Report on Third PCAM Expedition Update on NSF Mexican Bee Inventory 4 Robert W. Brooks ..;::.LC~;.,;;;....;;...:...:...;....;...;;;..o,__;_;.c..="-'-'-;.;..;....;;;~.....:.;..;.""""""_,;;...;....________,;. Snow Entomological Museum .:...P.:...roposo.a:...::..;:;..,:=..ed;::....;...P_:;C"'-AM~,;::S,;::u.;...;rvc...;;e.L.y-'-A"'"-rea.:o..=s'------------'-4 University of Kansas Lawrence, KS 66045 Collecting on Guana Island, British Virgin Islands & Puerto Rico 5 The third NSF funded PCAM (Programa Cooperativo so- RESEARCH NEWS bre Ia Apifauna Mexicana) expedition took place from March 23 to April3, 1992. The major goals of this trip were ...:..T.o..:he;::....;...P.:::a::.::ra::.::s;:;;it:..::ic;....;;B::...:e:..:e:....::L=.:e:.:.ia;:;L'{XJd:..::..::..::u;,;;:.s....:::s.:..:.in.:..o~gc::u.:.::/a:o.:n;,;;:.s_____~7 to do springtime collecting in the Chihuahuan Desert and Decline in Bombus terrestris Populations in Turkey 7 Coahuilan Inland Chaparral habitats of northern Mexico. We =:...:::=.:.::....:::..:...==.:.:..:::::..:::.::...:.=.:..:..:=~:....=..~==~..:.:.:.....:..=.:=L-.--=- also did some collecting in coniferous forest (pinyon-juni- NASA Sponsored Solitary Bee Research 8 per), mixed oak-pine forest, and riparian habitats in the Si- ;:...;N:..::.o=tes;.,;;;....;o;,;,n:....:Nc..:.e.::..;st;:.;,i;,:,;n_g....:::b""-y....:.M=-'-e.;;,agil,;;a.;_:;c=h:..:..:ili=d-=B;....;;e....:::e..::.s______.....:::.8 erra Madre Oriental. Hymenoptera Database System Update 9 Participants in this expedition were Ricardo Ayala (Insti- '-'M:.Liss.:..:..:..;;;in..:....:g..;:JB<:..;ee:..::.::.::;.:..,;Pa:::..rt=s=?=::...;:_"'-L..;=c.:.:...c::.....::....::=:..,_----__;:_9 tuto de Biologia, Chamela, Jalisco); John L.